On a hunt for successful cybersecurity startups and unicorn founders

What startup success and failure in security look like, what makes some cybersecurity entrepreneurs succeed and others fail, and how various factors impact their ability to compete in the busy market

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

When you walk around the RSAC Expo floor, it is hard not to get confused about the state of the industry. The number of vendors seemingly all saying the same thing, the cacophony of marketing outreach, and the absence of any tangible differentiation make all that look surreal. However, although it looks like everyone is the same, the truth is that on that floor there are several categories of companies: those that are successful, those that aren’t yet, those that will never be, and those that used to be but failed.

I have always been interested in finding patterns, and as someone who believes that everything is about people, I wanted to understand what makes a successful cybersecurity founder. This is going to be the topic of this article: what makes cybersecurity entrepreneurs succeed and others fail, and how different factors impact their ability to compete in this busy market.

Before we get deeper into these topics, let’s first briefly touch on what success and failure in security look like.

Venture in Security was nominated for European Cybersecurity Blogger Awards 2023. Support our work by voting for us in 2 categories: Best new blog & Best Overall Blog.

How to judge success in the startup land: a philosophical discussion

Defining success criteria: unicorn valuations

The very first task - defining success standards or criteria - isn’t an easy one. Conventional wisdom usually references companies’ unicorn status: if a startup has achieved a billion-dollar valuation, it’s a success. As of June 2022, Retail Bankers International counted 59 unicorns in the industry. I am sure the number has changed given the economic conditions out there but that’s not critical for our discussion.

To understand if a valuation of $1 billion can be used as a metric of success, it’s important to understand what valuations mean more generally and how they are determined. A valuation is a subjective judgment about the worth of a startup, which takes into account its place in the market, the notoriety of its customer base, brand recognition, profiles of its founders, the degree of investor’s belief that they will be able to execute, size of the market, sales pipeline, conversion rate, revenue, and many other factors.

Although as I’ve said, valuing startups is a fairly subjective exercise, for fairness it’s worth highlighting that so is the value of everything else: if there is a demand for a pet rock, people will pay for it. What is important in the context of startups is the economic reality in which value is determined. This is because if founders come with impressive credentials, high confidence, and the ability to paint an optimistic picture and excite investors, they can achieve insanely high valuations even before there is any product or a single penny in revenue.

Whether or not a unicorn valuation can be used as a criterion for success is a tricky question. On one hand, startup valuation is simply a perception of a handful of institutional investors highly influenced by the hype and the demand often manufactured by the company founders. Subsequently, until there is an exit (an acquisition or an IPO), it’s unclear if anyone else on the market is willing to pay more or at least as much for the company that the VCs have paid. And, a lot can happen between the startup proclaiming a unicorn valuation and its exit. A case in point is Cybereason, a company valued at around $2.7 billion in mid-2021 which has recently raised money at a valuation of roughly 10% of that, and lost its unicorn status. It remains to be seen what Cybereason’s exit will look like but it won’t be anything near or above the $2.7 billion.

Despite all the fluctuations in valuations, they are still a solid metric. This is because of the incentive systems they create for investors who put their money into the company. Once a VC firm has put a substantial amount in the company valued at over $1 billion, it is in its very best interests to broker introductions and do anything possible and impossible to see the company sell for more than what it was estimated to be worth at the time of the investment. This is why VCs with solid networks are seen as highly desirable: not only can they sometimes add a lot of value to boost the company's growth, but they also help startups to exit at their pinnacle.

Defining success criteria: exits

Another possible and, one may argue, much more tangible way to judge what success in a startup world looks like, is the value of the company at the time of an exit. In particular, we are most concerned with two scenarios: initial public offerings (IPOs) and acquisitions.

Currently, less than 30 cybersecurity companies are listed on the US stock exchange. I have previously counted 24 of them, but learned that there are a few more so 30 seems like a good estimate. Valuation at IPO is a stronger and more convincing value; not because it’s somehow more objective but because a much larger pool of buyers - brokers, investment banks, and the like - have to be convinced the company is worth the price it’s asking.

