5 skills and potential career paths for cybersecurity of the future

In this article, I am discussing five skills and potential career paths for cybersecurity in the future

What will the future of cybersecurity look like? The truth is, no matter what we say, nobody has an answer to that question. Some of the so-called “predictions” are purely self-serving, others are overly optimistic (or pessimistic depending on what you read), even if devoid of any hidden agenda. I don’t have any more answers about that future than anybody else, but I think there are critical gaps that simply need to be addressed in one form or another. Several of these gaps require skills that are not readily available today.

In this article, I am discussing five skills and potential career paths for cybersecurity in the future. This is not an attempt to predict the future, but a discussion about what is missing, how these gaps could be addressed, what skills will be needed to address them, and what people can do to obtain these skills.

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Over 3,500 copies of my best selling book “Cyber for Builders: The Essential Guide to Building a Cybersecurity Startup” have been distributed to the readers so far.

The book is intended first and foremost for builders - startup founders, security engineers, marketing and sales teams, product managers, VCs, angel investors, software developers, investor relations and analyst relations professionals, and others who are building the future of cybersecurity. If this sounds like you, you should get a copy. The book has been rated 4.9 out of 5 on Amazon based on 80+ reviews, and in 2024 it became a finalist of the SANS Cybersecurity Difference Makers Awards.

5 skills and potential career paths for cybersecurity of the future

Cyberpsychology or psychology of security behavior

One of the most critical aspects of cybersecurity is finding ways in which it can be seamlessly integrated into the way people live and work, without impacting their productivity, ability to do their jobs effectively, and requiring them to change their way of working. I find it fascinating that decades later, the industry still believes that writing tens or even hundreds of pages-long policies and forcing people to “comply” with these policies is the right way to go about building a culture of security. All this is while areas of knowledge such as decision science and behavioral psychology have taught us that to achieve lasting behavioral change, we need to understand how people’s minds work and leverage that understanding to come up with systems and processes they are likely to embrace.

For us to evolve as an industry, we need to change the way we think about security. In practical terms, this means that:

Schools that train the next generation of security practitioners should teach a course in cyberpsychology or the psychology of security behavior. Security certification providers should be doing the same, recognizing that technology skills alone are not enough to secure organizations.

Security leaders and practitioners should seek to upskill themselves on the topics of behavioral psychology. The work of Daniel Kahneman, Robert Cialdini, Dan Ariely, and Daniel H. Pink, to name a few, should be on their reading list. Concepts such as anchoring, halo effect, bandwagon effect, confirmation bias, and many others should be understood by everyone working in security.

We need more researchers in academia focused on studying the topic of cyberpsychology and learning about the ways we as an industry can improve security habits.

Historically, security would add friction and processes that made things harder for regular people. This, in turn, encouraged people to seek workarounds so that they can do their jobs more effectively. Armed with an understanding of how humans operate, we must evolve the industry and make security frictionless.

The good news is that we are making good progress. People like Jason Chan have been championing the idea of guardrails and paved roads - or building secure default for software engineers. If a secure way of accomplishing a task is going to require substantially less friction than an insecure way, this alone will do more to promote secure behaviors than any training can.

Here are some resources for those interested in cyberpsychology:

Work of Prof. Mary Aiken, including her book “The Cyber Effect: An Expert in Cyberpsychology Explains How Technology Is Shaping Our Children, Our Behavior, and Our Values--and What We Can Do About It”

“Payoff: The Hidden Logic That Shapes Our Motivations” by Dan Ariely

“Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us” by Daniel H. Pink

“The Optimism Bias: A Tour of the Irrationally Positive Brain” by Tali Sharot

Cybersecurity user experience

While having a deep understanding of human psychology and behavior is critical, it is not enough. We must find a way to use that understanding to shape how cybersecurity solutions work and how they fit into people’s day-to-day lives.

There are several dimensions:

For end users, security should be invisible. As much as possible we should be looking for ways to abstract away the complexity of security from people’s daily lives. Instead of training them on how to avoid making mistakes, we should seek to provide pre-built tools (libraries, configurations, etc.) that are secure by design. Security practitioners are guilty of neglecting user experience, and a broader conversation is needed for us to move past this. We continue to believe that we can enforce security with policies, while what we should be doing instead is building it with good UX.

