Getting Europe to become an active player in the global cybersecurity market: challenges, opportunities, and the way forward

Looking into the three-part challenge of building a cybersecurity company in Europe, and how the Old World can catch up with the US and Israel

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Learn how your company can sponsor Venture in Security: Sponsorship.

European cybersecurity market: a big promise

Securing people, businesses, countries, and their data is a global problem, so it would be very naive to think that the cybersecurity market is limited to the United States. Europe, in particular, presents an interesting case study as, despite a serious focus on data privacy, it is yet to realize its potential as a major market participant.

At first glance, Europe has all the key ingredients to make it a visible player in the cybersecurity space:

The EU functions as a single market made up of 27 countries.

The total value of all gross domestic product in the EU in 2021 was 14.5 trillion euros, just about the same as the GDP of China in the same year.

The European Union has historically been among the fastest to respond to the growing threats and emerging technologies by publishing strategies and white papers (the case in point is the EU directive about AI).

The European Union combined employs more software developers than the United States - a fact that is rarely talked about.

Despite all of these and many other factors, Europe has been lagging in both the adoption of mature cybersecurity practices and the growth of cybersecurity companies. As Hugo Nicolas of Axeleo Capital rightly observed, none of the top 20 cybersecurity companies are based in the EU.

I have met and continue to meet ambitious security startup founders from Europe, and I see how the odds are typically stacked against them from day one. In this piece, I am looking at some of the reasons why that has been the case, and presenting a perspective on the path forward for entrepreneurs and cybersecurity investors.

Challenges of the European cybersecurity market

An incredibly complex marketplace

It is tempting to see Europe as one market, but nothing could be further away from the truth.

First, even though most people, especially those working in the tech industry, speak English, the language barrier remains a challenge. Admittedly, this is more of a cultural problem than it is the language one: when evaluating products made in Europe, European buyers expect to see support for their native tongue, even though they are fine buying a product in English made in the US. The same is true for going through the sales process: when negotiating with a European company, a French buyer will expect to deal with a French native while a German CISO will expect to talk to a German reseller or a salesperson; the same requirements do not apply to American companies.

The cultural differences can be quite stark: what is considered normal as a part of the sales process in Italy, will not work in France or Germany, and vice versa. The customer demographics is different, as is the reseller ecosystem: in Germany, there are a lot of strong mid-size local companies; in France, there are many SMBs and several large firms. If a startup wants to establish a reseller contract in Germany, it can start by talking to mid-size resellers, but in France, it makes more sense to go straight away to large players.

Despite the presence of the pan-European governing bodies, matters of national security and defense are often viewed on a national level. This means that Germans would want to keep their data in Germany & work with local cybersecurity companies, as would businesses and governments in France, Netherlands, Belgium, and elsewhere. When storing the data isn’t the issue, deciding whom to buy from may be. Direct sales between different countries are hard, so most cybersecurity providers with pan-European ambition have to 1) meet all the necessary compliance requirements for every country they would like to enter, 2) make sure their product is available in the language of the country they are looking to enter, and 3) build relationships with channel partners who already have well-established relationships in the market. I have previously discussed that trust in the cybersecurity purchasing process has a national flavor; the European market is a textbook example of what that looks like.

Another factor that makes Europe hard to navigate is the complex legal system. Although European Union does a great deal of work to simplify doing business on the continent, the reality is that each country has its laws, regulations, and compliance requirements, neatly layered on top (or below, depending on how you want to look at it) the laws passed by the pan-European governing bodies.

The European Union is known for strict privacy laws and compliance requirements about seemingly anything that can be regulated - from doing business to building technology products. Naturally, this makes navigating the European market much more complex for outsiders, often fostering the “European market is for Europeans” mindset. What is interesting is that this emphasis on compliance is predominantly the result of lobbying from two countries: Germany and France. Earlier this year, Politico published a fantastic article illustrating that the countries making the rules about technology aren’t the nations leading on tech. The author states that “The future of tech innovation in Europe isn’t in France and Germany — it’s in Central and Eastern Europe” and offers stats that explain why countries like Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Estonia should be playing a more important role in shaping European tech regulation. I will be discussing how this applies to cybersecurity later in this article.