The same is true for mergers and acquisitions (M&As): before another entity is willing to pay real money for the startup, its valuation is nothing more than imaginary money. This is why founders of startups are often called “paper millionaires”.

Success and failure in cybersecurity have a unique shape

What failed security companies look like

Both success and failure in cybersecurity have a rather unique shape; let’s discuss what it looks like by starting with failure.

There is a commonly accepted “wisdom” that 9 out of 10 startups fail: it is being repeated in many startup programs, accelerators, incubators, and by any author who cares to talk about entrepreneurship. I have a lot of issues with this number because it is so broad, generic, and devoid of any context that there is just no way it is useful to anyone and it’s most certainly not true. This number seems to be lumping many things into one place: if a student started a company on a Summer break, will it be counted the same way as a company built by three co-founders with ten years of experience in their fields? If a VC-backed company achieves 10x not 100x return and doesn’t make a material difference to the VC, is it still a failure for the founder & the team? If a company ends up being entirely bootstrapped and turns into a sustainable source of revenue for 50 people including founders and employees, is it a failure or a success? I don’t necessarily have an opinion about any of these, but the point is that the “9 out of 10” number isn’t helpful because every situation is highly contextual.

Does this mean that security startups succeed more often than fail? Not at all, but there are a few things about failure in cybersecurity that deserve a deeper look.

As I discussed before, “The trust-based product adoption and slow sales cycles mean that instead of having a limited few companies take the market by storm, we typically see several cybersecurity startups solving the same problem operate in parallel and generate enough revenues to survive. This explains another observation: cybersecurity ventures do not fail at the same rate as startups in other industries. While some that don’t reach traction do inevitably end up folding, most will find at least a handful of loyal customers - just enough to stick around for years, and sometimes - decades. A few will grow fast, but many will end up making enough money for their founders to live comfortable lives and not have to go back to a job.” - Source: Why there are so many cybersecurity vendors, what it leads to and where do we go from here

The significance of this insight is hard to overestimate because in most industries, failing a startup means going out of business quickly. In cybersecurity, however, a large percentage of ventures can get enough customers to extend their existence for many years. Although the conventional wisdom driven by the investor expectations of growth may consider these a failure, it comes down to the goals founders established for their entrepreneurial ventures: if all they want is the ability to build cool tech and get paid roughly the same they’d get on the market but without having to deal with bosses, HR, and performance reviews, they may very well see this a success.

On the other hand, failure to get big in cybersecurity can often look like success. This is because of the frequency of acquisitions and the fact that many companies that built a usable product, or a rockstar team, can still get bought (commonly for an undisclosed amount). Larger, more successful, or better-funded players are constantly looking to add new capabilities to their portfolios. Most point solutions dream of becoming a large platform, and as I have discussed before, cybersecurity innovation is more often acquired not built in house. These facts and the resulting M&A activity in the space enable founders who have failed to get significant traction to sell their struggling venture and in a short time start a new one, armed with all the learnings, connections, and a much stronger profile of the second-time founder who has exited their first company. I would say it’s a decent outcome for what most VCs would agree is a failed investment.

What successful cybersecurity companies look like

If defining what failure in cybersecurity looks like is hard, figuring out what success is can be even harder. Is it, as we’ve discussed, the unicorn status? It’s a good signal but probably not a great measure given what we’ve learned from the story of Cybereason, and what we are likely to see as other pre-IPO companies with unicorn status will need to extend their runway in current economic conditions. Is it the valuation at the IPO? Could be, with the caveat that we must not forget that the role of luck extends to IPOs. The fact that SentinelOne completed its initial public offering on June 30, 2021, and Cybereason saw its valuation tank because the market went down in early 2022 and it could no longer go public, is as much (or more) a result of bad luck as it is an outcome of poor planning. Or, should we judge success by looking at the valuation of the company 6 months, a year, or a few years after the IPO? It’s not a secret that the value of many public companies doesn’t exactly go up with time.

