Future of cyber defense and move from promise-based to evidence-based security

A comprehensive look into the trends shaping the future of cyber defense.

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

The maturity metaphor

Cybersecurity is full of metaphors so let me start this article with a story. When I was in my early teens and up until my twenties, I didn’t pay a lot of attention to my health. I think most of us do the same: if we feel okay, we assume we’re “healthy”. That is until we either learn that it’s much more nuanced than that, or until we develop a disease that requires immediate attention.

Most diseases are treatable at their early stages, but noticeable symptoms often don’t appear until it’s too late. Hence lies the problem: if you just go by the “feeling of health” and don’t do regular check-ups, when something becomes an issue, it will likely be too late.

I was lucky to have learned that health is all about fundamentals without any traumatic triggers. At a certain point, I realized that I cannot stay healthy long-term unless I pay attention to the multitude of components that all affect your well-being, including sleep, diet, exercise routine, and daily habits, to name a few.

The evolution from feeling-based or trust-based health (“I feel okay”) to evidence-based health (“I have tested and confirmed empirically that there are no signs of disease”) is very similar to the evolution that we’re now seeing in security. Namely, move from promise-based security to evidence-based security.

Move from promise-based to evidence-based security

Traditionally, companies looking to secure their operations have relied on the promises of vendors to keep them safe. When a CISO (Chief Information Security Officer) would sign a contract with a security vendor, it would essentially buy a promise that the vendor would stop the breach when it happens. This approach worked, and it’s worth noting that many vendors in the cybersecurity space have been and still are doing a fantastic job preventing the most common attacks. However, with the number of attack vectors continuously growing, mature security professionals have come to an understanding that it is simply not possible to stop all breaches and prevent all ransomware, despite what the marketing materials would claim.

This, among many other factors that will be discussed later in the article, has led to the shift from promise-based security to evidence-based security we are witnessing today.

What does this mean? In practical terms, there are multiple dimensions on which evidence-based (proof-based) security is drastically different from the trust-based (promise-based) approach.

Mature security professionals know that security is a process, not a feature. The best way to build a security posture is to build it on top of controls and infrastructure that can be observed, tested, and enhanced. It is not built on promises from vendors that must be taken at face value. This means that the exact set of malicious activity and behavior you’re protected from should be known and you should be able to test and prove this. It also means that if you can describe something you want to detect and prevent, you should be able to apply it unilaterally without vendor intervention. For example, if a security engineer has read about WannaCry, they should have the ability to create their own detection logic without waiting a day or two until their vendor does a new release.

Moving from promise-based security to evidence-based security shifts the ownership from third parties to security teams. When the board asks a CISO — “There is log4j vulnerability — are we protected?”, it most certainly doesn’t want to hear “I don’t know — hopefully, our vendor will take care of that”. The CISO should be able to say — “This is the security coverage we have in place for log4j. This is how it is detected, and this is the action we are taking to address it”.

This ability to control one’s own destiny is becoming more and more critical as every environment is unique. An experienced security engineer who knows their organization’s environment can think of many behaviors that are very specific to their company and critical to detect or prevent. The kind of behaviors that any commercial vendor would not have the out-of-the-box coverage against simply because they cannot afford building logic that can only be used by 0.01% of their customers.

A security person tasked with protecting their unique environment should not have to build all the infrastructure from the ground up (like building an antivirus or their own endpoint detection & response system). Instead, they need to have the ability to know what they are protected against. Knowing is very different from being promised. At any point in time, they should be able to say “Here is the MITRE ATT&CK framework, here is how we interpret it for our organization, and here are the tools we’re leveraging to help us protect against the attacks”. We’re not saying they need to “own” all their detection knowledge, just that it should be transparent and measurable.

