How the top cybersecurity talent can immigrate to the United States

An in-depth guide for pursuing the EB1A Extraordinary Ability immigrant visa for cybersecurity practitioners looking to move to the US to help defend the nation from adversaries

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Also, over 1,675 copies of my best selling book “Cyber for Builders: The Essential Guide to Building a Cybersecurity Startup” have been delivered by Amazon so far. This book is unique as it talks about building cybersecurity startups. It is intended for current and aspiring cybersecurity startup founders, security practitioners, marketing and sales teams, product managers, investors, software developers, industry analysts, and others who are building the future of cybersecurity or interested in learning how to do it.

Introduction

This ebook masquerading as an article, unlike most of my other posts, is not going to be about the security industry. Instead, I will be discussing how the top cybersecurity talent can immigrate to the United States. If it is not relevant to you personally, I am sure you know people who would find it incredibly valuable. Please send them a link to this post or share this piece on social media. It’s an easy way to help someone achieve their dreams - they will thank you later.

Back in 2023, I had my immigrant application to the United States approved 10 days after I applied. It was just the first step on the long immigration journey, but that first step is the hardest one. Despite the fact that many friends and acquaintances assured me that going through immigration without a lawyer was a bad idea, I prepared the whole application myself, without spending a dime on attorneys and legal advice, and was granted the esteemed EB1A Extraordinary Ability visa approval, commonly known as “Einstein Visa”. I like to think I just got lucky. A few weeks ago, I finally received my green card. I am now a Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) of the United States.

Although the path I took is anything but simple, I am convinced that it is available to several people in my network, including some cybersecurity startup founders, tenured technical security professionals, cyber-focused investors, community leaders, and others. I am talking about people who run early-stage startups and have been accepted to accelerators, raised capital, or have paying customers. I am talking about those who run open source projects on the side that have been widely adopted around the world, those who build tools, present their research at Black Hat and DEF CON, and organize BSides, CTFs, and other events. Those who take time to write, give back to the community and move the industry forward. I have met many extraordinary individuals working in cybersecurity, and I hope this guide will reach the right people.

This guide is meant as a public service and I hope it will inspire the top cybersecurity talent to pursue their dreams, and if they choose to do so - to move to the United States. Instead of putting together an ebook (there are over 11,000 words in this “article”, all written without ChatGPT - imagine that!) and charging $250, or presenting my learnings as a course and charging $2,000 per seat as many others have done, I am making this available for free as a resource to anyone working in the cybersecurity field interested in immigrating to the United States. This isn’t because I am so awesome, but because I am where I am in life thanks to all the help of many people along the way, and I want to pay it forward. I am a big believer that those who can - should, and that success without integrity is a failure.

We badly need talented security practitioners to secure the future of our society. Only by bringing the top security leaders together and uniting them around a common mission, can the United States defend the values upon which our world is built - freedom, democracy, and the Western way of living.

Before I share my experience, and offer perspectives about immigration and how people can tactically prepare a successful green card application, there are a few critical disclaimers I want to get out of the way:

I am not an attorney, a lawyer, or a licensed immigration advisor. The information shared in this post is intended for general consumption and is not intended as legal, financial, or any other advice. Everyone’s situation is different, and you should always consult with professionals before attempting anything described here as a potential solution (YMMV). I assume no responsibility for the consequences of anyone using any of this information for any needs. Lastly, the information in this article may not be up to date with recent laws and regulations and I do not plan to keep it current.

I am not an accountant or a tax advisor, and this article does not constitute any form of financial advice. Please consult with a licensed accountant or financial planner because the tax implications of immigration might be dramatic.

This article does not cover anything related to bringing a spouse or children to the United States. When reading it, keep in mind that it is written from the perspective of someone single.

