Three critical but rarely discussed aspects of the security market

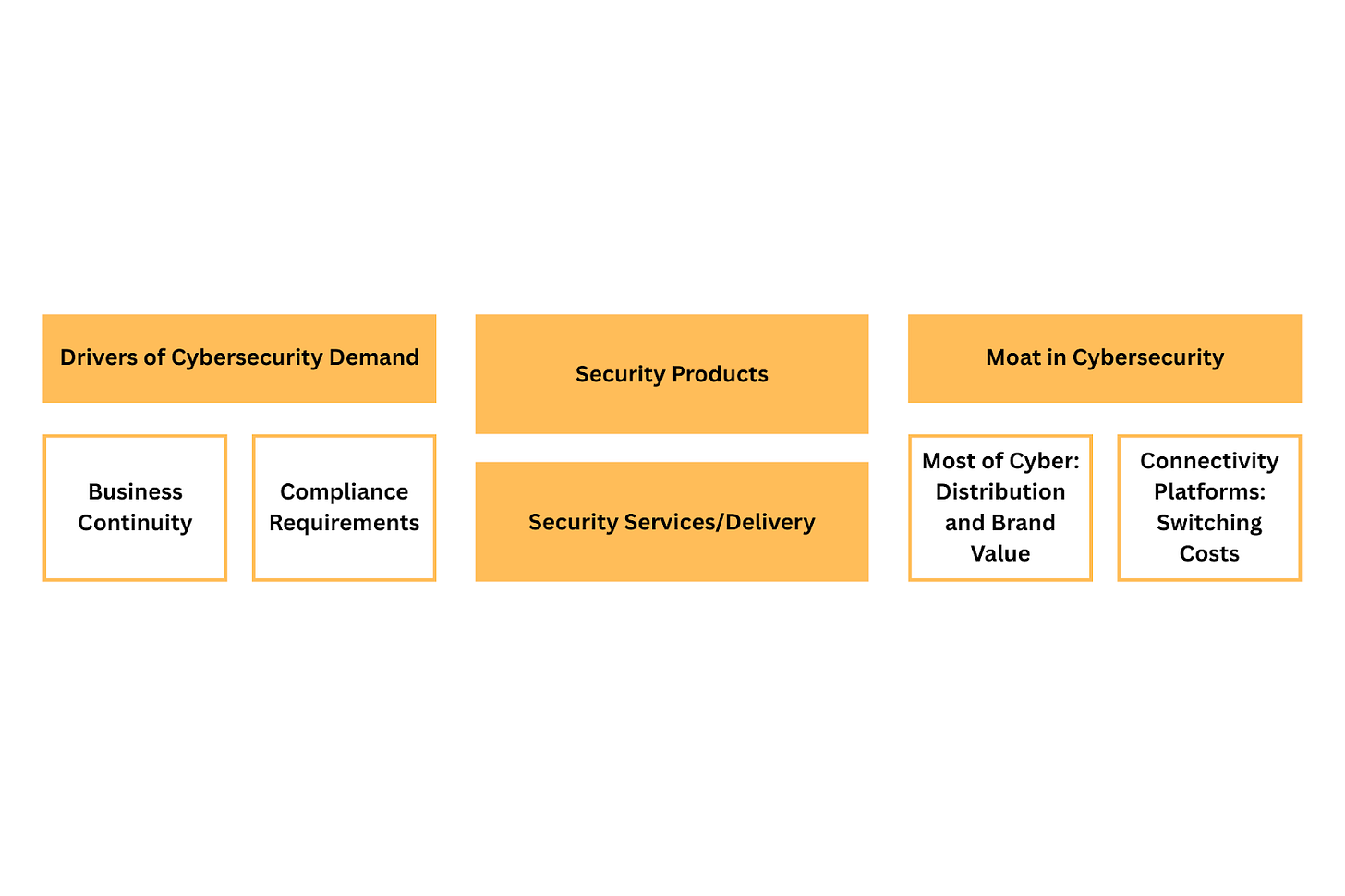

A brief take on three separate but very much connected topics: drivers of security demand, moat, and the importance of services.

I often discuss what makes security unique or different from other industries. Today’s article is another one in this series: I am looking at what the real drivers of cybersecurity buying are, how security is a services-first space, and how the moat has a different shape in security than it does in other industries. This week, I am doing something different and instead of writing a deep dive, I am publishing a brief take on three separate but very much connected topics.

