Let’s get real: there is no such thing as “gatekeeping” in cybersecurity

A deep dive into the problem of so-called "gatekeeping, that explains what actually is happening in the industry, why it is happening, and where we should go from here.

Almost every week I hear someone complain about the so-called “gatekeeping” in cybersecurity. Most discussions about this topic make it painfully clear that very few people in the industry understand the bigger picture, what is happening, and why. Instead of looking at the core of the problem, thousands of people misuse their time by taking sides and defending their position on social media. Some influencers are screaming that young people are intentionally and maliciously denied the chance to get their first job (as if CISOs and hiring managers are conspiring to keep them out of the industry), while others go as far as to say that those who can’t get an entry-level job that requires “5+ years of experience” simply lack talent or dedication. In this piece, I won’t take sides in this debate (not in its current form anyway). Instead, I take a close look at what is often referred to as “gatekeeping”, and explain what is actually happening in the industry, why it is happening, and where we should go from here.

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Lastly, over 2,650 copies of my best selling book “Cyber for Builders: The Essential Guide to Building a Cybersecurity Startup” have been distributed to the readers so far.

Why there are so many discussions about “gatekeeping” in cybersecurity

There are two reasons why there are so many discussions about “gatekeeping” in cybersecurity: the mismatch between supply and demand for security talent, and the lack of the business and broader macroeconomic context.

The mismatch between supply and demand for security talent

The main reason we are hearing about “gatekeeping” in cybersecurity is the fact that the number of entry-level security professionals trying to break into the industry greatly outweighs market demand. That, in turn, is caused by a wide variety of independent yet mutually reinforcing factors.

For the past decade, reports about the so-called “cybersecurity talent shortage” have led to a widespread belief that there are millions of unfilled jobs, and subsequently an unprecedented demand for entry-level security practitioners. It is hard to argue that with the rising number of threats, we need more talent in cybersecurity, and we needed that yesterday. The challenge is that market demand isn’t created solely by the certification bodies and bootcamp organizers eager to produce the new generation of practitioners. Neither is it created by our hopes that businesses will start caring about security. For the market to truly demand more people, there also needs to be a willingness of companies to hire more people. While we’ve got plenty of aspiring security practitioners looking for jobs, and a long list of education providers happy to charge them thousands of dollars for training, the idea that there are four, five, or however many million unfilled security jobs certification providers are claiming the market has is a fantasy.

What we have instead is a generation that has been misled. Bootcamps, universities, and social media influencers haven’t been shy about promising six-figure salaries after several months of training or a degree in security. Instead, not only are there no generous salaries, but no companies willing to hire passionate entry-level people eager and willing to work to make the world more secure. It would be great if all we needed to do to address this problem was to identify and shame some “gatekeepers” but as we will soon discuss, the reality is much more complex.

Lack of the business and broader macroeconomic context

As we will see when we dive deeper into the problem, security is not at all unique. Other areas of technology such as engineering, product management, and venture capital, struggle to develop strong talent pipelines. What is different about security is that most security practitioners, unlike people in other disciplines, don’t get any visibility into the broader business and macroeconomic context. Devoid of such context, many have to rely on their assumptions and try to explain what is happening based on what they know.

Unfortunately, since the business side of cybersecurity is not broadly understood, too many assume malicious intent on behalf of CISOs and management to “keep them away” from entering the industry by inventing artificial barriers, creating unreasonable expectations, and so on. Since social media creates a perfect opportunity for people to amplify one another’s opinions, the belief that security suffers from “gatekeeping” has become commonly accepted as a fact. And, once enough people believe that something is true, it becomes a broadly accepted narrative, even if it is false.

There is no “gatekeeping”: understanding the constraints under which security teams operate

Security jobs are both high-risk and high impact

Hiring cybersecurity professionals is hard for a variety of reasons, but there is one that stands out the most: security roles are high risk and high impact.

