Investing in cybersecurity: a deep look at the challenges, opportunities, and tools for cyber-focused VCs

A comprehensive guide for investors specializing in cybersecurity, cybersecurity startup founders, and aspiring entrepreneurs

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Introduction and two main types of VCs investing in cybersecurity

While there are many types of actors that provide capital to cybersecurity ventures (private equity, angels, traditional financial institutions, corporate venture funds, etc.), in this article I would like to look at venture capital firms.

There are many ways to segment VCs - by fund size, stage, industry vertical, investment thesis, etc. For this discussion, I am interested in two types of venture capital firms:

Generalist VCs - those that invest in a broad range of segments, geographies, markets, etc. (e.g., global companies from different markets)

Specialist VCs - those that choose to specialize in a specific market (e.g., cybersecurity), industry sub-segment (e.g., compliance tech), geography (e.g., US), or an overlay of a few (e.g., seed-stage cybersecurity in Israel).

Amongst generalist VCs, most big players have a well-established practice in cybersecurity - Accel, Bessemer Venture Partners, Andreessen Horowitz, Sequoia, Sands Capital, and others. They have dedicated people focused exclusively on cybersecurity, making the nature of their cybersecurity investment as focused as specialist cybersecurity VC firms.

In the parts that follow, I will consider generalist VC firms with a dedicated cybersecurity-focused team to be the same as specialist VCs focused on cyber (I will be referring to both of them as cybersecurity-focused VCs). I will be describing other VCs as “generalist VCs” as they do not focus on cybersecurity.

Going into the article, I would like to make a statement that cyber investment is not a place for “tourists” or “part-timers”. Lots of things in security sound good but don’t sell, are based on questionable technology, or lack a unique value proposition. For an outsider, it’s easy to think that there is a value proposition where there isn’t one, and the other way around. Like with biotech, a person making investment decisions needs to have experience in the domain. I will explore some of the reasons for this phenomenon in the article.

As cybersecurity investing is a niche that requires specific talent, VCs focused on this space are generally happy to work together - referring startup founders to funds that might be a good fit based on their stage/thesis, and co-investing into deals.

VCs without a specific focus on cybersecurity tend to either stay away from this space, recognizing its complexity or go right in, sometimes seeing the hype of cyber & overpricing the company which can result in added difficulty when the startup needs to raise the next round.

The 2022 cybersecurity ecosystem map featuring 22 VCs, one investment bank, 13 corporate venture capital firms and 4 angel groups. Source: Global cybersecurity startup ecosystem map: a founder’s guide.

Cybersecurity as a recession-proof industry

Cybersecurity is an industry with cyclical interest - it stands out more during times when people believe bad things are happening, such as wars and military conflicts, political crises, recessions, and economic downturns. For example, in 2001 after 9/11, there was rapid growth in cybersecurity investing. Today, cybersecurity gets a lot of attention because of the Russian war against Ukraine.

Cybersecurity is remarkably resilient. So far, we have been seeing cybersecurity markets move in one direction, despite financial crises, recessions, and COVID lockdowns. It is generally hard for companies to justify cutting their security spending, which makes some experts observe that cybersecurity is a recession-proof industry.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, cybersecurity has been drawing more attention than usual. The biggest influx of capital came from growth investors who saw it as a way to diversify and expand their investments in SaaS and infrastructure offerings. With the recent economic downturn, valuations in SaaS have gone down. In cybersecurity, that has been the case for companies that aren’t performing as expected, but for those on track, the impact of the economic environment has been minimal. Cybersecurity founders are finding it easier to access capital compared to founders in other industries. However, cybersecurity funding in Q3 2022 is substantially down.

Select aspects of the global cyber VC market

US is the leading market for cybersecurity-focused VC activity, both in terms of the number of VCs and average check sizes, followed by Israel

United States

The growth of the cybersecurity startup ecosystem in the US has been happening hand in hand with the rise of cybersecurity-focused venture capital firms; from those that focus exclusively on cybersecurity (AllegisCyber Capital, Ten Eleven Ventures, and others) to those with a strong portfolio in cybersecurity and a team of people dedicated to the industry such as Sands Capital. I have previously counted at least 11 VCs with a heavy focus on cyber in the US.

In 2021, US-based cybersecurity firms led the way in funding, securing $17.4 billion in VC investment, compared to $6.9 billion in 2020.

