Cyber optimist manifesto: why we have reasons to be optimistic about the future of cybersecurity

Discussing the achievements we as an industry should be proud of, reasons why we are bad at celebrating success, and why there is an urgent need for cyber optimism

It is not a secret that cybersecurity as an industry is struggling with many problems. Security practitioners and CISOs are over-extended and underpaid. Security leaders are being held personally liable for doing their jobs. People are burning out and leaving their full-time roles. The number of breaches continues to go up and security losses are mounting. I can go on and on but I won’t because these problems are well known to anyone who is even a little familiar with the state of our industry.

In this piece, I am not going to be discussing any of these problems. Instead, I will talk about the achievements we as an industry should be proud of, reasons why we are bad at celebrating success, and why there is an urgent need for cyber optimism. Before we begin, let me first acknowledge that suggesting that people in the industry should be more optimistic is the kind of thought that has the potential to explode into something less than constructive on Reddit or X. Despite the risks of that happening, I believe a discourse around this topic is long overdue.

What CISOs really think about AI (and what they're doing about it)

How are security leaders feeling about AI adoption? Tines wanted to know, so they asked them. Now they're sharing their findings in their latest report: CISO perspectives: Separating the reality of AI from the hype.

From increased pressures on teams to concerns around data privacy, the findings show that AI adoption holds challenges – and opportunities – for security teams everywhere.

Get the full report for strategic insights into how leaders are navigating the integration of AI into cybersecurity and future-proofing their organization.

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Everyday reality of security makes us cynical

Wikipedia defines professional deformation (also referred to as job conditioning) as a “tendency to look at things from the point of view of one’s own professional or special expertise, rather than from a broader or humane perspective”. It is because of professional deformation that we often see high school teachers treating their friends and family members like kids, engineers and architects attempting to explain every fact or action with logic, and programmers looking to solve every problem with technology.

The very nature of security predisposes people in the industry to always look for flaws - vulnerabilities, misconfigurations, software bugs, problems with business logic, and anything that can be exploited. At the end of the day, no matter how much effort the security practitioners put in daily into architecting the organization’s defenses, instrumenting detection and response tooling, identifying and addressing misconfigurations, patching vulnerable systems, and the like, something will inevitably get missed, and when it does, the entire contribution of the security team will be judged based on that single miss alone. If the security team can identify the gaps that matter before the attacker, it can prevent breaches and safeguard company data. The challenge is that the effects of job conditioning in security spill over to other areas of life. This is why security practitioners and leaders frequently become cynical about their jobs, careers, the future of security, human nature, and everything in between. When a single issue can set one’s whole career on fire, it’s hard to judge this pessimism that permeates our field.

Security is not the only profession that suffers from pessimism and cynicism. People in other occupations that deal with matters of life or death under pressure - be it doctors, firefighters, nurses, or rescue divers, - all develop some form of cynicism. Take doctors as an example: while on the day-to-day, they do get to help patients overcome impactful challenges, it’s easy to get discouraged when one fails to achieve their goals daily, and when problems such as cancer and AIDS seem to persist despite all of our best efforts. Even diseases such as Alzheimer's are not yet curable nor reversible - a fact that is incredibly sad to anyone who has been doing what they can to advance the state of medical research.

20+ achievements we as an industry should be celebrating

Although it’s easy to get pessimistic, the truth is that there are many reasons why we as an industry should be proud of the progress we’ve made to date. Here are some of the examples that illustrate that.

Rise of the CISO role and its growing influence

The CISO role is only 29 years old. The world's first Chief Information Security Officer was Steve Katz (1942 - 2023) who was named to this newly-created role by Citicorp back in 1995. Since day one, the role has been perilous and complex. Citicorp didn't create the position because it realized that technology needs to be secured. Instead, around 1994, there were rumors that Citicorp had been hacked, and no one knew whether it was true or not. It turned out that Citicorp’s systems were indeed compromised and Russian hackers stole more than $10 million from the bank.

Since 1995, the CISO role has evolved as did the industry. It is true that the role has become more complex, but it is also more accepted and understood than it was three decades ago. I am optimistic about the future of the CISO role and how it will continue to evolve in the years to come.