Due to how overloaded security teams are, there is usually little chance that peers will be able to check one another’s work. Instead, security professionals need to be able to function independently and with little guidance. Doing so requires experience and solid judgment.

When mistakes are made, their impact can be incredibly high. The reality is that while CISOs are frequently being fired after security incidents, I’ve observed that most incidents happen not because of some grand strategic miscalculations but due to failed controls, small missteps, and overlooked misconfigurations. A seemingly insignificant gap left several years prior can become a root cause of security incidents after the people who let it happen are long gone.

What makes matters worse is that feedback loops in security can be incredibly long which means it can take years to figure out how good someone is at their job. While in customer success, user experience design, quality assurance and other roles management can track people’s performance near real-time, in security many decisions that look good today may become a root cause of incidents several years later. Then there is the importance of luck. Similar to how it is hard to tell if the reason a company didn’t get breached is because it has the latest or greatest tooling or due to luck, it’s equally hard to figure out what role a given security practitioner played in safeguarding their organization.

Because of how costly hiring mistakes can be, security leaders are greatly incentivized to hire people who have experience, and expertise, and have proven that their judgment is sound. Conversely, they are disincentivized from hiring junior talent who, due to the lack of prior track record, are seen as riskier and more likely to make mistakes a tenured security pro would not make. While many years of experience is neither a prerequisite nor a guarantee of good judgment, the absence of experience is certainly seen as such.

Security organizations are small and that has serious consequences

Similar to information technology (IT) and human resources (HR), security is a business enablement function. This means that security teams are small by design; they do not scale linearly unlike sales or engineering which are close to revenue. Since security is seen as a cost center, it is very hard for CISOs to get an increase in headcount. Business logic is simple: “Since adding more security doesn’t help us make more money, we should be fine if our security is good enough. And, since we didn’t get a massive breach in the past 12 months, that would mean we are already doing great. Why spend more than we need?”.

I’ve observed that it is easier for security leaders to get funding for a few new tools than for one new hire. Even if CISOs are successful in obtaining additional budgets, they are not exactly free to bring on board whoever they want. Security leaders are hired by the business and hence they are expected to make decisions that are best for their company. This usually means hiring someone who has a lot of experience and can get up and running quickly.

Let me be clear: from a business standpoint, this approach makes perfect sense. Companies exist to generate profits, not to upskill the next generation of security professionals (or anyone else for that matter). Security teams are hired to protect the ability of the business to generate and keep these profits. Subsequently, leadership expects that CISOs will recruit those who are best positioned to protect the company at the lowest cost.

To make the situation worse, security teams lack the systems and processes required to set up junior folks for success. Because security teams are small, they are constantly overwhelmed with work, and there is rarely anybody with extra capacity to train new entrants to the industry. Once again, that’s not unique to security. That’s also why startups cannot afford to hire junior developers: unlike large companies that have systems in place to absorb and guide new talent, startups need to move fast with the few resources they have. There is no one to train junior engineers and no systems and processes to make them successful.

Another thing worth discussing is the compensation levels often offered to people with many years of experience, as well as job postings that require 5-10 years of experience for entry-level roles. I think those who call out the ridiculousness of these job postings online have all the right to do so (and they absolutely should do it!). But, it’s also important to understand why this is happening. Because security is seen as a cost center, CISOs are frequently struggling to get a budget for expanding the team, and when they succeed, that budget is rarely sufficient. Security leaders aren’t delusional: they know quite well that it’s hard to get senior-level talent for the amount of money their company is willing to pay. On the other hand, they also know that they have no infrastructure to hire someone junior. Their decision is often to shoot for the stars with whatever resources they have - and try getting someone with experience for the little money they have in the budget. Notably, all this has nothing to do with “gatekeeping” or unwillingness to consider people from diverse backgrounds. All these are the second and third-degree consequences of a much bigger problem.

One Reddit user summed it all up incredibly well.