Before we dive deeper into the details of this approach and the trends leading to its adoption, it’s important to call out that evidence-based security does not eliminate prevention. Instead, it acts as a foundation for it. Malicious behaviors that can be prevented should be prevented, and that prevention should come with full transparency — what was detected, how it was detected, against what sources was it checked, and how the determination to prevent it was made. If a security professional deems that a behavior in question is safe, they should have the ability to allow it or adapt the rule for their organization. Then, if we think something malicious is happening, we need to collect the data, analyze it, retain it, and use the available tools, so that we can deliver curated events to humans to make intelligent decisions.

Trends leading to a tectonic shift in how security is done

The concept of evidence-based security is not new. Mature enterprises like Google, Amazon, Facebook, Netflix, and others who are handling the data of millions of customers have been practicing it for a long time. What is new is that this approach is gaining traction outside the small number of enterprises. Here are the trends leading to a tectonic shift in how security is done.

Weak correlation between results and security spend

Cybersecurity budgets have been going up in the past decade, and COVID pandemic has only accelerated the increase forcing organizations across the globe to adapt to the new, remote-first world.

At the same time, cybersecurity stats are not encouraging:

As of 2019, security breaches have increased by 11% since 2018 and 67% since 2014.

Attacks on IoT devices tripled in the first half of 2019.

More than 93% of healthcare organizations experienced a data breach between 2017 and 2020.

We are seeing today that increasing spending on security has not led to a reduction in cyber attacks. Arguably, businesses are not more secure today than they were yesterday. While it is hard to know where we would be if companies didn’t invest as much as they do in security, intuitively there is an expectation that the number of cyber incidents would be inversely proportional to the defense effort.

Business demands measurable results

In the past few decades, business has been moving from activities-driven to outcome-driven approaches in everything from marketing and sales to product, engineering, human resources, and arguably any other functional area.

In practical terms, this means that sales teams are focused on reaching their quota, product teams are optimizing for monthly active users (MAU), annual recurring revenue (ARR), and a number of other metrics while marketing tracks conversions and engagement. There is a lot to be said about the so-called vanity metrics, but the important fact remains true: instead of being asked “What are you doing?”, business leaders are expected to explain “What outcomes have you achieved and why do they matter?”.

Security is one of the functions that has largely preserved focus on activities over outcomes. Some would say that it’s because security is hard to measure. While that is true, cybersecurity professionals developed the MITRE ATT&CK framework — a de-facto standard in the industry.

“MITRE ATT&CK® is a globally-accessible knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques (TTTs) based on real-world observations. The ATT&CK knowledge base is used as a foundation for the development of specific threat models and methodologies in the private sector, in government, and in the cybersecurity product and service community.”

Source: The MITRE Corporation

Anything worth protecting has an associated return on investment (ROI). There are always trade-offs, and you can’t just secure everything everywhere at all times. Security teams now have the ability to benchmark their coverage against the generally accepted and constantly evolving knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques. This enables security leaders to shift the narrative from actions-based to outcomes-based: instead of saying “We’ve spent 60 hours and implemented tool X”, they can now say “We’ve invested $3,000 and that allowed us to build security coverage against 13 more ATT&CK TTTs”.

Increasing complexity of security and customer environments

The type and volume of security data generated by organizations today have been growing exponentially and will continue to grow in the next decade. The ever-increasing adoption of SaaS tools means that security data is now distributed across hundreds of platforms with no centralized control. Most importantly, company systems can no longer be protected with a firewall.

While security is becoming more complex, the vast majority of vendors continue to market their offerings as a solution to all problems. The number of providers promising to “stop all breaches”, “stop all ransomware”, “stop all attackers”, and “eliminate all zero days” makes it hard to trust any marketing promises. This is especially true given that there is strong empirical evidence that leading cybersecurity vendors aren’t all that good at what they claim.

Each company’s crown jewels are different. For some it’s their intellectual property (IP), for others it’s data, for others it’s the integrity of their algorithms. You need to know what these crown jewels are, how they are handled, who has access to them, and other important factors, before you look for ways to protect them.

