Caveat emptor: product-led growth in cybersecurity can be a great idea, but it can also hurt or even kill security startups

Discussing my learnings about PLG in cybersecurity over the past year, reasons why it can be a great way to grow security companies, and how PLG can really hurt and even kill security startups

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Last week I crossed a great milestone - over 1,000 copies of my best selling book “Cyber for Builders: The Essential Guide to Building a Cybersecurity Startup” have been delivered by Amazon. This book is unique as it talks about building cybersecurity startups. It is intended for current and aspiring cybersecurity startup founders, security practitioners, marketing and sales teams, product managers, investors, software developers, industry analysts, and others who are building the future of cybersecurity or interested in learning how to do it.

Those who have been reading Venture in Security for a long time will likely remember me as an advocate of product-led growth (PLG). I have been very outspoken about the need for cybersecurity companies to become more open about the value they bring, and make it easier for security practitioners to try their products without having to attend multiple mandatory demos and get pre-qualified.

My last article about product-led growth, PLG is not a boolean: practical advice for cybersecurity startups looking to embrace product-led growth, was published in December 2022. Just over a year later, as I was speaking on the panel at the CyberMarketingCon 2023 alongside Jessica Crytzer and Steve LaChance about this exact topic, I realized that it’s time that I shared some of my recent learnings about product-led growth in cybersecurity.

In this article, I am going to do just that.

Source: Panel on PLG at CyberMarketingCon 2023

A brief recap: fundamentals of product-led growth

For people unfamiliar with the concept of product-led growth, here is a quick summary. Historically, software products were sold to businesses via traditional sales channels, by having a salesperson do a demo, pre-qualify the prospect and decide if they meet the criteria to become a customer, and plan a Proof of Value (POV) evaluation. After a successful POV, the process of contract and pricing negotiations would follow, after which the customer would hopefully sign a long-term contract and roll the new solution out in their organization.

In the past decade, this rigid, structured purchasing process has evolved to become more friendly to buyers. Prospects are now increasingly able to get started with new tools without having to attend mandatory demos or negotiate long-term contracts. Since companies are starting to offer self-serve ways to test their solutions, anyone can create a free account, start using the product, and only then, when they are satisfied with what they see, initiate a discussion about potentially buying it for their company.

The change in the way software is being bought created an impressive opportunity for startups. Some of the largest companies that became public, sold, or are valued at billions of dollars in the past decade are product-led. This includes Slack, Zoom, Shopify, HubSpot, and hundreds of others.

Source: OpenView

For many years, there has been a debate about whether or not product-led growth can be a fit for cybersecurity startups. As of the time of writing, there are no good examples of cybersecurity startups that were able to succeed in growing into a public company or getting an impressive exit (say, above $500M) by relying on product-led growth.

Last year was not kind to the very organization that coined the term “product-led growth”, the VC firm OpenView. OpenView has failed to deliver on its investments and ended up having to go into a “voluntary suspension” mode before it decides what to do next. That said, the story of OpenView is irrelevant to our discussion and to the future of product-led growth in general. The success of any growth strategy is measured by its ability to enable companies to grow, not by what happens to the party that comes up with the term that describes it.

Where my thinking about product-led growth has stayed the same

It has been a year since I published the last article about product-led growth in cybersecurity.

I have always been a pragmatist, and my thinking about product-led growth is not an exception to this rule. The question to me has never been “How to make this thing work in cybersecurity?”, but instead “What can we do in cybersecurity that has the potential to move the needle in growth?”. As I explained in the past,

“The purchasing process in cybersecurity is heavily based on trust. This means that:

Individual contributors can recommend security products but cannot get them adopted without the senior leadership signoff because of the high levels of risk.

Companies evaluating security tooling offered by a startup will most definitely have questions, are likely to request documents like SOC2 compliance evaluation, and will want to meet someone from the leadership team to gain confidence in the company's future. Implementing cybersecurity products is costly, and while PLG promotes the idea that a customer would "sign up in a self-serve manner, add their credit card and start paying", any serious security team will want to have confidence that your product will not disappear three months after the rollout.

Making it easy for customers to evaluate the product without having to connect it to sensitive production data can make a huge difference in adoption. Optimizing onboarding for PLG cybersecurity startups is much more than reducing the number of clicks and screens. It is about providing demo content, making technical documentation readily available, and having a customer support team to answer any questions that will most definitely arise.