Cybersecurity as a board-level concern

From being a niche interest of a small number of hobbyists, cybersecurity has become a real threat to the business, both from regulatory compliance and business continuity standpoint. As such, security is now an important item on the agenda of board members.

The government now expects that board members of public companies have an understanding of security, and are able to oversee the companies’ risk portfolio. This has led to a growing number of security leaders getting positions at public boards (primarily CISOs with experience in Fortune 1000), and a rise of educational programs aimed at upskilling the existing board members on cybersecurity. As an example, the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD), a community of more than 24,000 board members, now offers a CERT Certificate in Cybersecurity Oversight and cyber risk reporting services.

Establishment of the trusted networks for information sharing and collaboration

One of the most impactful developments in security we have seen over the past few decades is the emergence of trusted networks for information sharing and collaboration. Two of the most important ones are Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs) and peer networks.

As the National Council of ISACs explains, “Information Sharing and Analysis Centers help critical infrastructure owners and operators protect their facilities, personnel, and customers from cyber and physical security threats and other hazards. ISACs collect, analyze, and disseminate actionable threat information to their members and provide members with tools to mitigate risks and enhance resiliency. ISACs reach deep into their sectors, communicating critical information far and wide and maintaining sector-wide situational awareness”. ISACs solve the problem of trust when it comes to threat intelligence sharing and collaboration. Historically, security leaders sworn to secrecy and bound by non-disclosure obligations had no incentives to share their most sensitive findings. There was always a danger that their attempt to be helpful would backfire and expose them to personal and professional liability. Since ISACs are supported by the government, they make it possible for CISOs to open up with their trusted peers in ways they are not able to do anywhere else. The Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center (FS-ISAC), founded in 1999, has long been an example of what success can look like, and there are now tens of ISACs active in other segments.

Many other forms of collaboration take part in peer networks for CISOs and security practitioners. Usually, these are invite-only communities that congregate in Slack, WhatsApp, Discord, or on proprietary platforms and encourage professional collaboration. While these communities are invisible and inaccessible to outsiders, they play an important role in the dissemination of best practices, peer support, aggregation of feedback about vendors, professional development, and more.

Rise of professional conferences focused on defense

Since cybersecurity emerged and evolved in communities of hackers, it is not surprising that early security events and community gatherings such as DEFCON have historically been focused on offense, covering areas such as vulnerability exploitation.

As the industry evolved, so did the nature of cybersecurity events. There is now a growing number of high-quality conferences focused on cyber defense. From Blue Team Con to BSides, security practitioners all over the world who are focused on blue and purple teaming, now have many more places where they can connect with peers and exchange learnings. Another sign of the maturation of security as a profession is a growing specialization of security practitioners, and with that, a rise of events for application security engineers (LocoMocoSec), detection engineers (DEATHCon), researchers (LABScon), and others. Black Hat and DEF CON continue to outgrow their venues year after year, making it a yet another sign that the number of people interested in security continues to increase.

Cybersecurity’s movement towards more diversity and inclusion

Two weeks ago, I spoke at the Black Hat Investors and Innovators Summit. One of the sessions titled “Building Trust with CISOs: Key Insights for Startups” was moderated by Christina Cacioppo, CEO of Vanta. It featured two security leaders: John “Four” Flynn, Vice President of Security at Google Deepmind, and Fredrick Lee, a CISO at Reddit. As the participants themselves pointed out, some two decades ago, it would have still been inconceivable to have a session at one of the largest industry events moderated by a female founder and with a black CISO on a panel. All the sessions I attended featured a diverse audience - women, people of color, immigrants, veterans, and so on; not because they are “diverse”, but because they had valuable perspectives to share.

I am not going to claim that we have solved all problems around diversity and inclusion - far from it. That said, I think it’s important that we celebrate the huge success that has been made. We have a large number of conferences and communities with the sole goal of championing diversity. The list includes The Diana Initiative, Women in CyberSecurity, Black Girls in Cyber, Queercon, Blacks In Cybersecurity, Cyversity, VetSec, Vets in Cyber, Sober in Cyber, and others, and all this is not considering one-off events about related problems. Pessimists might argue that the very fact that we have these events, communities, and discussions shows that the problems persist. They would not be wrong, but it’s irresponsible, in my opinion, to not recognize how far we’ve come. In 2024, we have people from all backgrounds in the industry which was far less inclusive and welcoming just a decade or two ago.

