Cybersecurity is not a market for lemons. It is a market for silver bullets.

In collaboration with Mayank Dhiman, Head of Security Engineering at Notion, we are looking into the reasons why security is not at all a market for lemons; instead, it is a market for silver bullets.

There is a lot of talk in the industry that security is a market where one side (namely, the security vendors) has substantially more information than the other (the buyers). This is often referred to as a market for lemons.

In this piece, in collaboration with Mayank Dhiman, Head of Security Engineering at Notion, we are looking into the reasons why security is not at all a market for lemons; instead, it is a market for silver bullets. Neither Mayank nor I didn’t come up with this idea on our own. Our article is centered around the analysis of an excellent essay written by Ian Grigg back in 2008 titled “The Market for Silver Bullets”. Since we connect our own ideas to those expressed in Ian’s article, please assume that anything not listed in quotations is our perspective and not that of Ian.

Ian’s essay is a must-read for anyone trying to understand the dynamics of cybersecurity on a deeper level, and we hope this article will inspire many people in the industry to give “The Market for Silver Bullets” a read.

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Over 2,260 copies of my best selling book “Cyber for Builders: The Essential Guide to Building a Cybersecurity Startup” have been delivered by Amazon so far. This book is unique as it talks about building cybersecurity startups. It is intended for current and aspiring cybersecurity startup founders, security practitioners, marketing and sales teams, product managers, investors, software developers, industry analysts, and others who are building the future of cybersecurity or interested in learning how to do it.

The state of the cybersecurity market

The tragedy of security

“You're proposing to build a box with a light on top of it. The light is supposed to go off when you carry the box into a room that has a Unicorn in it. How do you show that it works?” - Gene Spafford, as quoted in “The Market for Silver Bullets” by Ian Grigg.

We hope you find this quote as funny as we did. It highlights the impossibility of testing security solutions. This is the real tragedy of security – there is no easy way to tell the difference between sheer incompetence and sheer luck. If we didn’t get breached today, was that because the people, processes, and tools were effective and did their jobs, or did we just get lucky?

Every day, security leaders are approached by tens of different vendors claiming that they have found a way to prevent a new breed of attacks that are “very important” yet nobody else can detect them equally well because of some “secret sauce” this specific startup has developed. Vendors pitch their solutions as magical tools that can solve all of your cybersecurity problems – like a silver bullet that is supposed to work against werewolves, vampires, witches, or other supernatural beings. CISOs buy such tools, deploy them in their environments, and then are left wondering: if the product doesn’t produce any alerts, does it mean that nobody is using this new advanced attack vector against the company, or is the tool simply not working?

There is no way to reliably test security solutions

In “The Market for Silver Bullets”, Ian draws parallels between testing burglar alarms and testing security tools and argues that “In the business of security, the attacker is not a party to our testing procedure. Even though the attacker plays within the game, he is an active party; he is not an unbiased, rules-based agent that permits himself to follow statistical patterns. He deliberately attempts to pervert our security, and intends to cause the costs that we are hoping to avoid. As such, he is unimpressed with our efforts and seeks the gaps in them; he wins when we lose. Any test by one burglar will not find all those gaps, so even a real burglary is not a good predictor of any other event of distinct characteristics”.

It has been over 15 years since Ian’s article came out, but we haven’t found a good way to test cybersecurity products, and it’s not for the lack of trying. Venture in Security has previously discussed the need to move from promise-based to evidence-based security, but the truth is that this shift is going much slower than many people would hope.

To our credit as an industry, we’ve come up with the MITRE ATT&CK framework and operationalized it through tools such as Atomic Red Team and Prelude. We’ve found a way to compare different tools, even if not very well. Most of these advancements, however, haven’t been long-lasting because of what’s known as Goodhart's law - an adage which states that as soon as you publish a metric, it ceases to be a good metric because now everyone will try to optimize for that metric (or game the metric, depending on how you view it). Vendors can now optimize their tools to perform better at such tests, without improving the overall efficacy/effectiveness of their tools.

