How hands-on security practitioners are defining the future of the industry

A brief look at the factors that enable security practitioners to define the trajectory of the cybersecurity

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Regular readers of Venture in Security know that among the variety of topics I write about, there are three I keep coming back to over and over again, namely:

the role of security practitioners in the industry

product-led growth and how it fits as one of the go-to-market strategies in security

maturation of the industry and its move from promise-based to evidence-based security

Over the past several weeks, I’ve been passionately discussing these and many other ideas with Caleb Sima, who like myself, is a big believer that the industry is evolving and becoming more practitioner-focused. In this issue of Venture in Security, I would like to explain how the three trends come together and why the future of security is rapidly changing.

This post is brought to you by… The Blue Team Con.

Defenders! Blue Team Con is Coming to Chicago August 25-27 — Register Now!

Registration is now open for Blue Team Con, the premier defense-oriented cybersecurity conference. Join us for a diverse and inclusive platform exclusively focused on sharing information amongst defenders and protectors of organizations, with more than 30 talks by expert speakers from Microsoft, Meta, CrowdStrike, AWS, DHS and more. New this year is an optional training day featuring exclusive in-depth sessions on key issues. Plus topical villages, a CTF challenge and more. Earn over 21 CPEs!

Blue Team Con runs August 26 and 27 at the Fairmont Chicago Hotel, with training sessions on August 25. More information and tickets at BlueTeamCon.com.

The three stages of security

To understand why the voice of security practitioners is becoming louder, it’s worth briefly reflecting back on the history of the industry. Cybersecurity originated in communities of hackers, smart enthusiasts tinkering with technology, looking for ways to understand how the code works, subverting it into doing something it wasn’t originally designed to do, and most importantly collaborating and sharing their knowledge for free. While few listened to what early computer enthusiasts had to say, and we as a society ignored the warnings about Internet safety, it soon became clear that security is multi-faceted and complex.

This is where commercial vendors entered the picture. Some, started by passionate practitioners driven to improve the industry, were looking to build technical solutions to real-world problems, while many others were driven by the desire to capitalize on fear and confusion in pursuit of quick profits. During this time, hundreds and thousands of salespeople were hired, trained, and set with sky-high quotas to push snake oil solutions that “guarantee security, stop 100% zero days and APTs, cure ransomware, and prevent all attacks before they happen”. Buyers - either business people with no understanding of security or IT leaders with too much on their plate and few resources, had no choice but to trust that these tools would keep them safe.

With time, more and more businesses started to realize that security is a real need and hired dedicated leaders to own the function, namely Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs) and Chief Security Officers (CSOs). Unfortunately, most organizations didn’t provide newly hired security leaders with enough resources to implement their vision, so they had to do a lot with little. Worse yet, because the knowledge required to be effective at security is only accessible to a small percentage of organizations with solid budgets, vendors become the “experts”. All this has forced less fortunate organizations to fully rely on vendors, and those building security products got to decide what their customers needed.

This reality is now changing. More and more security leaders can get the budget to hire dedicated, hands-on security practitioners, or to partner with respected technical consultancies and service providers that bring solid domain expertise to the table. In these circumstances, CISOs are surrounding themselves with highly specialized domain experts - security engineers, architects, detection engineers, analysts, and the like. Companies that choose to engage security consultancies to help define their strategies, also notice that it’s no longer the MBA grads with PowerPoint slides, but experienced security practitioners who provide advice.

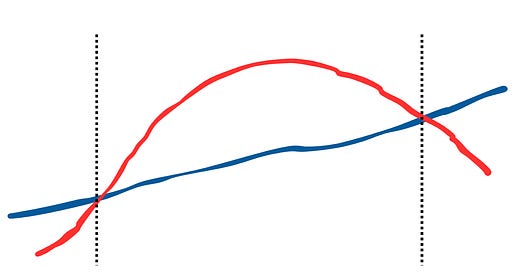

If we were to graphically display this evolution, it becomes clear that the security industry went through three stages of development:

The origins - the time when security practitioners had a voice even though few people and organizations listened.

The vendor era - the time when security vendors dictated what companies needed, and sold magic tools to stop any threat (buyers lacked knowledge and resources to do anything about it)

The practitioner era - the time when security practitioners in the enterprise or offering services through managed security service providers (MSSPs) and technical consultancies access the capabilities they need from vendors they trust

The rise and the ever-growing role of security practitioners

For a new field to emerge and become a profession, supportive infrastructure must be established - schools, professional standards, industry conferences, specialized recruitment firms, and the like. What we are seeing today, however, isn’t simply the rise of cybersecurity as a craft, but the rise of security as an engineering profession.

More and more security practitioners are sharing their knowledge and experiences in blogs (take Zack’s Detection Engineering), newsletters (think tl;dr sec), podcasts (such as the Cloud Security Podcast), and at industry conferences (such as the Blue Team Con). More and more of them are publishing books (take the recently released Software Transparency by Chris Hughes and Tony Turner), and teaching hands-on, practical classes such as those by SANS Institute, the pay-what-you-can Antisyphon Training, or Black Hat training. The rise and growth of regional BSides all over the world as well as various capture the flag (CTF) competitions are great testaments of the maturation of the security community. All this effort compounds and makes the voices of those doing the work, hands, on the keyboard, more and more powerful.