Access to capital in the US is further amplified by the access to other resources available to cybersecurity startup founders. A decade ago, Maryland, a state that has the highest concentration of cybersecurity professionals in the world, had little tradition of building startups (no GTM, no strategy, no product expertise). It did, however, have a great pool of technical security professionals with many people coming from NSA, DISA, and U.S. Cyber Command. DataTribe, a cybersecurity foundry (a “package” of capital, industry connections, and startup growth experts), started 17 companies to date by combining the technical expertise available in Maryland with the Silicon Valley startup playbook.

Another important factor impacting the quality of the cybersecurity tech ecosystem is the role played by the government. In November 2021, the $1.2 trillion dollar Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act was signed by President Biden. It includes $1 billion for grants to improve state, local, tribal and territorial government cybersecurity. The US government can afford to invest more in cutting-edge cybersecurity research than many vendors combined. For that reason, the National Security Agency (NSA), Department of Defense (DOD), and other government institutions are acting as research and development shops for the cybersecurity industry, pumping millions of dollars into cybersecurity innovations. People in these institutions know well “where the puck is going to be” (where the threats are going to emerge), and this knowledge tends to disseminate within a few years across the broader industry. Years later, some of these ex-government professionals start their own companies with the mission of protecting people and organizations from threats they previously helped to create.

Israel

“While cyber makes up less than 5 percent of VC money received by US-based companies, more than 20 percent of venture investment in Israel have gone to the country’s cyber, according to Crunchbase data.” - TechCrunch

In 2021, Israeli cybersecurity startups received a historic high of $8.8 billion, driven by the increasing vulnerabilities during the pandemic. The country’s government has done a lot to foster the cybersecurity tech ecosystem in the country. In the same year, roughly one-third of all unicorns in cybersecurity was based in Israel. Israel has a mature ecosystem of cybersecurity-focused investors - from angel networks to VCs such as YL Ventures and Cyberstarts. A lot of Israeli seed firms will typically do Series A rounds with a US investor and move the founder to the US post-closing. I have counted over 5 VCs fully focused on cybersecurity in Israel.

Europe

US and Israeli investors are hesitant to invest in Europe, so European cyber is mostly funded by European VCs. Unlike the US and Israel, Europe hasn't had many big exits in cybersecurity, causing the fact that there aren’t many ex-founders with resources to re-invest into the growth of the regional cyber ecosystem. The situation, however, appears to be changing. Following Darktrace's successful IPO on the London Stock Exchange in 2021, Darktrace co-founder Dave Palmer joined Ten Eleven Ventures as a partner in 2022, opening the European office of the VC firm in the UK.

While the quality of many European startups is good, the market and the security budgets are smaller. In practical terms, it means that to get to the same revenue marker, instead of penetrating 5-10 companies, the startup needs to have their product adopted by 20-30, which extends the sales cycle and requires additional cost. This does not prevent European cybersecurity companies from growing globally, but to do so, they need to establish themselves in the US market. A great case in point is Tines - an Irish no-code automation platform aimed at security teams that recently raised $55 million in an extended Series B.

Source: CyberEdge 2021 CDR Report

For European companies, early-stage rounds make sense to raise in Europe (similarly for Israeli companies which get their initial investment in Israel). For later stages, if a company is successful, it will often be raising capital in the US, after which it will move the head office and the leadership team (at least in part) to the US. One thing to note is that most American venture firms will want to see the presence of the business in the US before they invest (typically Series B or C, and sometimes at the A stage).

The uniqueness of cybersecurity as an investment area

Several characteristics make cybersecurity rather unique from an investment standpoint.

Cybersecurity has an external force of innovation

The pace of innovation in cybersecurity is tied to two factors: tech innovation in general, and activity on the offensive side (commonly the nation-states). The actors on the offensive have the initiative and are often better motivated. This external force makes cybersecurity unique, as someone smart on the other side of the wire is actively trying to break into something a company is building or trying to defend.

Product cycles in security are short, and to get closer to innovation, it is important to be closer to the offense. What is discussed in offensive security circles today, will be discussed in defensive circles tomorrow. This is one of the reasons why it is hard to invest in cyber part-time: a cybersecurity investor needs to be a part of the security community, attend events to see what’s being talked about and stay on top of recent developments, from business to technology while also understanding what the threat actors are doing. It is hard to imagine someone being successful in the industry by simply sitting on Sand Hill Road, going through the pitches via Zoom, reading Gartner, and writing checks.