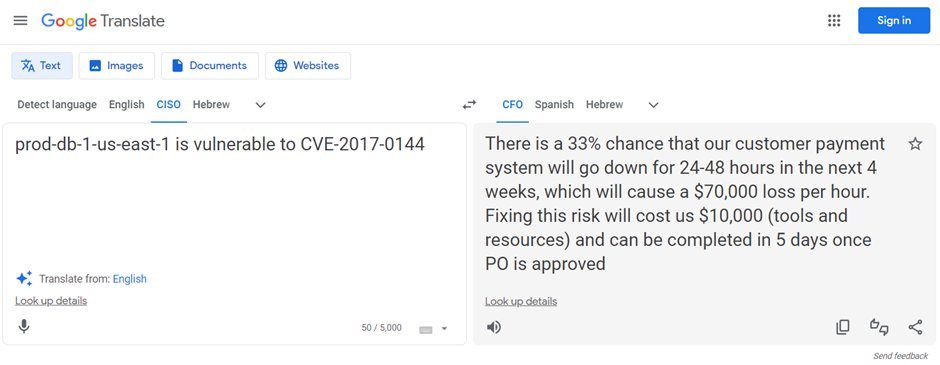

For business leaders, security should be easy to understand. I would argue that our inability to communicate security problems in ways people can understand is both a communication and a user experience problem. Security leaders are guilty of neglecting user experience, and a broader conversation is needed for us to move past this.

Source: Elad Erez

For security practitioners, security should be easy to configure and maintain. By their very nature, security tools must go incredibly deep, and deep usually means complex. For decades, buyers of security solutions were forced to read thick books of user manuals and seek help from professional consultants just to implement the tools they bought. Over time, as vendors introduce more and more new capabilities, customers’ implementation would rapidly regress since nobody has the time to go through 50+ tools manually and explore what’s new in their UI. Security vendors are guilty of neglecting user experience, and once again, a broader conversation is needed for us to move past this.

On the vendor side, user experience has for the longest time been an afterthought despite the fact that there are plenty of examples that show that cybersecurity is very much about a great UX. For example,

Duo Security built a multi-billion-dollar business by removing friction from MFA implementation.

Thinkst Canary bootstrapped to about $20M ARR by sweating over UX and making it easy to deploy its solutions.

Wiz became an industry leader in cloud security, to a large degree because of its UX and quick time to value.

The security startups are slowly realizing that it’s not just consumer products that should care about good user experience, but also B2B solutions. There is a lot of money in good UX.

On the practitioner side, the realization that user experience is key is much slower but I am convinced it is inevitable. There is a lot of room for improvement. For once, I think we are lacking skills in user discovery. Most security practitioners assume that their own way of seeing the world is the right way, and instead of trying to learn how others do their work and what their needs are, they focus on building what they think is needed. That, too, is going to continue evolving. As one person commented on my LinkedIn post, “It’s time to transition “security awareness” into “security behavior & user experience”. I could not have said it better.

Here are some resources for people interested in cybersecurity user experience:

UX Daily: The World’s Largest Free Online Resource on UX Design

“Customer love: a recipe for building winning cybersecurity startups” from Venture in Security

Cybersecurity product management

I like to quote Gibson Biddle, former VP of Product at Netflix, who says that the job of product managers is to delight customers in hard-to-copy, margin-enhancing ways. In other words, it’s about taking into consideration hundreds of inputs, deciding what needs to be done, prioritizing what’s essential against everything else that also looks essential, and making things happen while managing stakeholder expectations and keeping everyone aligned.

The role of product managers in today’s technology world is hard to overestimate. Behind every successful technology product is a team led by a product leader (while their titles may vary, the nature of the role is similar across most organizations). I have observed that cybersecurity is yet to fully realize the importance of product management, both for security teams and for security vendors.

Over two years ago, I wrote a piece titled “Why security teams should start recruiting product managers” which in my view aged incredibly well. I argued that “We need people who will bridge the increasingly complex technical side of cybersecurity with the problems, habits, and needs of people who are affecting and will be affected by security. We need people who understand the business goals, objectives, as well as cybersecurity to prioritize the work technical teams are doing and to focus on what truly matters. We need people who would not use jargon or abbreviations when talking to the users, people who would talk in terms of simple-to-understand use cases, and who would be asking powerful questions instead of talking. We need security professionals armed with empathy and curiosity, not policies and procedures. We need people who will become experts in continuous discovery, a security-focused version of Teresa Torres’ work. We need people in security who see their work as being partners, not judges, people who can act like business enablers, not business warriors. In software development, product managers are the ones who act as translators between business and technology. I don’t know what they will be called in cybersecurity — Security Champions, Security Owners, or whatever else will fit the bill. We need someone.” We need people who are focused on seeing the big picture, identifying the right stakeholders, getting them to work together, and aligning technology with business. This was true before and it remains to be true today. We are starting to see how this idea is becoming a reality since the role of BISO - Business Information Security Officer - closely resembles that of a PM.

