Trust no one: why we can't trust most stats about the cybersecurity industry, and why we must stop creating numbers out of thin air

In this piece, I am discussing why it is so hard to find reliable sources of information about security, why we should not be creating data out of thin air, and where we should go from here

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

If you didn’t get a copy of my best selling book “Cyber for Builders: The Essential Guide to Building a Cybersecurity Startup” yet, now is the time to do it. This book is unique as it talks about building cybersecurity startups. It is intended for current and aspiring cybersecurity startup founders, security practitioners, marketing and sales teams, product managers, investors, software developers, industry analysts, and others who are building the future of cybersecurity or interested in learning how to do it.

There is a problem in cybersecurity: solid industry analysis is hard to come by. I am not talking about the articles about the ever-emerging categories and new abbreviations. Instead, I am talking about higher-level stats about security as an industry and security as a practice. In this piece, I am discussing why it is so hard to find reliable sources of information about security, why we should not be creating data out of thin air, and where we should go from here.

Looking at security as an industry

When I think about security as an industry, I think about questions such as:

How many jobs are open in security?

What are the types of jobs that remain unfilled? Why is that the case?

What does the security industry look like in the US? What does it look like outside of the US, in, say, countries of Africa or Australia?

What is the aggregate amount of losses caused by cybercrime, in the US and globally?

What kinds of organizations are impacted the most?

How many companies go out of business after security breaches?

Although one would assume that answers to these questions should be relatively easy to find, that could not be further from the truth. The difference between the numbers casually thrown around is mind-boggling. For example, while Statista estimates the 2023 cybercrime costs in the United States to be around $320 billion, according to Cybersecurity Ventures, cybercrime in 2023 was predicted to cost the world $8 trillion, or 25 times Statista’s US cost. Sure, one is a global number and another is US-focused, but I would expect to see the US share of cybercrime to be more than 4% of the global figures, given that the US market is likely being targeted the most. Or, take the so-called cybersecurity talent shortage problem. Within 2023 alone, the estimates for what that shortage looks like went from 3.4 million people in January to 4 million in October. It is unclear what kind of changes in the field have created a demand for another half a million people, especially given the state of the economy, mostly frozen security budgets, and the evidence on social media that quite a few people seem to be looking for entry-level jobs.

To unravel what is happening with these and many other stats and whether they can be trusted at all, it is worth discussing the parties behind the data, incentives that drive them, processes they have in place to ensure the validity of the data, and how that impacts the credibility of what they produce.

Industry analyst firms

Industry analyst firms are organizations that employ analysts whose role is to know the industry, its products, people, and trends. Industry analysts are not like your traditional cybersecurity analyst: rather than having significant technical domain expertise, they are usually (but not always) individuals with years of broader experience in enterprise environments who have a mixture of knowledge covering technology, business, and more.

Analysts add value to the cybersecurity ecosystem by:

Publishing research about market trends, technologies, and forces shaping the future of the industry.

Conducting vendor briefings - talking to different companies on the market, learning about their products and services, and distilling their learnings into easy-to-understand summaries.

Answering vendors’ questions about the market, product, and the go-to-market strategy.

Advising enterprise business and security leaders about vendors, products, and the most effective ways to tackle problems they are facing.

Organizing events and webinars, speaking at industry conferences, and engaging in other forms of thought leadership.

I have previously written about industry analysts in my blog and my book “Cyber for Builders” in depth.

Industry analyst firms play a unique role in the market by simultaneously selling subscriptions to their services to two groups of customers: security vendors and buyers. That said, most advisory firms sell primarily, and some - exclusively to security vendors.

Many people assume that industry analysts are biased and “pay to play”, which refers to the practice of altering research results - vendor rankings, opinions, and reports - influenced by commercial relationships. The reality is much more complex.

All the analysts I know are objective and unbiased people who are deeply knowledgeable and passionate about the future of security. More so, despite the never-ending rumors of the “pay to play”, I have not come across any documented evidence of that happening in the top-tier firms. Large companies have strict rules about conflict of interest and would terminate any analyst who does not disclose such a conflict. The same, however, cannot always be said about a select few small firms that write “whitepapers” and “research” paid for and approved by vendors that are then used for lead generation.