We went as far as to design product categories such as breach and attack simulation, adversary emulation, and continuous pentesting to try and find ways to test our security coverage. And yet, despite all this effort, there is no reliable way of verifying if one vendor’s security coverage is better than the other’s because there is simply no way to simulate all possible ways to bypass an organization’s defenses. By their very nature, attackers are creative and highly motivated to succeed and find the path of least resistance (much more than pentesters and breach and attack simulation tools would).

Buyers lack information to make informed decisions

In his article, Ian lists testimonials from people who make it clear that buyers lack information to make buying decisions. One person states that “ ... managers often buy products and services which they know to be suboptimal or even defective, but which are from big name suppliers. This is known to minimize the likelihood of getting fired when things go wrong. Corporate lawyers don't condemn this as fraud, but praise it as "due diligence". Another says “I go to security conferences where we all sit around puzzling about what kind of metrics to use for measuring the results of security programs”. These words written many years ago still ring true today. It is both bewildering and sad to realize that little has changed despite all the frustrations, discussions, and determination to find answers.

Not only do we lack information to make informed buying decisions, but we are also struggling to establish reliable metrics to justify security investments. Are more “findings” produced by a tool a good thing or a bad thing? Is a company that just invested in a new tool more secure than it was before? What does that mean in probabilistic or dollar terms? It feels like we are just guessing. There are credible attempts to quantify cyber risk but as of right now, it’s often hard to say where the science of these attempts ends, and where astrology begins.

Cybersecurity is not a market for lemons. It is a market for silver bullets.

Cybersecurity is not a market for lemons

The market where sellers are much better informed than buyers about the quality of the product or service they are selling is often referred to as a market for lemons. The term gained popularity after George A. Akerlof and Joseph E. Stiglitz won the Nobel Prize for Economics for establishing the theory of markets with asymmetric information. In 2007, Bruce Schneier wrote an article titled “A Security Market for Lemons” where he argued that cybersecurity is a perfect example of such a market. This thesis gained steam and since then, many others have added their perspectives to the collective thought, including Omer Singer in his great blog “Omer on Security”.

While it is tempting to assume that there is some kind of a conspiracy where security vendors are purposely concealing the information from security leaders and practitioners, that may not at all be the case. What if sellers don’t know any more about the products they are selling than the buyers they are selling them to? In “The Market for Silver Bullets”, the author argues that “It is a failure of logic to suggest that the buyer's lack of information means that the seller has that information. If sellers are indeed peddling goods labelled as security goods for purposes more subtle and strategic, there is no necessary need for them to understand any more of security than buyers.” Ian concludes that in cybersecurity, there is no asymmetry as both buyers and sellers have insufficient information available because knowledge is too expensive for either party to obtain. “The efforts of either party could see them knowing more than the other, but even reasonable efforts leave parties without sufficient information to make a rational decision”.

Although many wouldn’t want to accept the thought that neither buyers nor sellers have any idea how to solve the problem of security breaches, this might be the only rational explanation for what we are seeing. Everyone is simply trying to do their best, knowing that there can be no certainty no matter how hard they try.

Cybersecurity is a market for silver bullets

If security is not a market for lemons, then what is it? A market for silver bullets. As Ian explains in his thought-provoking piece, “A silver bullet is a term of art in the world of software engineering for a product or process that is presented as efficacious without any logical or rational means to back up that claim. Silver bullets are goods traded in markets in insufficient information. Along with the diagonal of lemons and limes (asymmetric information), they form the markets in imperfect information”. He goes on to say that “the buyer has no good test with which to confirm the veracity of the seller, and so cannot economically determine ex ante that the good meets needs. The seller lacks that information as well, as he has no advantage with the attacker”.