Many cybersecurity products, including those built for defense, can be leveraged by malicious actors for the offense. I have previously discussed a similar conundrum in the context of open source (the two debates about open sourcing offensive & defensive tooling), and it can be even more complicated for commercial tooling. Vendors are responsible for making sure their products are not giving the threat actors who aren’t known to abide by terms and conditions, an easy way to break into the victim’s environment.” - Source: PLG is not a boolean: practical advice for cybersecurity startups looking to embrace product-led growth

My thinking along these points has not changed. Security teams indeed aren’t just looking for ways to put in their credit card and start paying for the new tool. The purchasing process in cybersecurity is complex, and there is no way around this complexity, with PLG or without it. I continue to believe that making the products open and accessible is the path our industry should be taking for the long term. And, I stand by my recommendation for startups to at all costs avoid jumping into implementing PLG (or any other strategy for that matter) all-in, but rather do it slowly while assessing the impact it is having on the company's bottom line and making adjustments as needed.

The big shift in my stance on the role of product-led growth in cybersecurity

Although my understanding of the challenges and opportunities product-led growth brings to cybersecurity has largely remained the same, some learnings pushed me to evolve my thinking about PLG in cybersecurity. What has indeed changed significantly is the way I talk about PLG and its potential for the industry.

The big shift in my stance on the role of product-led growth in cybersecurity is that I now prefer to talk about the reasons not to think about product-led growth and the ways in which it can hurt security entrepreneurs first, before discussing its potential benefits. This change is not accidental. I came to realize that every time I would explain the complexity of PLG, why it is not gaining adoption in security, and why security practitioners can’t and won’t just put their credit card in and start paying, founders would immediately gloss over all the tough questions, and only hear what they wanted to hear.

It is hard to blame security entrepreneurs and startup leaders for wanting to focus on what sounds like a promise of growth and close their ears to the other side of the equation. In my opinion, two factors are causing this issue. First and foremost, the vast majority of cybersecurity startups are not growing. Reasons are plenty, but the outcome is always the same: VCs are looking to see the revenue numbers go up, and founders are struggling to figure out what else they could be doing to make that happen. When someone mentions product-led growth and how it enabled the creation of multi-billion companies in other industries, their eyes light up. At that point, they are no longer thinking straight and all they are hearing is why this magic solution is “100% going to work”. Second, there is a lot of sentiment on social media such as Reddit and LinkedIn that people are tired of gated solutions. While that is indeed how many in the industry feel, there are several challenges: 1) it is hard to understand if these “many” are a loud minority or a big chunk of the market, 2) it’s unclear if people who are looking to access security tools self-serve have the authority to buy them, and 3) it’s hard to know how many of those who are vocal about security products being inaccessible are actually buying tools self-serve. Moreover, many founders are former practitioners, and the memories of them being unable to try a product they were interested in are still fresh. Lastly, too many people forget that there is no such thing as a “security market”: the sentiment of those working in compliance doesn't apply to people doing identity, which is in turn different from what teams focused on endpoint security are feeling.

Either way, too many founders, product, sales, and marketing leaders in security see product-led growth as a magic wand that will finally make it possible for them to grow the company. This is not just because they are being naive; often, before getting excited about PLG they would have exhausted all other options to get the numbers go up and to the right, so product-led growth is the only thing they haven’t yet tried. To temper their excitement, I now start by explaining all the reasons why PLG in cybersecurity is a bad idea.

In addition, I am now loudly emphasizing that the only form of product-led growth in cybersecurity that works is product-led sales (PLS). Again, I have always been clear that product is just a supplementary growth channel, and without a strong sales function, cybersecurity startups cannot grow. Over 1.5 years ago, I said: “Cybersecurity is an incredibly crowded space with some segments being in a better place than others. Companies embracing the PLG approach cannot afford to sit and wait until people realize the value and convert on their own. That should be the end goal, but the reality of building the business is that PLG startups in security have to keep moving forward; combining PLG with product-led enterprise sales is a key to success”. More than ever before, I am now convinced that in cybersecurity, product can be a great way to generate leads, but a strong sales motion is a must. People aren’t just going to “upgrade” on their own: a sales team is needed to guide them through the process. Moreover, the vast majority of revenue will continue to come through the traditional sales path. Product can become a great supplementary growth channel but it is not going to be the way the company gets to the milestones it needs. In the past, I was more optimistic about the ability of product-led growth to become a large revenue generator for cybersecurity startups than I am now.