Two factors lead to the perceived subjectivity of industry analyst firms:

Industry analysts operate in a system that by design, creates a huge potential for conflict of interest. Analyst firms take money from two sides with diametrically opposite interests: sellers who pay with the intent to generate demand for their products, and buyers paying for objective advice.

Industry analysts have limited information about the vendors they evaluate. When analysts write reviews of security tools, they normally do it based on product demos and discussions with company customers who agree to provide references for the vendor. In the case of emerging vendors and markets, the ratio of vendors to customers might be as high as 5:1. The perspective analysts develop without being hands-on, and testing the tool in an appropriate environment, can be of limited value to customers and industry insiders. Even if analysts were formerly hands-on technical professionals, this knowledge ages out quickly.

It is worth emphasizing that top-tier analyst firms are using rigorous tools in their research practices, and while industry analysts are not academics, they end up producing high-quality, well-argued outputs. However, industry analyst firms are not research institutions designed to understand the future of cybersecurity and the dynamics in the field. Instead, they exist to answer questions of their paid customers (large enterprises and large security vendors), and the direction of these questions naturally gets to define where analysts will spend their time, which is usually on looking at market segments and products. Research produced by top-tier analyst firms is useful for understanding the security needs and the trends surrounding large enterprises. It is, however, usually of limited use for understanding the industry as a whole, beyond Fortune 1000, the US market, and specific product categories. Even then, given the incentive systems at play, it is not surprising that many in the industry are not too excited about reading analyst reports, and most people in the industry will never be able to access them.

Training and certification providers

Training and certification providers have emerged as a strong voice of cybersecurity industry insights. The International Information System Security Certification Consortium, or ISC2, a non-profit organization that specializes in training and certifications for cybersecurity professionals, has been arguably one of the most active players. ISC2 has attracted over 500,000 members, which makes some in the industry refer to it as the "world's largest IT security organization".

Having grown into a powerhouse of cybersecurity talent, ISC2 became one of the world’s largest producers of industry insights, member surveys, and reports about important trends in the field. Intuitively, this makes sense: any organization that has the ability to reach out to half a million people and ask them to answer a set of questions can become a strong voice in its domain. That is exactly what happened, and for the past number of years, ISC2 has been conducting an annual Cyber Workforce Study. In October 2023, a record 14,865 cybersecurity professionals shared their unique perspectives on the state of the workforce.

That brings us to the most interesting question of this story: the incentives. As a training provider, ISC2 has all the incentives to see more people register for certifications and go through its courses. This is one of the reasons why it is so suspicious that the numbers behind the so-called cybersecurity talent shortage come precisely from the surveys of ISC2. The ISC2 Cyber Workplace Studies are the main source for the industry-wide panic of needing to hire 4 million cybersecurity practitioners. The ISC2 studies have been quoted by the World Economic Forum, NIST, SC Media, Cybersecurity Dive, Dark Reading, Forbes, ComputerWeekly, IBM, Accenture, Fortinet, and many others.

Ben Rothke recently published a great piece about the ISC2 and its talent shortage estimates titled “The big lie of millions of information security jobs”. In the article, Ben writes, “A problem with the ISC2 Cyber Workforce Study is that the main data source is the survey. And a survey alone, even combined with secondary data sources, is not enough to get good actionable data. Also, 47% of the respondents were non-managerial mid or advanced-level staff, entry/junior-level staff or independent contractor/consultant. They may not have their pulse on hiring, or even have hiring responsibilities. 50% of those surveyed replied ‘I interview candidates and influence decisions but do not make final decisions’ and ‘I do not have hiring authority or influence over decisions about hiring’. And only 40% were from the USA”.

I think the issue here is twofold. First, a training provider has every incentive to create demand for its products, and evangelizing about the need to have more people study and get certified to become security practitioners is a great way to do it. Second, it is highly questionable how one can extrapolate the global demand for security professionals based on responses of ~15,000 security practitioners at different stages of their careers. Either way, the insights produced by ISC2 and similar organizations, while useful, have to be treated with some analysis and a healthy dose of skepticism.