Source: Code-07 on Reddit

Security jobs have prerequisite knowledge

Security jobs require people to have prerequisite knowledge. To put it simply, it is hard to secure something if one doesn’t understand in depth how the thing they are trying to secure works at the fundamental level.

Various security practitioners have different views of what that prerequisite knowledge may be. What is seen as “fundamental” usually depends on the person’s background and where they are in their career. Those already in the industry say that entry-level and aspiring security practitioners should know the fundamentals of everything from identity and access management, cloud security, networking, software engineering, security governance, operational technology (OT), internet of things (IoT), disaster recovery, physical security, procurement, business, personnel and policy, budgeting, and so on. Those looking to break into security, on the other hand, often see these requirements as “gatekeeping” and argue that skills are transferable, non-traditional backgrounds are worth looking at for potential, and not every required skill to perform in cyber needs to be acquired to qualify for the job on day one.

I think both arguments have merits. What is missing in all these debates is the “Why” behind all these requirements.

The reason why security leaders aren’t open to hiring entry-level talent comes down once again to risk. What is the risk of having a person without a background in software engineering trying to secure code? Very high. Can their judgment be trusted? That depends, but if an application security engineer can’t write code themselves and all they are doing is grabbing findings from some tool and sending them over to software engineers to fix, they aren’t adding much value. Or, what are the chances that a person with no experience working in IT can be immediately effective in understanding how to secure the workforce without negatively impacting their productivity? I think it's relatively low.

Entry-level security jobs do need foundational knowledge, but not as a laundry list of requirements but instead as an understanding of what people are trying to protect. For application security that’s code. For cloud security it’s cloud configuration and deployment. For network security, it’s networking and firewalls. For identity security, it’s identity and access management. The list goes on. Without these fundamental skills, we get practitioners who learned to operate tools and click buttons without truly understanding what it is they are doing and why it matters. Moreover, while knowing in depth the areas of security one is going to work with the most is critical, it is equally important to have an understanding of how often industry segments work and how all this fits together. That’s a big ask but there is simply no way around it.

At the same time, there is certainly plenty of room for people from different backgrounds to contribute and find their niche in security,

Security is not unique: broken talent pipeline in other areas of business and technology

Cybersecurity is not unique. There are many other areas in business and technology where it has become, or has always been hard to find entry-level roles.

Product management

While programmers can focus on programming, data analysts on data analysis, designers on design, and attorneys on law, product managers have to possess a broad range of skills from software engineering to design, data analytics, law, compliance, and economics, to name some. Moreover, although product managers (similar to security practitioners) can work in any industry and move from one market to another, having a specific domain expertise is incredibly important. One doesn’t need to know how to, say, underwrite a mortgage in order for them to lead product in a mortgage technology company, or secure its environment. However, having an in-depth understanding of the domain can help product leaders ensure that they focus on the right product requirements, and the same can enable security practitioners to anticipate where people can be trying to exploit their organization or commit fraud.

There are many similarities between product management and security. Both roles are incredibly high risk and high impact, so in both cases, companies are simply unwilling to take chances. In product, it’s extremely important to hire people who know what they are doing as it is hard to tell the difference between a good PM and a bad PM until it’s too late. Feedback loops in product are as long as they are in security. BlackBerry had many well-paid product managers who made decisions that were seemingly good until they didn’t; so did Blockbuster and many other companies the names of which are now used as cautionary tales. In addition, similar to security, product teams are incredibly small (there can be one PM for every 10-20 engineers).

In order to get hired, product managers are required to possess a wide variety of skills and be deep in areas such as business strategy, software engineering, design, data analytics, marketing, and sales, to name a few. Regardless of where one started their career, they will be expected to be proficient in all other areas. This is a lot to ask, but that’s how it works. The expectations are incredibly high - as high and arguably unreasonable as those for security practitioners.