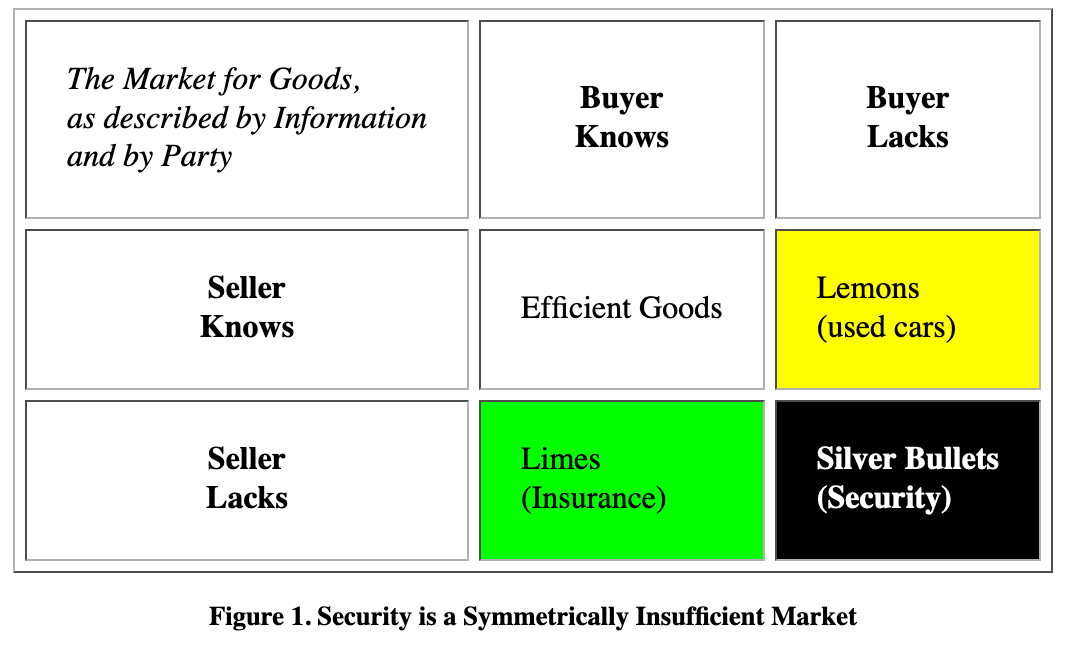

The image below illustrates the distinction between four types of markets as defined by their access to information:

Market for efficient goods. In this market, both buyers and sellers have access to information. Think about buying a new Macbook: a buyer can easily evaluate its capabilities and make an informed decision about the purchase. A seller has as much information about the product as the buyer.

Market for lemons. In this type of market, a seller has disproportionately more information than a buyer. The used car market is a perfect example of this phenomenon.

Market for limes. In this type of market, a buyer possesses disproportionately more information than a seller. A perfect example of such dynamics is insurance. A person buying, say, travel insurance, has a better idea of their plans and potential risks than an insurance provider.

Market for silver bullets. In this market, neither buyers nor sellers have sufficient information about the goods sold. Security is a perfect example of this phenomenon as neither a vendor nor a CISO can guarantee that they know more than the attackers and that the product will prevent every threat it was supposedly built to protect against.

Source: “The Market for Silver Bullets”

Implications of security being a market for silver bullets

Since buyers cannot evaluate security products, they look for other signals

Since security is a market for silver bullets, neither buyers nor sellers can confidently evaluate security solutions. Industry participants are forced to make decisions primarily on the basis of other factors that may or may not strongly correlate with the tool’s ability to achieve security outcomes. Here are some of the signals security buyers and other market participants frequently use to understand whom to trust:

Investors backing the company. Being funded by a top-tier VC firm is seen as a sign that the startup is more “promising”.

Mentions by analyst firms. Having an analyst firm mention the company in their report can provide a big boost and generate fresh demand for the startup.

Background of the founders. There is often an implicit assumption that when founders have a big brand name such as Israeli Defense Forces or a US-based three-letter agency on their resume, they are likely to have a better product.

Customer logos on the company website. Buyers are looking for signs that other reputable organizations trust the startup with their security.

Angel investors and advisors. Security buyers are often interested in understanding if the company has the support of reputable industry leaders.

