Most of the security teams’ work has nothing to do with chasing advanced adversaries

Discussing what the day-to-day reality of security teams looks like, and the reasons why we need to build products designed for the real needs of security practitioners

If someone new to the industry were to spend a few hours watching movies about security (pick any of your favorites), or going through the industry marketing, they would inevitably conclude that security teams are warriors who spend 24/7 fighting advanced and highly targeted attacks, patching zero-days to prevent them from being exploited by nation-states, and responding to incredibly sophisticated threats.

On the other hand, if the same person were to attend a local BSides, Blue Team Con, or any other practitioner-focused conference and ask people what their day-to-day looks like, they would be surprised to learn that it’s not all about stopping nation-states and preventing nuclear disasters, and that most of security team’s responsibilities look similar to folks in other departments.

In this piece, I am diving deeper into our habit of glamorizing attackers and defenders, discussing what the day-to-day reality of security teams looks like, and the reasons why we need to build products designed for the real needs of security practitioners.

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Over 2,150 copies of my best selling book “Cyber for Builders: The Essential Guide to Building a Cybersecurity Startup” have been delivered by Amazon so far. This book is unique as it talks about building cybersecurity startups. It is intended for current and aspiring cybersecurity startup founders, security practitioners, marketing and sales teams, product managers, investors, software developers, industry analysts, and others who are building the future of cybersecurity or interested in learning how to do it.

Day-to-day reality of doing security

Although cybersecurity likes to glamorize attackers and defenders, the reality is that an average security team is not spending most of its time detecting and responding to attacks of sophisticated adversaries. A lot of security work is fairly mundane. Someone on the sales team sent sensitive data to a SaaS tool not approved by IT. Someone on the finance team clicked a link and failed a phishing simulation test. Someone on the engineering team created a public S3 bucket. Once in a while, someone from marketing gets phished, and someone from customer support falls for a scam email.

A lot of the security team's time is spent automating manual processes (patching, vulnerability management, etc.) and even more on communication, documentation, and compliance. That said, there are two types of security jobs: those where less than 10% of the time is spent on incident response, and those where it’s all about chasing adversaries over 90% of the time.

