Making sense of the cybersecurity industry in seven charts

Breaking down security as an industry, looking at several dimensions: risks, people, money, influencers, talent, and relationships

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Any time I need to make sense of a complex structure, I rely on visuals as they make it easier to break down the complexity into manageable parts, understand how these parts are interrelated, and think about how any one of them can impact the others.

In this piece, with the help of simple visuals, I am breaking down security as an industry, looking at several dimensions: risks, people, money, influencers, talent, and relationships.

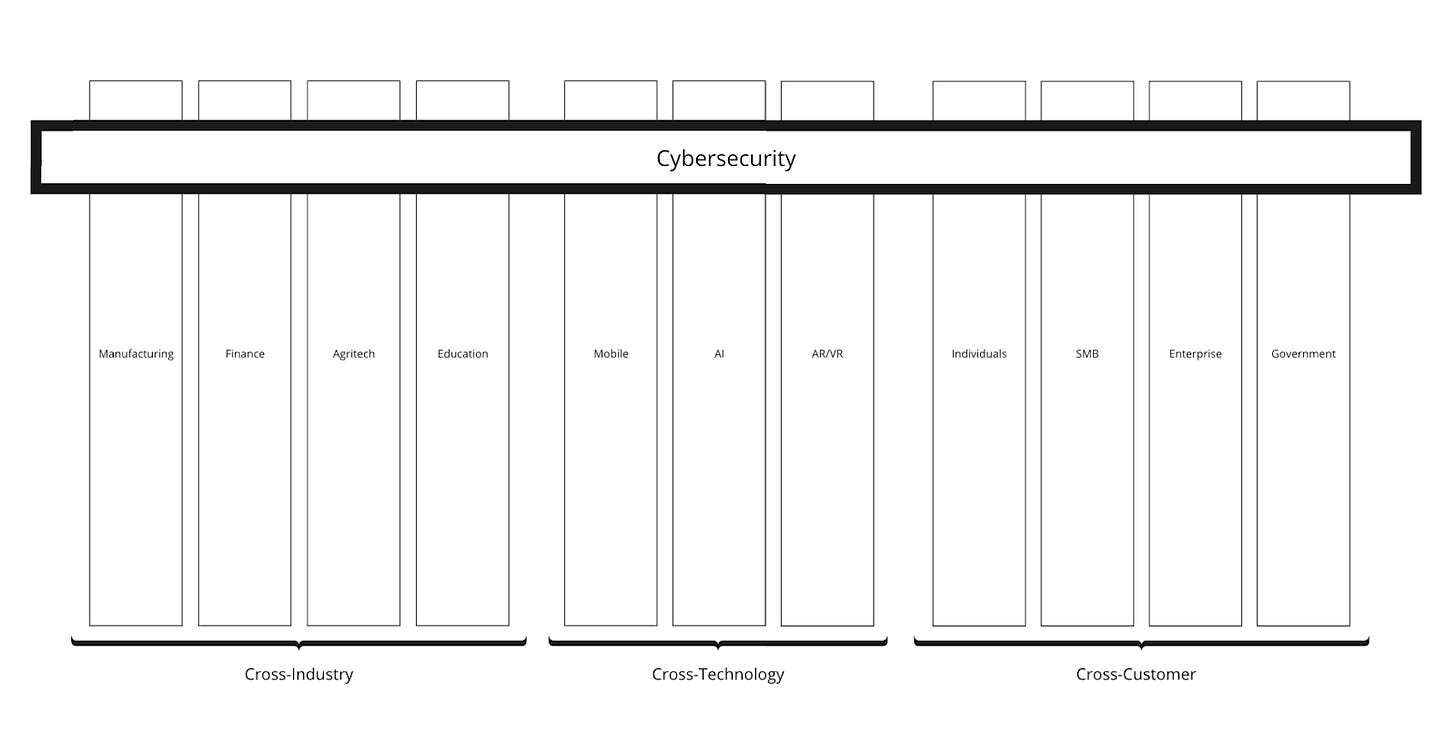

Follow the risks: cybersecurity is a horizontal, not a vertical

When people think about cybersecurity as an industry, they often compare it to other fields such as fintech, agritech, martech, and so on. Although the desire to categorize, label everything, and assign a clearly defined bucket is understandable, in the case of security it doesn’t serve us well. This is because cybersecurity is a horizontal, not a vertical: defending the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data is a cross-industry, cross-technological, and cross-customer need. Whether we are talking about space exploration or mining, education or healthcare, whether we are looking at AI and ML, 3D printing or virtual reality, and whether we work at multinational corporations, charities, or public-private partnerships, every one of them has something that needs to be secured.