Even more importantly, each company’s environment is unique. Because different companies use different tools, if you want to detect data exfiltration or insider risk at Google, you will need to have different alerts and detection logic than if you want to do it at Salesforce. Large security vendors can’t fully handle these differences as their business model works if they write detection logic that applies to 90%+ of their customers, not to 0.1%.

None of this means that existing EDR, XDR, SIEM, and similar vendors don’t do a good job. On the contrary, they are incredibly important. However, it is also important to recognize that one size fits all approach has its limitations in security. Security is partially a problem of visibility, and visibility has multiple layers. Antivirus, EDR, and similar black-box products are only exposing the top layer — “I blocked X, now you are safe”. While it is a good start, it’s no longer sufficient. Mature security professionals require visibility into deeper layers of technology to understand what inputs were used to make that determination, what did the product check against, etc.

As complexity increases, followed by the increasing level of maturity of security teams, companies start to think more in terms of capabilities and less in terms of products. “What box do I need to buy to keep safe?” is shifting to “What capabilities do I need to secure my unique environment?”, “How do I know I am protected?”, and “What exactly am I protected against?”.

As a security professional, taking the evidence-based approach to security enables you to say: “We have identified these five risks that are important in our environment. Here is how we are protecting against them. We have tested our coverage and are able to prove that it addresses the risks in question. We aren’t relying on vendor X whose artificial intelligence and machine learning models should stop that”. This makes cybersecurity a science.

Security tools proliferation

Today, an average organization has over 70 security tools. While the number can be substantially smaller for small companies and significantly larger for enterprises, it is not going to be an overstatement to say that there are too many security tools an average company has to manage.

There are multiple reasons why this is a problem:

More tools does not mean better security. Not only is there a lot of overlap between what different vendors are offering, but adding more tools to the organization’s environment creates more failure points and weakens security.

More tools require larger security budgets and more attention from an already overstretched security team.

There is an upper limit to the number of agents you can install on the endpoint. The more agents are crammed on the endpoint — the more horsepower is used to just run the endpoints, reducing performance and leading to user frustration.

The more separate products a company uses, the harder it becomes to automate security operations.

It is very common for companies to buy tens of products and then five more to glue them all together. Doing this made sense when a lot of these tools were very novel and not well understood: they provided a new concept, addressed a new need, and a new thought in the industry. As we mature as an industry, the set of tools companies are looking to buy is going to go down. This is primarily because security professionals are starting to understand these tools more, and are seeing them less as a widget they buy from someone and more as a collection of capabilities they can access to do their job.

Buying many separate tools each promising to “stop something” is not scalable. Building individual capabilities in-house is expensive, and so is stitching them from open-source tooling. Security professionals are looking for commercial-grade tools and capabilities that give them full control over what is happening in the environment, and how each of these pieces contributes to the larger picture.

This proliferation hurts evidence-based efforts because it makes it very difficult for defenders to keep a mental model of what controls and visibility is available to them.

Growing maturity of security professionals

The security talent landscape is going through a number of tectonic changes.

We are seeing an increased focus on skills and abilities over degrees, specific tooling, and certifications. The new generation of security professionals is learning the fundamentals of security in Discord forums, capture the flag (CTF), OpenSOC, and similar hands-on competitions, by using open-source and accessible product-led commercial tools, at Black Hat, BSides, DefCon, and other conferences and training. They don’t just go to Gartner or G2 to see what anti-malware products are ranked amongst the top five; they know the mechanics of how malware works, which enables them to understand exactly what a tool is doing and where its limitations are.

Mature security professionals go beyond traditional degree programs recognizing that security is changing daily, new vulnerabilities are being discovered continuously, and to stay current they need to be on top of these discoveries. In the recent Voice of the SOC Analyst report, coding and knowing how to operationalize MITRE ATT&CK were named as the top skills needed to succeed as an analyst.

FAANG (Facebook — now Meta, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Google) companies as well as progressive Silicon Valley startups that handle large amounts of data such as Carta, Snapchat, Intercom, Auth0, and GitLab among others, see security as an integral component of the business. These organizations recruit technical security professionals with a strong understanding of security fundamentals, not someone who is looking to install a magic box from a vendor. The same can be said about the professionals working in the military, Department of Defense, FBI, and other governmental institutions focused on cybersecurity.

