Learned helplessness is hurting the security industry

Cybersecurity is suffering from a severe case of learned helplessness, and we have to overcome it

Every several months, I come across an article, a LinkedIn post, or a talk that gets me annoyed, seemingly for no reason. I found this interesting, so several years ago, I started collecting these statements to which my brain responds with rejection into a single Google Doc. Whenever I’d hear or see someone repeat one of these statements, I’d drop them into this doc along with my thoughts at the moment, and go about my day.

Last weekend, when I opened this document and went over a few pages of links and my chaotic notes, it finally hit me that all the things I disagree with have a single root cause, and they are all the result of the same phenomenon - learned helplessness. In this piece, I’ll discuss this phenomenon in depth, explaining what it is, why I find it frustrating, and why I think that to mature as an industry, we have to move past it.

This issue is brought to you by… Vanta.

The GRC Event of the Year: Join VantaCon Virtually

Tune in on November 19 to VantaCon, the GRC event of the year! Speakers from Vanta, Anthropic, 1Password, Sublime Security, and more will be tackling the big problems security professionals are facing today, and the opportunities new technologies and trends are uncovering for the future.

At VantaCon you’ll:

Build connections with 400+ peers in the GRC security space

Learn from a wide range of GRC community professionals sharing insights & best practices from companies big and small

Get hands on with labs and learning opportunities to sharpen your skillset and take new ideas back to your organization

Register today to watch the VantaCon livestream and participate in the virtual Q&A.

The concept of learned helplessness

Here’s how Psychology Today, the world’s largest mental health and behavioral science destination online, explains the concept of learned helplessness: “Learned helplessness occurs when an individual continuously faces a negative, uncontrollable situation and stops trying to change their circumstances, even when they have the ability to do so. For example, a smoker may repeatedly try and fail to quit. He may grow frustrated and come to believe that nothing he does will help, and therefore, he stops trying altogether. The perception that one cannot control the situation essentially elicits a passive response to the harm that is occurring.”

This is surely many smart words in a single paragraph, so the way I would explain it is much simpler. Learned helplessness is when people stop trying because they feel like their actions simply don’t matter. After trying and failing many times, they start to believe nothing they do will change things. It’s like giving up before you even start: even when people could actually find a way to fix the problem, they don’t because they stop trying.

Once you realize that this is a real concept, and once you see how it applies in security, I think you won’t be able to un-see it. Instead of me trying to convince you of this, let me just walk you through a few things people in security like to say that illustrate this problem really well.

Things people in security like to say that illustrate learned helplessness in action

“Attackers only need to be right once, defenders need to be right all the time”

This phrase has been repeated so often in cyber that it has become a kind of gospel. I remember a year or so ago, I said that things are a bit more complicated than this statement suggests, and a dozen people jumped in to tell me how wrong I am. People feel very defensive about this, and many will argue that it’s because it’s true. And yet, if you look closer, it becomes obvious that this “Attackers only need to be right once, defenders need to be right all the time” mantra reflects learned helplessness - the belief that defenders are going to fail no matter what they do. This idea sends the message that security teams can never truly win, only delay the inevitable.

There are better people than me to make this argument, but I hear this saying so often that I feel like I simply have to comment. I strongly believe that the idea behind this phrase is the clearest case of learned helplessness. When security teams internalize this mindset, it discourages creativity, risk-taking, and investment in proactive defense. Instead of seeing progress as possible, it frames defense as a losing game.

The most important part is that this phrase, while it sounds catchy, is wrong. Think for a second how defense works in practice: attackers will try different things, and they have to be right several times to execute the attack chain. To achieve their goals, attackers will have to pass through different barriers and layers, where each layer introduces complexity and reduces their chances of success. The more noise they make by being wrong, the more signals they send to defenders, and the easier they can get caught. I’d argue that defenders only have to be good enough one time to detect them and take action. Every patch, every detection rule, every segmentation improvement, and every training session raises the bar for attackers and makes it harder for them to be right enough times that they can just get in unnoticed.

On top of all this, the success of security isn’t defined solely by whether the attackers can get in. To a large degree, it’s a question of how long it’ll take for security teams to detect bad actors, how quickly they can respond, and how much time will be needed for them to recover, things security teams can continuously improve without sliding into the defeatist mindset.

“It’s not if, it’s when”

While the “Attackers only need to be right once, defenders need to be right all the time” gospel makes it sound like there’s nothing security teams can do, this whole “It’s not if, it’s when” takes that to the next level. Another variation of this saying that is equally defeatist is that “There are only two types of companies: those that have been breached and those that don’t know they have been breached.”