All this has turned me into a devil’s advocate: while I am still, more than ever, convinced of the value of building practitioner-focused tooling, I am careful about the way I talk about PLG/PLS. Not to discourage founders and startup leaders but to temper their excitement and make sure that people interested in this strategy will step back, pause, and think about what they are doing first.

Why cybersecurity lags behind in embracing product-led growth

In my opinion, there are three major reasons why cybersecurity lags behind in embracing product-led growth. Each of them can be mapped to the three categories of tools that have seen a lot of success in embracing the PLG strategy.

The first category of products that have seen a lot of success in implementing product-led growth is productivity and collaboration software. Companies such as Canva, Airtable, Notion, Zoom, Slack, Calendly, Figma, and others all fall under this category. The way bottom-up adoption has worked for these tools looks as follows:

An individual would discover the tool while looking for ways to solve their own problems. For example, a person who is looking for ways to better manage their tasks would find Asana or Monday.com.

An individual would get started with the tool for free. For example, I have been a heavy user of Canva, Calendly, and Notion, all without buying a subscription. Some people would later upgrade to the paid tier (I did that with Calendly, but not with Canva or Notion).

After realizing the value of the tool and falling in love with experience, an individual would recommend the tool to their employer, and champion its adoption company-wide. For instance, someone who has actively used Notion or Zoom would want their employer to adopt it as well.

The critical factor that made productivity and collaboration software suitable for product-led adoption is the fact that the core problems these tools solve are similar for different types of customers, be they individuals, SMBs, or enterprises. For example, the core functionality of the project management tool Asana is the same regardless of the type of customer. The enterprise using Asana would just need some additional features such as team and department-level capabilities, single sign-on (SSO), the ability to access audit logs, and role-based access control (RBAC).

This is not the case for cybersecurity. As I explained before, “Although cybersecurity is everyone’s problem, security companies don’t get the ability to build for individuals and move up to enterprise customers, and vice versa. There are some exceptions such as password managers, but for the most part, a solution needed for individuals (all-in-one personal security) looks very different from what’s needed for SMEs (all-in-one business-level security) which is even more different from what’s required by the enterprises (advanced solutions to specific problem areas such as endpoint security, cloud security, etc.). Security startups have no choice but to pick a market segment they want to focus on from day one”. If an individual were to adopt Aura or SquareX, they would not be able to get their employer to also adopt them since businesses need different kinds of solutions - asset and vulnerability management, endpoint and cloud security solutions, etc., not an all-in-one “keep your family safe” tools.

The inability of cybersecurity solutions (except password managers & VPNs) to offer the same tool to companies and individuals makes them unsuitable for PLG compared to their productivity and collaboration counterparts. Moreover, individuals don’t generally want to buy security tools, and they are most definitely not used to going on social media to shout out security vendors or recommend security apps to their friends. This reality makes cybersecurity products unsuitable for viral growth.

The second category of software tools that have seen a lot of success with product-led growth is developer tools featuring companies such as GitHub, GitLab, and Postman. Fundamentally, the way bottom-up adoption has worked for these tools looks as follows:

An individual would discover the tool while looking for ways to solve their own problems and start using the product for free. For example, an engineer who was working on building a side project would start using GitHub.

After realizing the value of the product and falling in love with the experience, an individual would recommend it to their employer, and champion its adoption company-wide. For instance, someone who has actively used GitLab would want their company to adopt it for building software.

In my view, the key factors that made the bottom-up adoption of developer tools possible include:

A large number of software developers globally.

The fact that software developers build code outside of work, and therefore a lot of the problems they would experience at work are also problems they need to solve for their own side projects.

The fact that in most organizations, software engineers are empowered to do their own research, and recommend products that can be adopted by the company. In many companies, software engineers are also allowed to use their own tools, and even given a budget for that.