Independent analysts and blogs

There are many great cybersecurity blogs and a handful of independent analysts who have been seen as authorities in the space. To avoid accidentally sounding overly critical of any of them, I will be discussing Venture in Security.

Venture in Security is my personal blog, and I try very hard to keep it an unbiased source of insights. That said, there are a few challenges. First and foremost, this is my weekend project, and although I spend anywhere between five and twenty-five hours on one post, I do not have the time to make it fully objective. To my credit, I try hard to list my opinions as opinions, not facts, and draw the line between something I have validated with a sufficient dataset (such as analyzing 824 vendors or looking at Fortune 500 CISO profiles) and something I haven’t. Whatever I am doing, my goal is to offer a perspective - a perspective rooted in my experience and analysis, a perspective that is subjective, and a perspective that may or may not be relevant to everyone in the industry.

The same can be said about other independent bloggers in the space - Clint Gibler, Mike Privette, Chris Hughes, Phil Venables, Cole Grolmus, Tyler Shields, Frank Wang, Walter Haydock, Darwin Salazar, and many others. We all have opinions and perspectives, but none of us allocates many weeks of full-time work to perfect a single analytical piece and validate every source, nor do most of us see that as our goal.

When reading independent blogs, it is important to keep in mind the incentives of their authors and be mindful of how these incentives can impact the direction of their thinking, and the perspectives they are sharing, either directly or indirectly. Your mileage may vary here. As for myself, I keep Venture in Security as a way to share my learnings, perspectives, and opinions about the industry, as well as my experience building products and investing in security startups. Some other people may see writing as a lead generation channel for their companies, a way to make money, or something entirely different.

What I also try to keep in mind is the non-intentional bias of people’s networks. Venture in Security attracts ambitious founders, innovative security leaders, practitioners building their products or experimenting with different ideas on the side, and value-focused investors, to name some. Naturally, if, in one of my pieces, I were to offer a perspective of, say, security practitioners, I would be featuring someone passionate about what they are doing, and not someone who doesn’t care about their craft. We all create our own echo chambers, and depending on who we surround ourselves with, our take on the same problems can be dramatically different.

Because our networks tend to amplify our thoughts, whenever authors of personal blogs conduct surveys of their audience, they have to be mindful to not present them as an objective perspective from the industry. The demographics of the responders matter. It makes sense, for example, that readers of a blog about security automation would think that it’s important for every company to automate its security operations. This insight has to be thought of critically because it doesn’t mean that people in the broader industry share the same sentiment.

Lastly, many independent blogs accept sponsorship from security vendors. While some do it in a way that does not impact the objectivity of the content, the lines can often blur. If a vendor is sponsoring an analytical post about its own product category, one has the right to question the objectivity of such analysis.

