Mental models for cybersecurity startup founders and why Microsoft cannot easily force nimble early-stage companies out of business

Discussing several mental models for cybersecurity startup founders and explaining why Microsoft cannot easily force nimble early-stage companies out of business

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Also, over 1,200 copies of my best selling book “Cyber for Builders: The Essential Guide to Building a Cybersecurity Startup” have been delivered by Amazon so far. This book is unique as it talks about building cybersecurity startups. It is intended for current and aspiring cybersecurity startup founders, security practitioners, marketing and sales teams, product managers, investors, software developers, industry analysts, and others who are building the future of cybersecurity or interested in learning how to do it.

When discussing new cybersecurity startups, I often hear that “A company is doing something interesting but it is doomed because Microsoft, Cisco, Palo Alto, [ insert your favorite large vendor ] can easily build the same solution”. Moreover, I keep seeing early-stage startups start by trying to sell to the largest and slowest-moving enterprises, just to realize a year (or two) later that they have wasted precious resources and lost focus without much to show for it.

In this piece, I am discussing several mental models for cybersecurity startup founders and explaining why Microsoft cannot easily force nimble early-stage companies out of business.

Innovator's dilemma and its significance for cybersecurity

The innovator’s dilemma: key ideas

When looking at early-stage startups and new ideas, many security practitioners, especially those who have been in the industry for a decade or longer, often say the same phrase: “That sounds like a great idea, but Microsoft can easily build it, and when they do, the startup will go out of business”. Depending on the market segment in question, you can substitute Microsoft for Palo Alto, Snyk, Cisco, or any other top player that seems to have all the resources in the world, and the ability to decide what the future is going to look like. Yet, despite this seemingly pre-defined destiny, things rarely go the way believers in large corporations forecast. McAfee, a company that was founded in 1987 and went public five years later, for many decades remained one of the largest cybersecurity companies in the world. Symantec, another cybersecurity giant founded back in 1982, was recognized by Forbes as the largest cybersecurity company by revenue as recently as 2017. In 2024, it would be hard to find people who are looking to McAfee and Symantec to help build the future of cybersecurity, but a few decades earlier, they were certainly seen as inevitable winners in the market.

The reason McAfee is not launching industry-defining cybersecurity products is the same as the reason why BlackBerry which once controlled over 50 percent of the global smartphone market now has just above 0% of the market, and why people in 2024 are looking to buy Macbooks, not IBM workstations. This reason is called “the innovator’s dilemma”.

The concept of the innovator’s dilemma was first introduced by Clayton Christensen. In his book, The Innovator's Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail, he explained:

“The reason [for why once leading companies failed] is that good management itself was the root cause. Managers played the game the way it was supposed to be played. The very decision-making and resource allocation processes that are key to the success of established companies are the very processes that reject disruptive technologies: listening to customers; tracking competitors' actions carefully; and investing resources to design and build higher-performance, higher-quality products that will yield greater profit. These are the reasons why great firms stumbled or failed when confronted with disruptive technology change.

Successful companies want their resources to be focused on activities that address customers’ needs, that promise higher profits, that are technologically feasible, and that help them play in substantial markets. Yet, to expect the processes that accomplish those things also to do something like nurturing disruptive technologies – to focus resources on proposals that customers reject, that offer lower profit, that underperform existing technologies and can only be sold in insignificant markets– is akin to flapping one’s arms with wings strapped to them in an attempt to fly. Such expectations involve fighting some fundamental tendencies about the way successful organizations work and about how their performance is evaluated.”

It is commonly assumed that the reason incumbents fail to develop innovative technologies is that people who work there lose the ability to identify trends, come up with new ideas, and build innovative solutions. The opposite is true: large corporations employ the top talent that is first to spot new trends and come up with ideas about new solutions. The problem is that they try to apply it to their existing customer base, and that’s not where the true innovation starts. In many cases, embracing a new idea would mean undercutting a well-established revenue channel and disrupting the company’s own products - something good management has strong reasons not to do. In the beginning, disruptive innovations rarely offer profit margins that make sense to pursue, and they rarely originate in Fortune 1000 companies large vendors spend most of their time listening to and building for.

Image Source: InnovationManagement.se

The reason new entrants win is that they are able to identify problems of niche customer groups and invest in solving them really well, better than any incumbent could. Moreover, since they are not locked into technical architectures from decades ago, and they don’t have a large number of existing customers that need to be kept happy, they can be scrappy, ruthlessly prioritize, and use the latest and greatest ideas to build on. The incumbents have high expectations of yearly sales, and all their planning has to focus on achieving these numbers. Since startups do not have to conform to the same expectations, they have more time to solve the problems of their niche customers well.

