Owning the control point in cybersecurity

Exploring the idea of a “control point” - why it matters, what makes it powerful, and how security startups can strategically position themselves around it.

Definition of a control point

Dave Yuan, a venture capitalist at Tidemark who has spent over 20 years investing, likes to discuss the concept of a “control point.” Although I most definitely recommend reading one of his articles or listening to his podcasts, here’s the tl;dr of what it means.

This issue is brought to you by… Tines.

I know what you might be thinking - everyone is publishing a guide to AI these days. If you’ve read one, you’ve read them all…right?

Here are three reasons why this Securing AI in the enterprise guide from Tines is different:

Hear from CIOs and CISOs pioneering the secure deployment of AI tools

Learn step-by-step approaches for AI implementation, while maintaining privacy, compliance, and control

Get equipped with the right questions and criteria to evaluate AI vendors and ensure their solutions meet your security standards

Different types of companies, particularly SMBs, generally have one or two systems that can be defined as “control points” - they’re very important, they touch multiple assets and workflows, it’s where people spend most of their time, it’s mission-critical systems that if a startup lands there, it earns the right to expand into other areas and build a broad platform offering. Small and mid-sized businesses, as Dave explained, typically have one or two control points. Usually, these are the systems they spend most of the time in as they go about running their business. A fractional CFO, for example, would most likely spend most of their time between something like QuickBooks (since that’s how many customers would share their accounting records) and a CRM (since that’s where they would track their marketing and sales activity). I am sure you get the idea.

While for SMBs, a control point is a central place for managing their business, at large enterprises, control points tend to be very function-specific. They are very easy to spot: sales teams spend most of their time in Salesforce, human resource teams in Workday, engineering teams in Atlassian or GitHub, design teams in Adobe, finance teams in NetSuite, and so on. Each of these systems is a control point for their respective function.

With the basics out of the way, let’s dive into the main topic - owning the control point in cybersecurity.

Defining a control point in cybersecurity

In every business function, there are control points - systems that teams rely on the most and that concentrate the most power and influence over operations. In cybersecurity, identifying these control points is critical for understanding where decisions are made, where workflows converge, and where to prioritize investment. Dave Yuan offers a useful heuristic: “If you had to turn off all the systems in your stack, which ones would you turn off last?” The answer to this question is a good heuristic to figure out which platforms are core to the function and which are secondary.

For most cybersecurity teams, the primary control point is their SOC platform, usually a SIEM or XDR. It’s where telemetry is aggregated, alerts are prioritized, and investigations happen. It’s the default interface for day-to-day security work, and often the first system looked at during a breach or audit. While the tools used may vary, nearly every mature team has something in place that acts as the operational center of gravity for detection and response.

Other domains within security have their own control points:

In network security, it's typically the system where segmentation and firewall policies are created and managed.

For compliance, it's the platform used to configure controls, collect evidence, and prepare for audits. These systems define how security is applied and measured within their respective domains.

In identity, the control point is the place where access policies are managed, spanning users, roles, and service accounts.

In application security, it’s the platform where alerts from various scanners are triaged and remediation is tracked.

In each case, these control points are where teams spend time, drive outcomes, and establish leverage, making them key areas for new product development, vendor consolidation, or platform bets.