Security professionals are becoming critical to securing their organizations and advancing the practice, and they are also critical to how buying decisions are made in the industry: every day, their voice matters more and more. The time when company execs would attend tens of demos, go to dinners with vendors and negotiate five-year-long contracts is going away. Today, CISOs have too much on their plate - they are focused on defining the security strategy, growing teams, building relationships with other departments, working with boards and peers from the leadership, and other high-level matters. More and more security leaders are looking for ways to build high-performing teams, capable of assessing the needs of the organization and evaluating the tools that can solve those needs.

While product leaders and marketers are arguing whether or not product-led growth is going to transform the way security products are purchased, more and more CISOs are starting to delegate tool evaluation to people on their teams. While security leaders are and will continue to be the approvers of the buying decisions and the owners of the budget, the initial evaluation of tools and proof of value is coming from those doing the work. This makes sense since technical individual contributors are keeping track of emerging threats, continuously testing new approaches in their home labs, and evaluating new products. Another reason for delegating the tool evaluation to practitioners is the need to build empowered security teams. Similar to how software development has evolved from top-down directives to enabling individual engineers to own their work, security teams are inevitably going to change the way the work is structured and distributed. Lastly, security leaders are drowning in spam and never-ending requests from vendors to “get a demo”. Instead of triaging vendor requests and deciding whom to have a call with, it’s wiser to start by soliciting the ideas from the team, and deciding whom to talk to and what approaches to evaluate.

The role of security practitioners in shaping cybersecurity innovation

Security practitioners are the defining factor in the direction of cybersecurity innovation.

First and foremost, the overwhelming majority of successful cybersecurity startups are built by security practitioners. As previously discussed,

“Unlike in some other industries where an outsider can find an opportunity and act on it, in cybersecurity, most of the innovation is so technical and close to the metal that it would be very hard for someone without deep domain expertise to make sense of it. This does not, however, mean that a successful founder must be an engineer: what’s important is that they can understand the problem, navigate the dynamics of the industry, and be perceived as credible to the buyers and investors.

These domain knowledge, credibility, and connections can be achieved in several ways, including by being a security professional, a security leader, by serving in a cyber-focused role in the military, and by helping build another cybersecurity company. Founders of most successful cybersecurity companies tend to have different combinations of these backgrounds, for instance:

George Kurtz, the co-founder, and CEO of CrowdStrike, was previously the founder of Foundstone and chief technology officer of McAfee

Jack Naglieri, founder & CEO of Panther, was a security engineer at Airbnb

Oz Golan, co-founder & CEO at Noname Security, was a developer and security researcher at Israeli Defense Forces

It is common for security founders to spend a substantial amount of time in their segment before starting a company. This makes intuitive sense as for building SIEM 2.0, founders must know SIEM 1.0 deeply (ideally they would have worked on the team that built it). It’s statistically unlikely that someone new to the space can just come up with a great idea that accounts for all the nuances and inherent complexity the industry comes with, and execute it.” - Source: On a hunt for successful cybersecurity startups and unicorn founders

Second, security practitioners are the ones who are tracking new technologies, new attack vectors, and new threats when they are just emerging. The significance of this fact is hard to overstate: CISOs have so many problems on their plate, that they don’t have any time (and often - interest) to read technical research or attend Defcon sessions. By the time a new attack vector becomes a CISO-level concern, it’s already a business problem that needs to be tackled; for insights about what new technologies are coming, we should be going to hands-on security practitioners instead. To put it simply, CISOs can answer the question “Will my organization pay for X today”, but not “What new threats and technologies are being developed today that will become relevant 5 years from now”.

The fact that security practitioners are so close to the metal makes them critical when it comes to evaluating potential investments. As security is becoming more technically complex, traditional investors are struggling to evaluate ideas and solutions of the future, often funding tools that make big promises but don’t solve real problems. This is no surprise as to make sense of all the complexity, one must live and breathe cybersecurity, fully immersing themselves in the space. Cyber-focused VCs are a big step forward as, unlike “tourists”, they understand the nuances of the space and know what kind of support their portfolio companies need. However, they are not as close to real innovation as security practitioners who spend their weekends and evenings learning about new ideas, testing new tools and approaches in their home labs, contributing to great open source projects, and building their own tooling.

What this means is that security practitioners can:

help investors understand what tools and ideas are worth funding,

help startups validate problems and decide what direction to pursue, and

help entrepreneurs validate if the solution they built is solving a painful problem

Closing thoughts

Cybersecurity has always been late to adopt innovation, whether we are talking about the cloud, data lakes, infrastructure-as-code, or any other new approach in technology. The same is true for other aspects: it took over a decade for companies to establish a CISO role, and we are still fighting for security to be seen as a core part of the organization.

Even though it takes longer than we would like it to, evolution is inevitable. The people who are testing new tools, presenting at industry conferences, evaluating up-and-coming startups, advising founders, and learning about new attack vectors, are tomorrow’s security leaders, innovators, entrepreneurs, and investors. As more industry players realize it, we will see more focus on building practitioner-focused products, more community managers and sales engineers instead of spam, and business development representatives (BDRs) with no industry experience. I have a high degree of conviction that the future of security is bright and that it will look radically different from what we have today.

Ross, thank you very much for your valuable time to write and share deep, intelligent and cristal clear information.

I’m starting a journey in the cybersecurity industry in Mexico and your article perfectly describes todays CSO’s and CISO’s needs in order to face todays and future’s cybersecurity challenges.

Cheers

Joseph Liberman

Great stuff as always, Ross. While the work of the practitioner has become more complex, there is a need to make the lingua franca of security more accessible. In doing so security can elevate its role to its rightful position among business leaders who are often looking for a way to understand risks in simpler business terms.