The absence of the early-stage funding

One of the biggest challenges I am hearing from European cybersecurity founders is the absence of funding options for early-stage ventures. This is not surprising: a quick look shows that there are indeed very few cyber-focused investors that support pre-seed and seed-stage companies, and those that do exist tend to be concentrated in a few markets. CyLon Ventures, a former cyber-focused accelerator turned professional investor, Cyber Club London, a cyber-focused syndicate, emerging funds such as Osney Capital, and established generalist VCs such as Nauta Capital, are all based in the UK. Then, there is eCAPITAL in Germany, Axeleo Capital in France, TIIN Capital in the Netherlands, Bright Pixel Capital and 33N Ventures in Portugal, and a few other funds. While this list isn’t exhaustive, it isn't a long one either. Of these investors, very few write checks to pre-seed companies; most focus on the growth stage, and a few can invest in the seed.

The funding gap at the pre-seed and seed stages isn’t as much about the absence of the early-stage VCs as it is about the absence of the angel ecosystem. This is because venture capital firms tend to come in at the seed stage or later. Early on, when there is no product, and the team hasn’t fully validated the market need, it’s the non-institutional investors that make all the difference. To build an ecosystem of angels willing to invest in cybersecurity companies, a few things are needed:

Security leaders who are innovative thinkers and early adopters ready to become design partners, and help entrepreneurs shape the direction of their efforts. We are starting to see the emergence of these groups - several visible cybersecurity leaders from Europe are members of the VIS Angel Syndicate, and many others participate in the above-mentioned Cyber Club London.

Founders who exited their startups, ideally in the cybersecurity space. Unlike Israel, where the exit of the Check Point gave rise to tens of different startups, provided capital for angel investing, and kickstarted the creation of the local ecosystem, Europe did not yet have a similar market creator. Although several notable European security companies did go public or were acquired, the region is yet to see the emergence of a full security ecosystem. This is to a large degree because of the absence of one single European hub for the industry.

Compared to the United States where taking risks and investing in a highly uncertain future is a part of the culture, most European VCs tend to be more conservative and risk-averse, often asking to see revenue, customer logos, and some - even detailed business plans before making decisions to write a check.

The absence of a large number of the risk takers willing to come in and support promising founders at the earliest stages of their journey is an issue, particularly because it’s at that stage where the local help is most impactful. When the startup has validated the problem, achieved product-market fit, and acquired some US customers, quite a few American investors start seeing it as a potential investment opportunity. Before that, however, local (European) angels, syndicates & VCs are the only viable funding option. Some founders of early-stage startups mistake general interest from US-based VCs for their desire to invest, and by doing so they often end up misallocating their most precious resources - time - and talking to venture investors who are unlikely to write a check anytime soon, instead of building the product and trying to get some traction.

Government financing options

Unlike the government in the US which acts predominantly as a regulator and market creator through legislating cybersecurity requirements, European lawmakers are much more involved in shaping the tech ecosystem. One of the ways they do it is by providing non-dilutive funding options to support local cybersecurity startups.

I have met many great founders who were able to get started because of government grants. Having said that, I think I have seen enough to conclude that despite the great intentions of lawmakers, if the founders are looking to build and scale a product company, more often than not grants turn out to be harmful to the long-term startup success.

A startup by definition is a high-risk endeavor that has less than a 30-50% chance to succeed but if it does succeed, it can offer great returns to both founders and investors. The issue with public funding is that it distracts founders from doing what they set out to do: moving fast to validate the problem, find the solution, and acquire customers who can benefit from it the most. Those who know that their runway is limited, and they have to make it work quickly, develop the level of customer obsession and bias for action that are imperative to the startup's success.