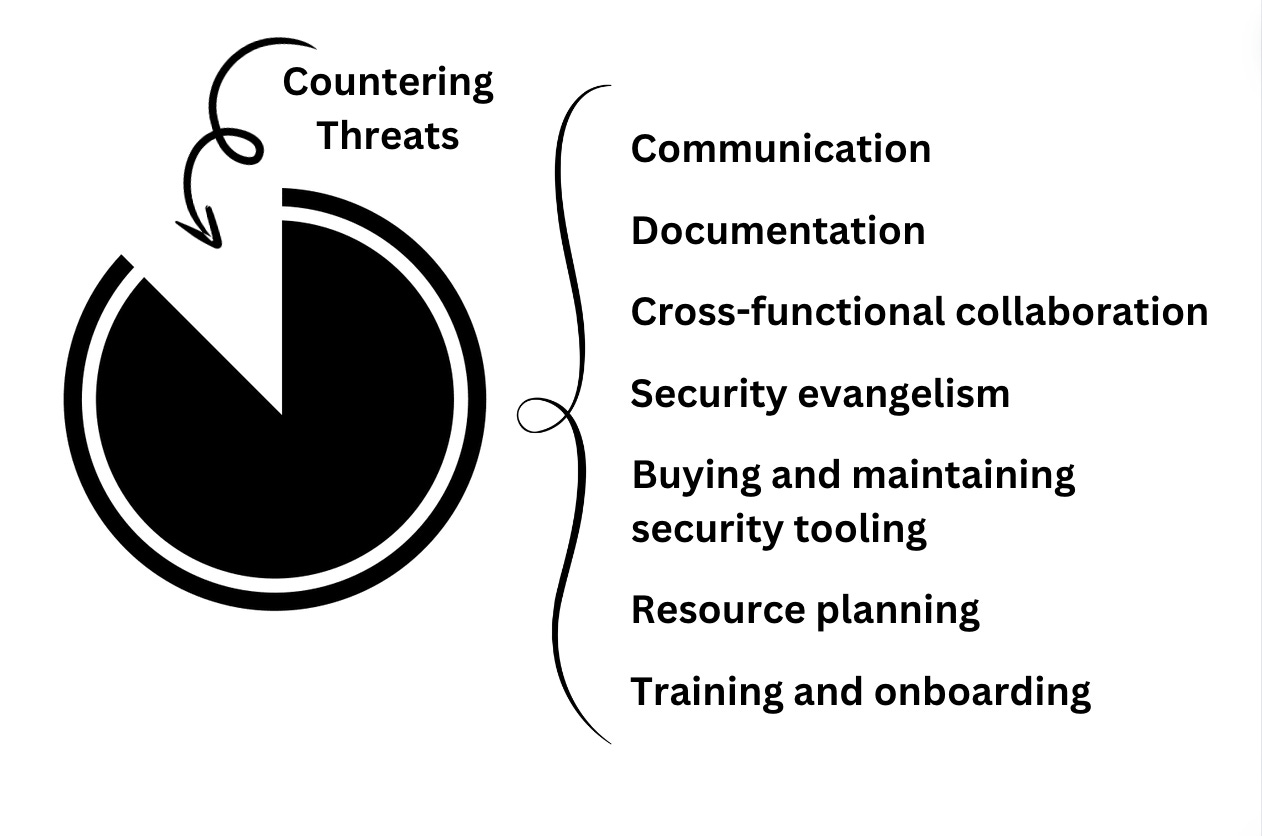

For most jobs, about 90% of daily responsibilities are similar to any other office work

While many people join cybersecurity after being inspired by the idea of hacking, the vast majority of security work is far removed from actively trying to catch adversaries. Working on a cybersecurity team at an enterprise is similar to working on any other team, in that a disproportionately large amount of time is spent on:

Communication, which includes meetings, sending and responding to emails and messages in Slack or Teams, answering questions, preparing reports and status updates, tracking key performance indicators (KPIs), and coordinating with other departments.

Cross-functional collaboration, which includes reading and writing documentation, understanding how different departments do their work, coordinating complex initiatives spanning multiple teams, explaining the importance of various controls to employees and functional leaders, and negotiating the minimum realistic security measures.

Security evangelism, which includes explaining why passwords cannot be saved in the spreadsheet or sent via text (even via encrypted messaging platforms), why service accounts cannot have domain admin rights, why people should use Yubikeys instead of the SMS-based MFA, and the like. Most importantly, all this needs to be done without becoming a bottleneck for people trying to do their work and achieve company revenue goals, and without ruining relationships with everyone at the organization.

Buying and maintaining security tooling, which includes conducting gap analysis, testing new security solutions, periodically assessing the implementation of existing security tools, addressing issues surrounding configuration, and deciding which policies are appropriate to be implemented in what parts of the environment.

Resource planning, which includes negotiating budgets and headcount, justifying investment in specific areas of security, structuring, organizing, and re-organizing teams, and working with human resources and recruiters to develop hiring and employee compensation plans.

Training and onboarding, which includes reading and writing documentation, and guiding new employees to get up to speed with how things are done at the organization.

Many would argue that these things are boring, but such is the nature of office jobs, and work in general - a lot of what we do are mundane tasks that just need to get done and not the most exciting initiatives that use all of our skills and abilities. Every office job has a part that lives in Excel spreadsheets and PowerPoint presentations.

The fact that most of the work in security is mundane is good news. Imagine if security practitioners had to deal with ransomware incidents in their organization daily, or if every security leader had to wake up at 3 am not occasionally, but six days per week?

The minority of jobs where detection and response is a daily reality can get incredibly draining (but even in these jobs, there are some mundane parts)

Although the majority of cybersecurity jobs are akin to any other office job, there are those that are unlike almost anything else in the private sector, namely high-alert incident response and security operations center (SOC) positions. I say “almost” as there are many kinds of high-stress jobs - air traffic control, nursing, emergency response, law enforcement, disaster recovery, and others. That said, there are few office jobs with a level of stress which is comparable to cybersecurity incident response.

Security practitioners who work in incident response, are laser-focused on getting attackers from the network. It’s a high-stress job that often requires people to sacrifice any hopes for work-life balance. That said, even in incident response there is a lot of “office” work that needs to be taken care of, from writing reports to creating, revising, and distributing technical documentation, sending emails, and attending meetings.

The day-to-day in a SOC varies greatly depending on the company, how mature its security practices are, the amount of experience employees bring to the table, and other factors. For some, working in a SOC is akin to working at an IT helpdesk where everything is about closing as many tickets as possible, most of which are trivial and do not require a lot of creativity. For others, it can be about leveraging their experiences in threat hunting, detection engineering, automation, and incident response. Overall, it can get very high stress because humans are expected to triage, investigate, and resolve alerts generated on a machine scale.

Another example of a job that involves a large amount of tedious work is pentesting. While most people think of pentesting as hacking and finding creative ways to bypass an organization’s defenses, a lot of the daily reality is uncovering fairly basic mistakes and writing reports. The latter can be particularly draining: pentesters are expected to document their findings and demonstrate the due diligence they put into testing.

Three reasons why cybersecurity tends to have a lot of overhead and bureaucracy

There are three reasons why in cybersecurity, it’s very hard to run away from bureaucracy and tedious work.