Follow the people: CISOs and security practitioners and their role from the ecosystem perspective

CISOs

There are many different ways for CISOs to participate in the ecosystem. Most commonly, I see the following:

A large number of CISOs act as advisors to venture capital firms, offering their perspective during the due diligence, and potentially testing the tools in their environment. For many CISOs, working with VCs is first and foremost a way to stay on top of the industry innovation, and get the ability to hear about new ideas and try new approaches early.

A good number of CISOs are members of CISO networks run by VC firms. I mention them separately from other involvement with VC because they tend to be much more hands-on. For instance, the CISO network run by Team8 involves security leaders in ideation, frequent feedback sessions, and other ways to help their companies.

It’s common to see CISOs act as angel investors either on their own or as a part of angel syndicates such as SVCI and Cyber Club London. Angel network structure isn’t as widespread, and therefore CISOs rarely participate in these.

CISOs often act as advisors to cybersecurity startups, and in some cases even start companies themselves. This is not surprising: since so much of the enterprise sales process is relationship-based, security leaders with strong networks may have a leg up when they choose to go on their own. Many, however, are not as prepared to build and scale product companies given that these concerns are vastly different from the challenges CISOs tackle in their organizations as practitioners.

A small number of CISOs have joined VC firms full-time as investors. Stephen Ward, former CISO of Home Depot and now a VC at Insight Partners is a good example of this.

To learn more about different ways CISOs can help shape cybersecurity innovation, read: How security leaders can accelerate innovation in cybersecurity.

Security Practitioners

Although security practitioners play a lot of the same roles in the ecosystem as security leaders, there are some differences:

Unlike CISOs, security practitioners tend to be much less involved with the investor ecosystem. Very few work with VC funds (and those that do often have an ambition to eventually start their own companies), even less participate in angel networks, and with some exceptions, they aren’t sought out to be a part of CISO networks.

Earlier this year, we launched a Venture in Security angel syndicate to get more security practitioners interested in the startup and venture side of the industry. That said, the percentage of security practitioners exploring these areas remains, in my view, relatively modest.

Based on my observation, security practitioners are more likely to start cybersecurity startups compared to CISOs. The discriminator here isn’t the role but the background and skills: CISOs who are deeply technical are equally (and often - even more) likely to start companies. I think this will continue to be the case simply because security engineers who can write code are much more likely to experiment with new ideas than someone who needs to find or hire a team before they can validate the earliest hypothesis.

Founders

Founders of cybersecurity startups tend to play several roles at once. On one hand, they are recipients of capital and support from all other participants - angels, VCs, advisors, and security leaders. On the other hand, they are also the providers of the expertise and money:

Cybersecurity startup founders often help their VCs evaluate prospective investments.

Serial founders who previously had an exit, or those at the later stages often write angel checks while they build their own companies.

After exiting their companies, cybersecurity startup founders sometimes join VC firms full-time. For example, Zane Lackey, a co-founder and chief security officer of Signal Sciences, is now a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz.

Follow the money: investment options for security startups

Cybersecurity startup founders have a myriad of funding options. The following is an oversimplified overview of the top sources of capital.

Individual Angels

Angels are individuals who invest their own capital. Most commonly, they are founders who have exited their businesses, owners of security service providers, and CISOs with many years of experience (and often a few IPOs or successful acquisitions under their belt).

Because angels invest their own capital, they are not required to achieve specific return multiples (they most certainly want to see returns, but they don’t have obligations to anyone to achieve them). Many angels are active in the industry as speakers, practitioners, advisors, etc., and therefore are looking for ways to actively help their portfolio companies. Individual angels invest anywhere between $5,000 and $250,000 although the actual numbers can vary dramatically.