Data aggregators

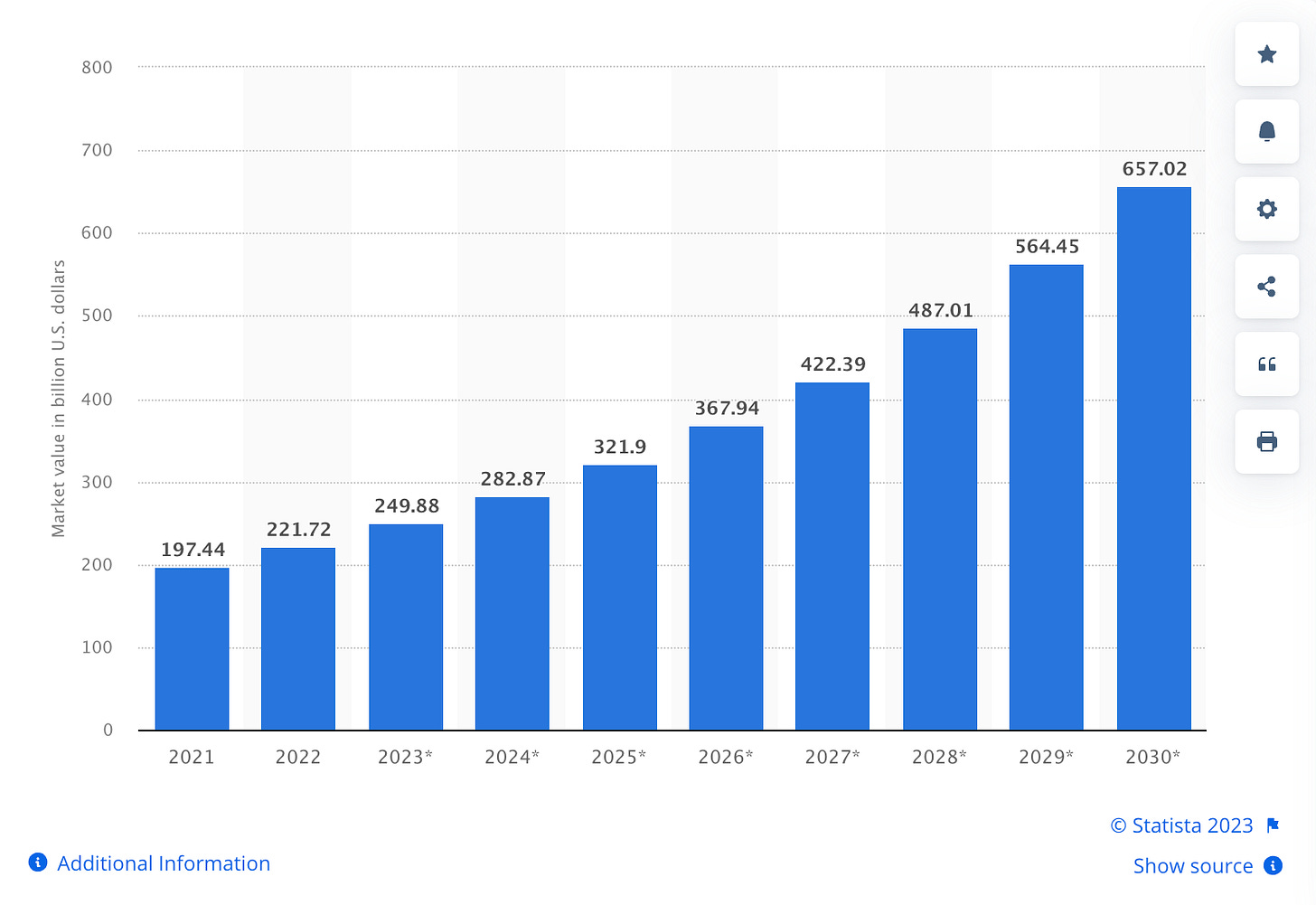

Data aggregators such as Statista are commonly cited when people are looking for numbers to back their claims. I did it several times myself when there were no other sources. Sadly, data aggregators are not a reliable source of analytics. Their infotainment graphs are reported to contain a large number of errors and often contradict one another. Moreover, they are not sourcing data themselves - in most cases, they present data from other sources, many of which are publicly available. The issue is that when people google questions about the security market size or cybercrime loss amounts, to name a few, these charts often show up on the first page.

To summarize, charts from Statista and similar vendors are not reliable sources of data. They may look attractive, but they lack rigor and are typically based on straight-line projections that assume that the future will look exactly like the past, an assumption that has been disproven again and again.

Source: Size of cyber security market worldwide from 2021 to 2030

Media companies

Media companies that cover security can be categorized into three groups: cybersecurity-focused media such as Dark Reading and Security Week, tech media such as TechCrunch and VentureBeat, and broad media such as Forbes and The Wall Street Journal.

Some cybersecurity- and technology-focused media such as BleepingComputer and Wired often hire journalists with technical backgrounds and even a degree in computer science. Others avoid doing it, and usually by design: cybersecurity domain knowledge can hinder the journalist’s ability to identify what the real story is and understand what level of details would be interesting to an average reader. Whether or not journalists are domain experts, when reporting cybersecurity news, they need to be careful and critical of what they are hearing.

