Top 12 deep dives to understand the cybersecurity market

A selection of 12 of the most critical deep dives for anyone looking to truly understand our industry

There are now nearly 250 deep dives into Venture in Security, many of which are essential for understanding the market, whether you are a CISO, a security professional, founder, investor, or anyone else interested in building a well-rounded view of security. You know as well as I do that there are plenty of reports about individual market segments, but the fundamentals are critical regardless which segment you look at. Venture in Security covers the fundamentals. In this issue, I’ve compiled a selection of 12 of the most critical deep dives for anyone looking to truly understand our industry.

This issue is brought to you by… Tines.

Manual evidence collection, scattered tools, and repetitive audits can take a real toll on security and GRC teams. This new GRC playbook, created by Drata and Tines, offers a practical look at how teams are shifting to continuous, automated compliance.

Inside, you’ll find:

Detailed workflows for evidence collection, monitoring, audit prep, and vendor risk

Implementation guidance from credential setup to scaling

Best practices for building resilient, proactive GRC programs

Top 12 deep dives to understand the cybersecurity market

Why there are so many cybersecurity vendors, what it leads to and where do we go from here

It is common to hear that there are “too many vendors” in cybersecurity, and that “we don’t need 200+ products in the same category doing the same thing”. What is rare is seeing analysis as to why there are so many similar vendors - what is driving the establishment of the new companies, and fueling the cybersecurity gold rush.

In this article, I am looking at some of the factors that lead to the emergence of hundreds of “me too” startups, why relatively few businesses in the industry fail and equally, few win big, and why there are only 18 pure-play cybersecurity companies listed on the US stock exchange.

It’s been nearly 3 years since I published this article but it is as relevant today as it was back then.

