The business of protecting individuals: realities of consumer-focused security, why we cannot expect that people will buy security tools, and what we need to do instead

Looking at the reality of consumer-focused security, why people don’t pay attention to security, which types of B2C security products have seen adoption and which didn’t, and what the future holds

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Over 1,750 copies of my best selling book “Cyber for Builders: The Essential Guide to Building a Cybersecurity Startup” have been delivered by Amazon so far. This book is unique as it talks about building cybersecurity startups. It is intended for current and aspiring cybersecurity startup founders, security practitioners, marketing and sales teams, product managers, investors, software developers, industry analysts, and others who are building the future of cybersecurity or interested in learning how to do it.

Every once in a while I get into a discussion about consumer-focused cybersecurity, and every time it happens, the conclusion is the same: building a business-to-consumer (B2C) security company is not a great idea. To many security practitioners, the mere thought that individuals are not interested in protecting their data doesn’t make any sense. It is easy to think that everyone should understand the importance of privacy and security, and driven by that understanding, take measures to develop the right habits. Guided by this, I must say, quite a logical assumption, the security industry turned to companies promising to increase awareness only to realize that awareness alone isn’t enough.

In this piece, I am looking at the reality of consumer-focused security, why people don’t pay attention to security, which types of B2C security products have seen adoption and which didn’t, and what the future of consumer-focused security looks like.

Reasons why historically, consumers haven’t been paying attention to security

People are quite bad at estimating and understanding risks

There has been a lot of research that explains why humans are notoriously bad at estimating and making sense of risks. We like to think of ourselves as rational actors who make decisions based on factual information, while in reality, we rely on mental shortcuts called heuristics, and are affected by different types of cognitive biases such as availability, survivorship, and halo effect bias.

An infographic by the American National Safety Council does a great job illustrating that Americans often worry about the wrong things. For example, it highlights that:

The odds of dying when riding a car are substantially higher (1 in 470) compared to the odds of dying from a lightning strike (1 in 164,968).

The odds of being killed unintentionally are substantially higher (1 in 31) compared to the odds of being assaulted with a firearm (1 in 358).

The odds of being killed while walking down or crossing the street are substantially higher (1 in 704) compared to the odds of being stung by a bee, hornet, or wasp (1 in 55,764).