Recommended reading: Angel investing in cybersecurity: the basics, investment math, and ways to get started

Angel Syndicates

As previously explained, angel syndicates are groups of people who come together to pull money and invest in companies they believe in. Basically, angel syndicates are communities of angel investors making their investments together. Every syndicate conducts business in a slightly different way: some are invite-only while others are open to any accredited investor; some have unique restrictions about who can become a member (such as those that are CISO-only) while others are more flexible.

Members of an angel syndicate receive information about startups looking for funding but are not required to invest in any specific deal proposed by the lead; every person makes their own decisions and chooses if they want to participate (there are no commitments). When people do decide to participate in a deal, there is typically a minimum investment amount they can put in per deal which can be as high as $50,000 or as low as $1,000.

Recommended reading: Fundamentals of angel investing via syndicates for cybersecurity founders and security professionals

Angel Networks

Unlike angel syndicates which are much more open and accessible to accredited individuals willing to invest as little as $1000 per deal, angel networks are generally exclusive clubs of high-net-worth individuals. They are often geographically focused.

Angel networks provide deal flow to their members and expect them to make a minimum of ~$10,000 investment in a startup although the actual terms, roles & responsibilities, and investment minimums vary from one network to another.

Recommended reading: Angel investing in cybersecurity: the basics, investment math, and ways to get started

Incubators & Accelerators

Startup incubators and accelerators are important players in the cybersecurity ecosystem as they provide support and starting capital to startups at the earliest stages of their growth. The way an individual incubator or accelerator is funded will often define its focus and what it can do. Overall, the value add they provide varies, and most cyber-focused accelerators have either struggled to remain relevant and offer the same value they did when they started, pivoted their models (CyLon in the UK), or shut down (CyRise in Australia).

Recommended reading: The tough business of incubating cyber innovation: a deep look at the cybersecurity-focused incubator and accelerator models

Venture Capital (VC)

When most people think about investors, what immediately comes to mind is venture capital. On one hand, it makes sense as most (if not all) of the largest security companies are indeed backed by VC firms. On the other hand, if we were to look at business in general, some might find it surprising to learn that less than 1-2% of all businesses have raised venture capital (although the linked article is quite old, most of the recent numbers I’ve seen tend to be aligned with what it stipulates).

VCs do not invest their own money although partners of VC funds are expected to put in a bit of their capital so that they are financially aligned & motivated to do well. VCs are intermediaries and professional capital allocators: they raise money from institutional investors (pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowments, etc.) and high-net-worth individuals and invest it into companies that have the potential to result in outsized returns.

Recommended reading:

Corporate Venture Capital (CVC)

Corporate VCs or CVCs are another important player in the ecosystem. Companies are motivated to invest in startups for different reasons: fostering strategic partnerships, building ecosystems around their own offerings, or simply generating financial returns. Whatever the reason, what matters is that more and more corporations are starting to offer capital to cybersecurity startups. Most CVCs do not lead rounds; instead, they follow (co-invest small amounts alongside a lead VC).

CVCs provide value in different ways, including:

By becoming a customer and adopting the technology founders build

By leveraging the established distribution channels and selling the product

By providing access to the talent the startup would not be able to access otherwise

Recommended reading: Corporate venture capital and cybersecurity: why Okta, CrowdStrike, CyberArk and others invest in cybersecurity startups

Private Equity (PE)

Private equity firms are financially motivated providers of capital focused on buying companies and stepping in to turn them around - increase sales, merge with other firms, and so on to maximize the value of the investment. While VCs primarily invest in early-stage startups with the potential to grow, PE firms buy established companies that have proven there is a need for what they offer, but who either struggled to maximize their potential, or who private equity investors believe can be worth much more after making some transformations.

Recommended reading: Game of Thrones in cybersecurity: data gravity, industry consolidation, platform play, private equity, and the great cyber gold rush

Follow the influencers: who impacts the demand for security tooling & the future of the companies

For security companies to grow, they need to expand their area of influence. One way through which this is done is by investing in relationship building, namely the functions known as Analyst Relations (AR), Government Relations (GR), Investor Relations (IR), and Public Relations (PR). In this context, the word “relations” is a shorthand for “influence”.