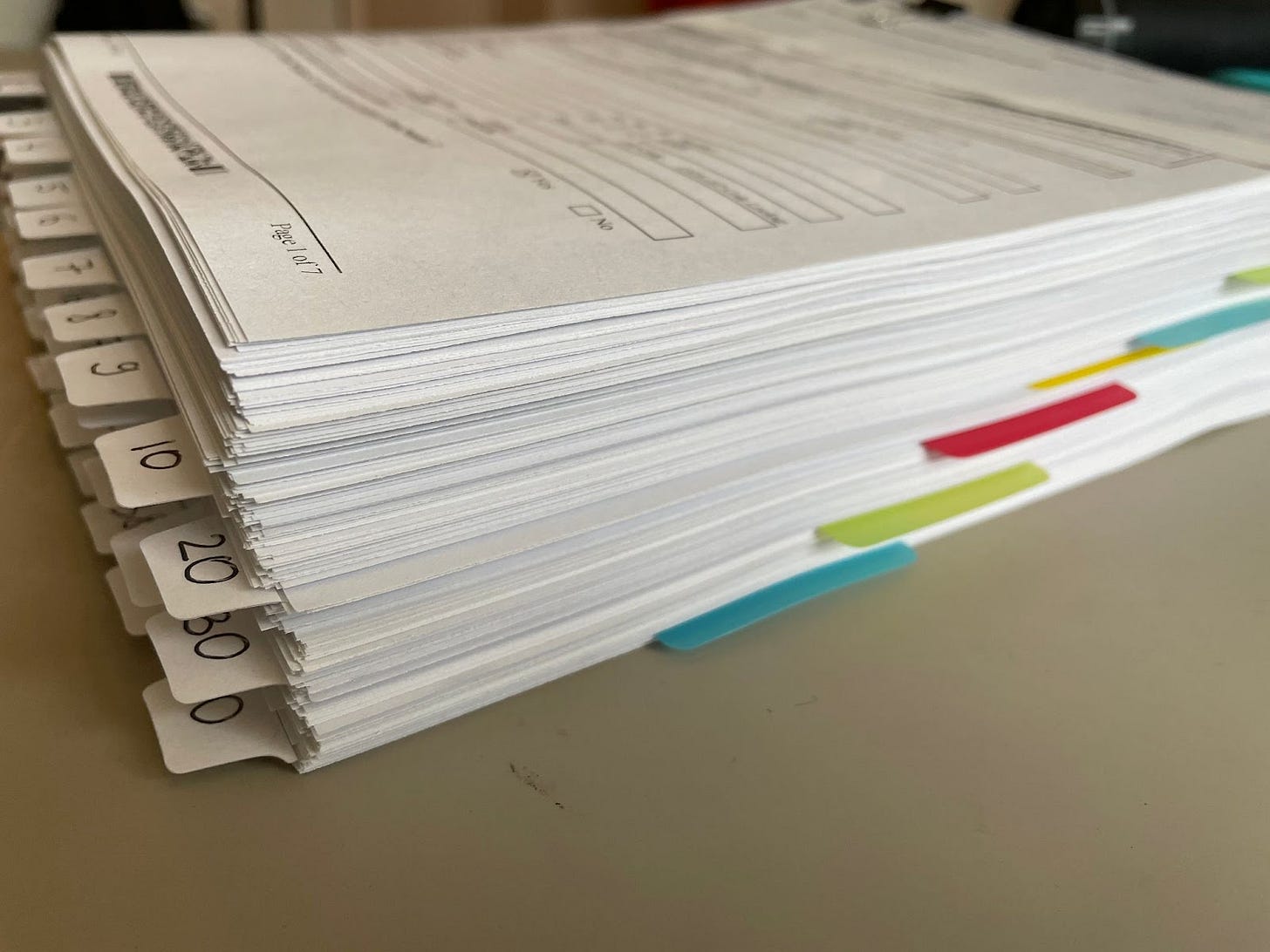

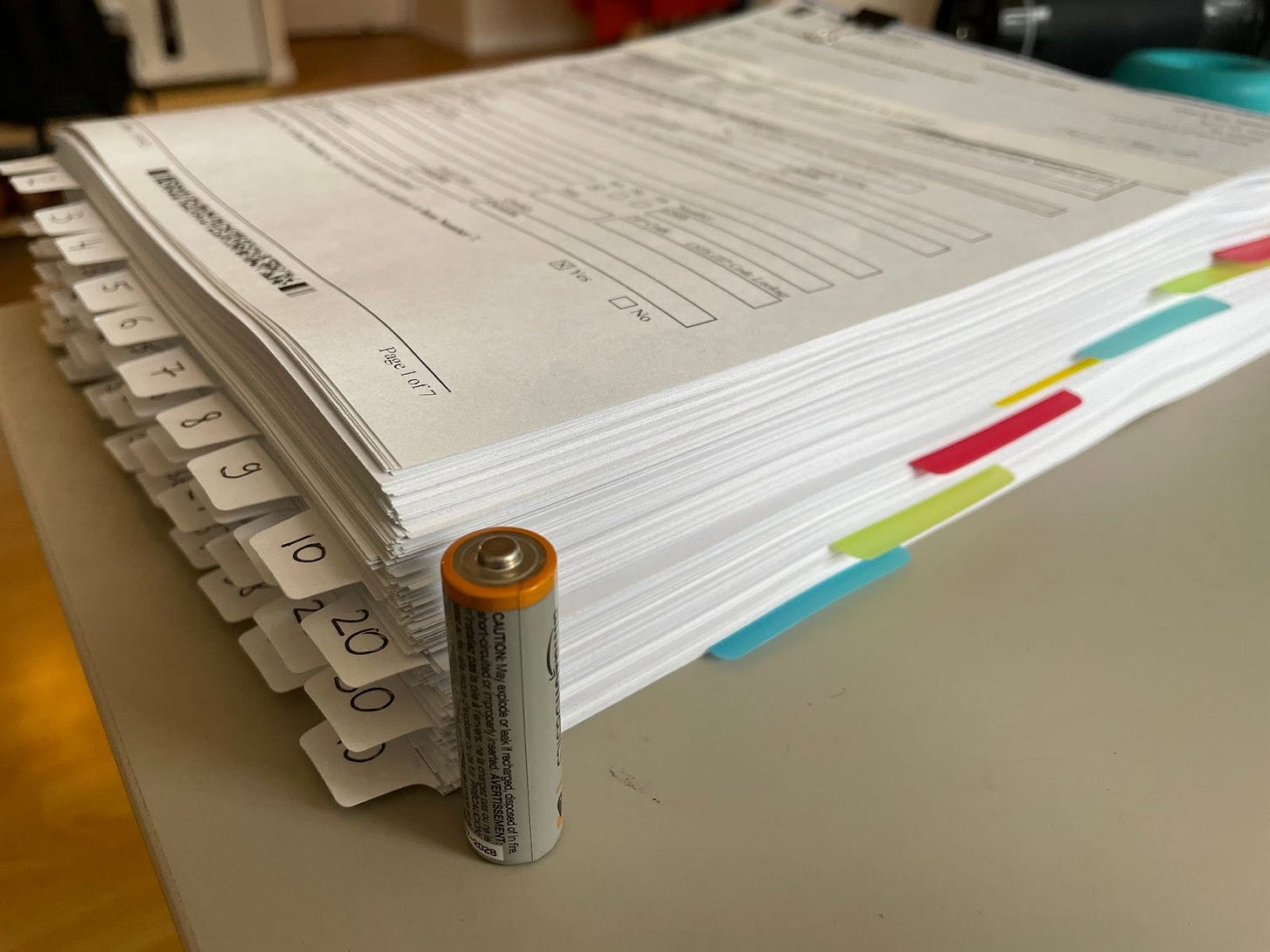

Although I have single-handedly put together an application of over 700 pages without any help from lawyers, I do not recommend trying to immigrate without legal advice. For once, few people have the time and ability to understand all the legal requirements themselves. More importantly, always keep in mind the survivorship bias: just because I was able to do it, it doesn’t mean that it can easily be done. Many people smarter than me have attempted to self-file and failed. If you are not in a place to gamble, I recommend that you seek advice from a good lawyer.

I am not interested in offering coaching, feedback, advice, or any other form of immigration support. I would like to help, but my time is limited, and I have to say “no”. At the end of the article, in the resources section, you will find a list of Slack and Discord communities where you may get help and/or a list of attorneys and consultants who may be of help. Once again, I will decline any requests to help with the immigration paperwork.

Although it may appear that replicating my path is “easy”, the EB1A Extraordinary Ability immigration category is arguably the hardest and the most prestigious. The intent of this visa is to bring to the United States people who have risen to the very top of their field, hence why the selection criteria are incredibly rigorous and notoriously hard (but not impossible) to meet.

The US has recently announced restrictions that apply to people with experience in offensive security. Again, I am not an advisor so take it with a grain of salt, but it appears that people who worked in offensive security companies such as NSO, Candiru, and the like, may have a hard time obtaining a US visa. It is entirely possible that I am misreading this, so please talk to your advisor if this applies to you.

The intended audience of this article is people who work in the cybersecurity field, regardless of their profession - product managers, security engineers, business development leaders, incident responders, startup founders, and the like.

My story: a brief take

Many years ago, I read this quote attributed (probably erroneously) to Thomas Jefferson: “I'm a great believer in luck, and I find the harder I work the luckier I get”.