Source: American National Safety Council

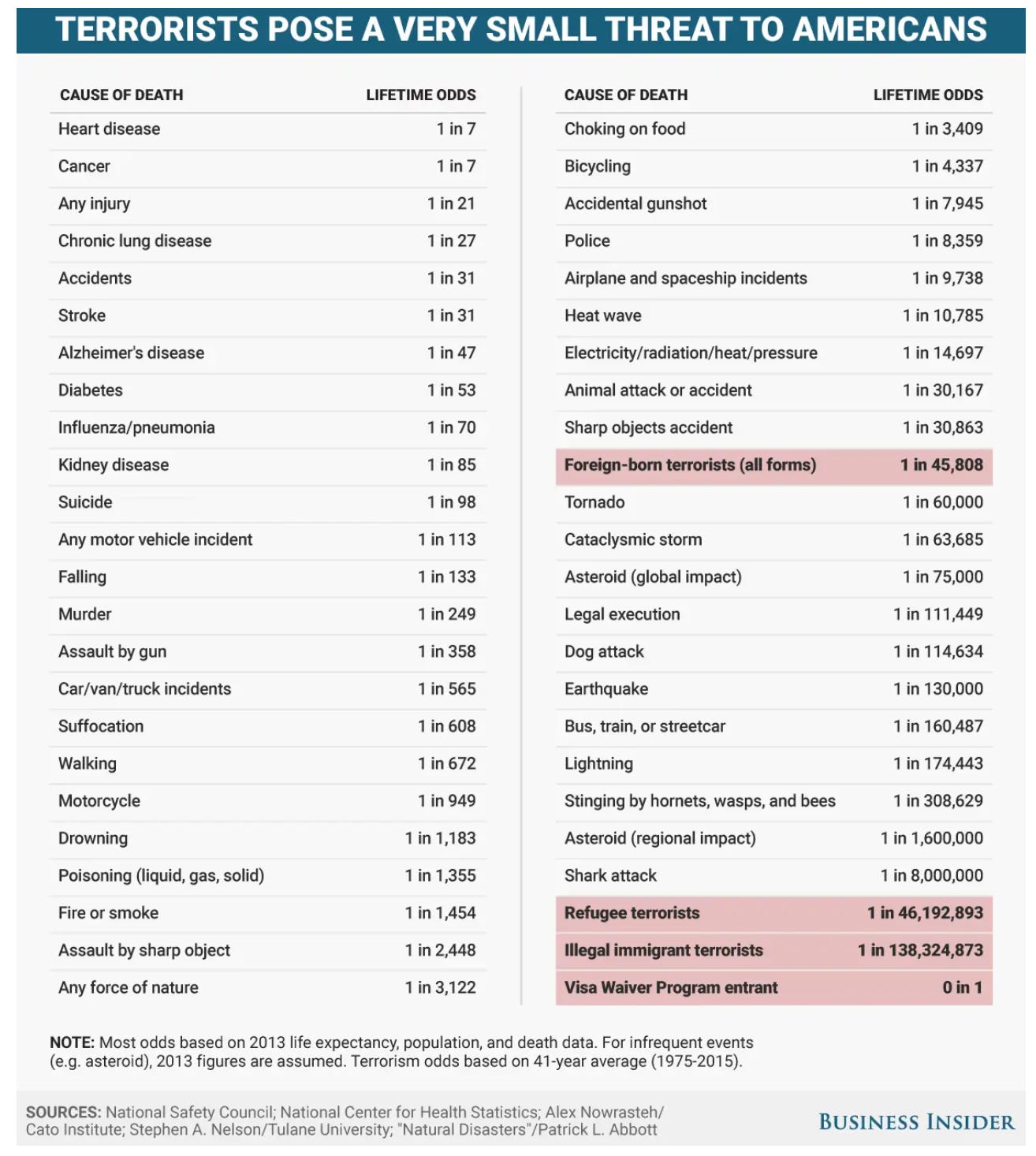

Here is another great source that illustrates that Americans should be more scared of eating sugar and living sedentary lifestyles, than the threat of terrorism.

Source: Business Insider

The world is oversaturated with pleas for help and most people don’t get to hear about cybersecurity incidents

Every day security practitioners get inundated with the number of critical vulnerabilities and security incidents impacting tens of millions of people around the globe. In the Yahoo data breach disclosed in 2017, a group of hackers compromised 3 billion accounts. In 2020, the adult video streaming website CAM4 had its server breached exposing over 10 billion records. In 2021, data of over 700 million (92%) LinkedIn users was posted for sale on the dark web. In 2022, Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba suffered a major data breach that exposed data of 1.1 billion customers. In 2023, more than 3.8 billion records were exposed in the DarkBeam data leak. These are just some of the headlines; we get these every day and at this point, it surely looks like every major company has been breached. Even corporations whose very job is to provide security such as SolarWinds, Kaseya, Okta, and Microsoft, to name a few, have suffered serious security incidents.

Because the vast majority of security practitioners hear about tens of incidents weekly, it feels like the whole world is falling apart. The reality, however, is that people outside of security don’t see even 5% of this news. Social media algorithms and our tight networks make it feel like the news is all over and everyone outside of security just chooses not to see them. Instead, there are many different pockets of passionate changemakers trying to get the world to pay attention to their cause: medical professionals talking about health as a national security problem, climate activists talking about the effects people have on the planet and our own ability to survive climate change, economists explaining why poverty and real estate prices are a national security disaster, innovative educators ringing alarm about the future of young people who are being taught the same subjects, the same ideas, and the same way they grandparent were taught in pre-computer era, and so on.

What looks like a number one issue for us in the industry is just one of many facets of our society and one of many problems that need to be solved.

Most individuals haven’t felt the pain of security incidents

Not only have most people not heard of the major security breaches, but the vast majority of the population haven’t felt any pain when their own data gets leaked. Here are some of the ways in which an average individual gets affected by security- and privacy-related concerns:

Someone gains access to their email address and uses it to send spam. While this definitely creates inconvenience, it doesn’t usually lead to irreparable harm to the victims.