All these factors make it nearly impossible to get a product menagement job without previously accumulating several years of experience, and often building a lifelong career in disciplines such as software engineering, design, customer success, or a specific domain. Even that is not enough because the number of PM roles is much lower than the number of people trying to break into the product. There are some cases when business graduates can do internships at large companies and land a Jr. PM role after that, but in the grand scheme of things it is not as common. “Breaking” into product management is notoriously hard; l know people who had to work towards their goal for several years. Despite this complexity, you will never hear about “gatekeepers” in product - people understand why companies are risk averse and focus on finding ways to get in regardless. I still remember reading books like “Cracking the PM Interview” many years ago and spending hours networking to get that work in product (it took just over a year before I landed it by the way).

Oh, and it’s worth calling out the sheer number of bootcamps promising a six-figure job after a three-month part-time course, or some online certificate. Needless to say, just like we see it in security, what these schools are actually doing is producing large numbers of disappointed and resentful hopefuls who have little to no chance of landing that dream job.

Venture capital

One field where it is even harder to get a job than in product management is venture capital. While everyone is used to hearing how much VCs influence the direction of technology, relatively few know that it is nearly impossible to “break” into venture capital without relevant experience. Large VC firms have two-year associate tracks for MBA graduates and young, passionate professionals, but 1) there are very few large VCs, and 2) these programs are incredibly selective.

There are a few reasons why VC is such a competitive area. The main one is the mismatch between supply and demand for talent. There are tens or even hundreds of thousands of people who dream to become investors and help pick the next Google or Meta. At the same time, there are only a few thousand VC firms. What makes the whole situation worse is that most VC firms are fairly lean: while a few like a16z and Sequoia have several hundred people each, the vast majority are teams of 1-20 people. This is because VC firms only get 2% of the fund size to cover their expenses. For example, a $25 million fund will have $500,000 per year to pay everyone’s salaries, cover trips and conferences, pay for office rentals, etc. That is also why on one hand, VCs are incentivized to keep their teams small, and on the other hand, they have strong reasons to raise more capital (bigger funds mean more fees).

Feedback loops in venture are the longest since it takes ten or more years to see if one is truly successful at what they are doing. Of course, there are signals people can evaluate along the way but the ultimate criteria - real returns - take decades to materialize. All these and many other factors make the VC space very conservative and risk-averse.

Software engineering

What is probably most surprising is that junior roles in software engineering have also become nearly impossible to get. This hasn’t been the case before, but the market has changed and with that so has the willingness of companies to hire and train new graduates or even more so, people without formal education/degree in engineering.