Innovator’s dilemma in cybersecurity

It is easy to argue that Microsoft or Palo Alto, to name some, could easily solve any security problem. After all, they can afford to hire the best talent, and once the product is ready, they can plug it into their well-oiled distribution channel and just start selling.

The reality is a bit more complex. Although large enterprises are where most of the money on security is being spent, a very small percentage of them can be thought of as early adopters of security innovation. This means that for top cybersecurity companies, it is hard to prioritize solving security problems of the small market instead of listening to requests of the companies responsible for generating the biggest chunk of revenue.

Even if an incumbent decides to invest in solving a niche problem, it won’t automatically become a winner in the space. First and foremost, large software companies have complex planning and budgeting processes. Security startups aren’t competing with Microsoft or Palo Alto - they are competing with a small product team of 10-20 developers, and a product manager operating within the bureaucracy and hierarchy of large corporations. While a startup founder can talk to five prospects and ship an early version of the product next week, a product manager at Microsoft needs to go through several chains of discussions to gather stakeholder feedback, finalize the roadmap, plan resources, iterate as new learnings come in, etc.

For a startup, the problem it is solving is the only thing the whole team focuses on. For Microsoft or any large software provider, the same problem is just one among 3,500 other problems the company is tackling. The degree of commitment also differs. Employees at large corporations, with some exceptions, will finish their day at 5 or 6 pm, while startups will work around the clock, on weekends and evenings, to make new ideas happen. For early ideas, speed is critical: the faster the team can move, the quicker it can learn, and the better the product will be. This is not even taking into consideration the fact that incumbents have to deal with decades of technical debt that is always going to prevent them from being able to move fast and leverage new technologies.

In cybersecurity, the innovator’s dilemma has two additional layers: talent and industry direction. Addressing threats in new areas requires talent that is often not readily available at large enterprises heavily invested in defending against attacks in the old stack. When the number of mobile devices exploded, companies with deep expertise in endpoint, and in particular, Windows security, didn’t have the people experienced in mobile. This is where startups often have an edge. More importantly, there are many types of attacks, and adversaries are working relentlessly to identify and exploit security gaps in ways that have not previously been seen before. No large company can anticipate all the ways in which the industry can develop. Small startup teams, on the other hand, have the ability to identify new trends early and go fully into pursuing their vision for the future. While in many cases, their hunch may lead them astray, eventually savvy practitioners will be able to anticipate where the innovation is needed and outcompete the incumbents in solving these problem areas.

Large corporations, especially platform players such as Microsoft and Palo Alto, do have a lot of advantages, including the ability to upsell their existing customers by leveraging well-established distribution networks and offer a single, consolidated experience that reduces the need for stitching together multiple disjoint solutions. Microsoft, in particular, has been able to establish itself as the largest cybersecurity player thanks to its strategy of bundling security with its other offerings. While these are indeed important for success, the reality of security is that in new problem areas, customers are quite open to leveraging best-of-breed solutions that offer better protection. If startups can build better solutions than those offered by the incumbents, they could stand the chance to become visible players in the market. While Microsoft could, in theory, own the whole security market, the reality of the industry, to a large degree shaped by the impact of the innovator’s dilemma, is that there is enough space for nimble and ambitious startups to get their piece of the pie, and even grow into industry leaders.

The Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and its implications for security

The Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: key ideas

In 1943, the American psychologist Abraham Maslow proposed an idea that became known as Maslow's hierarchy of needs. This theory is based on the premise that in order to become motivated to pursue higher-level needs, an individual must first meet their most basic needs. Maslow's work is most commonly illustrated as a pyramid, although notably a pyramid was not his creation and does not appear in any of his work.

At the bottom of the pyramid are physiological needs, followed by the need for safety and security. Once these basic needs are satisfied, a person is likely to strive to fulfill their psychological needs for belonging, love, and a sense of accomplishment. At the top of the pyramid is self-actualization which is seen as an ultimate stage for fulfilling one’s full potential. Not everyone in their lives is fortunate to get to the point where they can start thinking about self-actualization.

Image Source: Wikipedia

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in cybersecurity

There have been many articles about the application of Maslow's hierarchy of needs to cybersecurity. Below are just some of the examples; a quick internet search will show that there are many more.