Not only will security teams benefit from having a PM on the team, but I think we will also start seeing more security vendors hiring professional product leaders. There is an acute shortage of product managers in security who both understand security and have experience working in other industries. The reason why we don’t have enough solid product people on the vendor side is simple: most startups get acquired very early, well before they can build a robust product function, and most large companies are too slow-moving to be hotbeds for innovation. Fast-growing successful companies such as Vanta, Data, Wiz, Abnormal, and the like are where the future of product management will likely come from.

Here are some resources for people interested in cybersecurity product management:

“Why security teams should start recruiting product managers” from Venture in Security

“Inspired: How to Create Tech Products Customers Love” by Marty Cagan

Cybersecurity intelligence

I think one of the hottest future jobs in security is going to be at the intersection of cybersecurity and data science/machine learning/artificial intelligence. So much of security is a problem of analyzing large amounts of data, and so few security practitioners have the skills to work with data. While security analysts, security engineers, and detection engineers, to name some, can most definitely search data using security tools, relatively few of them can perform analysis of the data at scale.

On the other hand, people who are good with data usually don’t understand cybersecurity. Data scientists may be great at extracting insights from large datasets, but they have little understanding of the security implications of those insights. In order for them to effectively translate data patterns into meaningful security intelligence, they will need to learn the fundamentals of cybersecurity.

Whether or not AI is going to magically solve all problems, it is clear that security will continue to make use of data science, machine learning, and artificial intelligence. In a world where the importance of security is increasing, and a lot of what we know as security is becoming a data problem, people who possess expertise at the intersection of these areas will be generously rewarded.

Here are some resources for people interested in cybersecurity intelligence:

“Why AI and machine learning are cybersecurity problems — and solutions” by EY

Plenty of courses from both traditional institutions and online education providers

Cybersecurity economics

When we talk about the importance of cybersecurity, it often sounds like the reasons it’s important have more to do with “doing the right thing” than achieving a specific goal. The reality is that security exists in the broader economic context, and as such it has to be able to communicate its economic value.

At the very fundamental level, economics is the study of choice that analyzes and optimizes the allocation of scarce resources in ways that maximize return on investment. In my view, nothing is as good at providing theoretical foundations for making decisions in uncertainty as the field of economics. Cyber insurance, in particular, is going to have an increased impact on the future of security, since it is the only area adjacent to security where the incentives are aligned perfectly well: insurance companies are very interested in reducing the number of breaches since that reduces the amount of claims they have to pay.

I can't picture the future of cybersecurity without people who can make sense of the economics of security. High-pressure, high-performance decision-making, game theory, statistics, and other economic aspects will inform how the industry develops, and therefore we will need people who can articulate security problems from economic lenses.

Here are some resources for people interested in cybersecurity economics:

The future doesn’t come, it is built

I think the number one reason most predictions about the future turn out to be wrong is because people who make them assume that the future is going to be based on some kind of trend, and sometimes even an inevitability. The truth is that the future doesn’t come; it is built. For security tomorrow to look different than security today, we need people who advocate for new ways, and we need people who lead these new ways.

In this article, I wanted to describe what I believe are the skills cybersecurity of the future will need. Will each of these skills correspond to a career? Time will tell. Even if they will, it doesn’t mean that there will be plenty of jobs in these areas. Case in point are security engineering (it is here but not evenly distributed) and privacy engineering (the Master’s program at Carnegie Mellon is preparing people for jobs at Google, Meta, and a few other companies since there has not been a wide adoption of this role).

What’s clear to me is that security has no choice but to leverage the body of knowledge from other disciplines such as decision science, behavioral psychology, user-centered design, product management, economics, software engineering, and data science, to name a few. And, if we fail to do that, we will continue trying to reinvent the wheel and spin in circles solving problems other industries have solved decades ago. I surely hope that is not going to happen.

Hey Ross,

What a fantastic article! As a recent graduate in cybersecurity engineering, I have a solid foundation in the topics you've covered. I truly believe that mastering these skills is essential for establishing a robust security posture. Thank you for sharing your valuable insights with all of us, it’s much appreciated!

Best regards,

Saad M