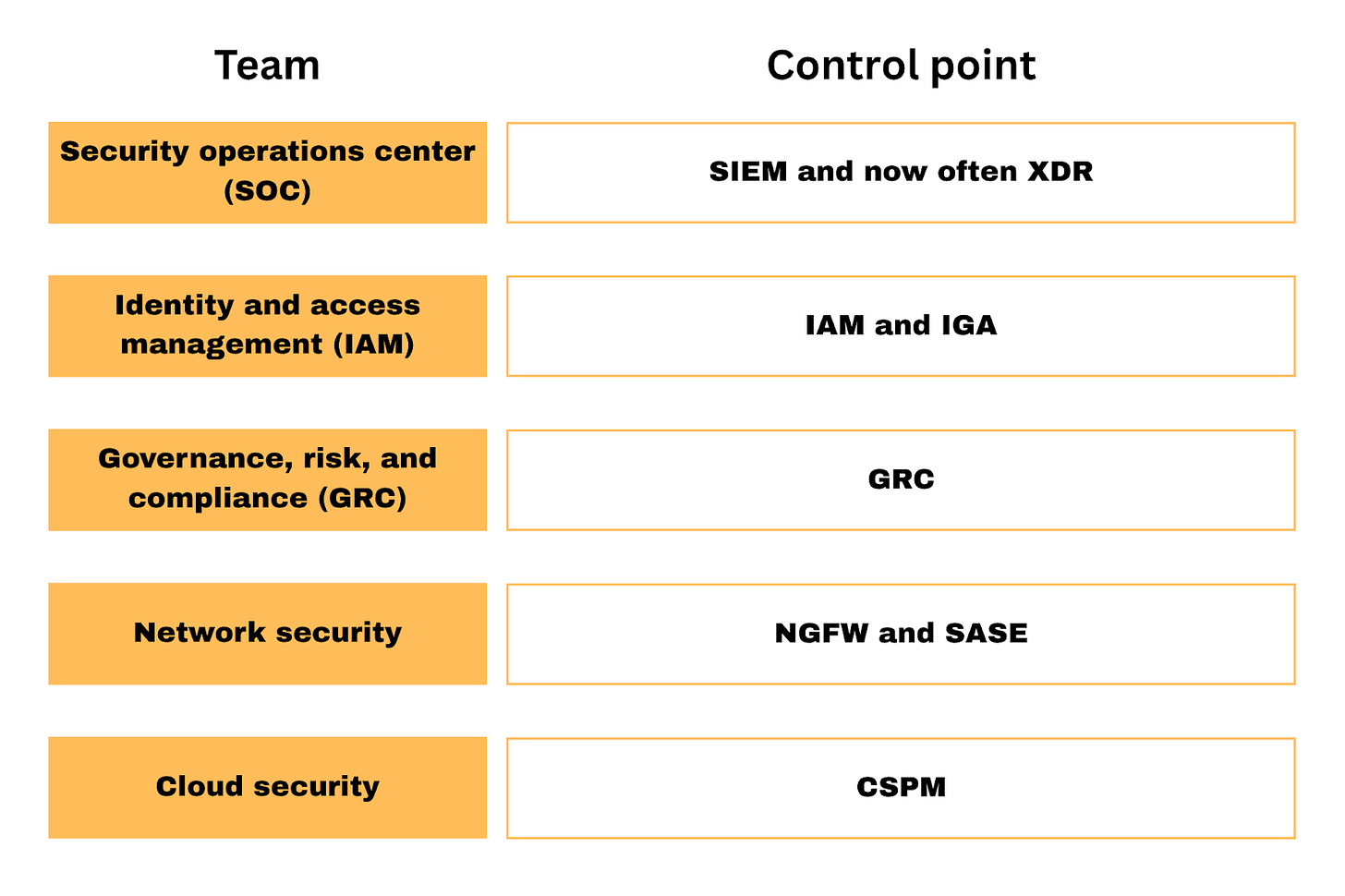

Generally speaking, each control point is mapped to a team, and the bigger the team, the more data it handles, the more important that control point is. It’s not a coincidence that these five groups correspond to the largest security markets:

An easy (although also painful) way to identify a control point is to pitch a solution to a security team and hear them say “This sounds like the feature in the main tool X we are using to manage our work on the team”. To a cloud security team, everything will often sound like a CSPM; to a SOC everything feels like it should be a feature of a SIEM, etc.

This gets much more interesting when we dive into the concept of control point deeper.

Typer of control points in cybersecurity

Broadly speaking, there are two types of control points in cybersecurity: access-centric and workflow-centric.

Access-centric control points

While security conversations tend to concentrate on detection, many of the most foundational control points in an organization are access-centric. Two core areas that fall under this bucket are network and identity - domains that define who can access what, where, and how.

There are several key aspects of access-centric control points. First, access is about… well, access. The fundamental question is who needs to access what. Security exists to protect that access, but the end goal isn’t prevention or detection; it’s enabling the right access under the right conditions. Second, access systems are deeply embedded into how companies operate, shaping organizational workflows, defining how teams collaborate, and governing how systems interact. If there’s one area where security is clearly a form of enablement that would be when we’re talking about identity and network. These aren’t bolt-on tools, they sit at the intersection of IT, security, and business operations.