This issue is brought to you by… Vanta.

VantaCon: Join the event in-person or virtually this November

AI is fast transforming every aspect of security and compliance—and no aspect of GRC will be left unchanged.

This year at VantaCon, join Vanta for a full-day GRC community event.

Be the first to hear exciting product announcements, discover how industry peers and leaders are preparing for big changes while uncovering unique opportunities for growth, and take part in new breakout sessions designed for collaboration—not just on what’s next for GRC, but how we’ll write its future together.

Join Nov 19 live in San Francisco or virtually to:

Hear from the GRC and security leaders shaping the industry

Network with the best

Help write the future of GRC

There are only two real drivers of cybersecurity demand

Why do companies buy security? Conventional wisdom is that it is to pretect the so-called CIA triad - confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data. I think this view is too simplistic, and it begs for more details.

Regardless of the industry, I have observed that business cares about one thing: protecting its ability to increase shareholder value. In practical terms, this means ensuring that the company can continue operating normally and therefore generating revenue, and ensuring that the company won’t incur unexpected monetary losses.

Ensuring continuous operations has two aspects:

Business continuity, or making sure that assets that produce value (people, equipment, etc.) are functioning as normal. This is why ransomware is such a big deal - when a business stops producing whatever it is producing, it stops making money.

Mandatory compliance requirements (SOX, etc.) are met and certifications required to establish trust with buyers (SOC2, etc.) are obtained. The difference between these two types of compliance is simple: the former allows the company to exist, while the latter allows it to sell.

Avoiding monetary losses also has two aspects:

Preventing significant penalties from being imposed on the business by the regulators.

Preventing the need for ransomware payouts, brand restoration, and so on.

The further away a security breach is from impacting a company’s ability to generate shareholder value, the lower it is on the list of business priorities. Data loss, for example, isn’t that big of a deal unless it leads to regulatory action that could prevent the business from being able to operate, or impacts revenue generation in a concrete way. If Coca Cola loses its coke recipe, it will matter. If Coca Cola loses the personal information of its employees… sadly not that much. Most cases of data loss will at best have a short-term negative impact on the stock price. Three months later, nobody will remember it even happened.

Some security purchases are dictated by compliance requirements. Third-party risk management and data loss prevention are good examples. For these, the market may be pretty decent but it is limited to companies that are required to comply with the certain regulatory regime. The more companies are affected, the larger the market. On the other hand, some security purchases are driven by the business needs to protect revenue generation and avoid losses. Ransomware prevention and response fall under this category. The Holy Grail of security are markets where the two buying motivations - compliance & business need - overlap. These markets are the largest as some people will buy the tool because they see a need to do so, while others will buy the same tool to check a box.

Last mile of value delivery in security is services-centric

When you take a closer look at some companies that have been successful as pure-play security offerings, it doesn’t take long to notice that these are often services-first companies. It’s not just service providers such as Arctic Wolf and Expel, but also companies commonly seen as product players that have been heavily leaning on services for go-to-market and outcome delivery. For example, CrowdStrike, a company targeting enterprises, was built on the backbone of services, as was Dragos, a company targeting the operational technology market, and Huntress, a company targeting small and medium-sized businesses. The percentage of revenue each of these companies generates from services varies, but being hands-on and working closely with customers has undeniably been the key to their success.

While this doesn’t apply to all security companies, it is also true that oftentimes, we don’t notice the delivery/services part because it’s been well hidden. Even when the product company itself choses not to focus on the delivery and/or continuous service aspect, someone still has to help customers operationalize products they buy. This work is often outsourced to channel partners (MSSPs, resellers, integrators, etc.) in a model that gives them the incentives to carry and/or resell a specific vendor, and then provide a recurring offering on top. However you slice it, there is usually some human doing the work.

This phenomenon is easy to explain: most customers simply have no idea how to secure themselves. They don’t have talent in-house to understand what their security needs are, let alone to take care of them. There is little value in trying to sell tools if customers can’t make use of these tools. Hands-on support (aka services and delivery) are the most important part of security, and they are (and for the time being, will continue to be) largely manual.