Government grants are rarely easy to get. Founders are often forced to study the regulations, spend many hours putting together a business case, gathering required documentation, putting together projections of future impact, and sometimes even forecasting the cash flow. While they are busy with all the bureaucracy, they are not doing customer discovery, not validating if there is a need on the market for what they are developing, not signing design partners, not onboarding customers, not building relationships with the investor community, and so on. This is harmful on multiple levels. First, government-backed startups can get a false sense of security thinking that they have more time to figure things out and failing to understand that their competitors are moving at a much faster speed. Second, they are more likely to continue building cool technology without validating if it is solving a problem someone is willing to pay for. They may think that once they build what they have envisioned, people will suddenly realize that they really need this tool, which in most cases doesn’t happen. Third, the requirements of most government programs do not end when the money is transferred to the startup’s bank account: there are typically reports to submit, meetings to attend, and results to show, all of which take the founder’s focus away from building the business. Moreover, government funding is like a drug: once the company has spent the time putting together the initial application and building relationships with some government officials, it becomes easier to do more of that, and subsequently easier to forget that the startup should be going out, talking to customers, closing sales, and shipping code.

Although I think that the non-dilutive government grants are likely to harm the growth trajectory of startups looking to become venture-backed companies, they may very well be a great fit for founders interested in bootstrapping and growing organically. I do not believe that every company needs to raise VC capital; in fact, most cybersecurity startups are not fit for the venture model. I think it’s important that founders understand what kind of company they are trying to build, and make decisions that take them in the direction aligned with their values and ambitions.

Lastly, it is worth noting that government funding allocated to accelerators and VC funds can indeed be a great way to support the ecosystem. The key here is how it is allocated and what startups are expected to do to receive it. If everything is done through an independently managed competitive process that evaluates companies as investments, with the full context of the commercial market, it can work well. However, most governments are uncomfortable delegating the evaluation to an entity that can give money based on the pitch deck and a few diligence meetings alone. To meet the high level of scrutiny and ensure that public funds are not misused, they end up creating bureaucratic programs that aren’t truly helpful to entrepreneurs with the ambition to build venture-backed players.

Another issue is the requirement that a startup that receives government funding has a certain percentage of customers based in the country that provides capital. This alone can prevent companies from adopting a global mindset, and focus on small markets instead which can be detrimental to their long-term success.

Differences in the mindset

I have previously discussed at length why compliance is not the same as security, and why it is critical to adopt a security-first mindset. Europe likes compliance, so much so that the desire to see the right boxes checked often outweighs the focus on practical yet necessary security measures. This focus on compliance over security means several things:

European companies are much more likely to invest in solutions whose value proposition lies in meeting a certain framework or a standard, as opposed to buying engineering-focused security capabilities.

An average enterprise is more likely to employ compliance analysts and security policy employees than security engineers, detection engineers, and other hands-on security practitioners.

Products that tackle complex technical problems typically grow much slower than their US-based counterparts that have a much larger potential customer base.

Another dimension along which European and American cybersecurity startup ecosystems differ is the prevalence of the product mindset. In the US, the vast majority of big cybersecurity players are product companies - think CrowdStrike, Palo Alto, Microsoft, Zscaler, Cloudflare, and others. Europe, on the other hand, has a large number of successful security service providers but relatively fewer cybersecurity product companies. Building and scaling products is hard, and those who have seen how it is done, or better yet - accumulated experience doing it, have a tremendous advantage. First-time founders with no background in launching products and taking them to the market are much more likely to struggle with moving fast and iterating to gain traction, or worse yet - become a victim of the “we will build it and they will come” mentality.

Another challenge European early-stage entrepreneurs are faced with is finding early adopters and design partners. Companies in Europe are known for being risk-averse and strongly prefer ideas that have been tried and tested elsewhere. More often than not, leadership in the cybersecurity industry is defined by who can claim a new market category, and this category creation happens when a large part of the US market is familiar with the new approach, and when US-based industry analysts have a new abbreviation ready to go. Until there is an established, most EU and UK-based companies are not interested in looking at what the startup has to offer. In other words, the European market is not seen as a category creator.