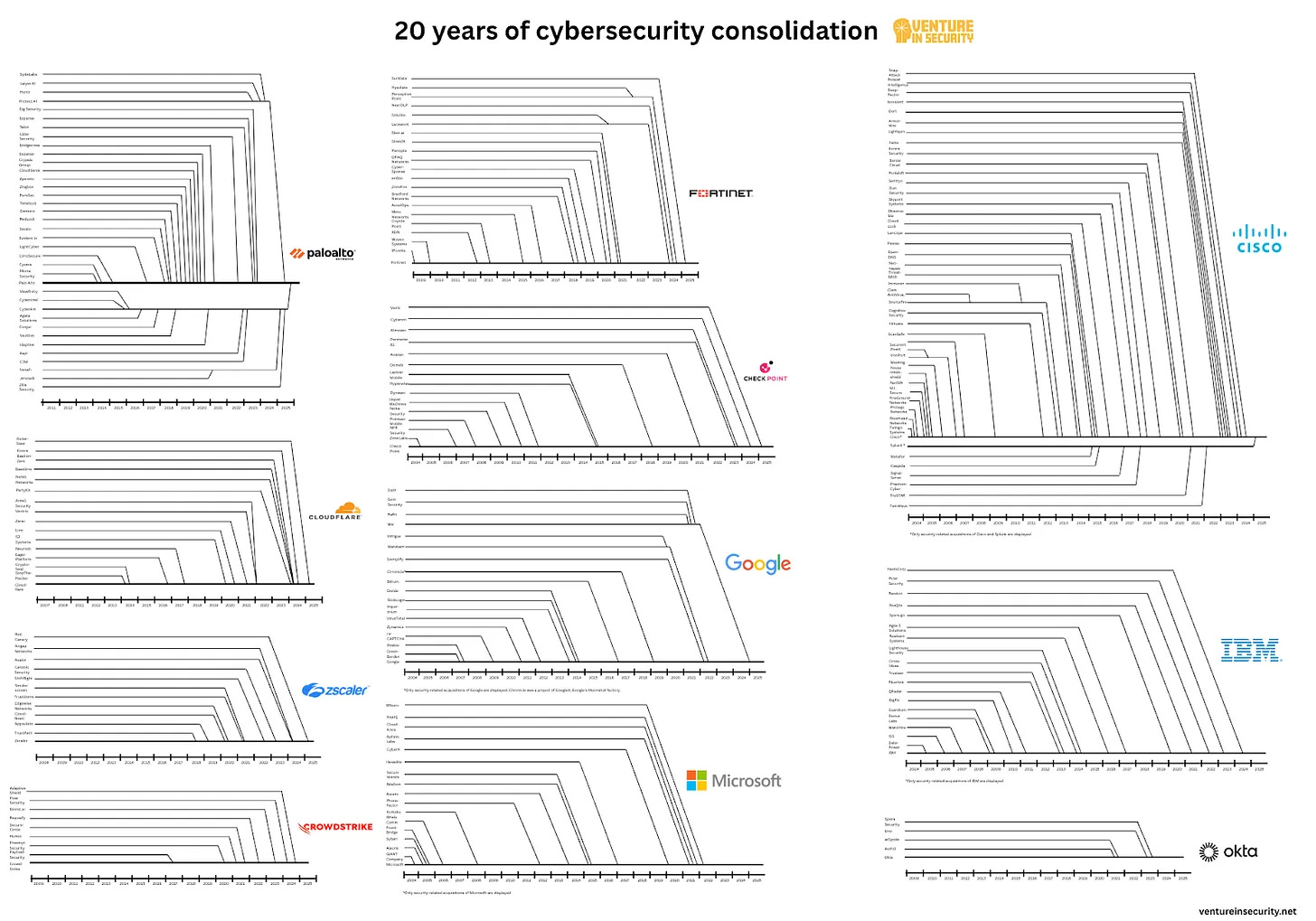

20 years of cybersecurity consolidation: how 200 companies became 11

Everyone in cyber likes to talk about consolidation but very few people understand how it looks in the wild. This isn’t a usual article, it’s a lookback at the past 20 years of consolidation history in our industry. Here’s a preview:

12 ways to fail a cybersecurity startup

“Why do startups fail?” is one of the most commonly asked questions among anyone interested in building a startup. At first glance, a lot has been written about this problem. However, wherever I go, I continue to see three things:

Most of the analysis is based on the consumer startups

Most of the analysis lacks the context of the cybersecurity industry

Cybersecurity founders repeat the same mistakes over and over again

For a variety of reasons, both success and failure in cybersecurity look different compared to other industries. In this piece, I offer a guide to failing a cybersecurity startup, highlighting some of the reasons I have seen startups fail, and offering insights and advice to avoid the failure.

Splunk, Okta, Cylance, Palo Alto, CrowdStrike, and Zscaler mafias in cybersecurity

Some companies play an outsized role in shaping the industry: not just because of what they accomplish, but also because of the kind of startups their alumni create. In this piece, I dive into Splunk, Okta, Cylance, Palo Alto, CrowdStrike, and Zscaler mafias in cybersecurity.

This article is a continuation of the series about the cybersecurity mafia networks. I’ve also written about Check Point mafia, the impact of Foundstone, Juniper Networks & Cisco, as well as @stake, NetScreen, IBM, Israel Defense Forces and the US Armed Forces mafia networks in cybersecurity.

Let’s have an honest conversation about the state of cybersecurity

In this piece, I am offering a very direct and real perspective about what I think are the main drivers for companies to spend on security. Spoiler alert - yes, the majority of the companies buy security products for compliance, but there’s much more to this.