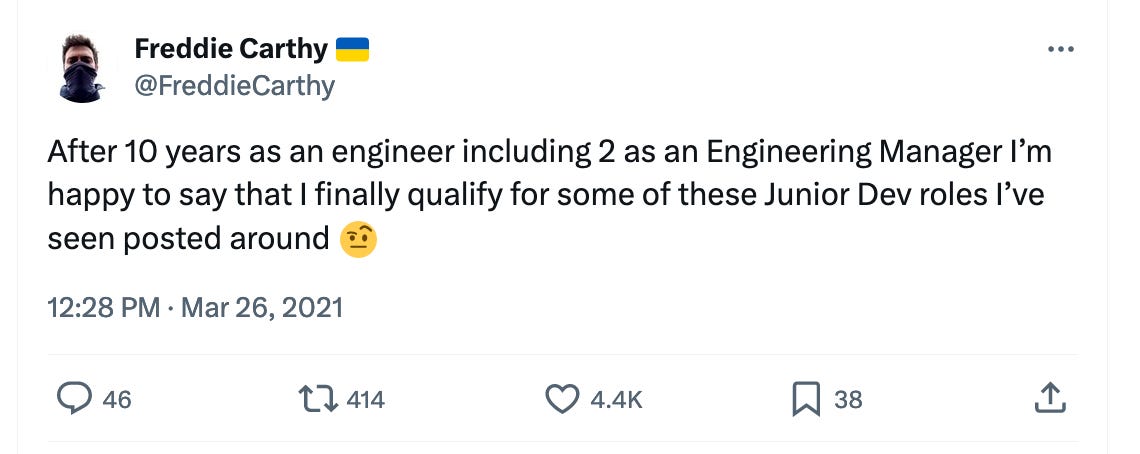

Source: Freddie Carthy on X

When the money was cheap, businesses were willing to hire junior engineers and spend six months to a year helping them become productive contributors. In the world of high interest rates, this is no longer the case and there are barely any companies left who are open to hiring and training entry-level software engineers. If you are interested in learning more about this problem and the reasons why junior software developers are struggling to find jobs, I highly recommend this YouTube video.

The uncertain future of entry-level jobs in cybersecurity

Dealing with the economic realities of the new world

Truth be told, this isn’t just software engineers who have been struggling to find jobs. TrueUp has been tracking the total number of open tech jobs at tech startups, tech unicorns, and public tech companies, and needles to say it is not looking great. There are over 50% fewer jobs in tech than there were at the peak in 2021 - that’s a huge difference.

Source: TrueUp

This begs the question: are security jobs immune from the broader macro-economic impacts? I don’t think so. While security teams may be less affected by the budget cuts because nobody wants to be held responsible for breaches, we won’t certainly be seeing companies hiring junior security practitioners en masse. Security leaders aren’t creating budgets out of thin air - because security is seen as a cost center, every hiring decision of the security team is usually heavily scrutinized. When CISOs are asked to put together a business case for adding a new full-time role, they know that they simply have no time to train someone junior. They need people who can hit the ground running immediately, without requiring any additional resources or support.

This is something few junior security practitioners can fully understand. It looks easy: they studied hard, so they should get an opportunity to contribute. They are right - that’s how it should work, but it is rarely that simple. Security teams need to be ready to onboard and train entry-level security practitioners, and that’s hard to do when they are barely keeping up with the already overwhelming amounts of work.

With money no longer being free, I think it will become even harder for junior talent to get hired, both in cybersecurity and outside of it. Companies are looking to get the highest return on their dollars spent, and hiring experienced professionals is one of the ways to do it. To put it differently, in the era of capital efficiency, businesses are incentivized to run lean, and that in turn requires people who can do their work without extra guidance and additional management layers.

Impact of automation on the security job market

One factor that has many security practitioners worried about the future of their careers is generative AI. And, there are good reasons to be worried.

Generative AI is a form of automation, and automation is not new to security. On the contrary, I would argue that automation is at the core of most security solutions. Think this way: there is no security problem that cannot be solved by people. From triaging and investigating alerts to fixing misconfigurations and notifying the right individuals at the right time, all of this is best done by experienced security practitioners. The problem is that we don’t have an unlimited number of these practitioners, and even if we did, businesses are certainly unwilling to spend the amount of money hiring them would require. Moreover, large volumes of data necessitate the ability to make informed decisions at scale, and humans aren’t that great at this. This is why every security solution is an automation solution.

Bit by bit, we’ve been chipping away at the manual tasks required to secure organizations’ environments. First, we’ve built a bunch of tools that could automate detection. Then, with the help of security orchestration, automation, and response (SOAR) products, we got rid of even more repetitive work with playbooks (although not as much as vendors promised). And yet, despite all our attempts to automate security, we were never great at it: detection tools generated a ton of false positives that all needed to be manually investigated, and SOAR platforms required people to have an overlap of two hard-to-find skills, playbook creation and incident response. Since most companies lack this rare (and expensive) talent combination, the promise of security automation tools has not been fully realized.