Last but not least, I have witnessed that European cybersecurity entrepreneurs are much more likely to think about building a company slowly while maintaining a good work-life balance and planning for organic growth. This is in contrast with American, and even more so - Israeli founders willing to sacrifice any resemblance of the so-called work-life balance to achieve their goals and grow as quickly as they can. It is critical to emphasize that 1) this is most certainly an overgeneralization, and I have met plenty of European founders with a strong bias for action, and 2) by no means do I suggest that working 24/7 is a way to go. However, it is important to look at the situation from the investor’s perspective: an average US-based VC is far more likely to bet on someone who is doing what is possible and impossible to get big fast, and whose only focus is to grow their business. At the end of the day, VC investing is about delivering good returns to limited partners, and that is what venture capital firms are optimizing for.

The three-part challenge of building a cybersecurity company in Europe

When we look at the competition in the cybersecurity industry globally, it’s hard not to realize that the odds are stacked against European startups from day one.

American cybersecurity players have a home-field advantage as they only need to succeed once - in their own market ( eventually they will need to go after customers in Europe, but that’s much easier to do if the company has already established itself as a leader in the US). A US-based founder would likely have a local network to line up some design partners from day one, and potentially even know some VCs willing to support them. Israeli founders also build companies for the US market from the inception: Israel is such a small ecosystem that local entrepreneurs choose to go where the money is instead. They execute the same well-known playbook that goes more or less as follows:

find a problem and validate that CISOs are willing to pay for solving it,

get a few local design partners,

raise pre-seed capital from Israeli angels,

build an MVP,

start selling to customers in the US,

raise seed from local VCs (ideally - YL or Cyberstarts),

build the product,

raise a big round of growth capital from US-based VCs,

come out of stealth, enter the American market as a powerful force, and start aggressively fighting for market share.

The story of European founders is typically very different as most entrepreneurs start by going after their local market. As a rule, a cybersecurity startup out of Europe needs to succeed three times: in its local market, in the European market beyond the country it started in, and in the US market.

Each of these three steps comes with its own challenges:

To succeed in the market where the company first starts, it needs to attract funding from local angels and VCs which, as I’ve described, is anything but easy.

To succeed in the broader European market, it needs to raise more capital from European VCs (can be somewhat easier than raising pre-seed/seed but not by a lot), translate the product into multiple languages, and establish distribution channels in countries and cultures that are fundamentally different from one another.

Succeeding in the US market is the hardest for several reasons. First, the way companies in the US buy security products is quite different from the way this happens in Europe, from motivations to the number of stakeholders involved in the process. Second, by the time a European player has successfully overcome all the obstacles and gone through the baptism of fire, the day it’s ready to enter the US it will realize that there is already strong competition from American and Israeli companies that did not have to deal with the same growth struggles, raised a lot of capital, and grew quickly. Third, to expand in the US, a European player would need to raise a lot of money, well beyond what the founders have done before. This can be an ordeal as most top-tier generalist VCs as well as their cyber-focused counterparts would have made their bets on US & Israeli companies already. Fourth, even if the company can deal with all of the above, it still needs to hire the right founding team in the US and build the operations in an entirely new market - a task that by itself isn’t easy.

To make it big in the inherently global marketplace, European cybersecurity companies have to get a big chunk of the US market. Alternatively, their best hope is to get acquired by one of the American behemoths looking to expand its offerings into the European market which they might have neglected to stay laser-focused on the US, or one of the few large European cybersecurity conglomerates.

Source: Wavestone cyber startups radars (Switzerland, UK, and France), and Internet research

Looking for future venture-scale cybersecurity startups in Europe

Although it may sound like everything is doom and gloom, I don’t think so. Europe has great potential to start playing an increasingly more important role in the global cybersecurity market. It comes with several advantages: entrepreneurs who are used to making the most out of limited resources and running lean (a critical skill in today’s economy), great employee retention rates, and some great talent. Despite all this, the path to European cybersecurity ecosystem growth is not going to be easy.