The fact that identity and network control points govern who can access what means that they sit in-line with traffic/access, which makes them both high-risk and high-impact. Access-centric control points are tightly integrated with business workflows, and changes in these systems can significantly impact how employees, vendors, and systems interact. Because of this, access-centric systems are highly embedded and difficult to replace, creating a level of stickiness that detection-centric platforms often don’t match:

It’s not hard to replace an identity threat detection and response tool, but it’s very hard to replace an identity provider (IDP)

It’s similarly not too hard to replace one network detection and response tool for another, but replacing firewalls or moving from one SASE vendor to another is a different game.

The stickiness for access-centric control points comes from their embeddedness in business operations, and that’s also what creates opportunity: startups who can get their solutions deployed in-line, have a lot of opportunities to expand. What makes this opportunity even more lucrative is the exclusivity of access: most companies wouldn’t deploy more than one proxy, or roll out more than one IDP (barring special cases with M&A, etc.).

Workflow-centric control points

Workflow-centric control points represent the other major class of control points. These are systems where security teams spend the majority of their time managing their respective function and operationalizing alerts, findings, and tasks they need to manage. The most prominent example is the Security Operations Center (SOC) platform, typically powered by security information and event management (SIEM), what’s increasingly more common - extended detection and response (XDR), or sometimes - security orchestration, automation, and response (SOAR) solutions.

Outside of cybersecurity, core data systems (POS systems in retail, property management systems in hospitality, etc.) typically become control points because they manage critical business data and therefore become the place where all the transactions have to pass through. In security, SOC is the prime example of a control point because it manages the most critical function of our industry, detecting and responding to incidents. What makes workflow-centric systems powerful is the sheer volume and importance of the data they manage (alerts, indicators, system anomalies, behavioral patterns, and signals from across the attack surface). The more data a system holds, the more valuable and sticky it becomes, something I discussed several years ago in a piece on the “data gravity effect”.

Cloud security has added new complexity here. In theory, platforms like cloud security posture management (CSPM) are no different than other posture products (identity, SaaS, etc.) in that all they do is highlight misconfigurations and help security teams drive resolution. The fact that CSPMs have become a control point in their own right illustrates a critical point: for any detection-centric tool to rise to the level of a control point, it has to 1) anchor itself to a critical attack vector, and b) become the tool of choice for a specific security team. In the case of CSPMs, the attack vector is cloud misconfiguration, a top cause of breaches in modern environments. It’s not the breadth of features that gives these tools weight, but their focus on real, high-impact risks. What I think is going to be interesting is whether cloud security alerts from the relatively new cloud detection and response (CDR) tools will go to SOC. If they do, this will diminish the role of CSPMs/CDRs and further elevate the role of SOC as a cybersecurity control point.

GRC platforms also fall into this category, since they are where compliance teams do most of their work, aggregating evidence, defining controls, and shaping behavior through the lens of audit readiness. Like the SOC, they’re driven by data, but their role is to defend against auditors rather than attackers.

While there are many types of detection and response tools and posture teams in security, only the ones focused on a critical area of focus and capable of becoming a home for a security function can evolve into a security control point. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, network security reigned, and network-focused solutions owned the security control point. Then, around the 2010s, the focus shifted from networks to the endpoint, and endpoint security companies earned the right to consolidate SOC. Who knows what it will look like a decade from now. Throughout all this time (or rather since Splunk convinced us that centralizing security data is a good idea), SIEM platforms have been the main control point SOC teams rely on.

Owning the control point in cybersecurity: a founder perspective

Control points and platform creation

In cybersecurity, control points naturally consolidate into platforms because they represent the most critical points of value exchange: these are the systems where decisions are made, actions are taken, and day-to-day workflows are anchored. As a result, owning a control point isn’t just about solving one narrow problem, it’s about establishing the foundation upon which adjacent capabilities can be layered. That’s why control points tend to evolve into platforms, and why platform ownership becomes strategically valuable. Whoever owns the SOC interface, for example, has a direct path to expand into broader detection and response: threat intelligence, automation, forensics, and even compliance reporting. Similarly, if a company owns identity policy management, it can expand into access requests, just-in-time provisioning, and governance. The same applies to network policy management: controlling it creates leverage to move into segmentation, traffic inspection, and even identity-aware networking. The control point is the wedge; the platform is the outcome.