Security practitioners, with some exceptions, do not share the same characteristics. There are fewer security practitioners than there are software engineers, and as a result, the pool of potential users for security tools is small. More importantly, the vast majority of security practitioners are not solving their own problems with commercial security tools outside of work. While almost every software developer has built something on the side, not every security practitioner has a home lab or an idea they are toying with on the side that would require the use of a security tool. This also varies by discipline: people who are working in endpoint security are more likely to have a home lab than those in, say, vulnerability management or identity and access management. The percentage of security practitioners who are empowered to evaluate tools and recommend different solutions to their management is substantially smaller than those of software engineers. And, they certainly don’t get company budgets to choose which security tool they would individually like to use.

Another important factor to note is that software engineers are always building something, and therefore, they are constantly looking for ways to make that process easier. The vast majority of security practitioners are not builders. Those who possess an engineering mindset, such as security engineers and architects, experiment with different tooling, contribute to open source projects and even build their own. They are precisely a segment well-suited for product-led growth. Other categories of security practitioners that could be a fit for PLG are those who spend their weekends experimenting with different technologies. But, as of today, most people in the industry are implementers and operators, not builders, and most security tools require a proper environment where they can be tested.

I think that one day, cybersecurity will get the critical mass of practitioners around which security companies design their bottom-up go-to-market strategies. I am convinced that we are also starting to see a rise in security engineering approaches in the field. There is a growing percentage of people in the industry who are early adopters of this approach, but the time when they constitute a critical mass has not yet come. We should be patient: software engineering as it stands today is a well-formed and highly mature professional discipline, but it hasn’t always been this way. It has taken us several decades of training engineers, along with movements of Agile, empowering teams, and other changes to get where we are today. Given that cybersecurity is a much younger discipline, we should learn to be patient and adjust our expectations while continuing to push the industry forward.

The third category of software tools that have seen a lot of success with product-led growth is customer engagement and back office tools such as Intercom, Loom, Mailchimp, and HubSpot. Some of these (such as Loom) can also fall under the previously discussed bucket of productivity and collaboration software. Categorization issues aside, what made these products suitable for the PLG motion is that the data they require to work is well-understood, tightly scoped, fully transparent, and entirely under the control of the customer. For instance, Mailchimp only needs an email address to send emails, but customers can include the first and last names of the receivers or any other information they choose. Even tools such as Stripe handle well-scoped parts of the value chain, in this case, processing payments.

Cybersecurity tools, on the other hand, require access to the most private and confidential data and often gain permission to make powerful changes in customer environments. To get value from these products and make it possible for them to detect and respond to threats, customers need to have a high level of trust - much higher than can be achieved while going through a highly optimized, quick signup flow.

Product-led growth and or product-led sales can hurt cybersecurity startups

I have written extensively about the benefits of product-led growth (PLG) and the opportunities it creates. However, PLG and product-led sales (PLS), if not done well, can hurt cybersecurity startups. In this section, I am going to discuss several ways in which that can happen. Note that this is not an exhaustive list of constraints founders and executives need to consider when discussing the feasibility of PLG/PLS for their organizations.

PLG can undermine the startups’ ability to sell through the channel

As I have discussed before, more than $9 of every $10 in cybersecurity is sold to enterprises via partners. Channel partners, namely consultancies, value-add resellers, integrators, and service providers are how the largest enterprises buy security products and services. Any enterprise-focused cybersecurity startup looking to grow beyond $5-10M in annual recurring revenue has no choice but to keep the channel in mind when planning its go-to-market.

The early product-led growth effort will not necessarily hurt the startups’ ability to sell through the channel. That said, making the product pricing public and listing it on the company website is likely to. For the channel to resell whatever the company is offering, it needs to be able to make a good margin. If the solution is too inexpensive, the channel’s salesforce will be incentivized to push the offerings from the company's competitors as they are more likely to provide it with the shortest path to hitting the quota.

PLG can undermine the startups’ ability to close deals with enterprise customers

When selling directly to enterprises, there are a few factors startup founders need to keep in mind. First and foremost, enterprises have processes for procuring new tools, and someone can't bypass them simply by inputting their credit card and deploying the tool across the company. Steps like getting signoff from legal, compliance, and finance are a part of the journey.