Growing number of educational programs

Today, if one is looking to learn security, they are fortunate to have access to all kinds of different resources. From free online tools and resource libraries to cohort-based courses, bootcamps, certifications, diplomas, and degree programs, there is something for everyone. In addition, there is a large number of capture the flag (CTF) competitions where people can be hands-on and even pay-what-you-can training by some of the industry’s best.

There are plenty of options when it comes to educational programs, and while some are better (and more affordable) than others, the point is that security knowledge is freely available, and one doesn’t need to be a part of any special community to get access to it. Pessimists might argue that access to knowledge is not all we need, and that “gatekeeping” remains a problem that prevents young, passionate talent from entering the industry. While there are systemic problems that make finding a job in security hard, it’s an entirely different discussion.

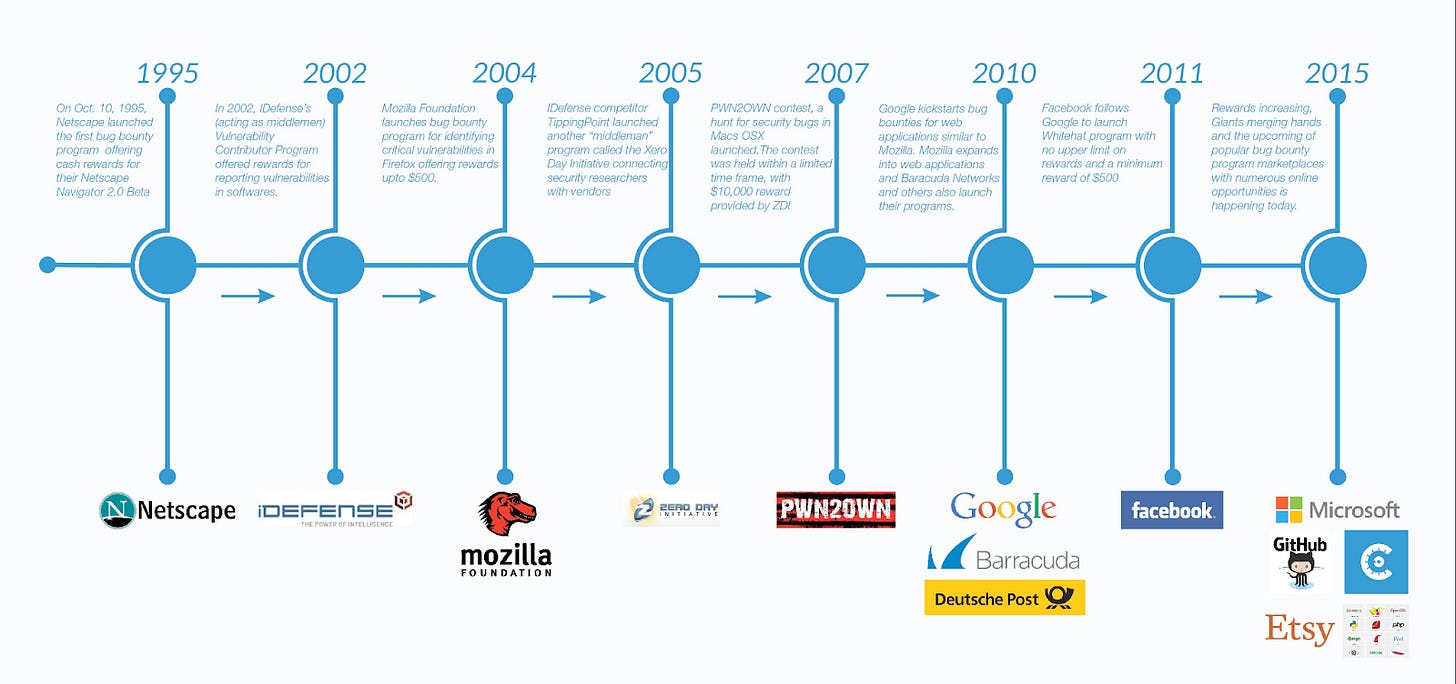

Rise of bug bounties and responsible disclosure

About 14 years ago, Microsoft executives said that the company would “not follow the lead of Mozilla and Google in paying researchers for reporting vulnerabilities”. Less than a decade and a half later, not only has Microsoft become a huge supporter of responsible disclosure, but it’s not easy to find a large company that would not be willing to participate in a bug bounty program.