Image Sources: Medium, LinkedIn, Forrester, and SCVO

I am not here to argue which of many pyramids looks the most relevant. Instead, I would like to discuss the implications of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs for security startups. There was a time when what is known today as major attack vectors was new. Whether we are talking about endpoint security, network, code, cloud, or anything else, there were no solutions on the market that could address threats known in these areas. When a new startup would emerge to tackle a problem area, their main challenge was educating the market about needing to worry about the attack vector. Moreover, startups had large problems to solve, and the best way to do it was to build must-have capabilities, gain market share, and then slowly go to nice-to-haves. They still had to pick the right wedge, etc. but they were tackling large problem areas and had much more flexibility doing it.

Fast forward to today, and one may argue that in terms of tools, the fundamental security needs have been covered. Although not every enterprise is doing security fundamentals well, and most are still struggling with basics, we do have solid tooling for endpoint security, asset management, vulnerability management, and other problem areas. When most startups today are looking for a wedge that would enable them to enter the market, they are mostly looking at nice-to-haves - solutions for the top most mature percentage of the market. Opportunities for taking a large problem area (say, endpoint) and building a solution for the mass market are largely gone due to the growth of platform players such as CrowdStrike, Palo Alto, Microsoft, and others. Although this fact does not necessarily mean that no innovation is possible in existing categories, a company would need to bring something impressively novel to the table, not to come in as a “yet another X tool, but surely better than what’s already out there”.

When founders are starting their companies today, in most cases they are faced with a tough question: can the area they are starting with, which is a nice-to-have for a small customer segment today, quickly become a must-have for the rest of the market tomorrow? Some bets see higher rates of adoption than others: multi-factor authentication, for example, has gained a much wider adoption than detection engineering and building custom detections for every organization’s environment.

The issue is that it is not easy to discern if:

There is a large total addressable market (TAM) but the reason the company is struggling to attract customers early on is that only a few meet the profile of early adopters, or

The market is small, and those 10-50 customers are everything the startup can hope for because the solution is nice to have for a very small segment of the market.