Either way, here is what’s interesting. The industry's largest database of cybersecurity companies by IT-Harvest counts 1,821 cybersecurity vendors in the United States. Of those, under 30 (less than 2%) are publicly listed on the US stock exchange. This makes it clear that the vast majority of cybersecurity companies won’t go public.

Similarly, most won’t get acquired at a unicorn valuation. For anyone who follows the market analysis published by Momentum Cyber, it won’t come as a surprise that a fantastic outcome for a small percentage of cybersecurity companies is acquisition at $200-400 million, and a good price for other startups that can be deemed successful is somewhere between $25 and a $150 million, depending on their stage and the amount of funding the company received.

These numbers make it clear that it is almost equally unlikely that a cybersecurity startup tackling a real problem will be either a sweeping success or a complete failure. The vast majority of the companies in the industry will fall somewhere in between these two extremes.

In a search for successful cybersecurity founders

As an industry enthusiast, product leader, and angel investor currently co-running the ViS Syndicate, I often think about where the next wave of cybersecurity innovation is going to come from. A critical part of this is figuring out what traits and characteristics are shared by successful founders in the industry. I would like to share some observations on this matter.

Cybersecurity founders need context

Unlike in some other industries where an outsider can find an opportunity and act on it, in cybersecurity, most of the innovation is so technical and close to the metal that it would be very hard for someone without deep domain expertise to make sense of it. This does not, however, mean that a successful founder must be an engineer: what’s important is that they are able to understand the problem, navigate the dynamics of the industry, and be perceived as credible to the buyers and investors.

These domain knowledge, credibility, and connections can be achieved in several ways, including by being a security professional, a security leader, by serving in a cyber-focused role in the military, and by helping build another cybersecurity company. Founders of most successful cybersecurity companies tend to have different combinations of these backgrounds, for instance:

George Kurtz, the co-founder, and CEO of CrowdStrike, was previously the founder of Foundstone and chief technology officer of McAfee

Jack Naglieri, founder & CEO of Panther, was a security engineer at Airbnb

Oz Golan, co-founder & CEO at Noname Security, was a developer and security researcher at Israeli Defense Forces

It is common for security founders to spend a substantial amount of time in their segment before starting a company. This makes intuitive sense as for building SIEM 2.0, founders must know SIEM 1.0 deeply (ideally they would have worked on the team that built it). It’s statistically unlikely that someone new to the space can just come up with a great idea that accounts for all the nuances and inherent complexity the industry comes with, and execute it.

The need for context, and the fact that most security founders are experienced practitioners, also means that a typical entrepreneur in the industry tends to be older than founders of B2C and most other B2B industries. It’s practically impossible to find students and recent graduates without any experience in the field starting an enterprise-focused security company and turning it into a visible, successful industry player. It is rare to see security entrepreneurs in their early 20s but not uncommon to see people start their first security venture in their early 40s and even 50s. This makes sense as one would need to be deeply familiar with the security operations in the enterprise and understand the complexity of different environments, as well as the dynamics when it comes to purchasing. However, “uncommon” doesn’t mean “impossible”, and Vanta founded by Christina Cacioppo, ex-product manager at Dropbox, is a good example that it is indeed possible even if highly unusual.

Experience from mature security teams and understanding of those that aren’t

If you have been reading Venture in Security for some time, you know some of the trends and concepts I think about: the move from promise-based to evidence-based security, the rise of security engineering, the importance of adopting a security-first mindset, the rising importance of “data gravity”, and ultimately, the need for practitioner-focused cybersecurity. This isn’t an accident, but a well-shaped thought rooted in the following:

The old generation of security analysts who believe that to secure an organization, it’s enough to simply deploy a “tool” and click “enable” in the web UI is bound to be replaced by mature, technical security practitioners. This shift is going to take time (as Max Planck cynically declared, “Science advances one funeral at a time”) but it is inevitable. The security of the future will look a lot like software engineering.