The quality of what is bought and sold is not known

As Mark McGovern of Sands Capital pointed out, what makes cyber security particularly unusual is that the quality of what is being bought and sold is unknown. A team buying a security product has no way to be certain that in critical moments, the product will do what it promises to do. This is especially true for products that fall under the bucket of promise-based tools. This uncertainty makes switching vendors hard; with most firms not having the ability to evaluate tools in-house, firms such as Gartner hold a lot of power and are capable of greatly influencing purchasing decisions.

The small supply of talent

To start a cybersecurity company, one generally needs to have a solid, hands-on experience in the field. As the industry itself is new, deeply technical, and fast-changing, the pool of people capable of identifying and successfully tackling a well-defined problem area is relatively small. Cybersecurity is not something most people can accidentally get exposed to, quickly see an opportunity, and can act on it.

While the supply of technical talent is small, the percentage of people who are entrepreneurial in addition to being technical is even smaller. There are not a lot of people who can build a cybersecurity company despite a big demand and a readiness of VCs to pour the capital in the field. That is why it is common to see repeat entrepreneurs with a strong track of success in cybersecurity.

Innovation is more often acquired, not built in house

While acquisitions aren’t by any means unique to cybersecurity, there are some unique circumstances worth calling out.

Cybersecurity innovation is often acquired, not developed in-house. This makes cybersecurity somewhat similar to biotech & pharmaceutical industries which tend to have highly specialized firms focusing on different drugs and high M&A activity.

Cyber threats move incredibly quickly (vulnerabilities are being discovered and exploited, cyber warfare is being developed daily, and new attack surfaces emerge with the introduction of new technologies), and incumbents have a tough time keeping up. Innovating on multiple fronts simultaneously is very hard, especially because each area of security tends to require very deep, specialized expertise. When everything you do is related to Windows security, it’s hard to easily accumulate expertise in the area of Android or AI security and come up with innovations in new areas.

The high frequency of startup acquisitions greatly affects the startup success rate. While it is hard to compute the failure rate of startups within the industry, anecdotal evidence and personal observations show that the number of companies going out of business is lower than in other industries.

Once a cybersecurity startup has identified a problem and built a solution, or better yet - attracted at least a small number of paying customers, it has a higher potential to get acquired compared to players in other industries. Founders may exit to a larger company even if they fail to achieve any traction as a product acquisition or “acquihire”. Incumbents need to expand into new markets and find the best talent, and M&A activity gives them a pipeline to achieve both of these objectives.

While VCs should be focusing on maximizing the upside and picking the companies with potential to win instead of minimizing the downside, for VC firms with the right expertise, cybersecurity investing can be more predictable and less risky than investing in other industries.

Founders may bootstrap their product companies by offering services

Technical cybersecurity founders often start a cybersecurity consulting/services company first and then spin off a product later. This enables them to slowly grow from a single self-employed person shop into an established consultancy, build reputation in the industry, identify a problem worth tackling, and bootstrap building an MVP, a BETA version of the product, or even a full product by reinvesting the profits from their consultancy. Raising capital is not a necessity for service providers as Security Operations Center (SOC) and Incident Response (IR) services, to name a few, do not require large capital upfront. This can be a great approach for founders enabling them to avoid early dilution before they build a product and find the initial product-market fit.

There are, however, challenges with this approach. From an investment perspective, service companies generally result in substantially lower multiples than their product counterparts, which also makes them less attractive to investors. This is generally because of the low scalability of the service-based companies (the revenue is directly dependent on the hours of service, margins are lower, and the economies of scale are harder to achieve). What’s more important is that a lot of the learnings and experience running a consultancy do not translate well into building a product, resulting in a learning curve for founders that they may not be able to successfully bridge.

Blitzscaling is not (generally) an option

Cybersecurity is not an industry that has seen many companies succeed with the blitzscaling. Reid Hoffman and Chris Yeh define blitzscaling as a “specific set of practices for igniting and managing dizzying growth; an accelerated path to the stage in a startup's life-cycle where the most value is created. It prioritizes speed over efficiency in an environment of uncertainty, and allows a company to go from "startup" to "scaleup" at a furious pace that captures the market.” While blitzscaling is a dream of many founders and VCs, cybersecurity is poorly positioned for this strategy as it heavily relies on trust, and trust, in turn, is built over time, not overnight simply by hiring 300 sales/marketing professionals. Security leaders take their time before scrupulously evaluating new products and approaches to security, relying on industry leaders, analysts, testimonials from reference customers, and the company’s “street cred”, among other factors.