Diffusion of innovations and its significance for cybersecurity

Diffusion of innovations: key ideas

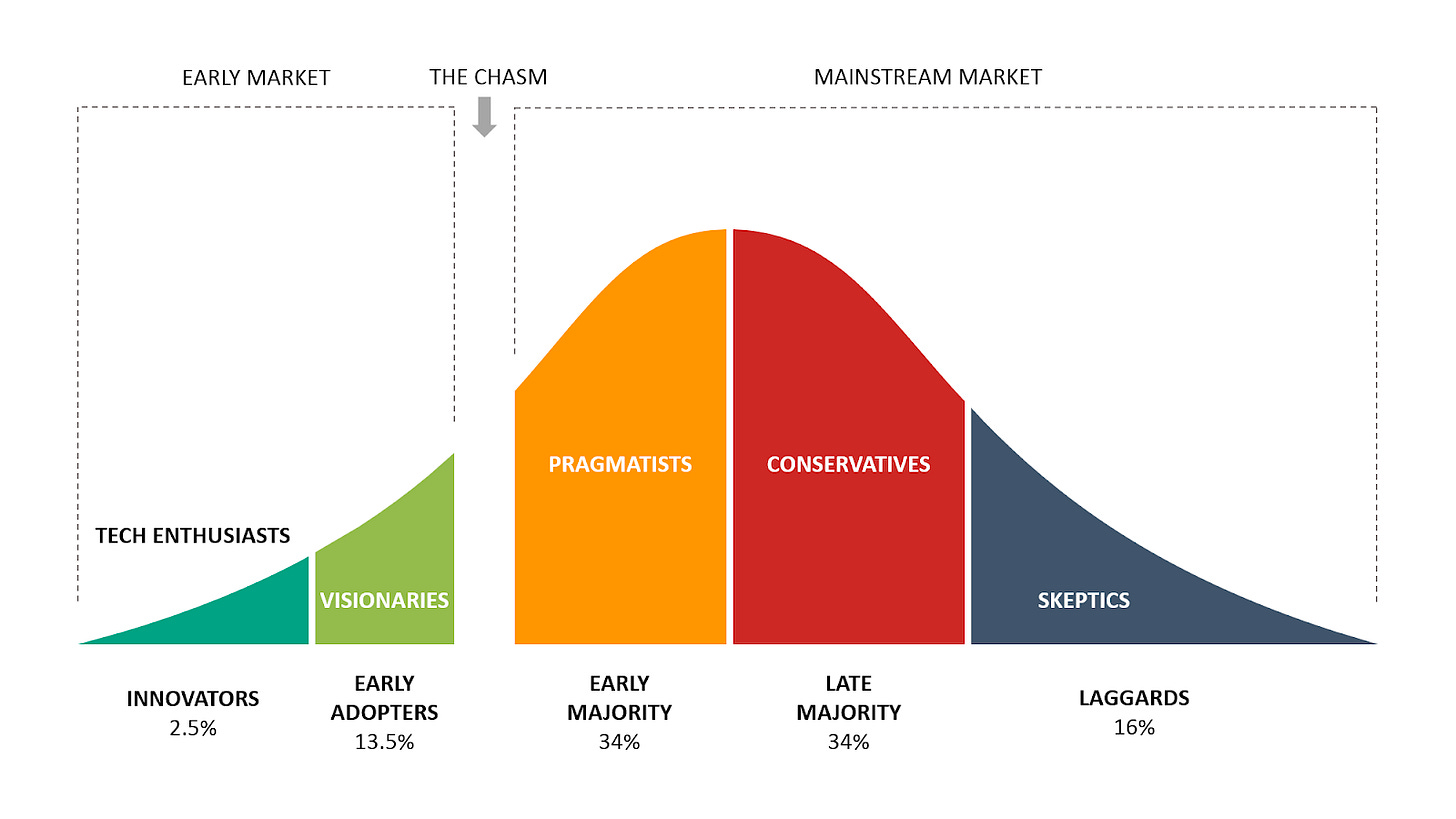

The diffusion of innovations theory developed by Everett Rogers describes the way new ideas, concepts, or products gain adoption. According to this theory, the population is divided into innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards.

The diffusion of innovations theory was expanded and adapted by Geoffrey Moore who in 1991 published a book “Crossing the Chasm: Marketing and Selling High-Tech Products to Mainstream Customers”. Building on the ideas of Everett Rogers, Geoffrey Moore argues that there are two markets for anything new: an early market, and a mainstream market. Innovators are technology enthusiasts always on the lookout for new ideas and approaches, and they like to be the first to try and test every one of them. They, along with early adopters who are visionaries capable of recognizing the promise of new ideas quickly, constitute the early market for a product, a service, or an approach. On the other hand, early majority (pragmatists), late majority (conservatives), and laggards (skeptics) form the mainstream market. The author explains that there is a chasm between the early adopters of the product (the technology enthusiasts and visionaries) and the early majority (the pragmatists). To cross this chasm and to successfully grow the company beyond a few early enthusiasts, startup founders have to be deliberate in how they approach their go-to-market and embrace a step-by-step approach to user adoption. For anyone building an early-stage startup, or thinking of starting one someday, I cannot recommend Geoffrey Moore’s book enough.

Image Source: Crossing the Chasm in the Technology Adoption Life Cycle

Crossing the chasm for cybersecurity startups

Geoffrey Moore’s theory is highly relevant to cybersecurity, even if I would say that some factors make our industry look a bit unique. In cybersecurity, the innovators are that small percentage of organizations with the highest levels of security maturity. Often these are security teams with an engineering mindset that are always on the lookout for new ideas and solutions to further strengthen the security posture of their organizations. Cybersecurity innovators are building their own solutions in-house, open-sourcing some of their stack, and presenting new ideas at conferences such as BSides and DEF CON.

Once the new approach proves relevant to the broader circle of enterprises, that’s when we see early adopters - companies with fewer resources but also a high level of security maturity step in.

The vast majority of the enterprise customers could be defined as pragmatists, while a good percentage are the late majority. In the SMB space, the vast majority are skeptics (laggards) with respect to security. To get conservatives and skeptics to implement new approaches to security, government regulation or insurance requirements are usually needed. If a control is not mandated by either of the two parties, it is unlikely to get mainstream adoption.

In every customer segment, some organizations are less likely to buy from security startups. Large, risk-averse, and slow-moving enterprises that only buy their solutions through channel partners are much less likely to sign a deal with an early-stage security startup and deploy its solution in their environment.

Established enterprises are looking for enterprise-grade tools, and pre-seed or seed-stage companies can rarely meet these requirements. Instead of trying to go through a year-long proof of concept (POC), early-stage startups are better off finding customers who are comfortable with what it means to work with a newly formed company. They need to be willing to deal with bugs, provide feedback, work with founders to improve the product, and help the company succeed. In other words, they need to be innovators and early adopters of security solutions. It is worth noting that some large enterprises have dedicated budgets for innovation and experimentation, and could very well be great partners to early-stage companies. Founders must understand who they are talking with, and focus their efforts on areas where they are most likely to get the best return on investment at the stage they are at.