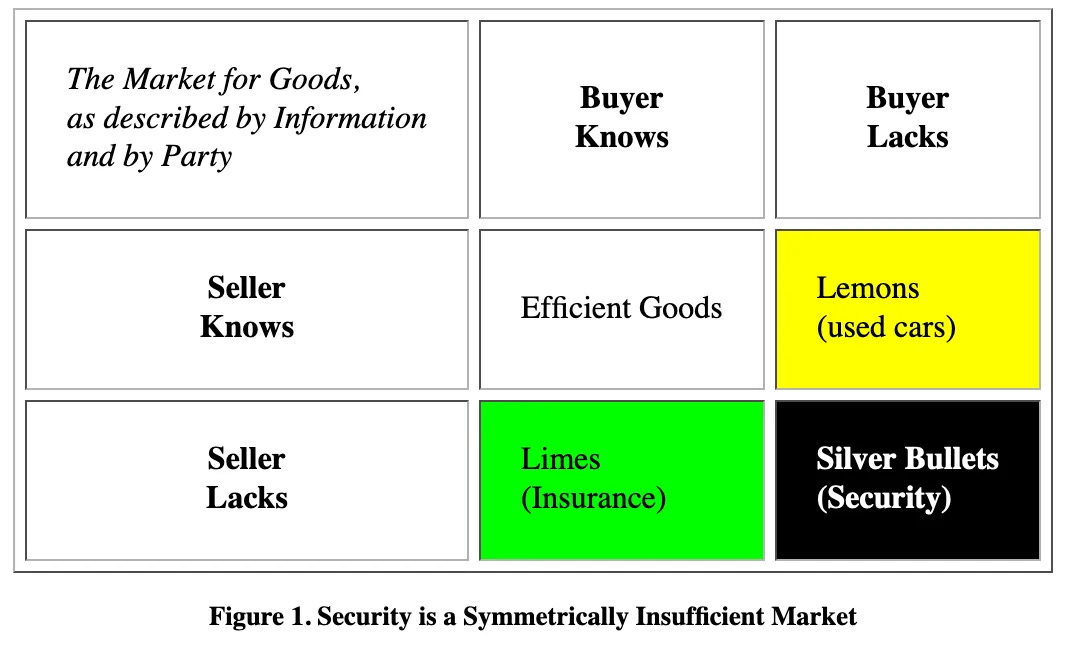

Cybersecurity is not a market for lemons. It is a market for silver bullets

In this piece, co-written with my friend Mayank Dhiman, we are looking into the reasons why security is not at all a market for lemons; instead, it is a market for silver bullets. Neither Mayank nor I didn’t come up with this idea on our own. Our article is centered around the analysis of an excellent essay written by Ian Grigg back in 2008 titled “The Market for Silver Bullets”. Since we connect our own ideas to those expressed in Ian’s article, please assume that anything not listed in quotations is our perspective and not that of Ian.

Ian’s essay is a must-read for anyone trying to understand the dynamics of cybersecurity on a deeper level, and we hope this article will inspire many people in the industry to give “The Market for Silver Bullets” a read.

Source: “The Market for Silver Bullets”

The only six cybersecurity markets large VC funds actually care about and why security startups don’t have a moat

At first glance, there are hundreds of important problems that need to be solved in cybersecurity. This, in turn, presents opportunities for thousands of security startups, making the whole security technology landscape look like a bingo card.

The reality, however, is very different. Most security problems are niche, and hence why they simply have no potential to lead to outsized, venture-scale returns. The problems that aren’t niche, tend to follow specific patterns. In this piece, I am taking a closer look at what these patterns are, and what areas of security actually constitute large markets. The short of it is simple: while things change, tech changes, and attackers also change, decades later, the top markets remain the same:

Network remains foundational despite the fact that many proclaimed that “network is dead”. As companies started to move away from traditional networks, the problems of connectivity and security came up once again. The solution which became known as Secure Access Service Edge (SASE) combined networking and security into one product.

Endpoint security remains critical for security and ransomware prevention since people still do their work on the workstations the way they did it a decade ago. For better or for worse, ChromeOS is not yet a OS standard heavily used in enterprises, and it’s unlikely to become one anytime soon.

Identity has truly become the new perimeter, and since access is now based on user and machine identity, the market has exploded.