Playbooks and security tools notwithstanding, companies have been incentivized to continue hiring a small percentage of junior security practitioners to do some basic (often repetitive) work manually, while they learn the ropes of their craft. Today, with the rise of generative AI, that is no longer true. A large number of startups are starting to automate away the kind of work that was previously done by entry-level professionals. For example, instead of hiring Tier 1 SOC analysts, security teams will soon be able to buy AI agents. It remains to be seen to what degree generative AI will actually be able to fulfill its promise, but it is indeed becoming clear that the world of work has changed forever. ChatGPT isn’t perfect at copywriting but it’s better than many entry-level writers. It’s certainly not great at writing code, but it’s decent at writing simple code for simple use cases, the kinds of use cases that were previously handed over to junior engineers. And, while LLMs are not going to replace security practitioners, they can certainly do the work that junior and aspiring security professionals are doing today.

Poor employee retention

In recent years, as the average number of years people stay at their jobs continues to decrease, companies have fewer incentives to hire new talent, in security and beyond. Since people only stay with their employers for 1.5-2 years, and it can take a full year for junior folks to become productive and start adding value, for companies this equation doesn’t make much sense.

In security in particular, there is a lot of demand for mid- and senior-level talent and very little demand for junior talent. Theoretically, companies would hire people new to the industry and help them grow, thus creating loyal employees. In practice, however, it’s almost inevitable that as soon as security practitioners have a few years of experience under their belts, they will leave for better compensation packages or simply new challenges. Businesses hiring junior talent can therefore find themselves at a disadvantage: they have to pay the price for training new security practitioners only to see them leave a few months after they start performing at the mid or senior level.

The great divide between engineers and operators

I am seeing that the gap between the experience of engineers and operators continues to grow, and nowhere it is more clear than in the job market.

Security engineering, and specifically a combination of software engineering and cybersecurity expertise is in very high demand. Security engineers with a few years of experience have no trouble securing job offers and negotiating sky-high compensation packages. It is as if the overall decline in the number of tech jobs and high interest rates have had zero impact on the market for security engineers. At the same time, finding a job as an operator (think SOC analyst, IT analyst, etc.) is a nightmare. The job market is insanely competitive, salaries are low, and requirements are untenable.

I anticipate that this divide is only going to get worse. There is indeed a great shortage of software engineers with expertise in and passion for cybersecurity. And, there is an oversupply of people trying to break into the industry with no prior experience and few certifications. Both are important, but market fundamentals for both could not be any more different. The way they are hired is different as well. Security engineers are builders, so they are hired similarly to software engineers - by showcasing their engineering skills, portfolios, and so on. With operator roles, there are no portfolios that can be analyzed or reasoned about, so hiring managers resort to evaluating other, more intangible signals like certifications, connections with the industry, transferable skills, etc. This makes it much harder for hiring managers to recognize talent, and for aspiring security practitioners to show what they are capable of doing.

Forging the path ahead: creating opportunities for junior talent to succeed

Learning to recognize the reality of security

This may sound discouraging, but I think that no matter what we do, we won’t be able to change the core problem: security is a cost center, and as such, it will always struggle to get enough resources. Lack of resources will continue to lead to CISOs trying to do the best they can with what they’ve got, and hoping that some unicorns with 10+ years of security experience will apply for jobs paying minimum wage. That isn’t because CISOs are delusional, but because they have no other choice. They have no resources to train new entrants to the industry, and so they have to hire the most senior people they can afford. A side effect of this reality is that those without cybersecurity experience (let alone those coming from different backgrounds) will continue struggling to break into cybersecurity.

Learning from how other professions have been solving the same problem

Complex problems demand systemic solutions. Despite the commonly seen pessimism about the state of security, I think we have done a great job evolving our industry. There were efforts led by people like Chenxi Wang to get rid of “booth babes” at the RSA Conference and Black Hat and guess what, we did that. There was a movement to get vendors to integrate with one another and stop creating walled gardens, and I think we’ve been confidently moving in that direction. Don’t take me wrong - there’s still a ton we as an industry need to do better and a lot of it can indeed be accomplished by educating ourselves about problems, collectively committing to solutions, and calling out the worst offenders on social media. The lack of diversity in security is a good example of such a problem. Unfortunately, the problem of “gatekeeping” isn’t one of them because as we’ve established, it’s not caused by having monsters serving in CISO roles, but by complex business and economic realities. To stop “gatekeeping”, we need to deal with these realities.