When an early-stage founder talks to security leaders and practitioners about their approach and sees some interest, it is too early to go all in, raise capital from investors, and build a solution. Founders must understand what is it that makes these people excited:

Are they just being nice and looking to encourage the founder to keep going? People do that all the time. For anyone looking to get better at conducting customer discovery and reducing bias as much as possible, I highly recommend reading “The Mom Test” by Rob Fitzpatrick.

Are they innovators or early adopters in a large market?

Are they innovators in a smaller market?

Are they a small percentage of security teams so high up in the previously discussed Maslow’s hierarchy of needs that they are looking for solutions to problems nobody else is going to be solving for decades to come?

There could be plenty of possible explanations, so founders must challenge their assumptions and try to understand, among other things,

Who they are talking to.

If a certain prospect is one-of-a-kind, or a representative of a group.

The number of other organizations that could be a part of that group.

Factors that impact the urgency or the perceived urgency of the problem.

Whether these factors are shared by all companies in the group or just some of them and why that is.

The key risk for startups and de-risking cybersecurity innovation

To succeed, startups need to de-risk their riskiest assumptions as early in their lifecycle as possible. In my view, the best way to start is to use the limited resources to validate the number one risk for the company. Two of the most common key risks faced by cybersecurity startups are distribution and product.

Based on my observations, most cybersecurity startups fail because of their inability to establish scalable and replicable distribution channels. In 2024, the idea that a company can focus on building a great product and then people will just buy it is laughable: the industry is insanely competitive, and in every category there are plenty of alternatives, most often poorly differentiated. Distribution is key, and early-stage cybersecurity startup founders would be better off to start by doing what they can to de-risk distribution, be it validating demand, testing different go-to-market strategies, and looking for what could work in their market.

There is also a small subset of cybersecurity startups for whom the key risk is product. These are, by and large, deep tech innovations where technology is so uncertain, that it is highly questionable if the company can build a product. The reality for most cybersecurity startups is that product is not their biggest risk: there is an established pattern for tackling the vast majority of the industry problems, so much so that technology rarely constitutes the largest area of uncertainty.

One of the most commonly seen problems in security is that founders jump right into building products, without realizing that their key risk is distribution. Instead of spending time validating demand, building an understanding of how customers in their market buy solutions, and talking to CISOs and security practitioners to find other non-obvious ways to get their product into customers' hands, cybersecurity startup founders go deep into figuring out the best feature to add. The vast majority therefore ends up with great solutions nobody is buying.

Dealing with factors outside of the startup’s control: market & economy

Many factors impact startup success. While some, such as the ability to execute and find product-market fit, are generally under the founder's control, many others aren’t. Two of the factors with the highest potential of impacting the company destiny that cannot easily be changed by the founders are the state of the market and the state of the economy.

Picking the right market segment is crucial to success. This is because:

Different market segments require different go-to-market strategies, have different buyers, and are impacted by different industry trends.

Most market segments in cybersecurity are too small for companies to achieve IPO scale and go public.

Some market segments are shrinking while others may be small today but are expanding.

Startup founders must understand their market - not just how big the experts project it to be in the coming years, but also what the headwinds and tailwinds in the segment look like, what trends are impacting its direction, how products in the segment are usually adopted, how high the switching costs are, how much urgency the security team has to deal with the problems, and so on.

When it comes to the economy, the degree to which it can influence the chances of success is highly dependent on the stage of the company. For early-stage startups, the state of the economy matters very little. If a prospect is experiencing a very painful problem, they will be willing to move forward with buying a solution from an early-stage startup without worrying about the budget. On the other hand, if a startup is not solving a “hair on fire” problem for a well-defined customer segment, it is unlikely to gain traction regardless of how the economy is doing. Pre-seed and seed startups with a solid team, strong growth signals, and enough early customers to validate that the company is onto an impactful problem, also don’t usually have any issues raising funds.

The later the stage of the company, the more the state of the economy matters to its success. If the economy is not doing well at Series A or Series B, when the startup is supposed to expand and hire sales teams, it's more likely that sales will miss their quotas and the company will struggle to hit the milestones it needs to hit. It gets even worse if the company’s preparations for an IPO coincide with economic downturns and closed IPO windows. This increases the chances that the startup will need to seek additional capital to weather the storm, either taking on venture debt or diluting its existing shareholders by selling equity.

Closing thoughts

We are used to thinking that cybersecurity is a one-of-a-kind industry. Although there are many ways in which that is the case, what is also true is that security is a part of the broader area of technology. Many other areas of technology provide us with mental models, ideas, and frameworks that can successfully be applied in security, and cybersecurity founders can certainly benefit from looking outside of security more often.