That is not to say that everyone is taking this approach. As a product professional, I get to talk a lot to security professionals from different backgrounds. After many of these conversations, I am seeing a growing divide between the two kinds of security professionals: those focused on security fundamentals and those focused on security tools. The first category — those focused on security fundamentals — are generally deeply technical, with the strong ability to build a holistic understanding of the organization’s security posture, identify gaps and develop (often — build) the solutions, from setting up the infrastructure to writing detection and response rules. The second category is people who rely on tools to do the job; they are the ones who think in terms of boxed product categories (“You need an EDR from vendor X, a SIEM from vendor Y, and a SOAR from vendor Z because these vendors are in the top right corner of the Gartner report”).

For anyone in the industry looking to understand the level of maturity of security organizations, here is a useful tip. Companies that employ security engineers, detection engineers, security architects, and similar are what I would say security leaders. Those that have exclusively security managers & analysts are more likely to be focused on implementing products and trusting vendors to keep them safe.

It’s important to acknowledge that small businesses are not likely to be able to attract experienced technical security professionals, nor should they. However, promise-based tools are not the only alternative they have as there is a growing number of security service providers ready to help. We will talk more about service providers in the paragraphs below.

Rising insurance premiums

Insurance premiums have been skyrocketing, driven by the increasing loss ratios for cyber insurers, large payouts from ransomware attacks, and exposure due to remote work. Cyber losses are hard to underwrite, in part because there is not enough data but also because it’s hard to correlate specific measurable factors with cyber breaches.

All this is forcing insurers to implement more stringent underwriting guidelines and to become much more data-driven. The need for insurance companies to establish a quantified security posture baseline is fueling the growth of startups in this space and is one of the contributing factors to the trend of evidence-based security. Cyber insurance underwriting and risk evaluation will one day get reduced to insurance providers being able to run the models and simulations based on quantitative data, the way it can be done in other areas of insurance today.

Emergence of the new generation of service providers

Historically, managed security service providers (MSSPs) have built their business as resellers of security products. The scope of “security services” would often be defined as follows:

Assess the environment

Select & implement a standard set of security products (most commonly from a list of partners or preferred vendors)

Monitor the implemented products and triage the alerts

Essentially, the security service provider would rely on vendors to take care of their customer’s environment. While this reseller model is likely to continue its existence, two trends are shaping the future of security services.

In the past decade, we have witnessed the emergence of technical cybersecurity consultancies — teams of security engineers, security architects, detection engineers, and others working to provide holistic security to their customers. The list of companies in this segment includes Soteria, Recon Infosec, TrustedSec, Binary Defense, and Black Hills Information Security. This new kind of MSSPs, MDR (managed detection & response), and boutique security consultancies add value by tailoring the coverage to different environments and deploying technical talent to address security holistically, instead of implementing third-party vendors and relying on them to keep their customers safe. Recon Infosec even works with channel partners as resellers of their MDR service, creating a somewhat unique precedent (most commonly, channel partners sell security products, not security services).

We are also seeing the emergence of subscription-based, transparent service providers such as Nano Cyber Solutions which offer holistic security services to SMBs. Unlike traditional service providers, the scope and pricing of these all-in-one managed cybersecurity subscriptions are entirely transparent.

We anticipate that in the next decade, we will be seeing growth in the number of technologically fluent cybersecurity consultancies acting not as resellers, but as technical advisors that secure their customers. Subsequently, smaller companies that can’t do security on their own, will increasingly stop buying “magic” tools or building security teams. Instead, they will be getting services from experienced security service providers. While it is true that many companies will only change when they have a security event, the frequency and scale of cyber breaches will make businesses shift their thinking.