This doesn’t mean there is nothing we can do. While we cannot change reality, we can make it better. I think the number one step should be to look at other industries that suffer from similar problems and learn from them. The security community likes to reinvent the wheel and assume that we are solving everything for the first time, but it’s much more productive to look around and borrow what worked in other fields while ignoring what didn’t. The examples below are not exhaustive - they are an inspiration and not a to-do list.

Learning from software engineering

It is anything but easy for software engineers to get their first job. And yet, in many companies, hiring managers have learned to not screen for knowledge of specific languages and frameworks and instead test one’s ability to solve problems.

Unfortunately, cybersecurity has not yet come to the same realization. Most companies are testing one’s memory of different security tools instead of checking if the person is able to analyze and solve complex problems. This is ironic because 1) things change all the time so the ability to learn should matter more than what the person knows now, and 2) attackers are succeeding because they are thinking creatively and we cannot hope to stop them with the mindless operation of security tools. Moreover, tools are just that, tools. We need people who understand security, and it shouldn't matter which specific tool they use at their jobs.

Learning from product management

Despite nearly a two-decade effort to make product managenet more acessible, the problem is still there (but it is not as bad as it was before). That, to a large degree, is due to the rise of associate product management (APM) roles. I think Silicon Valley Product Group popularized this program in the early 2000s and Google was the first to implement it. Now, it is also available at Uber, Salesforce, Atlassian, Shopify, Instacart, Yahoo, Meta, X, and Dropbox among others. The way the APM experience is structured at various companies is different; what doesn’t change is the fact that these programs enable aspiring PMs to gain experience which is critical for finding a subsequent role in product.

Companies that run APM programs have made one thing very clear: shaping entry-level talent requires considerable investment. Not only does running the programs themselves cost money, but it also comes at the expense of productivity for other workers employed full-time who now have to support APMs, find time to mentor them, answer questions, provide context they need to learn (and do) something useful, etc.

It would be unfair to say that only leading tech ecosystems like Silicon Valley have benefited from programs such as APM. The Canadian product management community has shown that impact is possible even when there is a lack of resources. In the Canadian province of Ontario, a group of product leaders recognized that outside of the previously mentioned successful US firms, resources are often too tight to effectively structure APM programs to fully empower and train entrants to the product role. In 2017 a group of product-focused organizations in Toronto got together to fix this problem. Over the years, they’ve run several cohorts of APM Canada, “a collective of product leaders cross-training APMs in which 20 companies have added 40 new entry-level PMs to the Canadian ecosystem. The 6-month APM program runs to augment vocational placements with in-depth training sessions and create an incredible network to prepare APMs to be able to handle any challenge the product world can throw at them.”

The APM Connect program is now run by Product Calgary. As their website explains, “APM Connect is a fully remote, Canada-wide program that pairs structured curriculum learning with hands-on experience for Associate Product Managers (APMs) who are just starting their Product career or have comparable experience and would like to transition into an APM role on your team. It brings this small group of self-driven candidates through a vocational training model.” In other words, APM Connect makes it easier to hire entry-level product people by taking care of their training and helping them to get up and running quickly.

Could we benefit from having a similar program in security? Probably. If CISOs can offload some of the hard parts of onboarding junior security practitioners, they could be more likely to advocate for bringing more of them on board. Given how vast cybersecurity as a discipline is, participants of such a program, if it existed in security, could get exposure to different areas of practice such as networking, cloud security, endpoint security, third-party risk, and so on, before zooming in on the domain they are most interested in. Opportunities are plenty, but someone needs to do this (and pay for it).

Learning from venture capital

Venture capital, as we’ve discussed, is notorious for being a tough industry to break into. And yet, there are some things cybersecurity can learn from the VC space.