If and when the journalists lose their guard and go for the simplest and the most sensationalist explanation of the problem, bad things happen. In 2023, the news appeared that a military AI drone killed an operator. The news spread like wildfire only to later be debunked as a misunderstanding: according to the update to this story, it was just a hypothetical idea. "We've never run that experiment, nor would we need to in order to realize that this is a plausible outcome." Several weeks ago, another news story spread on social media with sensationalist headlines such as “Beware, your electric toothbrush may have been hacked”. This time it was about the “fact” that 3 million electric toothbrushes were used in a DDoS attack. A few days later, after pushback from many security practitioners, we learned that it was a hypothetical scenario instead of an actual attack. Following this event, Graham Cluley wrote a great piece about how misinformation spreads in the cybersecurity world. Earlier this year, we also learned that “JPMorgan battles 45 billion daily hacking attempts with $15 billion defense arsenal amid rising cyber threats”. Obviously, the 45 billion figure isn’t quite true, but most people will never know that, and most journalists didn’t question the numbers provided by the JPMorgan executive.

The list of these misunderstandings can go on and on. The vast majority of mistakes are genuine, unintentional, and seemingly harmless omissions. However, we must be careful the next time we hear about a new cybersecurity attack: it is likely to be a hoax. Worse yet, we can get numb to these headlines and stop paying attention to security right around the time when we should be looking to become more vigilant about our digital safety habits.

Not all media companies embrace the same high-integrity approach to their work, and since their business models and ways in which they make money vary, so do their beliefs about what is acceptable in their field. The business model of media companies working in the B2B space often requires them to take sponsorship from vendors, which has a high potential of impacting the angle of their coverage. Additionally, the very nature of the media business model incentivizes them to see their content go “viral”, which sometimes leads to clickbait, sensationalist statements, and spreading fear, uncertainty, and doubt (FUD) in the industry. That said, most of the time mistakes are genuine, and as long as a media company recognizes the boundaries it operates within, and makes it clear to its audience where these boundaries are, it will rarely run into any problems.

While some media companies focus on independent reporting, others take a more opinionated stance and position themselves similarly to analyst firms. One example is Cybersecurity Ventures, a media firm that has been playing an outsized role in the cybersecurity industry, and therefore deserves a separate call-out.

Cybersecurity Ventures describes itself as “the world’s leading researcher and Page ONE for the global cyber economy, and a trusted source for cybersecurity facts, figures, and statistics”. The word “researcher” is a key here as that’s exactly what Cybersecurity Ventures is known for. As the company proudly states on its website, “According to Cybersecurity Ventures” is one of the most popular phrases in the cybersecurity community”. Cybersecurity Ventures has indeed been the main source behind many (and I would even dare to say, most) of the boldest and most frequently shared stats and predictions about the security industry. Cybersecurity Ventures’ prediction that “cybercrime will cost the world $8 trillion in 2023” has made it to Forbes and a wide variety of other media while its updated figure for 2025, $10.5 trillion, was quoted by McKinsey. Cybersecurity Ventures’ prediction that “the world will have 3.5 million unfilled cybersecurity jobs In 2023” has made it to CNBC and other media. Then, there are predictions about crypto crime, cyber insurance, the number of internet users, and more:

“Cybersecurity Ventures predicted that a business fell victim to a ransomware attack every 11 seconds in 2021, up from every 14 seconds in 2019. The frequency of ransomware attacks on governments, businesses, consumers, and devices will continue to rise over the next five years and is expected to rise to every two seconds by 2031” - Source: Cybersecurity Ventures

“Cybersecurity Ventures predicts that global spending on cybersecurity products and services will exceed $1.75 trillion USD cumulatively for the five-year period from 2021 to 2025, growing 15 percent year-over-year.” - Source: Cybersecurity Ventures

“Cybersecurity Ventures predicts the global security awareness training market will exceed $10 billion annually by 2027, up from around $5.6 billion in 2023, based on 15 percent year-over-year growth.” - Source: Cybersecurity Ventures

“Cybersecurity Ventures predicts the global healthcare cybersecurity market will grow by 15 percent year-over-year over the next five years, reaching $125 billion USD by 2025.” - Source: Cybersecurity Ventures

There may indeed be solid methodology behind these predictions; the challenge is that it does not appear to be easily accessible on the company website. Instead of finding publicly available information about the sources for the numbers, I keep running into circular references leading back to the same predictions from Cybersecurity Ventures. This is a problem because claims without a valid basis are hard to disprove. Take the estimated cost of cybercrime - $10.5 trillion, or its previous incarnation of $8 trillion. It is hard to imagine where these numbers might be coming from, or how Cybersecurity Ventures aggregated the data not easily accessible to the governments or international organizations.