Clicking on some link installs adware on the victim’s computer. In practical terms, this means that once in a while, a person will see some annoying message pop up in the bottom right corner that they will need to close. It’s inconvenient but not deadly.

It is not uncommon for people to have their credit card data compromised which typically leads to fraudulent charges on their bank account. I had that happen several times to me as well; in each of those cases, the bank will typically issue a new card and refund the lost amount.

I am not trying to underestimate the impact of security incidents on people’s lives. There are indeed cases when families lose all the savings it took them decades to accumulate, and private details of one’s lives get leaked causing irreparable harm, and even a loss of life. However, most people think of these stories as anomalies, not something that can affect them personally.

It is hard to blame people for this lack of awareness. Although our data is sold for pennies on the dark web, most people never felt the impact of the Uber or Equifax hacks beyond getting a breach notification email and some free identity monitoring solutions that most don’t understand the value of. The settlements, although deemed as “historic”, haven’t exactly been life-changing from the lenses of individuals.

The absence of security-related education and media coverage

The level of awareness of the importance of security in the mass market is quite low. There are two main reasons why that is the case: the absence of security-related education and media coverage.

Despite the fact that we are surrounded by digital technology no matter where we go, we have not so far prioritized learning how to use it safely and securely. Some countries are moving faster than others. Nearly a decade ago, Israel made cybersecurity an elective in high school matriculation exams. Today, programs such as CyberPatriot, Safe Online Surfing (SOS), and CyberStart America in the US, CyberTitan and CyberStart Canada in Canada, and CyberFirst in the UK, to name a few, are helping to educate young people about cybersecurity. Not-for-profit groups and impact hubs such as Gula Tech Foundation, push for broad social changes, anything from getting more minorities into cybersecurity to educating the general public about the importance of using password managers. Yet, these voluntary programs do not reach everyone and are not enough to make a broad population aware of security and equip them with skills to protect their data. For many years, there have been discussions that we need to start teaching young children about cybersecurity, but not much has been done.

Another entity that has failed to raise awareness of security among the general population is the media. In the case of the media, I think the main reason is the lack of incentives: TV and radio are incentivized to discuss stories their viewers and listeners find captivating so that they continue to watch paid advertisements in between. Most people don’t find cybersecurity an interesting topic: it is about technology which few of them understand, it doesn’t affect their lives (or so they think), and it causes large corporations to lose money - something many individuals in deeply polarized societies aren’t exactly upset about.

To illustrate the degree to which media coverage is misaligned with reality with respect to crime, it’s worth comparing the trend in violent and property crime rates to the trend in cybercrime in the US. As summarized by this chart produced by Pew Research Center based on FBI & BJS data, violent and property crime rates in the US have plunged since the 1990s.

Source: Pew Research Center

On the other hand, identity theft and fraud in the US increased by 300% from 2010 to 2020, according to the data of the Consumer Sentinel Network Annual Reports summarized by Beyond Identity.

The TV and radio networks in the US make it feel like every neighborhood is ridden with danger and crime while cybersecurity incidents are irrelevant. In reality, as we see, the opposite is true. By optimizing for viewership and engagement, media corporations are doing a great disservice to the very people they are serving.

The struggle of building business-to-consumer (B2C) security companies

Selling security products to consumers who don’t understand the importance of security, don’t believe they will be affected by a security incident, and haven't suffered a loss when their most sensitive data has been exposed, is a struggle. The only security solution that gained mainstream adoption among consumers was virtual private networks, or VPN. Ironically, the reason it happened has little to do with security: individuals get VPNs to watch pirated movies and stream films outside of the US, and in some countries, to watch adult content and access sites blocked by the censors. In recent years, there has been a push for the adoption of password managers but it hasn’t been going all that well. Despite all efforts, B2C security startups find that getting enough consumers to adopt security tools is an uphill battle.

Two factors make selling security to consumers especially hard:

People don’t like paying for software. Decades of “free” solutions where companies would monetize customer data by selling it to advertisers or marketing their own products, created a situation where consumers expect software to be provided at no cost.

Security solutions introduce friction, and people dislike friction so much that they will do anything possible to avoid it. Paying money for a tool that makes their lives harder is a tough ask.