It is very unlikely that we can keep adding more and more security tools each using its own data and stitching them all together. Now it’s 20-60 or so tools; what are the chances that in a decade from now as new attack vectors emerge, we can still stitch together 100-200 widgets and continue to operate? A security data layer or a similar model where different tools are able to leverage a common data fabric is if not necessarily inevitable, then badly needed.

A lot more of what we think about as security will have to be built into the products we use. As I’ve explained before, the recently released US National Cybersecurity Strategy is a step in the right direction. Under the new Strategy, software creators rather than the end users should be the ones responsible for security.

There is much more, but this is a good summary to get back to our discussion. When I think about where the innovation in the cybersecurity industry is going to come from, my mind immediately goes to technical security practitioners. This is also why we’ve developed a thesis for our angel syndicate centered around security practitioners and got over 70 members that include security engineers, architects, detections engineers, analysts, and researchers from all over the US and globally join us on our mission.

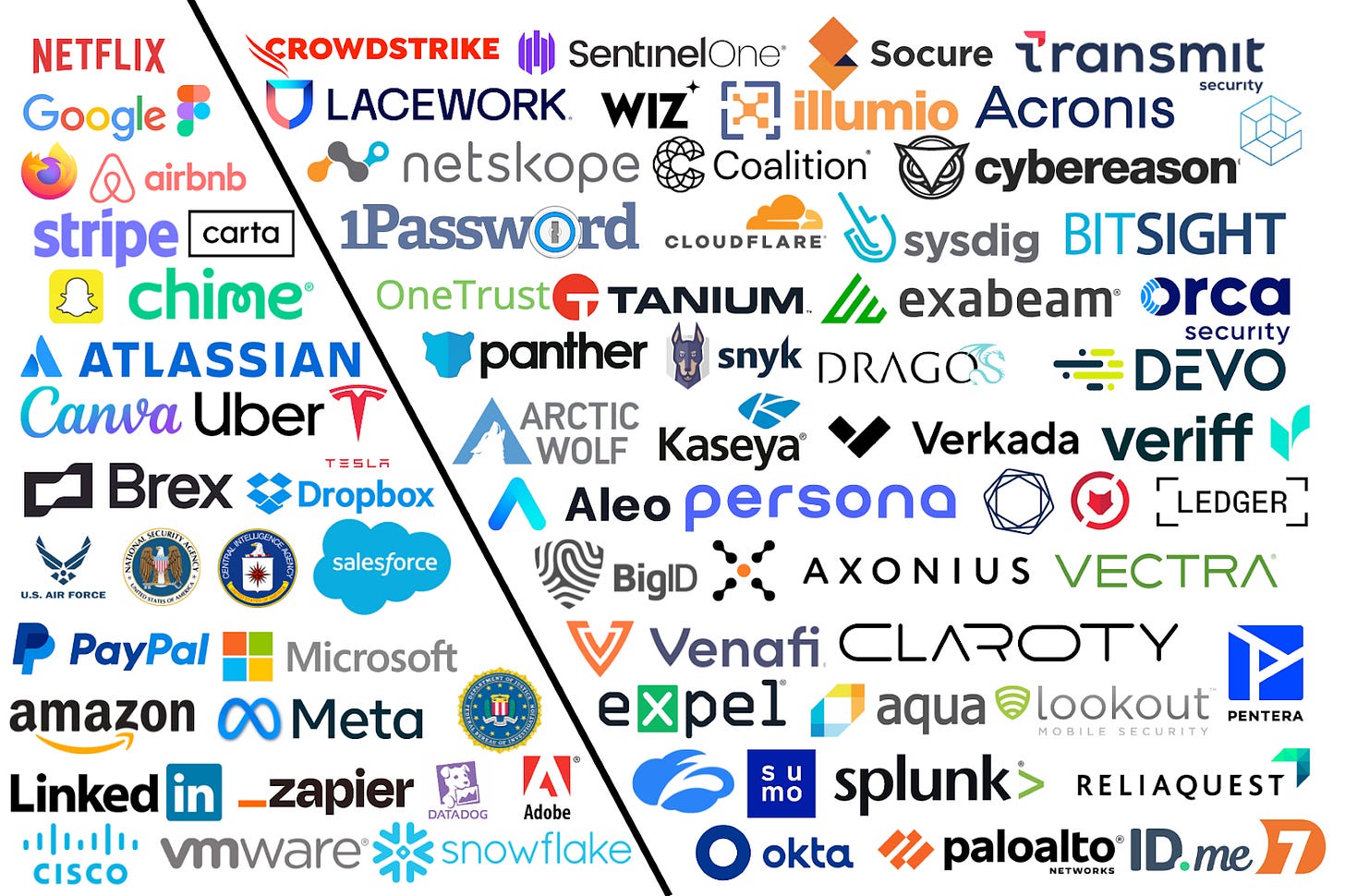

Highly mature security teams at cloud-native enterprises

The first place to look is highly mature security teams at cloud-native enterprises. Think of Google, Netflix, Dropbox, Brex, Figma, Meta, Airbnb, Amazon, Uber, and others. Typically, they are backed by prominent VCs, most are headquartered or have a large presence on the West Coast, and a solid security budget to not only hire the top security practitioners but also to build their own tools. Netflix and Google are fantastic examples of this as both are known for building their own security infrastructure instead of using conventional vendors (although that has recently started to change a bit).

Many of the companies that fall under this category are many years ahead of the rest of the industry when it comes to their security practices, and the problems their security teams are solving aren’t yet solved in other enterprises. This can happen for one of the three reasons:

Their problems are so niche and specific that nobody else on the market is ever going to face them