What may surprise some founders is that having their enterprise tier pricing public on the website is likely to make their lives much more complicated. The enterprise procurement teams have the mandate to always negotiate a discount. Since people who do this work are being evaluated on the depth of the discounts they are able to get, they are going to be happier if they get the total price down from $100,000 to $60,000 per year, than they would be getting it from $70,000 to $50,000. In the end, what matters more is not so much the final price as it is the discount percentage.

Startups that list their enterprise pricing can do themselves a great disservice. They may lose the ability to be flexible in negotiation, and more importantly, become unable to offer discounts necessary to close a contract smoothly.

PLG can cannibalize the revenue the company could have achieved through traditional sales

Product-led growth can cannibalize the revenue the company could have achieved through traditional sales. When the prospect goes through the traditional sales process, the sales team is able to understand their needs and recommend solutions that most comprehensively address these needs. It is quite possible that if the same buyer were to onboard in a self-serve manner, it would just opt for the cheapest tier of the solution. When that happens, the customer may end up with a level of protection lower than what they need, while the company would lose the ability to earn revenue by offering additional value.

PLG can create problems for companies bringing new ideas to the market

When a cybersecurity startup is working to bring a new idea, new concept, or new technology to market, often referred to as category creation, its number one goal is education. Founders need to look for ways to learn about the market and educate potential buyers, partners, and industry insiders about the problems they are solving.

There are several reasons why PLG can be a particularly challenging go-to-market for startups solving problems that aren't yet well understood. First, if the target market of the startup is not aware of the problem, or doesn’t know how to phrase it, people are unlikely to be proactively looking for solutions, let alone signing up for new tools. Second, self-serve experience removes an opportunity for learning as founders won’t know what users who created accounts came for, who they are, and what assumptions they had when they created an account. Maybe, they are potential customers who found the company through word of mouth. Or, they could be students curious about new ideas. Options are plenty, and if founders lose the chance to talk to prospects, they are likely to miss out on important insights. Worse yet, they won't usually get an opportunity to learn why people didn't adopt the tool. Last but not least, if the prospect isn’t familiar with the new technology, it’s less likely they will be inclined to buy it without guidance from sales.

PLG can make it possible for bad actors to use the product for malicious purposes, or reveal the “secret sauce” to the competition

Having the product freely available in a self-serve mode can make it possible for bad actors to use it for malicious purposes. It is worth noting that those who truly want to get access to a security solution will always find a way to do it, but it doesn’t mean that making the job of bad actors easier is the right way to go about it. Companies considering making their products freely accessible must think if some functionality should not be made available to users whose affiliation and motives have not been verified. This is especially relevant for startups in the offensive security space.

Having a fully accessible product can also make it easier for the competition to gather intelligence about what the company is working on, or even reverse engineer its “secret sauce”. I don’t personally think this is an important concern: if a startup’s competitive advantage can be challenged simply because someone has access to their tool, I think the company has bigger problems to worry about. That said, depending on the stage of the startup, it may indeed be an important factor (say, if the startup is still in stealth mode).

PLG can cause a startup to lose focus on building capabilities that matter

When anyone can create an account and start using a security tool without having to go through the sales process, it invites product feedback and ideas from people who may or may not match the company’s ideal customer profile (ICP). While having more feedback to work with is great, to remain focused the startup will need to find a way to triage, prioritize, and evaluate user suggestions. Some people may be utilizing the product in ways it has never been designed to be used, or requesting one-off features that would not translate into useful capabilities for other customers.

It is not uncommon to see cybersecurity founders and product teams get excited about ideas and suggestions for cutting-edge, advanced features, and immediately jump into building what users ask for. This is a mistake as not everyone’s feedback should be treated the same. An idea that comes from one of the startup’s largest customers should not necessarily be weighted and prioritized the same as a suggestion from a student using the tool in their home lab for free. Without ruthless prioritization, the startup can lose its focus and the ability to execute.

PLG can cause startups to lose potential sales opportunities

Although having the ability for anyone to create an account and get started with the product in a self-serve manner can be a great thing, it can also cause startups to lose potential sales opportunities. If the product is too complex, or if it is too different from what people in the industry are used to, it can cause new users to get confused and churn. Moreover, if the solution asks for too many sensitive permissions or requires confidential data to get started, it is also likely that new users will abandon it without moving forward. And, once people decide that the solution is not a fit, they rarely give it a second chance.