Most associate roles in VC are two-to-three years rotational programs where young people passionate about venture are tasked with deal sourcing, community building, and other efforts designed to help them learn about the work of VCs while making it easier for investors to identify and support promising founders. There is no expectation that at the end of these few years, the person will get hired into a permanent role, but this short rotation is more than enough to jumpstart one’s career. VCs aren’t doing this for charitable reasons: they know that young people are resourceful and motivated to work hard to achieve their goals of advancement and professional growth.

Despite the presence of these multi-year rotation models, finding opportunities in VC (or even getting accepted into such a program) is still incredibly hard. This is where initiatives such as Laconia Venture Cooperative and Included VC come in. Vastly different in their nature, they both strive towards the same goal: helping people from diverse backgrounds break into venture. Laconia’s Coop makes investment practices and knowledge of Laconia VC accessible to the broader cohort of fellows. Included VC, co-founded by Notion Capital and supported by a vast network of VCs, provides an very deep, hands-on program about venture after the graduation of which nearly 90% of people actively applying to break into VC successfully did so. Both programs are free to join.

Would we benefit from having something similar in security? Maybe. What if we could get tens of senior security leaders to dedicate their time and effort and help the next generation break into the industry? If we know that the number one obstacle for young people looking for jobs in security is finding that first role, then maybe there could be an opportunity to help them gain experience in some other ways, say via fellowships? Possibly. If we could combine the solution to this problem with, say, an opportunity to help defend small and medium-sized businesses, hospitals, schools, or election campaigns, we could find a way to hit a few birds with one stone.

Closing thoughts

If more and more companies will be exclusively hiring senior talent, how can entry-level security practitioners ever get a job? If there will be no career ladder for junior talent, where will senior talent come from? And, if there will be no “basic” work left for entry-level people to do, what will they be doing? Sure, many would argue that we can now focus on “higher-value” work, but in practice, it’s not as easy to figure out what that “higher-value-entry-level work” is. You are right to think that hiring even fewer entry-level talent would be shortsighted and detrimental to the future of our industry. But, in today’s business world, everyone has the incentives to maximize short-term returns to their own shareholders. When everyone is playing a short-term game, as an industry collectively we end up with yet another tragedy of commons.

Solving hard problems is hard. As with many things in life, there are no shortcuts. Or maybe, we’re not looking in the right places. It’s great to talk about “gatekeeping”. It gets people riled up. It feels like an injustice. It gets likes on social media. The reality is that barriers that prevent entry-level security practitioners from being able to break into the industry are systemic, and dismantling systemic barriers is only possible when we look at them holistically.

My hope is that by better understanding the problem, we can be better equipped to brainstorm potential solutions. As if I haven’t repeated this enough times, CISOs aren’t monsters, job candidates aren’t lazy, and “gatekeeping” isn’t the real problem. By redirecting all that admittedly justified anger from social media to collective problem-solving, I am confident we will have a better chance to build an industry that is willing, ready, and able to give the next generation of practitioners a chance to solve problems waiting to be solved.

Interesting. But it seems like the lack of _gatekeepers_ is the basis for the article to assert that _gatekeeping_ is not happening. I would argue that there is indeed a “gating function” happening with regard to infosec/cybersecurity. Take, for example, women’s representation in the field or in technology in general. Abysmal. You need look no further than the misguided and mysogenistic Palo Alto marketing event at Black Hat to see fresh signs of talent being discouraged and outright excluded from feeling welcome and equal.

faxses. its not a skill issue. its an attrition issue. ive taken a figurative dump in the comments a few of these “skill gap alert!!!” cringe posts https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7191097781808160770?commentUrn=urn%3Ali%3Acomment%3A%28activity%3A7191097781808160770%2C7191237581747978241%29&dashCommentUrn=urn%3Ali%3Afsd_comment%3A%287191237581747978241%2Curn%3Ali%3Aactivity%3A7191097781808160770%29

edit: sorry, im late on this post i just realized.