Starting with the global mindset

European entrepreneurs with the ambition to build global cybersecurity companies must start with a global mindset. This doesn’t mean “incorporating as a Delaware C-corp”; it means designing the company with the global DNA, instead of mirroring the culture of the nation the founders are from or based in.

I have observed that the smaller the country, the higher the probability that the startup coming out of that country will start as a global player. An entrepreneur building a company in France knows that they have 2-4 years to grow, and they can get to 10-20 million ARR without going outside of their own country. The flip side is that by the time they’d have grown to that level, the DNA of the company would be so much rooted in French culture that it would be hard, and often impossible to scale outside. The same is true for another major European country - Germany. That is why both France & Germany, despite being the largest and the most massive markets in the EU, are arguably the worst positioned for becoming global players: by the time they are ready to go after the US, they are faced with fierce competition from American & Israeli players and a deep conflict about the company's DNA.

On the other hand, founders from small European countries, especially those that have their own national language, are uncomfortable with the size of their market. Startups in Nordics (Norway, Sweden, Finland, etc.), Estonia, Lithuania, and others know that there is little they can hope for in their own markets, so if founders have any ambition to build a sizable business, they have to start global from day one. That’s how we got Nord Security (Lithuania), F-Secure (Finland), Outpost24 (Sweden), Logpoint and Heimdal (Denmark), Binalyze and Veriff (Estonia), Arcanna.ai (Romania), and other players.

The UK is an odd case because the direction of UK-based cybersecurity companies will largely depend on the choices of their founders. Entrepreneurs in the UK have the most access to funding compared to their EU-based counterparts, and UK investors are much more open to playing big and taking risks. The culture, combined with the absence of any language barriers, makes UK-based companies likely candidates for going after the US market quickly. On the other hand, since the UK does have a decent market on its own, sometimes I see founders stay local for too long, missing out on the potential to play bigger in the US.

Starting global means being open to hiring the best talent from different countries, and not limiting the ambition to Europe. It also means building an understanding of the US market early and acquiring US customers as soon as possible. This is critical for two reasons: a) American enterprises want to see local (US-based) reference customers before committing, and 2) US-based VCs typically want to see revenue from US customers before they will actually consider investing. For engineering-focused companies, acquiring US customers is typically much easier compared to those that are more on the compliance side as many software developers in the EU work for American firms, either directly or via the satellite offices.

Developing a pipeline of cybersecurity startup founders

To attract funding, the European cybersecurity ecosystem needs to demonstrate a pipeline of promising cybersecurity founders. Note that I am not saying that Europe does not have great security practitioners - on the contrary, it does have a great talent ecosystem. What Europe is lacking, in my view, is a clear pattern for recognizing them.

In Israel, investors see the 8200 and IDF service badges as a strong background for future first-time founders. In the US, the same weight has the credentials of being an alumnus of FAANG, an early employee of venture-backed unicorns such as Uber and Cloudflare, a graduate of Stanford or Harvard, and to a degree a tenured employee of the three-letter agencies. Since early-stage VCs invest in people, they are trying to pattern match and look for signs that the first-time founders have met some bar, or accumulated some experience that will set them up for success (this is less important for repeat founders with existing track records). In both Israel and the Bay Area, it feels like almost everyone is a founder, and there is the gold dust that rubs off when people talk, network, and decide to build something new.

At first glance, Europe does not seem to have an obvious founder factory. Moreover, because many people in the EU work for the satellite offices of American companies, VCs in the US think that relatively few get exposed to what it means to build a successful startup.