While cybersecurity is not well positioned for blitzscaling, it does not mean that blitzscaling in cyber isn’t possible. One of the companies that defied this limitation is Wiz which hit $100M ARR in 18 months becoming the fastest-growing software company.

Wiz founders targeted a broad and fast-growing market (everyone who needed the cloud), understood the use case, and had the right product attributes. They avoided requiring customers to install yet another agent, thereby reducing the obstacles to adoption. Lastly, they made it possible for customers to experience value in minutes - something that I, as an operator with a background in product, find fascinating.

Buyers are overwhelmed with undifferentiated options

There are over 7000 or 8000 cybersecurity vendors, and more are created daily. CISOs and security leaders are overwhelmed with the number of options, of which most offer the same, highly undifferentiated, and commoditized capabilities.

At the same time, awareness about the need for cybersecurity is growing, which, in turn, comes with increased budgets and leads to security becoming a board-level concern. All this presents a tremendous opportunity for savvy founders capable of crafting and executing effective go-to-market strategies.

Advantages and disadvantages of staying cyber-focused for VCs

Working with cybersecurity-focused VCs presents founders with several advantages.

First of all, investors that specialize in cybersecurity generally come from the industry (ex-founders or ex-cybersecurity practitioners) which gives them the experience to understand what the startup actually does. This is very important, especially at the earlier stages where there are not many numbers yet, just a vision, a team, and maybe an early version of the product. There are many cases when a generalist VC would need to ask some very basic questions and drag the decision-making process for a long time as they don’t have the in-house expertise to evaluate the company; a VC specializing in cyber can make their investment decisions much quicker.

Second, cybersecurity-focused VCs know the market and have great relationships with other specialist VCs, security leaders, and industry insiders. This enables them to broker connections to potential customers, partners, advisors, and investors who can participate in the next rounds.

Lastly, cyber VCs see comparable products and ideas every day, making it easier for them to spot patterns, understand the competitive dynamics, provide advice and recommend resources to founders that they would not be able to access otherwise.

In general, cybersecurity-focused VCs are much more likely to deliver on the promise of adding real value beyond simply investing capital - something that enables cybersecurity companies to accelerate their growth trajectory faster and without repeating the same mistakes that other founders in the industry have already been through.

This industry focus, on the other hand, can also be a liability as it limits the ability of VCs to see what is happening in other markets, and how it may affect their portfolio companies. For example, investors focused on the enterprise may discount the importance of good user experience which, having emerged in the B2C space, is now changing how people expect to consume B2B offerings as well. There is a lot to be gained from being a generalist and looking beyond what is familiar. While technical innovation comes from being deeply immersed in one field, business model innovation generally stems from the ability to see across the boundaries of industries and market segments.

Making sense of the cybersecurity industry: tools for untangling the complexity

The need to build mental models around cybersecurity

Regardless if you are an industry veteran with 20 years of cybersecurity experience, a recent graduate, or a VC associate, we can all agree that cybersecurity is a complex and face-paced field. If you were to google “cybersecurity news”, you will see a flood of everything under the sun - new zero-day vulnerabilities, ransomware investigations, data breaches, a myriad of confusing marketing claims, and a sea of abbreviations. It is simply not possible for anyone to make sense of this complexity by simply going through the sources.

Industry analysts don’t make the task much easier either: at any given time, you can read praise to the new buzzword heard at the RSA Conference (in 2022, it was arguable Zero Trust and XDR), analysis of attacks by nation-states, complaints about un-differentiated vendor market, and predictions about the new type of tools needed to solve most problems. This game of “what tool do we need'' can get intense. There are SSPM, CSPM, EDR, XDR, NDR, SASE, DLP, ZTNA, SDP, NGFV, IDS, IPS, IAM, VPN, SSO, UBA, UEBA, WAF, FWaaS, MDR, CASB, SIEM, SOAR, XSOAR, AV, XSIAM, and many more; the list of abbreviations is never-ending.

To make sense of this cacophony, a methodical way to organize information is needed. Instead of prescribing solutions, let’s look at the problem from the first principles - break it down into components and tackle them one by one.