Analyst Relations

Industry analysts play an important role in the cybersecurity purchasing process. There are several reasons why that is the case, including:

The large number of vendors on the market makes it nearly impossible to research and evaluate all the options available

The fact that security products are very hard to test and their capabilities (especially as they relate to security coverage) are not possible to easily compare

Industry analyst firms play a unique role in the market:

Security vendors buy subscriptions which gives them access to the research, but most importantly enables them to spend more time with the analysts. The more time they spend with analysts, the stronger the relationship and the more analysts keep their solutions top of mind when customers come to ask for recommendations.

Security organizations buy subscriptions which gives them access to the research, but most importantly enables them to spend time with the analysts. They often come with questions such as "What tool is the best in the market for X or Y" and "How should I tackle problem Z in my organization?".

Given the number of vendors in the space, it’s no wonder that companies that invest in analyst relations are much more likely to be recommended as potential solutions to customer problems. This happens not because of some kind of underground deals, but because analysts are more exposed to their solutions, and therefore are much more familiar with the value they can offer.

Recommended reading: Gartner, Forrester and cybersecurity: a deep dive into the trends, challenges & the future of the notorious industry analyst firms

Government Relations

As I explained before, because the private sector focuses on maximizing shareholder value and increasing profits, without appropriate regulation and mechanisms for enforcement it will typically look to implement the minimum measures which allow it to achieve these goals.

Security companies understand that the government is the market maker: by legislating cybersecurity requirements, it produces the demand for new solutions. This is why the government relations (GR) field, although barely visible from the outside, is so critical to company success. Cybersecurity vendors are happy to lobby new regulations, frameworks, and compliance requirements because they help sell more products. The flow goes as follows: breaches lead to lobbying for new regulations, and this lobbying translates into legislative requirements, which in turn drive demand for cybersecurity.

Recommended reading: The government's role in shaping the future of cybersecurity

Public Relations

Public relations (PR) is a field focused on managing how others see and feel about a problem, brand, or company. In many ways, PR (influencing the public) is a big part of all other spheres of influence (government, analyst firms, investors, buyers, etc.). This is because all of us are first and foremost members of the public: if a CISO learns from the news that a security company is being sued by its competitor, or if an investor sees a stream of bad product reviews, the decisions they make may be affected by these events.

Investor Relations

Investor relations (IR) as a field is slightly different than the previous three as instead of influencing the demand for solutions, it generates the supply of capital. Investor relations focuses on shaping certain perceptions of the company. While it can be immensely useful for privately held startups, it is especially important for publicly traded companies.

Investor relations enable the company to:

Provide regular updates, progress reports, and other information consistently to build trust and foster transparency with investors.

Build close relationships rooted in collaboration and mutual support.

Make it easy for prospective investors to evaluate the company and make informed decisions.

Follow the talent: the fluidity of cybersecurity talent

In most industries, the academia, underground movements, public & private sectors, and other sides do not intersect: someone who spent decades working for the government will typically have a hard time finding a job in a corporate environment. That isn’t the case in cybersecurity where talent moves freely between different groups and types of employers.

What makes the situation even more unique is that very few people come into the security industry via the traditional “got a degree in cybersecurity and found a job” path. Instead, many start in IT, compliance and risk management, software development, military service, public service, research and industry analyst firms, consultancy and audit, and other areas. Cybersecurity is commonly a second or even a third career, so it’s common to meet people who in previous lives worked as musicians, psychologists, school teachers, and law enforcement officers, to name a few.

Although talent mobility is there, and people move from one pocket of the industry to another, they tend to gravitate to areas where they can be surrounded by those who share similar backgrounds. There is relatively little talent mobility between the military and industry analyst firms, hackers and security startups, or academia and cloud providers, to mention some.

The talent mobility is the strongest within the four categories:

Security practitioner (security analyst, security engineer, security architect, etc.)

Company operator (operations, marketing, product, sales, etc.)

Investor (angel investor, angel syndicate lead, VC, PE, etc.)

Policymakers (federal, state, think tank, intergovernmental organizations, etc.)