Peer feedback. Security leaders frequently reach out to their peers in private communities to ask about their experience with specific tools. While this feedback in itself can be biased and anecdotal, it’s better than not having anything at all.

User experience and ease of adoption. This includes the presence of technical documentation, product design, the amount of time it takes to get started with the solution, and so on.

Marketing hype and public presence. It appears to us that factors such as the size of the RSA Conference booth may matter in the security industry, hence why year after year, security vendors keep investing in their public image.

Venture in Security has previously discussed that in cybersecurity, the trust factor and time to trust play a critical importance in the buying journey. For CISOs and security practitioners, indirect signals that the company is credible and worth looking at matter much more than the marketing of the products themselves. If customers are buying a promise, the reputation of people (or a company) who are making that promise plays a more important role than what they are promising.

Industry analyst firms are a perfect example of a party that, due to the lack of information on both sides, holds tremendous power in the industry. Analyst firms perform information arbitrage: they talk to both customers and vendors, collect other signals from the market, and sell their aggregated recommendations to both buyers and sellers. What is particularly interesting is that analysts themselves have a limited view of security: they see trends and categories, but no firm in their right mind would suggest that one vendor has a higher chance of stopping the breach than the other. In the absence of signals related to security, analyst firms came up with their own ways to segment sellers into categories.

Source: Gartner

Source: Forrester

Take these charts above. We would argue that if we plot security vendors over them, neither will give us anything useful to understand which vendor is more likely to make the company more secure. Importantly, they aren’t even trying to: they focus on general, market-focused characteristics instead. It’s akin to comparing two silver bullets by saying that one is heavier, and another is better designed: it’s good to know but absolutely irrelevant if we want to know which of the two is more likely to stop a vampire. We’ve learned to interpret signals from analyst firms and use them in our purchasing decisions, even though the criteria they use to evaluate security tools have little to do with security.

The elephant/“silver bullet” in the room – AI

In an essay on security silver bullets, it would be remiss of us if we didn’t mention AI.

AI is a very topical silver bullet. It is being touted as the secret ingredient that would increase the effectiveness of any security tool, irrespective of the problem domain – whether it is automating SOC, automatically fixing security vulnerabilities in code, or improving cloud security. Startups these days don’t get funded if they don’t mention the use of AI.

However, AI is a perfect example of a silver bullet that highlights the key themes of the original essay from Ian. VCs who are funding these startups don’t really know if the AI is doing anything/adding any value. Founders are either actively trying to leverage AI or are being encouraged to use AI by their investors. Customers have no effective way to verify if an “AI-enabled” cyber vendor is in any way more effective than a “non-AI” solution.

In most scenarios, AI is now just a buzzword, which effectively doesn’t really mean anything. Few research papers actually point to the ineffectiveness of AI in solving security problems (at least as of today). In a recent paper from David Wagner et. al titled “Vulnerability Detection with Code Language Models: How Far Are We?", the authors performed an unbiased analysis of whether the state-of-the-art LLMs (like GPT-4) are effective at detecting vulnerabilities in code. The answer was simple - "Unfortunately, not". The conclusions state the current LLMs are quite far from effectively solving this problem and need significant work. Unfortunately, such unbiased and objective evaluations of various solutions are rare.

A lot of what we know as “best vendors” is the expression of herding

Ian’s research paper arrives at the conclusion that “changes to the selection of security measures happen slowly, and when they do happen, they tend to ripple fast across the community”. In other words, it takes a long time for security teams to adopt new solutions, but once a certain adoption threshold is reached, the rest of the market starts to move towards that solution because it becomes known as a “category leader”. For vendors, this means that success breeds success: in 2024, buyers need an extra justification to not choose CrowdStrike for their endpoints, Wiz for their cloud, 1Password as their password manager, etc. The very act of picking a certain product is equated to doing “what is best” for the business.

The paper goes on to discuss the idea that which security tools survive and which die is to a large degree based on chance. “The inclusion of a silver bullet [ think - security vendor ] is based on the random chance of being used by a participant in beginning rounds, and surviving the possibility of being isolated and withdrawn. Although this earliest process may be motivated by security thinking, that motivation shrinks dramatically once the set is chosen; deviations are costly. Changes are more likely to relate to indirect effects of the costs and benefits of maintaining the community's set than be to be connected to a good's nominal mission of security”.