Other companies experience the same challenges but do not have the talent, resources, or know-how how to solve them

Other companies do not yet experience them for a variety of reasons but it is apparent that they will be facing them in a foreseeable future

Security practitioners from these cloud-native enterprises who become founders have, among others, the following strengths:

A great network among some of the most forward-thinking security people in the industry on the planet

A good understanding of what it takes to build a product that comes from the fact that most if not all of their former employers were product companies with a solid product mindset

Typically a good ability to separate the three categories of the problems discussed above and avoid working on those that are too niche for the broader market

The resulting ability to raise capital from the top VCs in the Bay Area and move fast to execute their vision

When companies founded by security practitioners from the cloud-native venture-backed companies stall after Seed or Series A rounds, this typically happens if:

Founders lack the understanding of what security teams outside of the Bay Area look like. Unfortunately for them, outside of the VC-backed, well-funded players typically headquartered on the West Coast, an average security organization doesn’t employ large teams of detection engineers and threat hunters well-versed in Python, the world’s best talent in cloud security, etc. Those who choose to optimize their products for power users exclusively tend to struggle in gaining traction with the rest of the market.

Founders lack the understanding of what security infrastructure in companies outside of the Bay Area looks like. This commonly happens when they make decisions to tailor their products to cloud-only enterprises. Taking this approach can enable them to grow really fast on the West Coast, but once they start talking to banks, retail, manufacturing, utilities, and other companies, they realize that these prospects are anything but cloud-only.

Overall, I am convinced that security practitioners with experiences at some of the largest and most influential tech companies on the planet are one of the strongest forces with the potential to enable the maturation of the cybersecurity industry. Not only do they possess domain expertise and experience solving hard problems at large scale, but they also have a strong product mindset that is so critical for building a successful company.