Emergence of the supporting vendor ecosystem

To support a new approach to security, it is necessary to have the right vendor ecosystem. In the past few years, we have started seeing a shift in the industry going from “magic boxes” a company needs to install in their environment to be “safe” to security infrastructure and tools professionals need to do their job.

It used to be that security infrastructure was the core value proposition of open source while commercial vendors would offer black box, “magic” tools that “just work and keep you safe”. People who understood the fundamentals of security would stitch tens of open source tools to do what they needed them to do. This approach worked but came at the high cost of labor and the absence of support: if you needed something, you had to build it yourself.

Some enterprises built their own solutions with the mindset “we can do more for less”; the time it took to build, maintain, and scale these solutions has generally been higher than initially anticipated. Additionally, when a team member who built the security tooling would leave the organization, the solutions they put in place would end up being abandoned, outdated, and after some time — irrelevant.

There was a strong need for vendors who offer security tools and capabilities instead of promising a “magic pill” that solves all problems. The gap in the industry has led to the emergence of cloud-native, API-first, high-scale security vendors. We are seeing more and more vendors such as Panther, Tines, and LimaCharlie among others which make it easy for people to integrate external tools and provide the ability to fully control what is happening in the customer’s environment.

Customers can use LimaCharlie to collect the data from any source (endpoints, network, external sources, browser, etc.), detect & respond in real-time, build their own detection & response ruleset or use pre-built rulesets, and access any of the 100+ security capabilities while paying only for what they use.

Similarly, if an organization is focused on detection, it can use Panther to collect all of their logs in one place and detect specific behaviors.

To identify noisy scanners and opportunistic attacks, organizations can use GreyNoise.

To test security coverage, security teams can use FourCore, Prelude, and watchTowr, or the open-source Atomic Red Team by Red Canary.

To address the gaps that have been identified during testing, and to access detections as code, SOC Prime, Sigma, as well as the Elastic rulesets will come in handy.

To automate and orchestrate security, the low code security automation platform Tines can be used as well.

Neither of the above tools promises to “stop 100% of ransomware, breaches, advanced persistent threats (APTs) and zero-days with next-gen AI magic box”. Instead, they are tools security professionals can use to do what they can do best — leverage their skills and knowledge to secure the unique environment of their organization . Best of all — except for Panther, all the above-mentioned tools can be accessed without talking to a salesperson or signing a long-term contract, — an approach known as product-led growth. As usage-based pricing becomes a norm in the industry, adopting commercial security tools no longer means paying for the capabilities companies do not need.

While open-source is and will continue to be a critical component of security infrastructure, it is now an integral part of the same ecosystem that unites both open source tools and commercial product offerings. When security vendors are becoming more transparent, more integrated, API-first, and accessible without pricing negotiations and long-term contracts, the lines between commercial and open source are blurring.