When the company is not yet a household name and the level of customer trust is low, when the approach it is proposing requires additional explanation, or when the product requires access to sensitive data in order for it to demonstrate value, requiring prospects to attend a demo can be the right thing to do. Having a 30-minute long live interaction can enable the startup to explain its point of view, better understand the customer needs, set the stage for trusting relationships, or assist the prospect with configuring their demo environment. None of these problems can easily be solved in self-serve mode.

PLG can lead to false hopes and an illusion that the pipeline is bigger than what it actually is

Sales teams usually have a good idea of what the sales pipeline looks like, and what deals can expect to close by the end of the month, quarter, or year. Of course, things rarely go as planned, but the uncertainty is typically somewhat predictable.

PLG can lead to false hopes and an illusion that the pipeline is bigger than what it actually is. When a user whose email address matches the domain of a big company signs up, that may get the team too excited, too distracted, and potentially even disappointed when it turns out that that person was just curious if the tool could be a fit for their side project, or just wanted to see what the user interface looks like.

PLG can lead to other challenges, too

This list is by no means exhaustive as product-led growth can create other challenges for cybersecurity startups.

If you want to hear a real-life story about how PLG hurt a startup, check out this blog from Zachary Dewitt titled "Freemium Really Hurt Our Business" - A Must Read from Equals CEO.

Thinking about product-led growth from the first principles

I would be delighted to conclude this article by offering something definitive, flashy, and strongly worded like “Doing PLG the right way”. The problem is, I don’t think there is such a thing as “the right way”. Instead, I am going to share some ideas to help you think about product-led growth from the first principles.

It would be a mistake if I were to start by offering specific recommendations. Instead, let’s agree about what we want the ideal PLG implementation to look like:

We want it to expose the product to the subset of security practitioners who are interested in trying and testing it.

We want to convert anyone who creates an account into paying customers, or at the very least, vocal champions of the product.

We don’t want people who sign up for the product to churn because they either don’t understand the value, find the product too complicated, or for any other reason.

We don’t want PLG to hurt our ability to sell through the channel as that’s where 90% of the revenue comes from in the enterprise channel.

We don’t want it to hurt our ability to offer custom pricing to enterprises.

We don’t want to waste the sales team’s efforts on dealing with prospects whose potential deployment size is too small to pay for the sales and support efforts they would require.

We don’t want to let bad actors use the product for malicious purposes.

We don’t want our product teams to lose focus on what matters.

We don’t want to lose potential business opportunities or mislead ourselves into assuming that there will be big deals coming out of the self-serve user group if there are no signs of that happening.

Now that we agree on these goals, let’s see what thinking about PLG from first principles could look like.

Start by developing an understanding if people in your target group would even care about having the ability to get started with the tool in a self-serve manner. My observation is that security practitioners with an engineering mindset (security engineers, detection engineers, security architects, automation engineers, etc.) and people who have home labs are much more likely to care about the ability to get started with the tool than others. It doesn’t help to have a free signup for, say, a GRC tool if people working in GRC don’t care about trying products on their own (I am not sure if they do, but using it as an example). If people in your target group don't actively try, experiment, and tinker with different tools in their spare time, you are less likely to succeed with PLG efforts.

Then, assess if your product is at the point when it can be made self-serve. If the company is very early and is still in the process of refining the problem, iterating on the solution, and looking for product-market fit, having conversations with as many customers as possible is more important than streamlining signups. In these circumstances, I would 100% require a mandatory demo before letting people get started; not to sell but to make sure I understand their needs. A free trial or a free tier with a mandatory demo could be an option. If the product is too early, too complex, or needs access to too much sensitive data, I would also keep the demo required and not have a self-serve signup. Without proper guidance and a degree of trust to get started, churn is much more likely.

Before going any further, I would have a very critical look if the product is suitable for self-serve. Can a user understand the value the system offers, quickly? With a VPN, I know in two minutes if it works as intended. With a security automation tool, I should be able to quickly start with a demo flow and see how that would work in my environment. With a platform that provides access to content (detections, threat intelligence, etc.), I should be able to see the value of that quickly as well. On the other hand, with a tool like User Entity and Behavior Analytics (UEBA), can I understand what it does and see the value quickly? If the answer is “No”, then it is probably not a good fit. It is worth reminding that a dashboard is not the same as value; value is when the user sees how their problem is being or can be solved. With 1Password, Bitwarden, or any other password manager, I can save my password immediately - now that’s an immediate value. Waiting for six weeks to see if a tool will detect something, and looking at the dashboard in anticipation that will happen, is not.