Some companies have tried going around these limitations. For instance, the Agency offers security as an employee benefit, removing the need for individuals to pay for the software. BlackCloak, a company securing executives, takes a similar approach. The challenge is that despite the best efforts to make security products “free” for individuals, the fact that they continue to introduce friction makes mainstream adoption a tough task.

Going into the future: recipes for solving the “people problem”

Accepting and embracing human nature as is

Although the business of protecting individuals and getting individuals to help protect businesses look like separate problems, they have common causes: our human nature. There is a long list of cognitive biases we are affected by, coupled with our innate drive to avoid pain and run away from friction, and our inability to understand risk. For decades, cybersecurity discipline focused on solving technical problems, dismissing people as “the weakest link” and assuming that simply forcing them to become more “aware” of security is going to magically change their nature.

This is not going to happen. One of the core reasons adversaries win against security teams is because they understand people, their fears, motivations, and behavioral drivers, and they learn to exploit them to achieve their goals. When people are urged to act quickly, when they are threatened, when they are curious or afraid, they tend to act irrationally. No security awareness is going to change that.

The first step for us to design a more secure future is to embrace human nature and design security for it, not against it. First and foremost, this means designing security measures with a full understanding that people will always look for the easiest way to accomplish their goals. It also means accepting the fact that we cannot expect consumers to buy separate security tools - we need to build security into the current infrastructure and make it a default (and the only) option.

Securing people: future of consumer-focused security

Placing the responsibility for securing individuals on technology providers

I treat the work of founders who dare to tackle the security problems of consumers in an industry where most startups only think about the needs of large enterprises with great respect and admiration. That said, I am not bullish on the future of consumer-focused security tools. In my view, it is highly unlikely that consumers are going to start buying security solutions. Instead, the technology used by individuals must be designed with security built-in.

Every tech company is going to be expected to not only protect the data of its customers but to also help its customers not fall prey to attackers. Security cannot be an opt-in feature; it must become a fundamental property of the way we design software products. The bad news is that it will require some investment. The good news is that it doesn’t have to be hard. Here is an example of how Monzo Bank makes it easy for users to verify if the caller who claims to represent Monzo is legitimate. I am hoping that other organizations will follow this idea and maybe even standardize it, offering consumers an easy way to validate the authenticity of callers.

Source: Monzo on LinkedIn

Monobank, a Ukrainian online bank, offers its customers the ability to choose one of three types of CVV/CVC code (Card Verification Value/Code):

Standard CVV/CVC (auto-generated 3-digit code)

Dynamic CVV/CVC (a 3-digit code that changes every hour which makes it more secure for online transactions)

User-defined CVV/CVC (a 3-digit code that can be set in the mobile app)

HubSpot has a concept of “Security Center Score” designed to encourage users to implement best practices for using the product and handling customer data.

These are just some of the examples. The simplest way in which software providers can help their customers secure their data is by requiring everyone to set up multi-factor authentication (MFA). In 2024, MFA should not be optional in any application that holds sensitive or potentially sensitive customer data.

Technology providers have the power to solve many of the most egregious security problems, but sometimes, they choose not to prioritize them. Recently, Paul Raffile, VP of Risk Intelligence at Teneo, sounded an alarm about a crime that has been killing children all over the US - financial sextortion. As Paul explains in his LinkedIn post, it has been surging up 7200% according to NCMEC. What makes this story especially hard to process is that one single product feature could help make this type of crime harder to execute. According to Paul, “Instagram has the power to mitigate a vast majority of sextortion incidents by making one simple privacy change today: Allow users to keep their Followers and Following lists always private and make this the default setting for minors. Currently, the instant an Instagram user accepts a scammer’s follow request, their followers/following lists are exposed to criminals. This privacy change would mitigate a vast majority of sextortion cases. Meta allows Facebook users to keep their Friends list truly private, but it does not afford teens this same privacy setting on Instagram. Why?”.