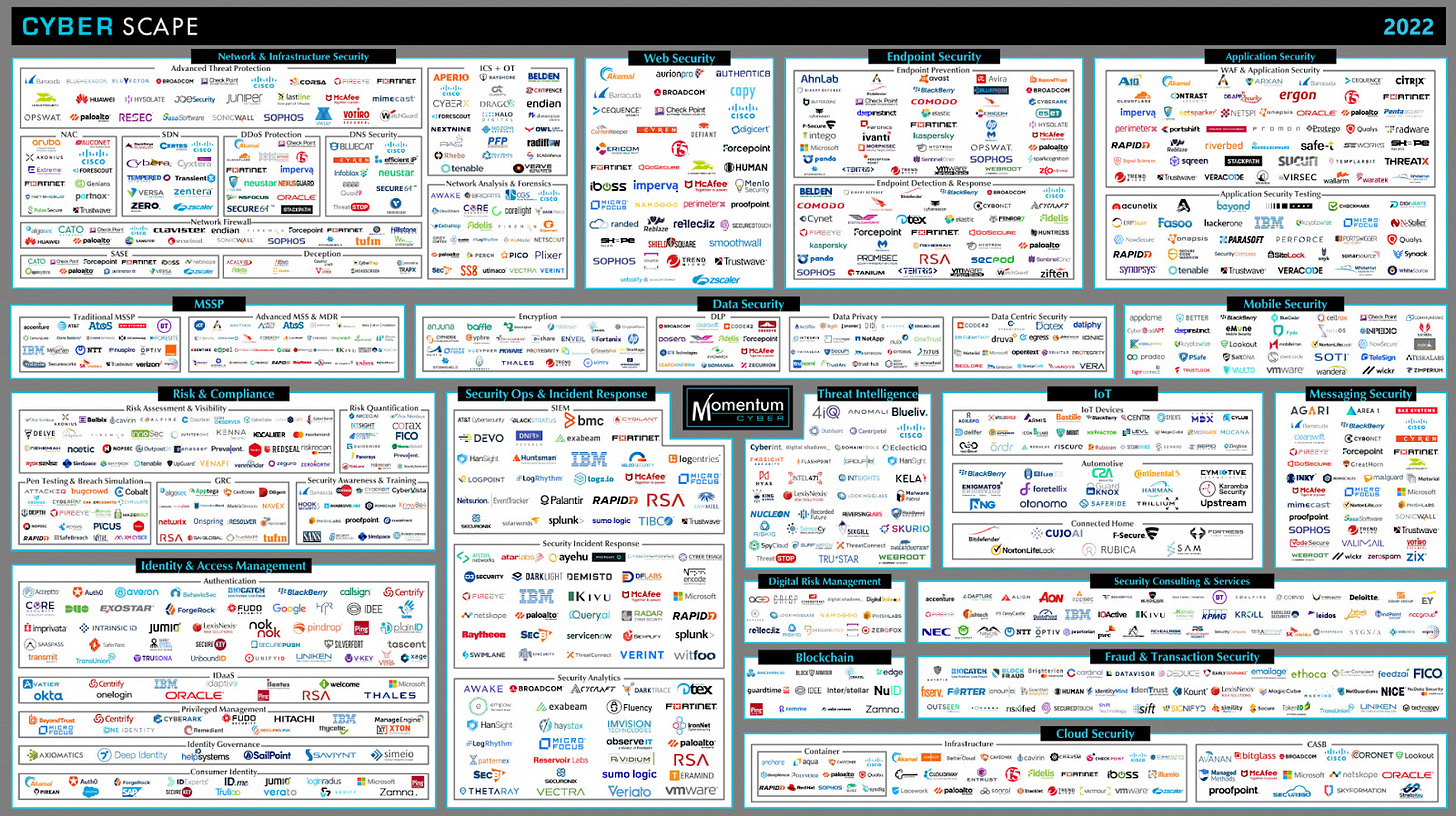

Source: MomentumCyber

Establishment of security frameworks

The US government recognizes that there are no silver bullets when it comes to cybersecurity and that organizations have unique risks — different threats, different vulnerabilities, and different risk tolerances.

In an attempt to increase the level of security, the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) developed a Framework that consists of standards, guidelines, and best practices to manage cybersecurity risk. While the use of the Framework is voluntary for industry, Executive Order 13800 from 2017, Strengthening the Cybersecurity of Federal Networks and Critical Infrastructure, made the Framework mandatory for U.S. federal government agencies. Private companies that work with the US government and fall anywhere within the supply chain for a federal agency must also comply with NIST standards.

The NIST Framework helps companies to assess and improve management of cybersecurity risks which, in turn, should “put organizations in a much better position to identify, protect, detect, respond to, and recover from an attack, minimizing damage and impact”. It is not designed to be implemented as an un-customized checklist or a one-size-fits-all approach for all organizations that choose or are mandated to adopt it. Instead, it goes to first principles talking about the components of security and offering guidance about going about them.

The NIST Framework is one of the many attempts of governments around the globe to compel companies and organizations to improve their security posture. The establishment of frameworks, compliance requirements and best practices that are focused on fundamentals of security and do not prescribe specific types of products is accelerating the shift towards evidence-based security.