Security practitioners with experience working on teams of large enterprises and/or offering services to the governments

In this second category of people, I would mention people who fall under several broad sub-segments which include:

Security professionals with experience working in large enterprises

Security professionals with experience working in service companies

Security professionals with experience offering services to the government

Security professionals with experience serving in the cyber-focused parts of the military, three-letter agencies, and in special forces

Security professionals I put under this, admittedly, broad category, tend to have incredibly deep and diverse technical experience in cybersecurity. Serving in the military and defending critical infrastructure, for example, allows them to build the level of defensive, and often - offensive expertise not available to anyone else. Some of the strengths they possess include:

Technical depth and a strong sense of mission

Strong network with those working for the government, large multinational corporations, and organizations

A great experience providing services and the ability to recruit strong security practitioners

When companies founded by security practitioners struggle, this typically happens if:

Founders do not have experience building products and taking them to the market. Those who haven’t worked in product companies and those with strong experience in managed security services or as government contractors tend to lack the right mindset and an understanding of what it takes to run a product company.

Founders with experience in the US military and divisions such as US Air Force and agencies such as the CIA, NSA, and FBI may thrive with government contracts but struggle to sell to the private sector.

When these challenges are overcome, or when people from this category partner with co-founders experienced in running product companies, mentors, or accelerators such as DataTribe, they can create highly successful enterprises. A great example is Dragos, a DataTribe portfolio company and a leader in OT security.

A brief look at three cybersecurity startup ecosystems

The United States was and remains the place to build a cybersecurity startup. When looking at the country from the angle of cybersecurity startup ecosystems, it is easy to see three main centers:

San Francisco Bay Area

New York

Washington DC-Baltimore Area

Each of these has its unique characteristics. The San Francisco Bay Area has the strongest startup and venture ecosystems in the world, a high appetite for risk, and a well-developed product culture. New York, on the other hand, is a place with the highest number of CISOs and large enterprises, strong culture of enterprise sales, a decent understanding of product, and a much lower appetite for risk when it comes to buying security tooling. Lastly, Washington DC-Baltimore Area has been seen as an emerging ecosystem with the highest number of senior security talent per capita but a comparatively low understanding of what it takes to take products to the market, a service-based view of security, and few investors willing and able to allocate capital to cybersecurity startups.

In the past several years, this previously well-defined picture has started to shift and evolve. While the San Francisco Bay Area was and will remain for the years to come as a place to build a cybersecurity company, we saw rapid maturation of the DC ecosystem with an ever-growing number of successful product companies and an increased inflow of capital from both local VCs and investors from around the country. Areas such as Austin and Dallas in Texas are starting to emerge as up-and-coming centers for cybersecurity startups as well. The rise of remote work and the willingness of investors to look beyond San Francisco and New York for promising ventures makes it much less important where the startup is located, and if it has a physical office to begin with.

Closing thoughts

In trying to answer the questions of what makes cybersecurity entrepreneurs succeed and others fail, and how different factors impact their ability to compete in this busy market, it’s important to not get overly excited in finding a “correct” answer because, whether we like it or not, there is none. It is critical to remember that a multitude of factors make or break success, and the cybersecurity industry is not an exception. It is true that founders must solve a real problem, keep in mind the size of the total addressable market, and get the timing right, among many other things. But, at the end of the day, it’s all about people - passionate entrepreneurs willing to make a bet on their vision of the future and working hard to make it come true. Everything else matters significantly less.

"The industry's largest database of cybersecurity companies by IT-Harvest counts 1,821 cybersecurity vendors in the United States. Of those, under 30 (less than 2%) are publicly listed on the US stock exchange. This makes it clear that the vast majority of cybersecurity companies won’t go public."

-> Did you count only US-origin companies or other companies that have been established somewhere else and do business in the US? Those other companies may be listed in different stock exchanges than the US and indeed are public.

In that case we can trust https://axcrypt.net/ . This is also a startup company and doing well among its competitiors in American and European countries.