For practitioners, the problem they were looking to solve for years can be summarized with a question - “What are the tools and techniques attackers use to accomplish their goals? How well are we doing at detecting known adversary behavior?”. This approach of taking a systemic view of what is happening in the industry has led to the introduction of the MITRE ATT&CK® framework in 2013. MITRE ATT&CK® is a “globally-accessible knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques based on real-world observations. The ATT&CK knowledge base is used as a foundation for the development of specific threat models and methodologies in the private sector, in government, and in the cybersecurity product and service community”.

MITRE ATT&CK® framework has codified the security knowledge for security leaders and practitioners, setting the stage for the maturation of cybersecurity as a discipline.

MITRE ATT&CK® framework is most useful for practitioners. What it doesn’t do is provide a bird-eye view into the composition of the market helping investors to make sense of security product categories, identify underserved market segments, assess directions for market consolidation, and anticipate what new market categories will be created.

Fundamentally, the questions investors are asking are:

What new technologies are emerging that will need to be secured?

What new adversary behaviors are we seeing today and how are they being addressed by the existing tooling?

What new technologies are emerging in the cybersecurity space?

What market categories are already saturated, and which are well positioned for new entrants?

How do I ensure that new startups we are considering investing in will not compete with companies in our existing portfolio?

How to analyze the inherently complex cybersecurity landscape and anticipate vendor movements into different market sub-segments?

Unfortunately, the so-called Gartner Magic Quadrant offers little help in answering these questions, as do so common in the industry “market maps” - collections of company logos organized by what existing abbreviation they fall under.

Fortunately, there are tools well-suited to help find answers to at least some of these fundamental questions.

The Gartner Hype Cycle

Security has always been a reactive discipline responding to each new technique by attackers. Internet security became a thing after someone started to interfere with the network. IoT security became a thing after someone started to break into IoT devices. The list can go on and on, but fundamentally the cycle repeats itself with the introduction of new technologies: there is a tech revolution, then a new solution is widely adopted, then it turns into an attack vector, and cybersecurity comes into play to prevent cyber attacks. There is commonly a few year gap between the growth of new technology and the rise of security solutions that protect it; most recently this has been the case for areas such as API security, cloud security, and container security. As cybersecurity follows new technologies, it means that to anticipate new tech, we need to look at what new technologies are emerging that will need to be secured.

The Gartner Hype Cycle is a graphical presentation by Gartner that intends to represent the maturity, adoption, and social application of specific technologies. While it is by no means objective, it does present a decent view of the evolution of emerging technologies.

The Gartner Hype Cycle is great for answering the question “What new technologies are emerging that will need to be secured?”.

The 2021 and 2022 Gartner Hype Cycle for emerging technologies look as follows.

As each new technology introduces new vulnerabilities, cybersecurity entrepreneurs and investors can use the Gartner Hype Cycle charts to anticipate new technologies in need of security.

This format can be used for VCs to keep track of different sectors and technologies they are looking in, as new technologies tend to follow the same path of progress.

The MITRE ATT&CK® framework

Many sources can help you get a deeper understanding of what cyber threat groups are active, which specific techniques or software programs might be used to target different kinds of businesses, and how security teams currently detect and mitigate against adversarial techniques. The easiest and the most comprehensive one is to look at the previously mentioned MITRE ATT&CK® framework - a tool that offers information about the tactics, techniques, and tools that cyber criminals employ to infiltrate targeted networks and achieve their goals.

The MITRE ATT&CK® framework is great for answering the question “What adversary behaviors are we seeing today and how are they being addressed by the existing tooling?”.

The MITRE framework is very large and very complex, so it may not be of immediate use to those looking for a broader view of the space. However, it can provide a deeper level of context often missing from the more high-level analysis.

Source: The MITRE Corporation

The Cyber Defense Matrix

Until recently, I did not know of any tool that would help cybersecurity investors to rationalize cyber technologies, and find investment opportunities. Then, one time I was talking to Bryson Bort, founder of SCYTHE and GRIMM, who recommended the Cyber Defense Matrix by Sounil Yu. This incredibly short yet important book introduced me to the best tool I have found to make sense of the industry plagued with buzzwords, marketing fluff, and magic offerings by the vendors - the Cyber Defense Matrix.