There are many other examples of cybersecurity frameworks and models that can help companies plan and implement sound security controls. Most recently, CIS introduced v2.0 of the CIS Community Defense Model which can be used to design, prioritize, implement, and improve an enterprise’s cybersecurity program.

Investors betting on evidence-based security

For tectonic industry shifts to become possible, investors need to believe in the approach and back up their beliefs with concrete actions. We have seen that in a case with evidence-based security, the belief is strong.

In April 2021, Tines raised $26M Series B for its no-code security automation platform. Then, in October 2021, SOC Prime landed $11M Series A to scale and accelerate the adoption of its marketplace that allows researchers to monetize their threat detection code to help security teams defend against cyberattacks. Shortly after, Panther Labs, a cloud-scale security analytics platform trusted by many of the world’s leading brands, announced $120 million in Series B funding with a unicorn valuation.

The funding trend has continued this year. In May 2022, LimaCharlie raised 5.45 million in seed funding led by Susa Ventures to accelerate its vision of bringing an engineering approach to cybersecurity through the Security Infrastructure as a Service (SIaaS) model. A month before, in April, Prelude raised $24M Series A to help organizations harden their cybersecurity defenses.

In several private conversations with investors, I’ve learned that many choose to back companies who take a new approach to security and increasingly adopt non-standard go-to-market strategies. This is significant because it affects the incentive structure that leads founders to create isolated, point-and-click products that solve one small use case: identify a small problem that could be solved by building a feature of an existing security product, raise capital, solve this problem, get acquired by a large company & become a feature of their bigger tool.

Notable by-products of shifting to evidence-based security

Focus on security fundamentals

Instead of getting locked into the thinking that “we need this next-gen magic tool that just works”, more and more security professionals are starting to think from the first principles. Start by understanding the crown jewels of your organization and by talking to people to gain a broad view of systems and processes. After that, establish observability (getting the telemetry from all sources — SaaS logs, cloud logs, endpoints, firewall, network, etc.), and set up the basic correlation. The idea of log aggregation is not new; all cloud providers have been producing audit logs for a long time. What is new is the understanding that security has moved far beyond endpoints.

Once you have full visibility into what’s happening in your organization, you can do something about it. You can move to response and automating manual tasks. Start by looking at what you are trying to protect, what you are protecting against, and how these two overlap (frameworks such as MITRE ATT&CK can be very helpful here). Based on the risk appetite, prioritize where you need to have coverage, and execute to establish that coverage.

By using detection & response logic transparently, continuously testing your security coverage against MITRE, and constantly expanding the list of behaviors you are able to detect in your environment, you will be able to move from hoping that a vendor will protect the organization, to knowing exactly what you are covered against, and what you need to work on.

Shift from analysts to engineers

We have all heard about the so-called talent shortage in the industry as cybersecurity needs millions of workers. These estimates are based on the needs we know about today, and I am confident the numbers are even higher as the adoption of new technologies leads to the creation of new attack vectors. We need people.

What is talked less about is the nature of the people we need. Security operation centers (SOC) are transforming; rooms of screens where tens of analysts monitor dashboards are being replaced with teams of engineers writing code to detect and respond to suspicious activity, automate processes, and eliminate manual tasks.

A deep understanding of attacker methodologies, tools, and techniques will always remain critical for defense teams. However, for those looking to grow, they are no longer enough: writing code will be critical. Cybersecurity is becoming more technical, and the lines between security and software engineering are blurring. This shift has already happened in FAANG companies and fast-growing Silicon Valley startups, and it will eventually trickle down to more traditional industries.

For security vendors, this means the need to adopt an engineering mindset. As security is transforming into a more technical discipline, the expectations about how security capabilities are delivered are starting to mirror those in software engineering. Companies are looking for API-first solutions designed for scale with everything as code (infrastructure as code, detections as code, policies as code, etc). Revenue models are shifting to transparent usage-based billing with predictable pricing, monthly invoicing, and no contracts to sign — a shift that has happened to developer tools in the past decade.