The actual security measures are following the same path as vendor selection. As enough people do something, anecdotes start to emerge that it is “working”, and that set of behaviors becomes known as the “best practice”. What is particularly confusing is that many of the so-called “best practices” are not based on evidence. For example, while there seems to be enough evidence that regular password changes may actually do more harm than good, many companies are continuing to enforce policies that require people to change passwords every 90 days. Another example is phishing simulations: although there are plenty of organizations that abandoned this practice, the majority of security teams continue doing it despite the evidence that suggests it is not really useful.

Sticking to what is seen as best practices even if they end up causing harm to security posture is one of the outcomes of herding. As Ian explains, “Deviation from best practices is costly, including towards a presumed direction of greater security… As the cost of breaching the equilibrium is proportional to the number of community members, the larger the community, the greater the opportunities for security are foregone, and the more the vulnerability”. And, “if one player chooses a new silver bullet, other players do not have a better strategy than sticking to the set of best practices, and even the player that changes is strictly worse off as they invite extraordinary costs [ reputational damage for not sticking to the “best practices” - our note ] in the event of a breach”.

Another interesting example of cases when best practices win against security is compliance. Compliance standards tend to encourage adherence to best practices, often at the detriment of the security they are supposedly designed to result in. For example, certain compliance standards dictate the use of training against credential phishing even if the company adopts a phishing-resistant MFA/passwordless solution.

Navigating the market for silver bullets: going into the future

Ian’s paper doesn’t just talk about problems but also offers several suggestions of what could be the solution. Similar to the rest of the article, his ideas for where we could go are still relevant a decade and a half later.

First-principles thinking for both buyers and vendors

As the market gets flooded with silver bullets, it becomes more and more important for buyers to leverage first-principles thinking. Ask yourself what core problem you are trying to solve, and what is more likely going to cause a breach - the shiny new AI model, or something more common like phishing? Based on these answers, buyers should come up with a list of priorities for them and then try to find solutions. Some of these solutions might indeed come in the form of new vendors, but many will be in the form of new processes, open source tools, simplifying the IT stack, or the like.

For vendors, even if it might be easier to raise money using the latest AI hype, the same first-principles thinking can bring a lot of value. Founders should be honest with themselves when trying to understand the underlying problem they are solving, if the target market is big enough, and if the problem area they are tackling is seen as a “high priority” by the buyers. It’s encouraging to still see that companies are getting started in fundamental areas like user identity and cloud security, in addition to all the AI security startups that are popping up.

Encouraging information sharing between security teams

Ian argues that “sunlight is the best disinfectant”. For too long, security teams all over have been relying on the so-called “security through obscurity” - the practice of concealing the details of their security efforts to supposedly strengthen security. The reality is that as an industry, we greatly benefit from sharing our learnings with others. The good news is that we are making progress. More and more engineering-centered security teams are open sourcing tools they built for their own use, and a growing number of companies are allowing their teams to discuss their security efforts at conferences and events. The bad news is that we are not moving fast enough. An average CISO is bound by strict non-disclosure agreements and an average security practitioner is not allowed to speak about most of the work they are doing. This means that the only parties that get visibility into what is really happening in the industry are insurance providers, but they are not sophisticated enough to understand it, nor incentivized to make this data public.

On the other hand, security buyers are actively trading feedback about different vendors. In the past decade, there has been an explosion of peer-to-peer communities where security leaders and security practitioners share their experiences with different security tools. This is starting to change the way security solutions are bought. The great news is that security vendors have no way to affect these communication channels. Additionally, more and more CISOs are becoming members of sector-based Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs). These organizations further enable security leaders to share important learnings and threat intelligence with other trusted partners.