While that used to be the case, I think it is not true anymore. I think today we are witnessing precisely that - the formation of the promising European cybersecurity founder pipeline. While the region as a whole is still drowning in a compliance mindset, security practitioners who work in high-growth European unicorns know what it takes to actually secure the infrastructure. Moreover, security professionals from companies like Monzo, Revolut, N22, Klarna, Rapyd, Hopin, Mollie, Mambu, Qonto, Contentful, GoCardless, and other European fast-growing high-scale companies have seen how products are built. Many of them had good exits, and many have built networks to get credible entrepreneurs with impressive track records on their cap tables as angel investors.

I don’t know to what degree this hypothesis will turn out to be true; only time will tell. I have met many great people with experience working at large European service providers and governments. The challenge many of them keep running into has to do with building products: that’s not something they have typically been a part of, and therefore know how to do. This lack of experience with product, however, is not a challenge for building good, sustainable companies that solve important problems. And, it is most definitely not a gap that can’t be closed: the same issue used to impact the companies coming out of Washington–Baltimore, but in recent years thanks to the work of players such as DataTribe and MACH37, it is much less true.

Solving the funding gap

A lot has been said that to produce great cybersecurity companies, Europe needs funding. I am sure there is truth in that: if more entrepreneurs get funded, the chances of more of them succeeding will naturally increase. However, I don’t think that raising the next generation of European cybersecurity companies is as simple as giving companies a lot of cash.

First, let me state this again: in most cases, for founders interested in building venture-scale startups, government grants are not a viable solution. Companies who choose to go for it end up spending time and effort going through the lengthy application process instead of moving quickly, validating the idea, and acquiring customers. The support provided by the government can foster complacency and distract from the fact that the solution to the lack of funding isn’t giving grants but building conditions that attract investments, from both internal and international players. This includes simplifying legal and regulatory requirements, creating attractive tax incentives for individuals and corporations, and the like.

Ultimately, we have seen well that it’s not the capital that attracts great founders, it’s founders that attract investors. VCs will always go where they can make money and generate higher returns for their limited partners. Following the exit of Check Point, and the subsequent rise of the Israeli startup ecosystem, many international (especially - US) investors ventured all the way to Tel Aviv in search of great companies. Europe has had some cybersecurity success stories, but none of them - are as impressive in terms of the ecosystem impact as the story of Check Point. To a degree, it makes sense: Israel is a small community, and since everyone is connected, and shares culture, language and drive to make big things happen, people supported one another which ended up compounding. I think something similar could happen in Europe; it would likely not be as explosive, but it would still have a big impact. For that to become a reality, we need to see more European founders reinvest a portion of their hard-earned money back in the cyber ecosystem. And, we need some cybersecurity entrepreneurs to start their own VC firms to support fellow founders. I am optimistic that we will see all this happen in the next decade.

Establishing a European success playbook

European cybersecurity startups have no choice but to start writing their own success playbook. It’s very likely going to look different from that of the US and Israeli founders, but they need to do it regardless. I do not operate in the European market, so most of my learnings come from advisory work and countless conversations with security practitioners, entrepreneurs, and investors from all over the globe. If I were to try and draw something on the napkin, I would think of the following:

Raise capital from European, and if possible - some US angels to build the product. Don’t obsess about American investors too early, but if there are people in your network from the US - absolutely go for it. At this stage, talking to the US VCs might not be the best use of the founder’s time as they are unlikely to invest (although most will be happy to talk - learning about important problems and building relationships is a big part of their job). Note I am not saying that a US VC will never invest in a European company: if the business fundamentals & traction are there, and the company is built with a global mindset, then it is possible. However, a founder is better off focusing on building products, signing design partners, and getting some traction instead.

Relentlessly cultivate relationships with the US customers: both directly, and through the European branches of the US companies that may be more accessible and willing to try the product to start.