It has not always been that way. The very first bug bounty program was launched by Netscape on October 10th, 1995. It has taken nearly a decade for Mozilla to follow the suite, and then another five years for Google to join the cohort. Vulnerability researchers used to get prosecuted by the companies they tried to help. It took a lot of hard work from many people - security practitioners, policymakers, industry leaders, lawyers, and startup entrepreneurs to get us where we are today. It would be an overstatement to say that we have solved all problems, but the fact of the matter is that what was once a crime, today is something we take for granted.

For those looking to dive deeper into the history of bug bounties, I highly recommend a brief history of vulnerability disclosure and bug bounty.

Image Source: The History of Bug Bounty Programs by Cobalt

Changing attitudes towards open source software

Cybersecurity always had an interesting relationship with the world of open source. “The nature of open source has changed dramatically over the past two decades. A case in point is Microsoft and its evolution from calling open source “cancer” in 2001, to becoming one of the world’s leading contributors to open source since 2017 (measured by the number of employees actively contributing to open source). A decade ago, most open source projects were driven by individuals with very few companies present in the space, and even fewer being able to generate revenue from their open source offerings (such as OpenNMS). Some projects that started small, over time evolved into large companies with Elastic being a good, prominent example.” - Source: Open source in cybersecurity: a deep dive It’s not like there was no open source in security before; there was, and tools like Nessus which became a foundational building block for what we now know as Tenable, and Snort, which led to the founding of Sourcefire, a company that was acquired by Cisco for $2.7 billion are prime examples.

Today we are seeing a newfound excitement about open source at a completely different scale. Security founders are starting to view open source not just as a tool for side projects but as a business model. More and more security teams of large companies are open sourcing their security tooling - from Facebook’s (now - Meta’s) Osquery and Conceal to Netflix’s Security Monkey, Scumblr, and 10+ other tools, and Cisco’s OpenSOC, projects made public by large corporations have helped shape the current state of security. All this makes security more accessible and open.

Formalization of industry best practices

Over the past several decades, we have accumulated enough knowledge to start formalizing security measures we know to be working into industry best practices. From NIST to HIPAA, CIS and other standards, certifications, and frameworks, we have plenty of sources for both those looking to get started on their security journey, those seeking maturity, and anyone in between.

Skeptics might say that compliance is not the same as security, and they would be right - just because someone checks the box that they do something, doesn’t mean they do what’s appropriate to secure their specific environment. I also previously wrote about the importance of adopting a security-first mindset and why compliance is a bad substitute for security. That said, we have some idea of what works and what doesn’t - much better than, say, two decades ago. And, we have become better at disseminating this knowledge in the form of industry best practices.

Another factor worth calling out is that as an industry, we have become better at testing our assumptions, and being more evidence-based when it comes to evaluating effectiveness of the security measures. For example, it is generally well understood today that forcing regular password expiry lowers security, and that phishing simulations can cause more harm than good. Although we haven’t yet learned to quickly adjust security frameworks and compliance standards when new learnings come in, we are most definitely moving in the right direction.

Security is a priority for the government

Cybersecurity has become a priority for governments all over the world, especially in the US. It’s not just the National Cybersecurity Strategy released back on March 2, 2023, but all the work that has been happening in the background that makes it clear that the government means it. In addition to the contributions of CISA, FBI, and other organizations, the US Securities and Exchange Commission has been raising expectations and increasing its oversight of publicly traded companies and their security efforts. It’s especially refreshing that cybersecurity is a non-partisan issue, and both Republican and Democrat leaders are in agreement about its importance.