Cyber Defense Matrix helps investors to look beyond marketing buzzwords and meaningless claims, and instead focus on what any product or market category actually does. I highly recommend Sounil’s book to anyone involved in making investment decisions - whether they are working in venture capital, public markets, private equity, angel investing, or any other area. My goal in this article is to introduce the matrix, not to explain in detail how to use it as that is beyond the reasonable word count for an already long writeup.

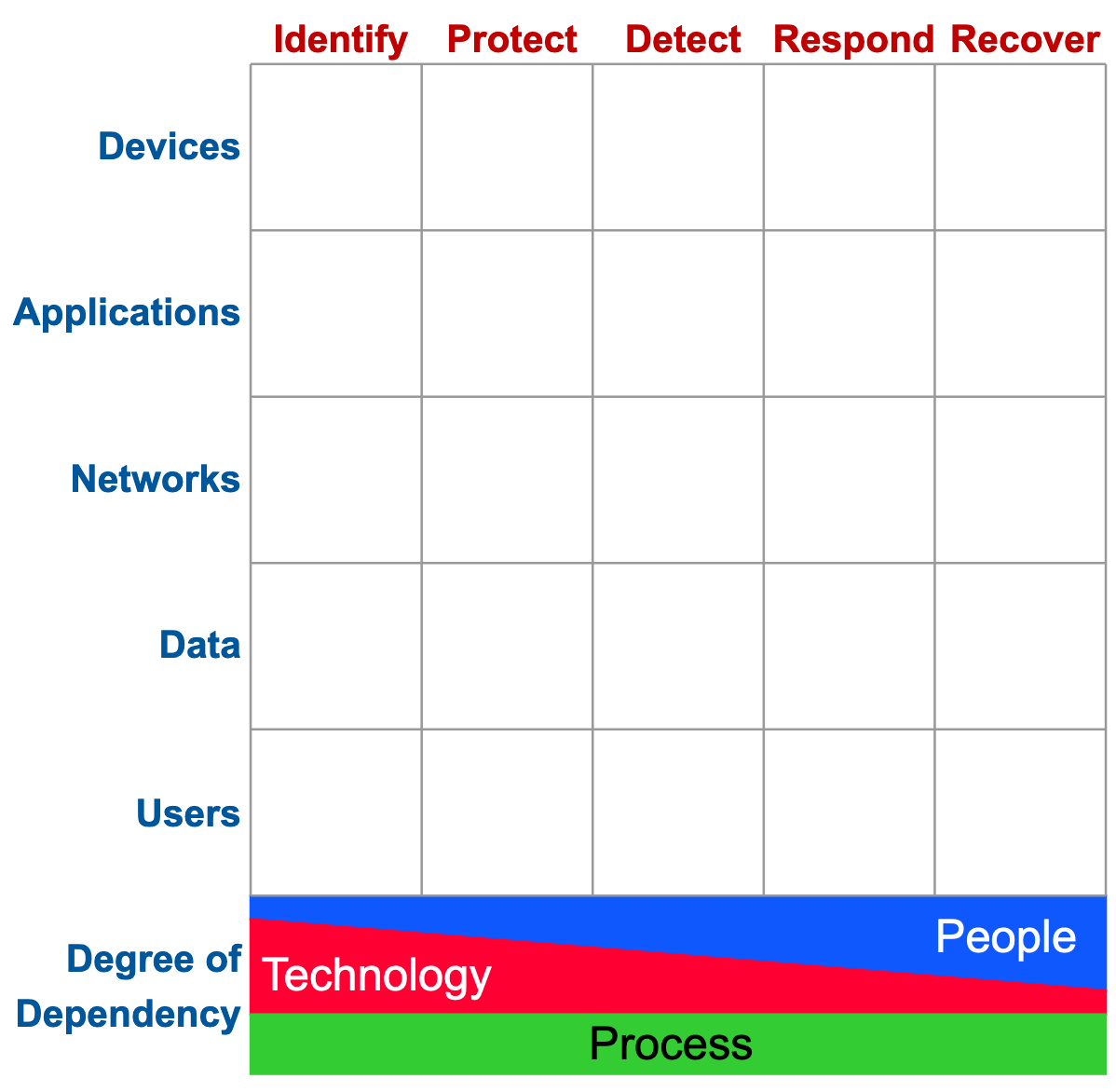

The Cyber Defense Matrix is organized in a way that all individual boxes are mutually exclusive (one product can only fit into one box) while combined together are collectively exhaustive (capture all available options). The framework is visualized as a 5 x 5 table with cybersecurity functions (pre-breach - identify, protect; post-breach - detect, respond, recover) as columns, and asset types (devices, networks, apps, data, and users) as rows. There are several important rules and nuances when it comes to constructing it, but addressing them is out of scope of this article.