Email security remains big because, despite the introduction of Slack, Teams, and other collaboration tools, that is still how businesses communicate with the outside world.

Security information and events management (SIEM) remains the foundational technology that allows security teams to aggregate, correlate, and analyze data, or in other words, to do their jobs.

One new kid on the block that VCs care about is cloud security:

As companies started to move to the cloud, cloud security emerged as a new player. Two decades later, we now have players such as Wiz that are centralizing that space.

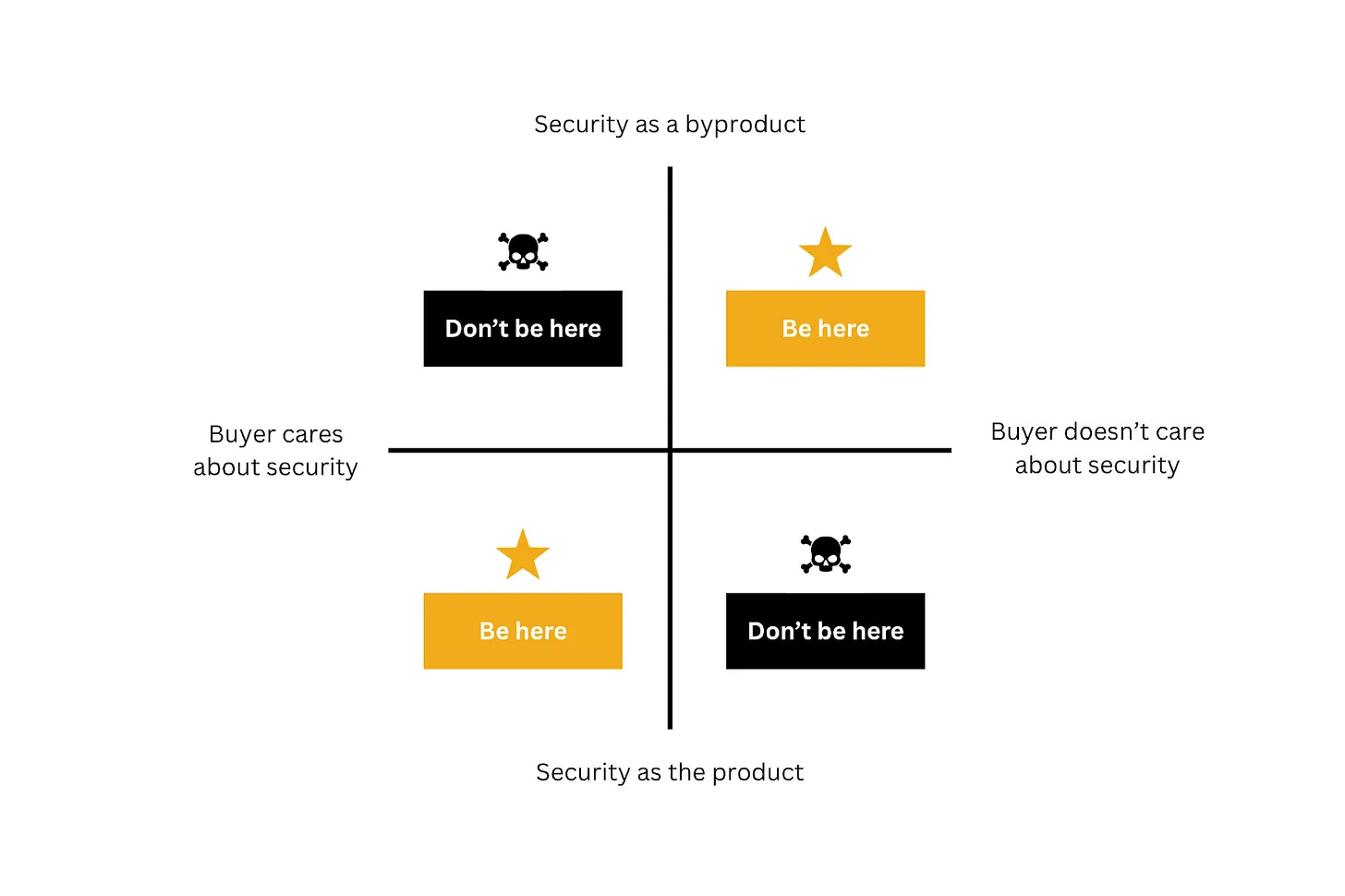

To solve security problems, you don’t have to build a security company

If you were to ask security founders what they think are the best ways to make companies more secure, they would probably tell you different ideas about getting CISOs to buy new security tools. That’s not wrong per se - CISOs control security budgets, set strategy, and are responsible for the organization’s security posture. This thinking, however, is very limited for a simple reason: some of the biggest improvements in security have come from products that were never sold as “security” at all.

In this issue, I discuss the concepts of security as the product vs. security as a byproduct, and what they mean for founders.