In those rare cases when you did identify that PLG could be a way to go and that it is not likely to lead to high levels of churn, you can continue on that journey.

You will need to find a good way to bridge the self-serve experience with your traditional sales outreach. To start, you need a strong sales team. The role of sales only increases if you have a self-serve path. The majority of your customers (think 80-99%) will probably not come from free product signups: you need to continue generating demand, looking for leads, and closing sales deals. On top of that, you have to design a way to engage your free users, understand if they have a buying intent, and if they do (i.e. if they aren’t students looking to get hands-on experience with a security tool for free), you need to help them to get your product adopted across their organization.

To avoid wasting the precious sales team’s time on dealing with prospects whose potential deployment size is too small to pay for the sales and support efforts they would require, you may want to consider offering some kind of guided self-serve version for small organizations. Guiding SMBs to a self-serve path is a double-edged sword: they are often too small to justify human-assisted onboarding but require a lot of education before they can get started. Most enterprise-focused products don’t need to worry about SMBs as much because they are not looking for detection engineering platforms, data lakes, and all the other security tooling built for Fortune 1000 and mid-market enterprises.

When it comes to listing enterprise pricing publicly on the website, I would strongly warn against doing that. Having enterprise pricing public can hurt your ability to sell through the channel (unless you can offer a very deep discount for the channel to get the margin it needs), negotiate deals with enterprises (unless again, you can offer a very deep discount), or tailor pricing to address the unique needs of your customers.

To not lose the ability of your product teams to focus on what matters, and to avoid misleading yourself into thinking that the self-serve mode is going to be a game changer, you will need to have the ability to segment your free tier users. In ways that are not invasive, try to collect some information to understand who they are, what they are looking to do, and what the product must provide to satisfy their needs.

If there is the chance that your solution can be used by bad actors, make sure to scope your free tier (or free trial) in such a way that reduces the probability of that happening as much as possible. This is especially relevant if your tool can be weaponized and used to cause harm to others.