Critical role of ecosystem players in bringing security to the mass market

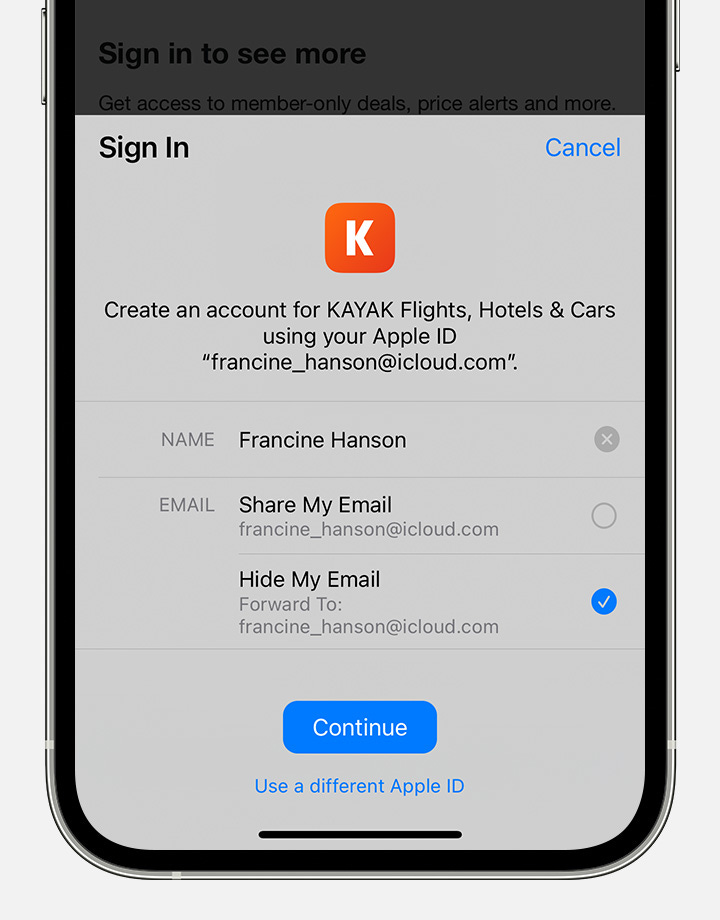

Large technology ecosystem players targeting consumers such as Apple, Microsoft, Google, and Meta, to name some, play a special role in bringing security to the mass market. They are shortcuts in raising the bar for behaviors that promote privacy and security. Instead of having to convince hundreds of millions of users to create a new account with a strong password for every product, they can use “Sign In with Apple”. Instead of having to convince users to buy a password manager, companies like Google can find better and more secure ways to store user passwords than the current in-browser capabilities vulnerable to password stealers and a variety of attack types.

Source: Apple

Many mass-market security innovations will have to come from the ecosystem players because they have the power that early-stage startups don’t. For instance, it has been said many times that passwords the way we know them have to go, and that passwordless authentication is the future. While that may very well be true, it is hard to picture that a small upstart will be able to easily convince the world to adopt a new way of authentication. Companies like Apple, Google, and Meta, on the other hand, with their reach, credibility, and resources, can make it happen much more easily.

The cost of security measures has been and will always be passed onto consumers. However, what’s important is that they are baked into the price of the overall product, and not listed as an optional, opt-in-only line item people have to explicitly agree to pay for.

Moving towards people-centered security

To help people develop the right habits and skills to protect their own data, we must make security accessible. We need to involve people in decision-making and empower them to have a voice when it comes to their security.

The good news is that in many developed countries, we have witnessed what it means to transform an industry where one side has disproportionately more information about their subject than the other, and is seen as an authority in their field. I am talking about healthcare. It hasn’t been too long since doctors were making decisions on behalf of their patients and directing their care the way doctors thought was right for the patients. A few decades later, we have adopted the concept of person-centered care, where the focus is on the whole person, not just the medical conditions.

Here is how Physicians Practice explains the concept of patient-centered care: “Patient-centered care does not mean physicians must give full decision-making autonomy to the patient, just as routine care does not demand that the physician provide full-decision making. It has been shown that many patients who demand certain care, such as antibiotics when not warranted, do respond to proper communication and explanations of why it is not merited. An acknowledgment of their desires is critical, but an informed discussion of why the request is not appropriate should occur. This is actually the definition of patient-centered care - allowing the patient to make an informed decision together with the physician. A respectful, trusting relationship obviously improves this discussion and the patient's willingness to listen to medical evidence and expertise, but even more acute settings where a long-standing relationship has not been established can be successful in these aspects.”