Consider expanding to the US at Series A. For that, you will need to raise a solid round (think $15-20 million); find a US-based VC to lead the round. Most startups plan to go to the US last: they want to have a solid footing and use their clients with US presence (multinationals, etc.) as reference points for American prospects. With this approach, by the time the company is “ready”, there are already too many strong competitors on the ground, and the chance for land grab is lost. Although this isn’t going to be easy, the earlier the company can start going after the American market, the less likely it will get left out and out-competed by its US & Israeli counterparts.

Pick the right founding teams for the US; the best way to do it is to start by learning from the mistakes of fellow European entrepreneurs. Finding the right people willing and ready to execute is critical; the US expansion isn’t just about hiring a very expensive head of sales. Keep in mind that entering the US market is very costly, and many don’t get it right the first time. By the time it’s clear something is not working, it can be too late and the company has to go back or risk the capital and try again. Not planning ahead can cost founders dilution, capital, and execution.

Assume that what worked well in Europe is not going to work in the US. Learn, iterate quickly, and adapt your go-to-market, product, and team mentality to the reality of the US. In the EU, startups tend to compete on products as European corporations will pay a higher price for the solution that fits their stack. In the US, it’s the cost-benefit-based approach: the company needs to show the value it brings and articulate the return on investment.

I don’t know if that’s the right approach, as I haven’t done it myself, and I haven’t spent enough time validating it with those who did. However, it is clear to me that waiting until the company is ready, only to learn that there is little space in the US market for a new entrant is not a good idea. The problem of international growth has attracted a lot of attention in the industry with some VC firms such as Atlantic Bridge building their value proposition precisely around providing cross-border value add and expansion capital for technology companies.