This is why dominant platforms are so hard to displace. There’s usually only one identity engine, one network proxy/policy management layer, and one interface security analysts rely on daily. Once embedded, these systems become the place where security teams live, and where they naturally want more capabilities to reduce tool sprawl. The result is a strong gravitational pull: own the control point, and you earn the right to expand; compete at the edges, and you’re constantly fighting for attention and survival.

Challenging companies that own the control point

After a control point is established, it is extremely difficult to displace head-on. Whether it’s the IDP for managing access policies or the SOC interface for detection and response, these systems are embedded into workflows, tied into multiple teams, and seen as "too critical to fail." Smart startups don’t assume that they can, say, displace Okta by building a better Okta.

Challenging companies that own the control point is only possible from the side. In other words, startups cannot go head-to-head, they have to surround the control point with different value-added products and services. If they are successful, then over time they can subsume most of the functions the control point offers, turning it into a system of record nobody ever needs to touch.

In access-centric security domains, that might mean surrounding the identity provider with adjacent capabilities like just-in-time access, automated provisioning, SaaS entitlement management, or shadow IT discovery. These products don’t compete with the core identity engine directly; instead, they make it easier to work with, extend its capabilities, and gradually become the place where decisions are made. In real life, I think the only certain way to subsume an access-focused system of record is to build a policy engine in front of it. For example, to unsit Okta, it could be possible to build a policy engine in front of Okta that over time would turn Okta into a “dumb” policy enforcement point. This isn’t a theory; there appear to be a number of startups trying to execute this playbook right now, building a layer on top of Okta.

The same pattern plays out in detection-centric environments. You don’t replace the SIEM directly; you surround it with value. A new platform might start by offering faster search, enriched context, alert prioritization, or collaborative investigation workflows. As more analysts start their day in this new interface, the legacy detection engine would hopefully fade into the background, remaining the place where data lands first, but not where decisions happen. Eventually, even that role can be replaced by shifting ingestion pipelines and making the “system of record” fully obsolete.

In theory, the long game for taking control of entrenched control points is clear: surround, absorb, replace. However, as they say (I love this phrase) - “In theory, there’s no difference between theory and practice, but in practice, there is”. There are a million things that have to come together for a startup to succeed and more factors at play than anyone can predict. The important point is that going head-to-head against incumbents is most likely going to be a tough path to pursue. Instead, it makes sense to surround them with value they are not able to effectively deliver on their own, and over time earn the right to displace their various components.

There are plenty of other ways to build a security startup

There are plenty of other ways to build a security startup without having to build a control point. One of them is becoming the primary telemetry source for an emerging infrastructure layer. When new types of systems gain traction (browsers, AI agents, developer platforms, or edge environments), they often lack mature security visibility. This creates an opening: the first company to offer meaningful telemetry collection in that domain can earn the right to become the tool of choice for monitoring, detection, and maybe even policy enforcement.

Taking this path means establishing new sensors where none yet exist. In AI, for example, new tools are starting to monitor agent behavior, prompt injection, API calls, and access to sensitive data, positioning themselves as the observability layer for a class of systems that may eventually become core infrastructure. The logic is simple: start with visibility, then as adoption and underlying infrastructure matures, expand into control.

This strategy is about betting on the future because it only works if the underlying platform becomes central to how businesses operate. If it does, owning the telemetry layer creates immense leverage, but if it doesn’t, then the company can still do well but it won’t become a control point. Some of the examples are mobile and IoT: both were expected to become dominant platforms, but neither has led to a security control point with the gravity of endpoint, identity, or even cloud. At the same time, startups that built sensors to collect telemetry from these systems and do detection and response over it have generally done fine (as long as they haven’t raised too much capital in the hope of becoming a control point).

If you’re interested in learning more about control points, check out Control Point Patterns by Dave Yuan.

Your point about GRC is sad but true: "GRC platforms also fall into this category, ... but their role is to defend against auditors rather than attackers."

The reality is that GRC is Compliance. The risk management function is performed just to meet the compliance check box.

However, risk management can be reimagined to support defending against attackers. Then we'll move from grC to gRc. I call it Risk-Informed Defense.

Great write-up all around!