Objective third-party measurements/evaluations

There are some academic papers like the “Vulnerability Detection with Code Language Models: How Far Are We?" paper we mentioned earlier, which do an excellent job at evaluating the effectiveness of tools. We should encourage more active research in this space, especially done by people who don’t have a skin in the game such as those coming from academia. They can even “obfuscate” the name of the vendors, but still compare the effectiveness of vendors in a certain problem domain and publish results. There are some great practitioner-led efforts hoping to fill this gap, and we are optimistic more people and organizations will be supporting these initiatives.

Product-led growth/easy proofs of concept (POCs)

In security, trying products is incredibly hard. This makes it impossible for buyers to quickly test new solutions and verify vendor’s claims. It’s not only the buyers who lack information but the sellers themselves: vendors have no way to understand what their competitors are actually offering, so they just make claims that their tool is better without any proof.

The good news is that more and more vendors are starting to allow customers to try their products self-serve. This is excellent both for vendors and customers –

Customers get to quickly try out these tools without fully deploying them. They can get a sense of the capabilities, ease of deployment, and the overall feel of the product. These POCs should allow customers to bring in their own datasets for quick evaluation.

For vendors, such quick POCs are an excellent way to onboard new potential customers who might be more reluctant otherwise. Additionally, vendors can get more quick feedback about their products instead of having to wait for the full deployment cycle.

Pragmatism vs over-reliance on best practices

Among other things, Ian advocates that the industry should prevent the use of best practices instead of embracing them. He argues that “This could be best done by institutions (associations or regulators) that celebrate daring experiments and differentiation rather than conformance and fear. Institutions would serve better by avoiding best practices, facilitating the open sharing of information, and insisting that members of the flock find their own paths”.

This opinion, although somewhat contrarian given the industry’s push to standardize, does have value. Now, let us be clear: for organizations looking for an easy way to get started with security, a list of best practices can offer a quick how-to guide. Beyond that, it’s critical to emphasize that not only compliance is not the same as security, but companies must understand their own risk profile and make decisions based on that, instead of blindly relying on “best practices”.

Higher accountability for security vendors

The US government continues to push for higher transparency and disclosure around security incidents. The new Securities and Exchange Commission's cyber disclosure rules require that companies share information about how they manage their cyber risks, and report when their measures fall short and cause material incidents.

As this space continues to be more regulated, we also expect more stringent requirements in the future about what a vendor could “advertise” and claims they could make without any evidence.

Where do we go from here? From trying to measure security to building resilient systems

The article states: “In principle, we could replace the signals with the underlying metrics. In education, the elusive metric was productivity. In Security, this is an open area of research, so we can say little conclusively except to underscore the importance of research in security metrics. This approach would move each agent's set of goods away from the set of best practices towards focussing on more precise metrics. Their precision would more clearly relate to the individual circumstances of each agent, and thus force more local alignment and greater sector diversification”.

So far, we have largely failed in our attempts to measure security. What if we can shift the way we think about it and treat security as something we buy to achieve resilience? Feelings cannot be tested or verified, they can be just taken at face value. Resilience, on the other hand, is a way to statistically prove how robust something is, what kinds of attacks it can withstand and for how long, and under what kinds of circumstances it can retain its property.

There is a lot of discussion these days around “secure-by-default” systems. Google specifically has written an entire book on the topic of building secure and reliable systems. Major operating systems like Windows and macOS and browsers like ChromeOS are perfect examples of such resilient systems. Think about it – Chrome is essentially running arbitrary Javascript/code on your machine in a safe and secure way. The path to that safety has been riddled with lots of mitigations and an ongoing effort to keep up with the evolving attacks. But, it is possible, and these fundamental platforms we all rely on are proof of that.

Similarly, these days we don’t really talk about “buffer overflows” anymore. It’s because the industry has evolved through a combination of various mitigation solutions like Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR), Data Execution Prevention (DEP), and better fuzzing/bug-finding tools and even memory-safe programming languages which make commodity software more resilient to exploitation.

In our opinion, this is the way. Trying to quantify security is going to be a losing battle. However, we as an industry can continue to be pragmatic and continue to build more resilient systems.