Moat in security has a rather unique shape

Pure-play security companies don’t have technical moat but they compensate for that with something else

Most cybersecurity companies don’t have a technical moat. The reason that is the case is simple: security is a layer on top of the underlying infrastructure, and therefore it can be easily swapped out.

The consumerization of technology has led to the situation where buyers are looking for a quick time to value. Gone are the days when a CISO would be open to deploying agents or setting up gateways to onboard a security product; nowadays, unless a product can show value after a few short clicks, it will most likely never get adopted. I have seen countless examples and heard many more stories about security leaders trading supposedly better coverage for ease of use and lower total cost of ownership (TCO).

The push for a short time to value comes with trade-offs for startups. On one hand, the quicker the customer can onboard the tool, the more likely it is that the product will be able to win POCs. On the other hand, faster onboarding time usually also means that it’s easier to replace the product in a year or two when something more consolidated or cheaper comes along.

Instead of developing technical moat, pure-play security companies do two things:

Develop distribution channels.

Develop perception on the market that they are a safe choice for buyers.

In combination, these two initiatives, if executed successfully, can provide a long-lasting advantage against competitors. Security is a market for silver bullets, and therefore being able to maintain the leadership status in Gartner MQ or Forrester Wave creates a flywheel where successful companies only become more successful.

Connectivity-focused companies see switching costs as their main moat

First and foremost, it’s important to state clearly that companies such as Okta and Zscaler are not simply security vendors. Their value proposition isn’t to secure something, but to ensure that people can access what they need to access for them to be able to do their jobs. It is true that they need to do so securely, and to achieve it they may add all sorts of security capabilities, but that alone doesn’t turn them into security-only vendors. If it did, then cloud providers, API vendors and others would all be considered security companies. Instead, to these companies security is a part of their value, but not the only value they are able to offer.

This distinction is very important because companies focused on connectivity are subject to different types of risks and enjoy different types of benefits compared to security companies:

Identity providers such as Okta are critical for employees to be able to access the resources they need to do their jobs. An Okta outage can make it impossible for the whole company to function. The stakes are incredibly high, and so is the bar for the level of trust a customer would need to adopt an identity provider.

Network proxies and firewall vendors such as Zscaler and Palo Alto define who can access what and under what conditions. A Zscaler outage can paralyze the whole company and therefore the expectations around uptime and availability are very high.

To put this simply, if a data loss prevention (DLP) tool has an hour-long outage, it could miss some bad behavior that may (or may not) happen during that time. It’s not great, but it’s also not as bad as having the whole company lose potentially millions of dollars because nobody can do anything for a full hour.

This heightened level of expectations presents an opportunity to establish an incredibly strong moat. The core of this moat is insanely high switching costs. While companies may be willing to swap out a DLP, an employee security awareness training platform, or a cloud security posture management (CSPM) tool, no IT leader in their right mind is going to come to the CEO and say “I think we should rip out the infrastructure that connects all the employees to their work because there is a new vendor out there that is 20% cheaper and it has some features that Zscaler doesn’t”. The bar for displacing connectivity vendors is much higher than the bar for displacing security vendors. Just because Okta got breached several times, it does’t mean that many companies would get the guts to replace it (even if there was a viable alternative out there which today I’d argue there isn’t).

Closing thoughts

I feel like almost every week, I go back and forth on whether our industry is unique, or if it’s the same as others with just some unique aspects. This week I am once again looking at the uniqueness of our industry. It’s easy to see that security is shaped by different forces than most other fields: buyers are motivated by tangible risks to revenue and compliance; successful vendors heavily rely on services or partners to deliver outcomes customers can’t achieve alone; and moats are built not on technology alone but on trust, distribution, and indispensability. When you look at all this together, it becomes clear that our market behaves the way it does for a long list of reasons, and that winning in cyber requires a playbook that’s different from almost anywhere else in tech. And still, nothing in my opinion explains the market better than the paper on the market for silver bullets.

"and Hunters, a company targeting small and medium-sized businesses." - I assume this is Huntress?

And offhand, another market that shares some similarities to cybersecurity would be specialized medical equipment. Very regulatory/legal (HIPAA/malpractice avoidance), but with some chasing of silver bullets (AI imaging! Surgical robots!) and the accompanying heavy services push. Definitely much harder to switch out, though, so longer sales cycles, higher margin, etc.