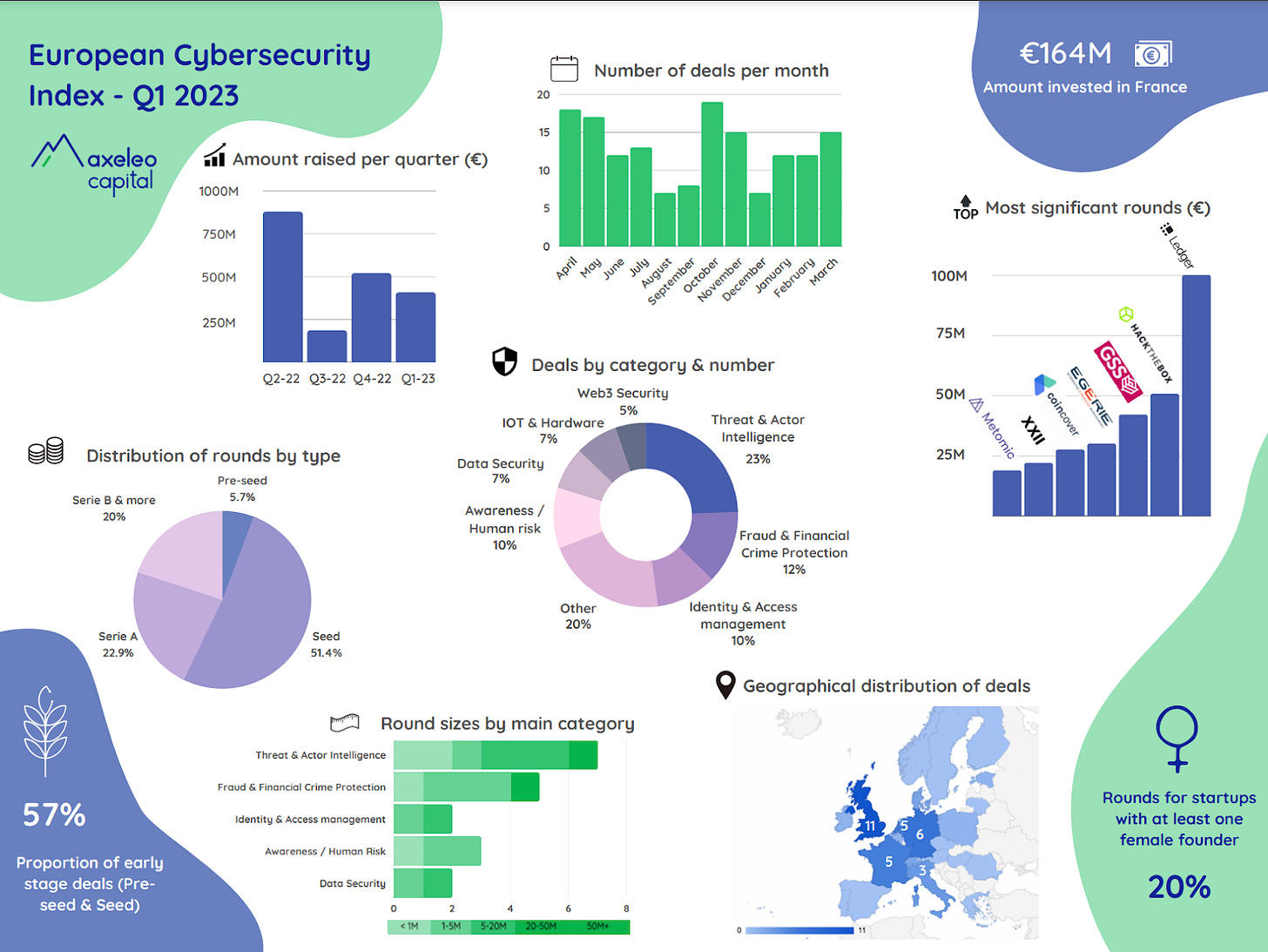

Source: European Cybersecurity Index by AXC - Q1 2023

Closing thoughts

Despite all the challenges, I believe Europe has great potential to become a leading power in the global cybersecurity market, in line with the US and Israel. For that to happen, many challenges need to be overcome. European founders need to build companies with a global mindset and international ambition, local investors should become less risk-averse, and companies should start to plan their expansion into the US earlier.

Today, the war in Ukraine is changing the European take on security, making it clear that having a checkbox from an auditor is not the same as being secure. Moreover, as security is becoming a priority, we see more and more cyber-focused investors - angels, VCs, family offices, and the like enter the European market. Meanwhile, tenured venture capitalists with experience investing in security companies are raising their funds. The European landscape is evolving, and I think that the next five to ten years will show if the region will be able to realize its potential or remain on the periphery of the world’s biggest cybersecurity markets.

Very good article. What is missing to close the analysis are two fundamental aspects related to mentality and legislation. From a mentality point of view, being Europe lacking behind USA in technology, in the majority of the countries software engineers, software architects, product managers or anyone working in IT are considered as 'technicians' on par with electrician. It is a chicken and egg situation - because we are seen as 'electrician', or bizarre IT guys, we don't have the credibility to attract investments - on the other side of the coin, because Europe lacks behind the potential added value of IT companies is not fully appreciated nor is the hard work of the people that have studied the field. It is not unusual, and I heard many times, listening to global townhall for companies with the HQ in Europe to 'complain' about Europe lacking behind, yet internally not having a clear career path to develop engineers above the individual contributor role and for any managers role outweighing any even minimal technical knowledge by the pure ability of managing people, abilities often matching with a management style detrimental to knowledge worker i.e. command and control. Last bit not mentioned are the legislations related to failure, and the mentality around it. In Europe, whoever dare try to build a whatsoever company without having a large safety net or being child of a family which is already a company owner is seen as a fool. Doing so is not encouraged, it is condemned as arrogance rather than being appreciated as courage. If more so the venture fails, as many startups do, the legislation around it is troublesome and your career credibility and potential reemployment or opportunity to attract funds is destroyed, you are basically tainted as a Looser for your entire life. The other side of the coin, considering that from failure you could have learned a lot and so avoid further mistake is not considered at all. If you finally look at the startups created in Europe you will also quickly find that the creators are often tied to international environments, academy, to open source, already wealthy or in general, in some way or another, they all had an heavy exposure, if not even their social circle, is going to be largely outside Europe.