Media outlets have all the incentives to share big and scary numbers ($10.5 trillion losses!), and vendors in the industry are quick to incorporate them into their marketing materials with backlinks to the original post. These predictions are quoted by governments, academia, industry analysts, professional associations, and security companies. Do the authors of these reports and predictions consider what other players in the ecosystem such as the government, security firms, insurance companies, and others are doing? Do they understand the nuances of the business models ransomware groups rely on? Do they rely on credible sources? Maybe they do, but that isn’t easily apparent to a reader (at the very least, it has not been convincing to me). Cybersecurity is not a static field, and without an understanding of the multitude of factors and how they all play together, any predictions are just numbers created out of thin air.

The problem isn't the media companies or any specific media company. The challenge is that the cybersecurity industry has set a very low standard of what can be considered research, and we are taking any numbers we see at face value. We want to be excited, we want to be angry, we want to sell more tools, and we are willing to take anything that will allow us to do that. For those interested in learning about myths and lies in infosec, and the extent to which various media have been spreading disinformation, I highly recommend this talk by Adrian Sanabria who has dedicated a lot of time to the topic: Myths and lies in infosec (USENIX Conference).

Other sources

There are other sources of insights about the business side of the cybersecurity industry, including:

Venture firms - VCs frequently create summaries and market maps that reflect their investment thesis. Depending on the angle and the VC firm, the depth and usefulness of these reports vary. It’s worth remembering that VC opinions shared publicly are intended to shape the present and the future of the industry much more than offer an unbiased source of insights.

Investment banks - Cybersecurity industry reports by Momentum Cyber and Houlihan Lokey offer a great perspective but are typically limited to financials, category growth, and movement of capital.

Think tanks - Several think tanks produce reports about the state of the cybersecurity market as well.

Looking at security as a practice

When I think about security as a practice, I think about questions such as:

Where should the security team be spending its time?

What are the most important problem areas that need to be covered?

What is the probability of a security incident if a specific control is missing?

Unfortunately, finding sources of unbiased data about the practice of cybersecurity is as hard as finding information about the business side of the industry.

Cybersecurity vendors

Cybersecurity vendors are the most powerful source of industry reports for security practitioners. Darwin Salazar, author of The Cybersecurity Pulse, put together an Intel Hub - a centralized repository for cybersecurity-related research reports, carefully curated from a diverse range of over 90 sources. While in isolation, each source is quite interesting to read, taken as a whole they do not paint a holistic picture of security needs.

There are several reasons why that is the case. First and foremost this has to do with incentives. Cybersecurity vendors are producing these reports to act as marketing, brand, and lead gen collateral, and therefore they always tell the story that suits the vendor narrative. It would be shocking if a security automation company, for example, sponsored a report saying that security automation is not important, or if a cloud security vendor did not suggest that the cloud is the most critical attack vector to secure. The second challenge is that many surveys involve users who are already within the reach of the vendor and therefore are more likely to be aligned with its view of the world. Lastly, even when cybersecurity companies try their best to make their reports as neutral as possible, the ways the questions are phrased, or the ways the results are aggregated are still going to be designed to benefit the vendor. This makes sense - after all, they are the ones paying for the reports, and they aren’t doing it as a charity but as a tool to grow their business.

All this makes it hard for security leaders and practitioners to take vendor-sponsored reports as an unbiased source of industry insights. Moreover, since most tend to focus on one problem area or attack vector (take the State of Cyber Assets Report 2022 by JupiterOne or the Cloud Security Threat Report 2023 by Wiz), they do not help look at the organization’s security posture holistically.