International collaboration

In the past several years, we have started to see examples of incredibly effective international collaboration to bring down cybercrime gangs and ransomware groups. FBI, Interpol, the UK National Crime Agency, as well as the US Secret Service, along with law enforcement agencies across Canada, Germany, France, Romania, Lithuania, Sweden, Norway, Portugal, Spain, and Ireland, to name a few, have shown that effective cross-border collaboration makes it possible to go after bad actors. Just a few weeks ago, another international investigation led to the shutdown of the ransomware group “Radar/Dispossessor”.

A decade or so ago, it would have been hard to imagine that this kind of effective collaboration would become possible. Today, it is becoming clear that if we continue moving in this direction, attackers will find it harder to hide and evade responsibility for their actions.

Image Source: Reuters

Image Source: National Crime Agency

Solving problems that caused issues before

Although the internet wasn’t designed with security in mind, we’ve made a lot of progress when it comes to upgrading its building blocks and often completely replacing them with more secure equivalents. Given the security vulnerabilities associated with SSL 2.0 and 3.0, we have largely moved away from SSL in favor of TLS. We’ve moved away from FTP (File Transfer Protocol) to SFTP (SSH File Transfer Protocol) or FTPS (FTP Secure), from Telnet to SSH (Secure Shell), from WEP (Wired Equivalent Privacy) to WPA/WPA2/WPA3 (Wi-Fi Protected Access), from HTTP to HTTPS, and this list can go on and on.

Many kinds of vulnerabilities that used to cause pain a decade or two ago are now forgotten as something we don’t really have to worry about. Naturally, there are plenty of challenges that remain, but it’s worth acknowledging the progress that has been made.

Avoiding the frequently predicted cybermageddon

We cannot forget that the world is much more connected now than it was a decade or two ago. This surely means that there are more issues we need to solve, but it also means that millions (and billions) more people can now take advantage of the good things brought by this connectivity. For example,

It is true that there are more vulnerabilities in code than ever before, but that’s because we ship much more code today than we did a decade ago (which is a good thing).

It is true that there are more IoT devices to secure, but that’s because there are many more IoT devices that improve the quality of our lives today (which is a good thing).

Despite the ever-growing amount and complexity of the infrastructure we have to secure, we have so far been doing quite well. First and foremost, we have avoided the frequently predicted cybermageddon when the whole nation or critical infrastructure segment would go completely dark, causing chaos and widespread disruption and chaos. Second, despite what some media suggest, there are very, very few companies that have gone out of business because of a security incident. Third, most individuals have not yet faced (or even met people) who were impacted by a security incident in a life-altering way. The same cannot be said about cancer or other deadly diseases. Some might argue that it’s a low bar but I think given the amount of money and effort bad actors put into achieving their goals, it’s not an unreasonable way of looking at things.

Security is being built into everyday life

Although we may not yet be secure by demand or by design, we are moving in the right direction. More and more security is being built into the products by default. For consumers, this means that more banks, social media platforms, and other sites now require MFA, while ecosystem players such as Google and Apple are building security into their solutions, from password managers and suggested strong password combinations, to authenticator apps and biometric authentification. For enterprises, this means that more SaaS vendors are starting to support single sign-on (SSO), more granular control over permissions, and so on. While this doesn’t solve all the problems, it is raising the bar of security maturity for both businesses and consumers.

Growth of security as a market

People in the industry like to say that there are “too many security vendors”. Having worked in fintech, a market with over 30,000 startups, and having witnessed other areas of tech such as marketing (over 20,000 companies), HR tech (also over 20,000 companies), and climate tech (over 50,000 startups), I beg to differ. If security is as we like to say "everyone's problem", I don’t think that some 5,000 security vendors are a lot. The world is a competitive space, and security simply cannot bypass this reality.

I have previously discussed why we need more startups and venture capital in cybersecurity. The short version is that:

We need to innovate as fast as the adversaries and the only way to do it is to design a system where people on the defense are incentivized to move fast and iterate on ways to secure our infrastructure often.

We need to educate the market about new problem areas, and people learn those by being exposed to new ideas and startup offerings.