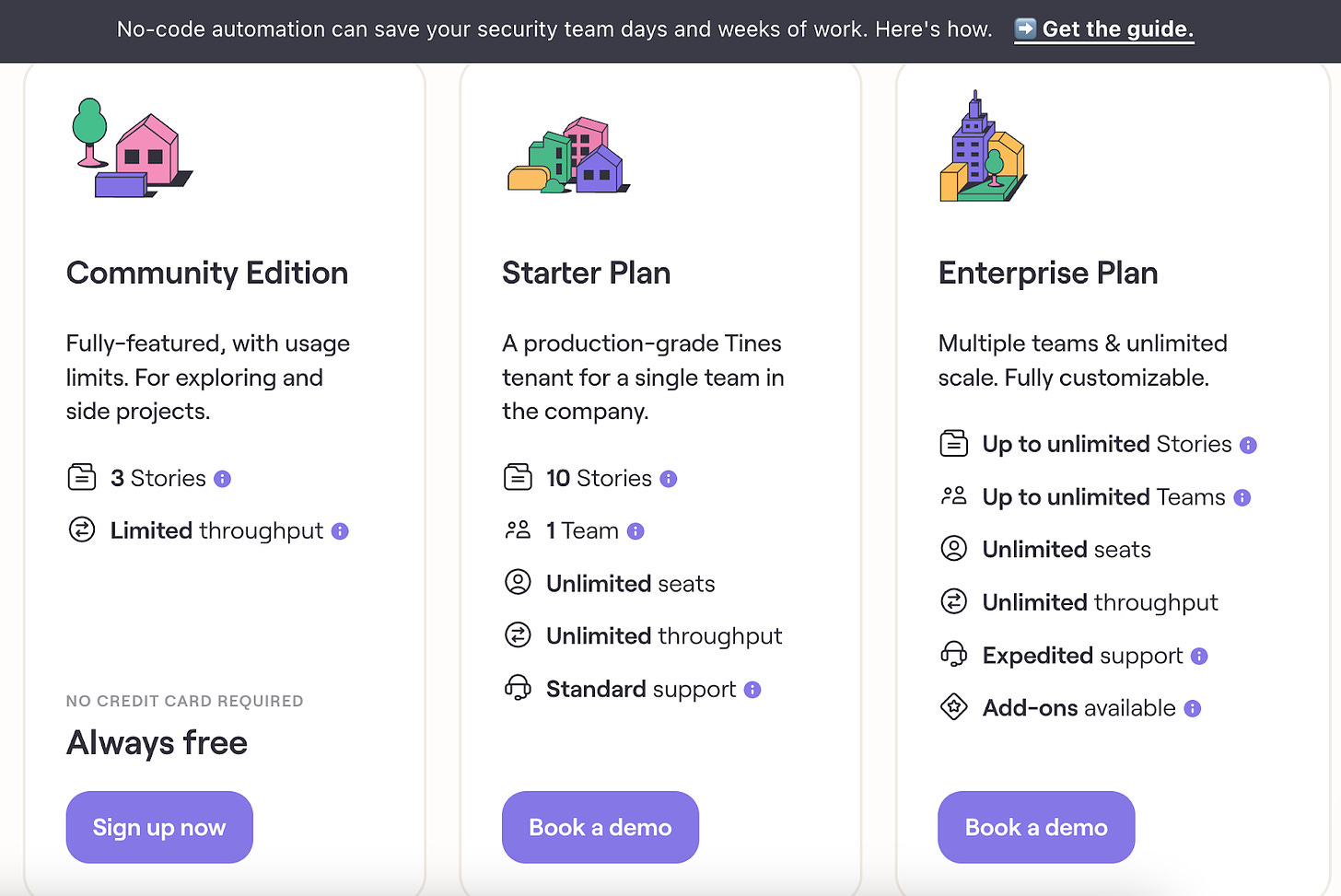

Here is an excerpt from my other article about PLG that remains incredibly relevant until today. “Product-led growth is not a boolean, it is a scale. We are used to thinking that a company is either "PLG" or "not PLG", but in real life, it is rarely that simple. Product-led growth takes all shapes. A great example of a product that treads the line between PLG and a sales-led approach is Tines. Tines offers users the ability to try the product, test it in their home lab or their company at a small scale, and experience the value in a self-serve manner without having to worry about pricing and contracts. Keeping their basic pricing tier free creates a great opportunity to serve practitioners, build a community around the product, and get hands-on security professionals to try, test, and learn how to use the tool. On the other hand, companies interested in adopting the solution are expected to go through the sales process. The absence of publicly listed pricing keeps the room open to sales via channel as well as reseller arrangements.

This isn’t an example of how PLG “should be” done as there are no recipes for success. Snyk, for example, takes a different path and offers a fully self-serve experience with transparent pricing anyone can access by creating an account on their site.” - Source: PLG is not a boolean: practical advice for cybersecurity startups looking to embrace product-led growth

Closing thoughts

Having covered so much ground and so many reasons why cybersecurity startups should not be getting overly excited about PLG, I still think that product-led growth in security is a good idea. Implementing elements of product-led growth that make sense for a particular company can be a great way to supercharge growth, supplement the traditional go-to-market motion with an additional way of generating revenue, build trust with security practitioners who are future leaders, and grow market share.

Starting from first principles is and has always been the key part: no type of go-to-market motion, no matter how much it is overhyped, is going to be a magical solution to all problems. Founders and startup leaders must seek to understand their problem space and the customer needs of their market segment, and be willing to test and experiment to learn what ways of capturing value could be best suited for their specific situation.

You can learn more about building security startups and designing go-to-market strategies in my book, “Cyber for Builders: The Essential Guide to Building a Cybersecurity Startup”.

Great read, interesting perspective.

I tend to think that the "shift-left" trend works well with PLG.

For example, in the world of secret management, Hashicorp's strategy was to offer vault for free (open source), drive adoption by development teams and then once an organisation has adopted vault they would contact the security team and offer them to improve their governance by signing an enterprise contract.

It seems the challengers in this category are also using PLG: https://www.doppler.com/ & https://aembit.io/

Excellent read. Ross! As is your book! Shameless plug to my own substack

https://marketingmicrodose.substack.com/p/the-marketing-microdose-a-little-63f