First and foremost, when we talk about cybersecurity, we usually mean the security needs of large enterprises. While I am not suggesting that individuals and small businesses do not have reasons to invest in security, the reality is that it’s large enterprises that constitute most of what we think of as security customers and employers. Coordinating the work at large enterprises involves dealing with thousands of people driven by different incentives, evaluated using different performance metrics, and operating in different business contexts. Since security teams interface with all other parts of the organization, it’s no surprise that Excel spreadsheets, meetings, documentation, and processes and procedures are a daily reality of their work.

Image Source: Four cybersecurity startup dilemmas and what they mean for security founders and the industry in general

Second, industries with the highest amount of bureaucracy tend to also be subject to the most stringent regulatory requirements, and therefore be seen as the largest buyers of security. Whether we are talking about healthcare, finance, critical infrastructure providers, or the government, organizations in these sectors are by their very nature highly regulated, and as a result, slow-moving and averse to changes.

Last but not least is compliance. Although we like to think about security as a necessity driven by the attackers, for the majority of businesses the main driver for their buying decisions is compliance with various regulations. Checking boxes and ensuring that different requirements are met is a big part of what security is intended to accomplish, hence why it is not surprising that managing Excel spreadsheets and keeping up-to-date documentation are important components of security practitioners’ day-to-day responsibilities.

Cybersecurity products, over-optimized for fighting advanced adversaries, are failing the day-to-day needs of security teams

While most security vendors are over-optimizing for incident response against advanced adversaries, a lot of the attacks happen because they do not design the products for the reality of the day-to-day. Specifically,

It takes a lot of effort to try, and then deploy security tools. Cybersecurity vendors have not historically prioritized the onboarding experience, making it hard for new customers to get started with their solutions and make sure that they are properly implemented.

It is hard to fully leverage all the value security vendors offer. Stories where a security team would implement a tool and only later realize that it only enabled 10-50% of the policies are not uncommon. Not only do cybersecurity companies frequently avoid nudging customers to adopt all the features their products offer, but some make it hard to discover the very value they advertise.

Most cybersecurity solutions were designed to be modular and configurable, but very few can be configured at scale, via APIs.

For the longest time, security products were designed as black boxes (or as some like to say, using “secret sauce”), and as such they made it very hard for security teams to understand why the solution made a certain determination. Worse yet, most security tools only expose a limited amount of telemetry they collect, making it hard to investigate alerts and understand what triggered them.

Too many security products are focused on visibility, or in other words, telling the customer that they have a problem. Relatively few are designed to be actionable and to help fix the problems when they are found. As Yaron Levi recently pointed out, visibility without actionability is just noise.

Most security products are poorly designed, which makes them hard to navigate, and even harder to learn. If people on the security team know that using a specific tool requires a lot of effort, they are less likely to keep it up to date.

Despite all the improvements, it can still be too hard to connect different tools to one another, which means that security teams are often prevented from being able to rely on the automation by the very same vendors that claim automation as one of their core value-adds.

I have previously explained that most security breaches could have been prevented by the tools enterprises already have in place; the 2023 Panaseer security leaders peer report has evidence to that effect as well.

Despite what some ambulance chasers would like to suggest, whenever we look at the summary of some of the largest breaches, we rarely hear that a company got breached because it was missing some tool. In most cases, they already have the tools; it’s the fact that these tools are under-utilized, under-deployed, or misconfigured, that is one of the leading causes of security incidents. This makes me conclude that when security vendors over-optimize for fighting advanced adversaries but fail to think about the real day-to-day needs of security teams, they are making it more likely that their customers will get breached.

Building products for real security teams

As an industry, we have invested a lot of time and effort to make everyone feel like security is all about fighting advanced adversaries, not driving specific, measurable improvements. This mindset affects the language we use (hence why we prefer to call IT an “attack surface”), the way we see one another (hence the problem of hero culture in cybersecurity), and how we build security products (over-optimized for detection and response, and under-optimized around user experience, deployment, and maintenance).

There is a lot we as an industry need to evolve; one of these things is how we design security solutions. Security vendors need to start building products for real, not imaginary security teams. Products must be:

Easy to try, deploy, and maintain.

Built with defaults and pre-configurations that promote secure behaviors.

Built to be intuitive, easy to navigate, and quick to learn.

Interoperable and built to easily integrate with any other tooling customers may already have in their environments.

Designed to automate mundane tasks so that skilled engineers can focus on work that requires their expertise.

We need to build solutions that put security practitioners front and center, that help them get promoted, and allow them to be successful in doing what they do. The good news is that we all benefit from taking this approach. Security practitioners are much more likely to love tools built for their real use cases and bring them to companies they join. And, customers are much more likely to be protected if they dedicate time to maintaining their security stack and take full advantage of the many capabilities products they are paying for offer.

This is one of the most accurate write-ups I have read about cybersecurity. You demystified it. Well done, Ross.

I've been in the vendor side of this business for 20 years. This article is spot on! Nice job.