Each vendor can be mapped to a specific box on the Cyber Defense Matrix. Source: Sounil Yu

Unlike traditional market maps, the Cyber Defense Matrix helps organize product categories based on what they do. Below is an example of what I think that could look like.

As we rarely see vendors capable of performing the same function across all asset classes, looking at the industry from this perspective makes it easy to see the innovation potential. If we know that a capability exists which allows us to do a complete inventory of one asset class (say, devices), we may realize that the ability to do the same in other asset classes (say, data) is not yet there. As Sounil highlights in his book, “some of these gaps become particularly obvious when a new subclass of asset (e.g., IoT, APIs, 5G, etc.) emerges in our digital environment. With each new subclass of asset, we often follow the same pattern of capability needs and development. For example, when IoT or SCADA security became a major concern, the first capabilities were focused on inventory and visibility. Over time, other capabilities become available in the marketplace”.

Vendor movement, both horizontally and vertically across the matrix, is nuanced. Many vendors start in Identify section and move vertically to other assets, creating solutions that can work across multiple asset categories, or horizontally to Protect to cover a full spectrum of jobs to be done around one asset type. Because of the unique defense mechanisms required for each asset class, it is less common to see vendors moving vertically in Protect.

The Cyber Defense Matrix makes it easy to draw analogies across different market sub-segments. For example, mapping out the existing technologies on the Cyber Defense Matrix makes it possible to anticipate new categories that will be emerging in the industry. In his book, Sounil illustrates this by showing how mapping the zero trust access proxy to the right boxes (Zero trust network access (ZTNA) to Network - Protect, Zero trust application access (ZTAA) to Application - Protect, and Zero trust device access to Device - Protect) reveals the potential opportunity for a Data-centric access proxy, something we’re starting to see with the emergence of Data access security brokers (DASB).

The Cyber Defense Matrix is not a magic tool capable of providing answers to any question, but a way to structure thinking, see patterns and anticipate market shifts. Some of the questions that can be answered by leveraging the Cyber Defense Matrix include:

What new technologies are emerging in the cybersecurity space?

What market categories are already saturated, and which are well positioned for new entrants?

How do I ensure that new startups we are considering investing in will not compete with companies in our existing portfolio?

How to analyze the inherently complex cybersecurity landscape and anticipate vendor movements into different market sub-segments?

In a market saturated with buzzwords and two-to-five-letter abbreviations, Sounil’s Cyber Defense Matrix is a must-have tool for any investor looking to build a comprehensive view of the market. I must add that I am not in any way affiliated with the author or the publisher, but rather a big fan.

Closing thoughts

Cybersecurity is a growing field, and despite the inherent complexity, it can be a great area for investors with a solid understanding of the industry. There is a multitude of changes happening at once, such as the adoption of product-led growth and the move from promise-based to evidence-based security. Being able to spot these trends, connect with founders, and understand the threat vectors and how they are being exploited is critical to developing the ability to pick companies with the potential to win.

Cybersecurity is not a place for tourists and those looking for quick returns but for investors willing to be patient and put in the work it most certainly presents great potential. All this explains the ever-growing number of investors entering the space, and with the global cybersecurity market size expected to grow from an estimated value of USD 173.5 billion in 2022 to USD 266.2 billion by 2027, there is most definitely room for more players.

Credits

Thank you to the leading cybersecurity investors who were so generous to share their thoughts and experiences as I was working on this piece: Mark McGovern of Sands Capital, Alex Doll and Kaiti Delaney of Ten Eleven Ventures, Bob Ackerman of AllegisCyber Capital, Reinout vander Meulen of TIIN Capital B.V., and Stav Pischits of Cyber Club London among others. A big thanks to Bryson Bort, founder of SCYTHE and GRIMM, for recommending the Cyber Defense Matrix by Sounil Yu, and to Sounil for creating such a great organized way to make sense of the cybersecurity industry. Opinions and conclusions are my own.