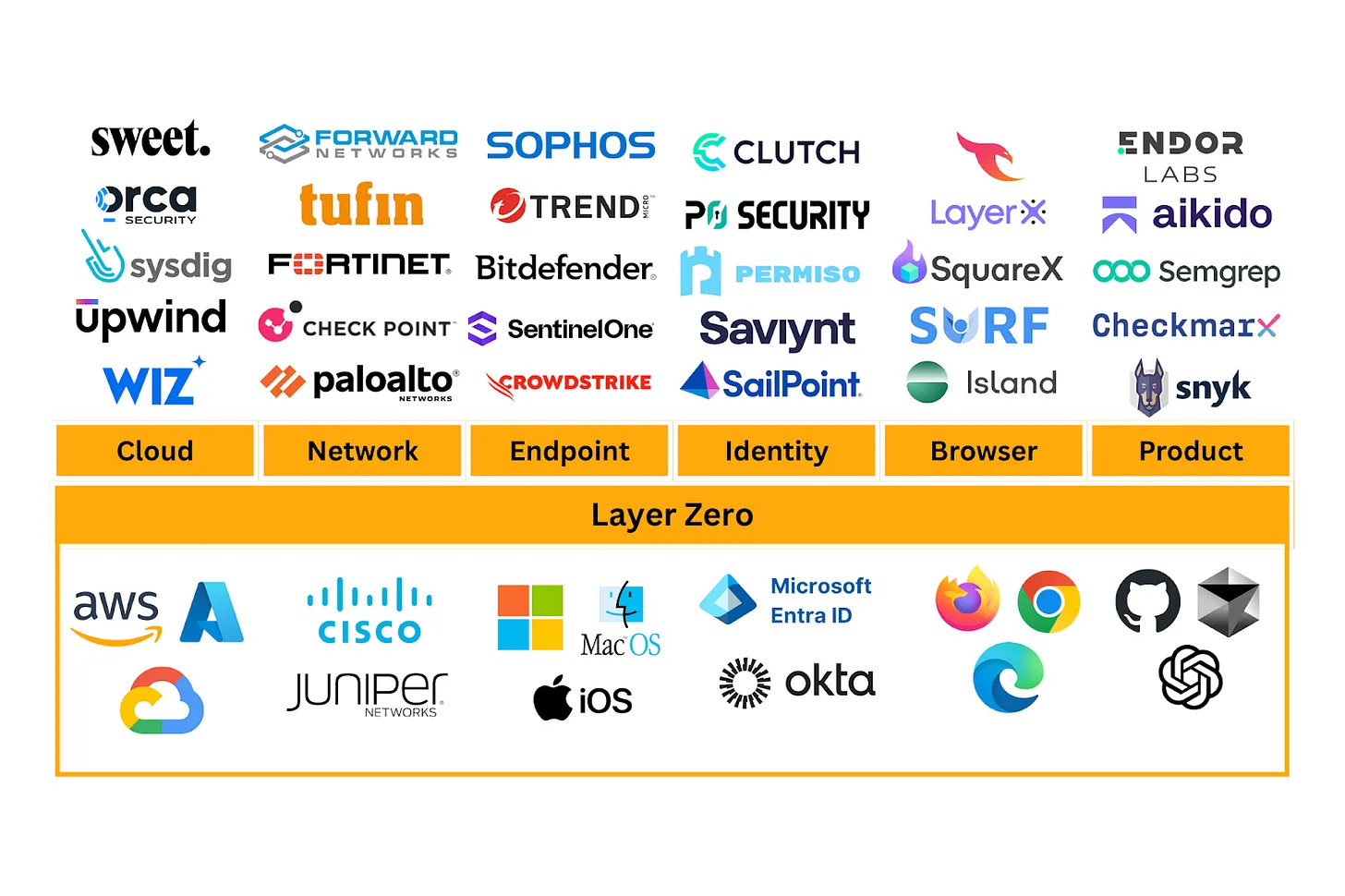

Competing with layer zero in cybersecurity

Exploring the idea of a “layer zero” - why it matters, what makes it powerful, and how security startups can strategically position themselves around it.

The entities best positioned to deliver real security are the ones building the core technologies. A cloud provider is logically in the best place to solve cloud security; an operating system vendor is closest to solve endpoint security; an email provider sees everything that flows through their infrastructure so they should be in the best position to solve email security; an identity provider already governs user access so they should be able to take care of identity threat detection and response effectively. These foundational providers own the systems that define how security boundaries are created, how access is enforced, and how data flows, so they have the ability to bake security in. It is these providers that I define as layer zero.

Layer zero refers to the foundational layer of infrastructure and technology that other tools depend on. It’s where control points often emerge - identity platforms, cloud service providers, and operating systems. These are not just passive infra providers; they actively shape the rules of engagement for all other tools. For those that own layer zero, adding security is often just an architectural decision (a toggle, an API extension, a bundle, etc.), while for everyone else, namely the vendors operating on top of these platforms, delivering security becomes a negotiation with the underlying layer. That’s the power of owning the foundation, and the challenge for everyone who doesn’t.

Owning the control point in cybersecurity

In every business function, there are control points - systems that teams rely on the most and that concentrate the most power and influence over operations. In cybersecurity, identifying these control points is critical for understanding where decisions are made, where workflows converge, and where to prioritize investment. Dave Yuan offers a useful heuristic: “If you had to turn off all the systems in your stack, which ones would you turn off last?” The answer to this question is a good heuristic to figure out which platforms are core to the function and which are secondary.

For most cybersecurity teams, the primary control point is their SOC platform, usually a SIEM or XDR. It’s where telemetry is aggregated, alerts are prioritized, and investigations happen. It’s the default interface for day-to-day security work, and often the first system looked at during a breach or audit. While the tools used may vary, nearly every mature team has something in place that acts as the operational center of gravity for detection and response.

Other domains within security have their own control points. Whoever owns the control point, gets an opportunity to build a billion-dollar company.

Explaining the complex world of channel partners in cybersecurity and looking at their past, present, and future

Channel partners are critical for cybersecurity because no company can reach millions of businesses around the world on its own. Establishing and maintaining relationships spanning countries, languages, time zones, and industries is not feasible without reliance on partner networks.

Over the past decade, the world of channel partners has been evolving. In this piece, I am diving deep into this evolution, what it means for the industry, and the future of security.