Moving within the category is relatively easy: although there are different types of investors, it’s generally easier for a VC to become a private equity investor than it is to join a startup as an operator. For a head of product at a security company, it’s easier to become a marketer than it would be to become a policymaker. Security practitioners are the most flexible - because there is a need for domain expertise in every area, they can move in any direction and become investors, operators, or policymakers. Successful operators have the potential to become investors. It goes without saying that these aren’t all the possibilities but the most common ones: there are certainly founders and security leaders who become policymakers, policymakers who become investors (based on my observation, they tend to focus on dual-use technologies), and there is at least one investor who became a security practitioner.

It’s important to keep these mechanics in mind when trying to build an understanding of the sector as depending on where your network lies, and what background you have, you may get a very different view of the field than people around you.

Follow the relationships: collaboration and coalitions

Nothing shows the segmentation of the security industry as well as various cybersecurity communities and network groups. Members of such groups share similar interests and therefore collaborate with one another a lot; at the same time, connections between different communities are sometimes fuzzy and at other times entirely non-existent.

Securing an organization requires an ecosystem of solutions, and cybersecurity vendors know it well. That is why they constantly look for ways to partner with others, be it for joint marketing initiatives (think co-hosted webinars or splitting the cost of events at major conferences), go-to-market strategies and distribution (bundling and cross-promoting their offerings or selling them as add-ons on the marketplace), threat intelligence sharing (sharing indicators of compromise), or technical simplification (agreeing to use a certain type of standard or a technical approach to make their products easier to integrate). Cybersecurity vendors exist in the constant state of “coopetition” - cooperation between competitive startups and enterprises by forming partnerships and alliances designed to benefit all parties involved.

Although from the outside, it might look like all investors are fiercely competing for the same deals, in reality, the relationships between them are much more nuanced. First and foremost, there is a strong, mutually beneficial collaboration between VCs and angels. Angel investors are often the first to hear about new companies, and they have a personal interest in having startups they invested in successfully raise the next round. VCs, on the other hand, are always on the lookout for new ideas, and being the top of mind for angels helps them to get into the good deals first. While many people understand the dynamics between angels and VCs, few have visibility into the collaboration and information sharing that happens between venture funds themselves. And, there is a lot: VCs share their thinking about different companies, help one another with due diligence, look for ways to co-invest, and so on. Not every fund is connected to every other fund: when fundraising, founders need to understand how different investor networks are connected, who talks to whom, etc.

There are plenty of collaborative communities in cybersecurity. Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs) are non-profit associations that bring together representatives of public and private sector organizations working in similar domains (i.e., healthcare, automotive, etc.) to gather and share experience, knowledge, and analysis about cyber and physical threats, including prevention, mitigation, and recovery. A variety of international organizations such as The Anti-Phishing Working Group and The International Association for Cryptologic Research bring together thousands of individuals, government agencies, and corporations to tackle critical issues of security. Professional associations which include The International Association of Privacy Professionals, The International Information System Security Certification Consortium, and ISACA, provide members education, professional development opportunities, and advocacy, while also taking part in recommending frameworks and standards. Hacker communities composed of ethical hackers foster some of the most innovative and collaborative networks of people sharing information and helping one another grow.

Each of these and other communities operates within the broader context of the security industry - the industry that unites these diverse networks into one big net. Formally, there may be little to no collaboration between each network, as most people are a part of only one or two communities. The glue between each community is super connectors, those who are a part of several groups simultaneously. A CISO, for instance, can be a member of an ISAC, a limited partner in a VC, a customer of a large security vendor, an advisor to a startup, and a reviewer of the standards in a professional association.

Closing Thoughts

Developing a deep understanding of the mechanics in the cybersecurity space isn’t a prerequisite for building a career in security, but it is most certainly needed to grow companies and get involved in shaping the space more actively. Security is a complex industry - having worked in fintech, e-commerce, retail, and wholesale before, I must admit that the number of players, the talent mobility, the parties influencing the buying process, and the ecosystem overall aren’t easy to make sense of.

In order to innovate, develop new business models, and find creative solutions to get products to market, entrepreneurs, VCs, and future founders have no choice but to seek out ways to build a deep understanding of how the business of security actually works. For this, visuals and charts highlighting the way the industry functions can be immensely helpful.

Nice one Ross! I love the systems thinking. Surely a Miro special too? 🦾