There are two exceptions: technical reports, and some (not all) reports commissioned by platform companies. Technical reports, such as Verizon’s Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR), reports from Mandiant (now a part of Google), or this great analysis of the vulnerability and threat landscape from the Qualys team, are some examples. These sources are well thought out and can be very useful for security teams. So are some of the reports commissioned by platform companies such as Palo Alto, Microsoft, and CrowdStrike, but their focus often ends at the boundary of their platform capabilities. Moreover, security practitioners should be able to discern marketing from useful data, which can often be quite hard to do.

Personal blogs and industry events

Personal blogs of security practitioners and talks at practitioner-focused industry events can be quite useful for learning about different ways a specific problem can be or has been solved by different organizations.

The challenge, similar to the previously discussed challenges of independent analysts and personal blogs, is the small sample size (sometimes, a sample size of one), and a subjective take informed by one’s own experience. This may or may not be a problem, but speakers, bloggers, and presenters need to be upfront about their context, and the amount of resources they have to deploy on security. What a cloud-native venture-backed late-stage startup can afford to invest in security may be quite different compared to the resources a small retail coffee chain is willing to allocate to the function. Knowing where different people stand makes it easier to filter their suggestions and perspectives.

Another challenge has to do with the fact that many companies do not allow their security practitioners to discuss details of their approaches, tooling implementation, and architectural decisions with outsiders. As a result, the ideas we hear when attending events tend to all come from the same segment of the market.

Government organizations

Over the past several years, governments around the world started to pay more attention to security. The United States can be seen as a perfect example of what becomes possible when people truly passionate about the field are given an opportunity to turn their vision into reality. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) deserves a special mention. The agency has become instrumental in facilitating the collaboration between public and private sectors, and establishing infrastructure for information sharing, which includes the following:

“Automated Indicator Sharing (AIS). AIS enables real-time exchange of machine-readable cyber threat indicators and defensive measures to protect AIS participants and reduce the prevalence of cyberattacks.

Coordinated Vulnerability Disclosure Process. CISA's CVD program coordinates the remediation and public disclosure of newly identified cybersecurity vulnerabilities in products and services with the affected vendor(s).

Enhanced Cybersecurity Services. Enhanced Cybersecurity Services (ECS) is a voluntary information sharing program that assists owners and operators of critical infrastructure in enhancing the protection of their systems from unauthorized access, exploitation, or data exfiltration.” - Source: CISA

CISA frequently issues cybersecurity alerts and advisories, and I anticipate the agency will continue to play an important role in helping security practitioners focus on what matters. That said, I am not aware of any industry-wide reports by the agency, so it’s hard to say if it intends to produce some in the future to help security practitioners focus on what matters.

A great source for security practitioners is the NIST Cybersecurity Framework - a set of guidelines for mitigating organizational cybersecurity risks, published by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The NIST Cybersecurity Framework helps businesses of all sizes better understand, manage, and reduce their cybersecurity risk and protect their networks and data. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) are two other examples of how governments can enforce what they see as best practices in cybersecurity and data privacy.

Cybersecurity frameworks and government standards offer a holistic approach to cybersecurity. While, as I have discussed before, a compliance-first approach to security comes with a long list of shortcomings, these frameworks, if used the right way, can act as a good starting source of information for security leaders and practitioners.

The challenge is that while there are small pockets of innovation (such as the above-mentioned CISA), the government as a whole has a fairly rudimentary understanding of security, and it is yet to become a major voice in helping companies build better cyber defenses.

Other sources

Professional associations - Professional associations frequently share research and surveys about the best practices and learnings of their members. Additionally, they create their own security standards and benchmarks. For example, Service Organization Control (SOC) Type 2, a trust-based cybersecurity framework and auditing standard focused on verifying that vendors and partners are securely handling client data, was developed by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA).

International organizations - One of the examples of the role international organizations play in cybersecurity is the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO 27001 and ISO 27002 certifications are considered the international standard for validating a cybersecurity program.

Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs) - ISACS collect, analyze, and disseminate actionable threat information to their members and provide members with tools to mitigate risks and enhance resiliency. Most of their insights, however, are not shared with non-members.

Educational programs - Educational institutions spread knowledge among students, even if their ability to remain relevant and up-to-date is reliant on their staff and can vary greatly.

We can't trust any stats about the cybersecurity industry

It is hard to find any stats about the cybersecurity industry that can be trusted, regardless if we are talking about the business or the practice of cybersecurity. The reason is simple: there are no parties sufficiently incentivized to produce such an analysis. For example,

Industry analysts firms rarely have the tools or the time to do it. Their focus is on the needs of whoever pays their bills, predominantly large vendors and security leaders at Fortune 1000 enterprises.

Training and certification providers are incentivized to create hype about the talent shortage and millions of unfilled cybersecurity jobs.

Independent analysts and bloggers are not rigorous enough and therefore paint a very subjective picture of the industry.

Data aggregators are focused on the creation of nice visuals and charts, not on checking the accuracy of the underlying data.

Security vendors invest in reports that are biased to paint them and their problem areas as most important and generate leads.

Organizations focused on compliance and frameworks tend to quickly get out of touch with real life because the threat landscape moves much faster than security frameworks.

Government organizations are too new to offer an actionable perspective, although I hope they will be playing an increasingly important role.

VCs have the incentives to focus on what either fits their investment thesis, what supports their portfolio companies, generates a pipeline of prospective founders, or opens the doors to certain types of deals.

Then, there is the fact that we simply don’t have the data that can be publicly accessed, analyzed, and aggregated. On an international level, we have established the infrastructure to share health data, but with cybersecurity being such a new discipline, that work has not yet happened. Some people rightfully suggest that we need to establish the NATO of cybersecurity, but I think we would do well by at the very least establishing a WHO-like organization for sharing the information first.

Before we get to the place where we can aggregate global datasets, we need to at least have the ability to see what’s happening within our borders. As of today, most of the root causes of security incidents never become public - they are protected under non-disclosure agreements and employment contracts of security leaders and practitioners. The new SEC rules will only apply to public companies, and that’s not the whole economy. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, publicly traded companies constitute less than 1 percent of all US firms and about one-third of US employment in the non-farm business sector (data as of 2007). Assuming that these numbers are still relevant today, we need to get visibility into the other 99% of the businesses employing two-thirds of the US population.

I am hopeful that this void can be filled by insurance companies. Insurance companies are the ones that know how much different businesses pay to cybercriminals in a given year, and therefore they are perfectly positioned to estimate the actual amount of security-related losses. Since insurance companies know or ought to know how each incident happened, they should also be in a good place to suggest where security teams should be concentrating their efforts to achieve the highest return on investment.

Government agencies such as the above-mentioned CISA, as well as ISACs, have their role to play as well. And, the industry needs researchers - people with a high degree of integrity who are economically aligned to not spread FUD but to look at things the way they are. How and where they will come from, I have no idea. But without that, we will continue to live blindfolded, amplifying fear, uncertainty, and doubt in our echo chambers, and thinking that we live in Mordor where cybercrime losses will constitute $1 novemdecillion by 2030. We need data, and we need numbers, but we should stop creating them out of thin air, just to get backlinks and to get quoted in major media outlets. As an industry, we can do better.

Another great piece Ross. A recent straw poll from fellow front line security types (a closed door session with one or two incident response providers) suggests 70% to 90% don’t announce when affected by a “material” incident. This has certainly been my observation and whatever the percentage, a significant proportion is unreported. Also, the business impact of incidents has strayed into the domain of “death by a thousand cuts”. Since there’s not even a clear definition of the boundary of “Cyber” (other than the great CYBoK material from University of Bristol) the boundary of what gets counted, even if visible, is so distributed and often individually “small” that it would anyway fall out of view. What’s clear is this needs to become more disciplined, because the temperature has risen significantly over just the last 3 years (not a statistically relevant point just personal experience!).

Wow. Great post as always. Your ability to put into words what the collective security community knows and has harped on for years is unmatched. Keep up the great work, Ross!