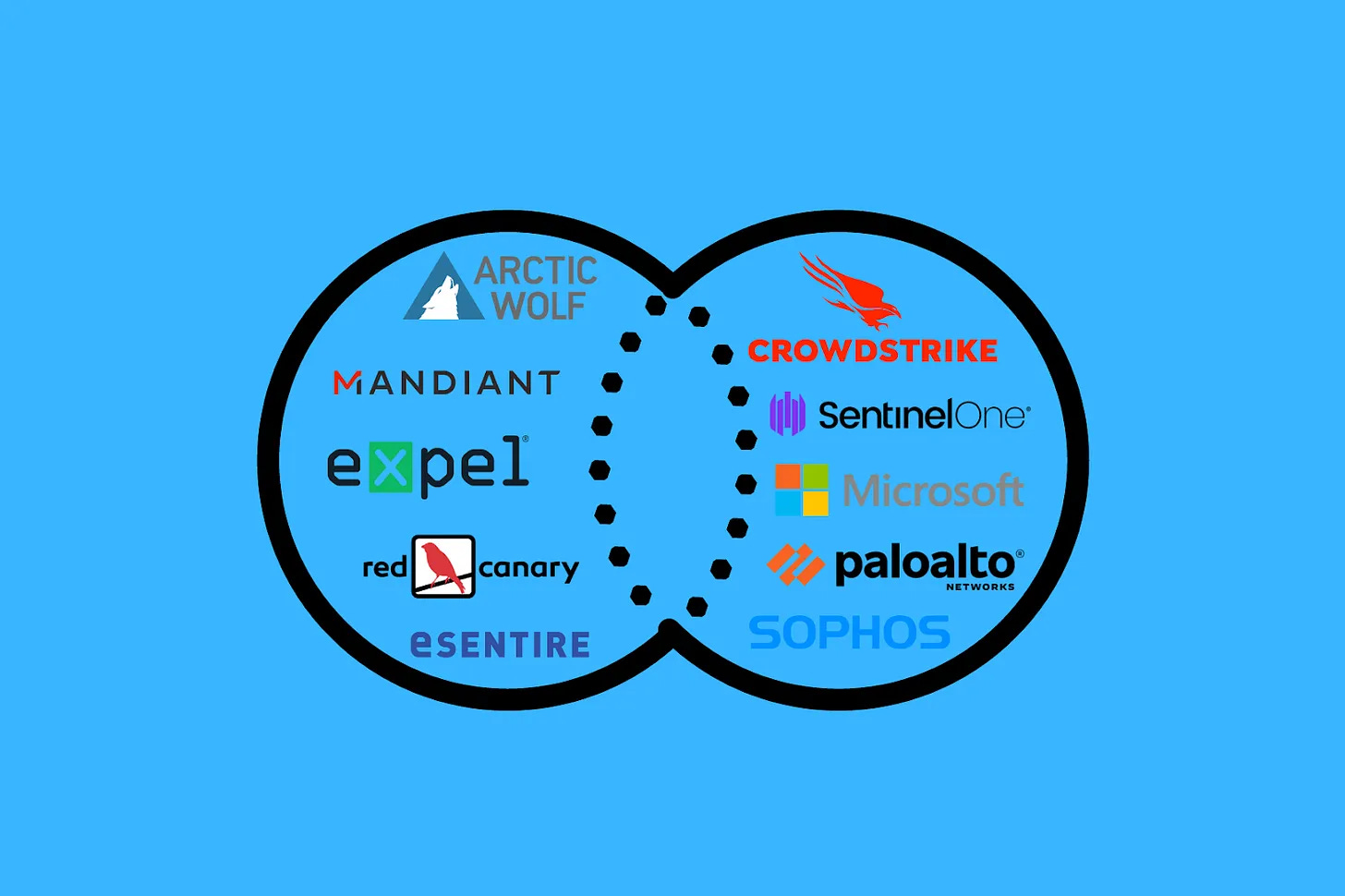

Enmeshment in cybersecurity: blurring boundaries between products and services

A decade ago, anyone looking to segment and classify cybersecurity companies would first split them into two buckets: products and services. Today, that difference has been disappearing as more and more service providers have been building products, while product companies are now offering services. In the deade to come, I think the line between the two is going to fully disappear.