Test-driven, continuous security

We are seeing companies move towards adversary emulation, which is essentially a test-driven security similar to test-driven development that has been actively used for a few decades. Using Atomic Red Team, Prelude, or other components of the infrastructure, companies are now able to test their security coverage. The key is to run the tests continuously: twenty seconds after the detection is deployed, the environment will look different ( a new machine is spun off, etc.). It is no longer enough to have a reminder to run tests once a month or once a quarter — testing an organization’s defenses and security posture needs to be happening continuously. Penetration testing services are on the rise, and some companies go even further to ensure the strength of their defenses.

Changes in the way security products are marketed and sold

The generation of promise-based security vendors provides “magic” solutions that promise to do things like “stop breaches” or “prevent ransomware”. While products themselves are generally good, those blanket statements are laughable to experienced cybersecurity professionals. The definitive statements are marketing that is targeted at business level people that make purchasing decisions. The reality is that there is no 100% full-proof solution and that cybersecurity professionals employ a lot of risk management — “given the amount of risk we will use N resources to get a level of coverage that we feel satisfies the given risk profile”. Additionally, many security products are over-marketed for zero-days and advanced persistent threats (APT), and under-engineered for the threats these products will face in real life.

The new generation of evidence-based security vendors makes no promise of “magic” but instead provides pro-tools (and infrastructure) to cybersecurity professionals that have a mature understanding of the technological issues. A number of the startups taking this approach have built their whole go-to-market (GTM) strategy around this. They provide tools security professionals need in a way that lets them use them how they want with full transparency and they enjoy the experience so much they bring it back into their companies.

These technical people with a solid understanding of security do not like “fluffy” marketing or aggressive salespeople. Instead, they are looking for competent and clear messaging backed up by transparency (pricing, technical documentation, a community for help, etc.) and solid technical implementation.

Conclusions

Cybersecurity is a young and ever-evolving field. It wasn’t too long ago when being secure was synonymous with being compliant. Since then, we’ve seen that most companies that suffered massive breaches checked the compliance boxes. It wasn’t too long ago when being secure was synonymous with having an antivirus and a password manager before we’ve seen that these aren’t silver bullets either. Now, fewer and fewer companies still think that an “AI-powered next-gen EDR/EPP/AV/XDR/SIEM” will keep them safe. They probably won’t.

With security budgets rising, businesses are starting to ask for proof that the money is well spent. Boards see that there is no correlation between spend and protection as organizations with huge security spending are getting hacked. They are starting to demand proof, and this proof can only be provided if the company has control over its security posture. “We’ve implemented a vendor X who should take care of everything” is no longer an acceptable answer.

Push for meaningful metrics combined with the growing complexity of cybersecurity and increasing maturity of security professionals are some of the reasons we are seeing a shift from promise-based security to evidence-based security. Any large change requires infrastructure to support it across multiple dimensions — talent, vendor ecosystem, investment, government support, and education. As we have discussed before, each of these components has been evolving to provide a strong basis for the new approach in the industry: capabilities over products when it comes to the vendor market, skills over certifications when it comes to hiring, and others.

Cybersecurity isn’t going to get easier, but it will get more mature. Cybersecurity professionals will have a better understanding of fundamentals and a stronger ability to define the security posture in their organizations. Hopefully, it will lead to the reduction of cyber breaches, but only time will tell.

Further Reading

The following reports and articles provide a deeper dive into some of the trends discussed here.

Voice of the SOC Analyst report 2022 from Tines

State of threat detection & response from Panther

Detection as Code Innovation Report 2021 from SOC Prime

Evolution of cybersecurity and Security Infrastructure as a Service from Venture in Security (Ross’s blog)

Loved this and about to read more, so keep it up. :) I am curious about why cybersecurity tabletops (TTX) are not detailed as one of the best ways to measure and prove your defense spending has been worthwhile. Would love to chat if you have the time.