We need to speed up the adoption of best practices such as MFA, and having companies educate customers is how it’s generally done.

Startups act as research and development (R&D) centers for accumulating, refining, and distributing domain knowledge, and that is not possible without capital.

Since there are many ideas and approaches, and whoever tries something first doesn’t always come up with the best way of doing things, competition creates incentives for the best player to win.

Large companies struggle to innovate. This is true for any industry, but in security, a field where we aren’t just dealing with market forces, but also with adverarial behavior, it’s even more critical than in other sectors.

Despite what skeptics are saying, the fact that the cybersecurity market is growing is great news. This is because, among other things,

It shows that companies are paying more attention to security and are willing to spend money on it.

It leads to more capital being allocated to educate the business about the importance of security.

It leads to more power to lobby for regulations that raise the bar for attackers and help companies to become more secure (and yes, buy more products - but that’s a reasonable trade-off in my opinion).

Rise of security engineering

There have been many discussions on Venture in Security about how software engineering principles, systems, and processes are transforming cybersecurity as we know it. Rather than repeating what was said, here are the links I’d recommend to folks interested in this topic:

The rise of security engineering and how it is changing the cybersecurity of tomorrow

Bringing software engineering principles, systems, and processes to cybersecurity

There are many more reasons to be optimistic about the future of cybersecurity

This is just a short list of reasons to be optimistic about the future of cybersecurity. There are many more, for example:

Security products are becoming more user-friendly, interoperable, and API-first. It’s becoming much easier to integrate tools from different vendors, and companies are having a hard time when they want to keep customers inside their walled gardens.

Increased speed of software development enabled by the transition from waterfall to agile, as well as the rise of the cloud and SaaS, means that we can now fix critical vulnerabilities much faster. Instead of having to wait a year until a new release, patches can be applied to millions of customers in a matter of seconds.

There is much more transparency about handling user data, and customers are starting to gain more control over their data. Laws such as GDPR have made it easier for people to demand that their data be treated in ways that are more consistent with their preferences.

Security is becoming much more accessible to those outside of the industry. We are learning to explain problems and concepts without the use of acronyms and industry jargon. It’s taking time to do it better, but we have no choice since security leaders are now expected to communicate risk to other business executives that do not understand our industry jargon.

Security practitioners are starting to develop a stronger voice in the industry. More and more security leaders are starting to empower people on their teams to make decisions, from owning the evaluation of new solutions to recommending which areas of security the company should be tackling next.

There is a growing discourse around the importance of mental health in cybersecurity. As an industry, we’ve made fantastic progress fighting stigmas around mental health, neurodiversity, imposter syndrome, and similar.

The main message is that while there is a lot of work to be done, we are getting better, much better, and it’s happening faster than many realize.

An urgent need for cyber optimism despite all the unsolved problems

It’s too easy to become cynical about the state of cybersecurity. Every day, we hear about the ever-growing number of security incidents, ransomware, and so on. Security conferences such as DEFCON show that everything is insecure, and the number of zero days as well as the amount of money nation-states spend on offence, make us feel that no matter what we do, we’ll lose the battle anyway. Security vendors have reasons to amplify this doom and gloom because it helps them to sell more products. Even CISOs, if they choose to go down that path, can use fear, uncertainty, and doubt to advocate for increased security budgets. It feels like everyone in the industry could be benefiting from all the negativity, which feeds into the never-ending cycle of impending doom.

The truth is, things aren’t that bad. When we look back at the past few decades of our industry’s history, it becomes clear that there is a lot we should be celebrating, and that we have plenty of reasons to be optimistic about the future of cybersecurity.

We need cyber optimists. I get that it’s easier for those of us who are on the vendor side to be optimistic about the future of security than it is for CISOs or security practitioners who are going through incidents as I write this article. I understand it’s hard to be optimistic when people are drowning in what looks like a never-ending amount of bureaucracy. While that is true, I think we should at the very least be willing to acknowledge how much we as an industry have achieved in some three or four decades, without any support and anyone to ask for help. If we were able to do all that, it can only get better from here. We are standing on the shoulders of giants, and we owe them some level of optimism about the future of the industry.