We need to move the industry towards adopting a similar concept of people-centered security. Security is something that needs to happen with individuals, not to individuals.

Investing in security education and consumer awareness

Security education alone is not going to solve all security problems but we need to do more, not less of it. We need to start by teaching the basics of digital safety, privacy protection, and security to those who are most vulnerable - children, the elderly, and people who have a higher probability of becoming victims of cybercrime. This means introducing courses in schools and making them mandatory for everyone to attend. The focus shouldn’t be on promoting security as a profession and going as deep as possible (although these are also important!), but on providing kids with skills and abilities to protect themselves and their data online. This also means teaching the essentials of digital safety in community centers, libraries, and government institutions.

A part of what we as an industry will need to do is fight misconceptions about security and pseudo-security solutions and decide when having something is better than having nothing. Similar to how the internet is ridden with pseudo-medical advice, it is full of pseudo-security solutions. Is writing passwords in a password book a better idea than reusing the same password for every account? Likely yes, but is this a way of handling passwords we should be promoting? Probably not, yet Amazon returns over 2,000 results for “password book”.

Source: Amazon

Even security practitioners themselves don’t always agree about what measures are a good idea. If, despite all the learnings and research, we are still forcing password reset every several months and insisting on doing phishing simulations, I think we should be less critical of things such as password books.

I anticipate that in the coming years, the level of people’s awareness of cybersecurity is going to increase. The line between the physical and digital world is starting to blur, and cybersecurity incidents are starting to have easy-to-understand real-world consequences. When security events start causing people to lose electricity at home, hospitals to halt surgeries, and air traffic controllers to ground all planes across the country (like this time when it happened for non-security-related reasons), it won’t take long for us to realize that there are real-life consequences of our online behaviors. Although I am not a believer in the so-called cyber armageddon, I do think that we will start seeing more and more effects of cybersecurity incidents spill over into the very physical reality. When it happens, I am hoping we will use it as an opportunity to educate people about digital safety, and not to spread fear, uncertainty, and doubt.

Designing regulations to safeguard consumer data

Last but not least, we need to continue to design regulations that safeguard consumer data. As of right now, a treasure trove of sensitive data about US citizens is concentrated in the hands of a few large players. In an attempt to encourage business growth, the US government has always been hesitant to introduce unnecessary restrictions that could stifle innovation. In other countries, the state of privacy and security of consumer data varies: some have institutions that play a role similar to data brokers and are often equally unregulated, while others have none or the most rudimentary protection measures for the data of their own citizens.

A great example of just how bad things are is the 23andMe debacle where a company that holds sensitive health data of millions of Americans can get acquired by a foreign firm which would pose a significant threat to the US national security. Here is how Will Manidis explained what is happening on X.

Source: Will Manidis

Closing thoughts

To help secure the general population, we need to first and foremost embrace reality, and look to deal with it instead of hoping that we can easily change it.

Since people don’t like friction, stand-alone tools are going to struggle to gain adoption. If they are not “baked into” core products and workflows they are designed to protect, they won’t be frictionless. Moreover, consumers aren’t used to paying for security. Due to the fact that traditional ways to monetize B2C software, such as selling user data to advertisers, are at their core antithetical to the very idea of privacy, we will continue to struggle to make money on B2C security solutions.

While we must certainly do what we can to raise awareness of privacy, security, and digital safety among the general population, we need to be clear that technology providers, especially large ecosystem players, are going to be ultimately responsible for ensuring that people within their ecosystem are safe and secure.

Some time ago we ran a campaign asking people how much they’d pay for an internet security suite for their homes. The results were interesting because out of around 1000 people, 1/3 of them said zero or close to zero, 1/3 said half of what a normal product would cost and the other 1/3 were all over the place with less than 10 % getting close to the prices of the time. Then, we gave the option to all of the respondents to buy the product at their requested price, and from those that open the offer, less than 25 % actually bought it. It was an interesting exercise that supports what you said about people not wanting to pay for security.

Wow, this is the best read I had this week.

You identified clearly the frictions that hold people back with security tools.

I will share this. Thank you for your thoughts on this