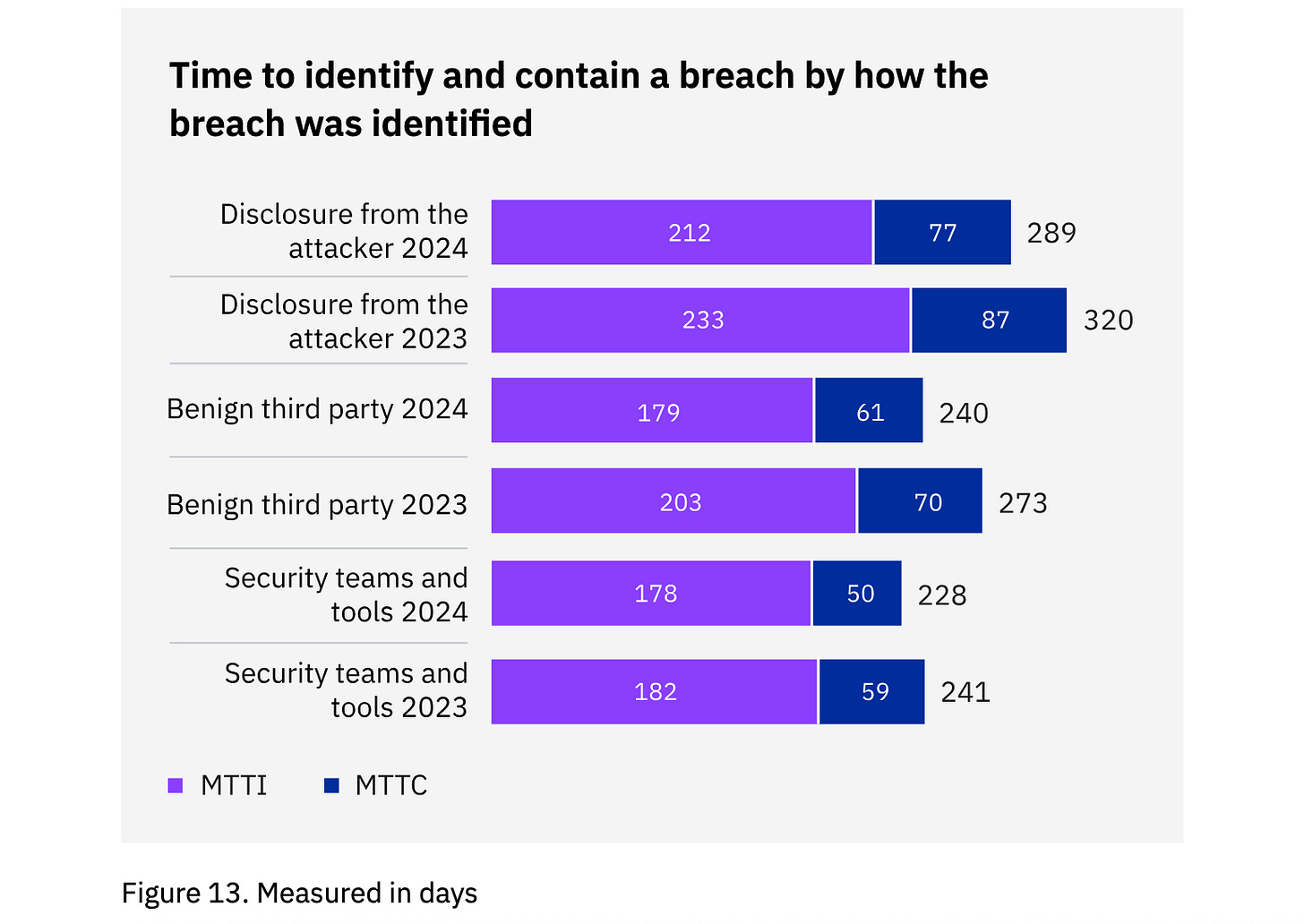

It’s very interesting to talk about this because I do see the point people who repeat these statements are trying to make, and I am sure they’re coming at it with good intent at heart. Take the fact that, according to the recent IBM report, it takes companies ~170-200 days to identify the breach (it’s worth noting that this report does suggest a slight improvement between 2023 and 2024).

Image Source: Cost of a Data Breach Report 2024

And yet, I think these sayings don’t push companies to invest in proactive threat hunting as much as they normalize defeat and make everyone accept that breaches are going to happen regardless of what we do. Over time, this mindset creates a sense of fatalism, and security becomes less about building measurable, improving programs and more about waiting for the inevitable breach.

I think the right takeaway should be to be prepared, not that everyone is doomed. Think about it: how can we as an industry expect businesses to take security more seriously if we’re the ones pushing the narrative that breaches are going to happen regardless of what we do? From a business executive’s perspective, if a breach is guaranteed no matter what, then the logical choice is to spend just enough to stay compliant, not to invest in real security improvement. I don’t know if most security people realize that, but we as an industry are pushing the self-destructing narrative that cuts security budgets and makes us look optional.

“People are the weakest link.”

Of all these defeatist sayings, my least favorite statement is “People are the weakest link”. I have written extensively about this in other articles, like The business of protecting individuals: realities of consumer-focused security, why we cannot expect that people will buy security tools, and what we need to do instead. In that article, I shared the following take: “Although the business of protecting individuals and getting individuals to help protect businesses looks like separate problems, they have common causes: our human nature. There is a long list of cognitive biases we are affected by, coupled with our innate drive to avoid pain and run away from friction, and our inability to understand risk, to name a few. For decades, the cybersecurity discipline focused on solving technical problems, dismissing people as “the weakest link” and assuming that simply forcing them to become more “aware” of security is going to magically change their nature.

This is not going to happen. One of the core reasons adversaries win against security teams is that they understand people, their fears, motivations, and behavioral drivers, and they learn how to exploit them to achieve their goals. When people are urged to act quickly, when they are threatened, when they are curious or afraid, they tend to act irrationally. No security awareness is going to change that.

The first step for us to design a more secure future is to embrace human nature and design security for it, not against it. First and foremost, this means designing security measures with a full understanding that people will always look for the easiest way to accomplish their goals. It also means accepting the fact that we cannot expect consumers to buy separate security tools - we need to build security into the current infrastructure and make it a default (and the only) option.”

At the end of the day, security teams are hired to protect organizations and their people, and protecting people means embracing their biases and behaviors, not rejecting them. Historically, security solutions have been designed to protect systems, but behind every system is a human.

Similar to the other phrases I discussed here, my issue here is less about the saying “People are the weakest link” itself, and it’s more about what it encourages and enables. That’s the real difference. Acknowledging that humans are fallible is important, but it should drive us to design systems that anticipate mistakes, not blame them after the fact. The phrase itself isn’t the problem; it’s how we interpret and apply it. In theory, we could say that “People are the weakest link, so we are going to do everything possible to invest in user experience and secure design patterns to safeguard them from harm”. In practice, more often than not, it sounds more like “People are the weakest link, so no matter what we do around security, some dumb employee is going to click a link and we’re done - does it even matter what we do?”. The same defeatist mindset, just in a different context.

An urgent need to fight learned helplessness in security

What the future of our industry is going to be is going to be largely dependent on what mindset we’re approaching it with. Over a year ago, I published a piece titled Cyber optimist manifesto: why we have reasons to be optimistic about the future of cybersecurity where I talked about the achievements we as an industry should be proud of, reasons why we are bad at celebrating success, and why there is an urgent need for cyber optimism. Before that, there was another one, about Hero culture in cybersecurity: origins, impact, and why we need to break the toxic cycle. Today’s article feels like a continuation of the series.

A lot has changed in our industry over the past several decades, but what remains the same is that we continue clinging to narratives that are holding us back. Learned helplessness and its manifestation in all the self-defeating stuff we think and say to ourselves is one of these narratives.

It doesn’t take long to realize that these narratives are hurting the security industry, leading to results we certainly don’t intend. Businesses are wondering why they should invest in security if it’s all going to fail anyway. Security professionals are questioning the meaning of their work because they feel “doomed to fail” no matter how hard they try. Meanwhile, ordinary people are tuning out, wondering why they should care about security at all if it’s so hard to understand and if everyone will get breached anyway.

The more we repeat these defeatist phrases, the more we reinforce the belief that security is unwinnable and that breaches are pre-determined, when in reality, there are many improvements and controls we can implement to meaningfully reduce risk. When we say things like “It’s not if, it’s when” and “Attackers only need to be right once, defenders need to be right all the time”, we think we’re being clever but what we’re really doing is sliding into mental shortcuts that make us all connectively sader, poorer, and less motivated to make a difference, at the time when we need enthusiasm and optimism the most.

I postulate that much of this learned helplessness is the direct result of reliance on detect and respond.

The key premise is that the timeline starts when an incident, vulnerability, exploit, or threat needs to be detected in order be actionable. That places the burden on the defenders, who are now permanently navigating alerts, and still getting surprised by things that evaded the security posture. No wonder people burn out and "assume breach", "when not if", attackers have the advantage, and many others.

For the longest while this was truth. With the advances in computing, big data, and the emergence of predictive AI, we can now predict attacks before they happen, and with good accuracy to avoid false positives. Not only this can be used to complement a traditional posture centered around detect and respond, it can also buy defenders the time to take a preemptive action on the threats. There's more innovation here, as the set of proactive and effective measures continue to expand: disrupt traffic to or takedown malicious infrastructures, block access from and to the network, move resources dynamically inside the network, or deceive attackers by providing bogus, synthetic data in their discovery or obfuscating the data in transit.

So more and more this is no longer a problem of capabilities or access to them; we can approach security in a different way. It's now a matter of mentality, and how much old narratives can still jeopardize a more modern and effective approach to security.

"everyone doomed to die" but it still have meanings of live. And yes "Attackers only need to be right once, defenders need to be right all the time”, but "defenders only need to detect in one place, attackers need to be undetected all the path", and finally "breach doesn't equal fail", security is about ROI and risk reduction.