I have always seen my life as a strong example that hard work pays off, and that the best way to succeed is to outpersist those around me. Having been raised in an Eastern European orphanage, I started my own business at the age of 19, ran an international charitable foundation helping orphaned kids at the age of 20, and came to Canada at the age of 22 without speaking a word of English. After quickly learning the language, I found myself working in the tech industry and chose to focus on product management. I grew from a product owner into a head of product in a California-based cybersecurity startup, and a few years after deciding to focus on cybersecurity, I was recognized as a renowned product leader, and this blog, Venture in Security, became one of the most prominent sources about the business side of cybersecurity.

All this is a long way of saying that I do not believe nor endorse anyone trying to look for shortcuts or game the system. There are firms that offer “simple and easy” ways to get the green card, but demonstrating that the applicant has attained the very top of their field is anything but “simple and easy”. And yet, I am a living example that it can be done.

When I started to work on my EB1A application, I realized that there was little extra I needed to do to meet the requirements of this esteemed visa category. For many years, I have been publishing articles on TechCrunch, Venture Beat, Dark Reading, and Hacker Noon, to name a few. Since 2016, I have been invited to judge many local and global hackathons, and since 2021, I have been helping VC firms evaluate cybersecurity startups. Moreover, I have been advising cybersecurity startups about product management, product-led growth, and go-to-market strategy, mentoring emerging entrepreneurs in accelerators, and leading many impactful industry-wide initiatives. My EB1A application was over 700 pages in total, 28 of which were the cover letter alone. The truth is that although the bar for the EB1A visa is high, I do believe that many people active in cybersecurity around the world are already doing things that could qualify them to immigrate to the United States. Many run successful startups, some do open source projects on the side that have been widely adopted around the world, others build tools, present at Black Hat and DEF CON, organize BSides, etc. I have met many extraordinary individuals working in cybersecurity, and I hope this guide will enable them to start the process if that is something they are interested in.

Understanding the US approach to immigration

Over the years, I have observed many people, including those in my immediate network, struggle with US immigration. Year after year, I hear stories about those who are being sent back to the country they were born in, even though the only place they’ve called home for decades is the United States. I have seen Harvard alumni, talented software engineers, creative artists, hardworking farmers, and others put in circumstances where they have no choice but to leave everything they’ve built and leave the US.

Many of these stories are truly touching, and when we hear about them in the context of human lives, words that often come to mind are “unfair” and “unjust”. I am not here to talk about how bad (or great) the US immigration system is. Instead, I would like to share my subjective view of the US approach to immigration.

The biggest mistake I see people make is thinking that immigration is about allowing people to move around and live where they want, building their lives, and working hard to contribute to the country they choose to call home. While it may sound cold and disheartening, immigration isn’t at all about good intentions and allowing people to achieve their dreams; its intent is much more pragmatic.

In order for the United States to remain the leading world power, it needs to continue growing. The policymakers understand that quite well, and it is this understanding that drives decisions about immigration. There was a time when to grow, the country needed more hands - dedicated, loyal, ambitious people willing to put in the hard work required to build the critical infrastructure - roads, dams, and power stations. The knowledge-based economy we live in today needs different ingredients for growth, namely capital and talent.

If one were to step back from the multitude of distinct immigration programs available today and take a systems view, it is easy to see that at the core, there are three visa streams:

Immigration programs that require capital (investment) to attract high-net-worth individuals

Immigration programs that require talent to attract extraordinary talent

All other programs for good people interested in living in the United States permanently

Although it may sound unfair to put refugees, diversity visa applicants, postgraduate study permits, H1B, and other work permit holders all into one bucket, I will explain why I do it.

It all comes down to the ease of immigration and the level of certainty the process will be successful. The United States needs exceptionally talented people, hence why it created the EB1A program which makes it easy and quick for anyone who can reach the high bar of the requirements, to move to the US. The same applies to high-net-worth individuals coming to invest in the US economy. Both categories of immigrants are highly desired, and the government tries its best to attract these people to the US. For anyone else, life is a lottery - whether we’re talking about refugees, H1B applicants, diversity visa applicants, etc.

I have concluded that instead of leaving their destiny up to chance or trying to fight the way immigration works, people who are driven, motivated, and hard-working, can position themselves for one of the two paths that work, namely investment or extraordinary talent. While not everyone can make millions of dollars over the course of a few years, many can rise to the very top of their profession and qualify for the EB1A visa.

Overview of the EB1A Extraordinary Ability Visa category

EB1A is a first preference immigrant visa the intent of which is to enable extraordinary individuals who have achieved the pinnacle of their field and received national and international acclaim, to remain permanently in the United States and work in the field they excel at. Commonly known as the “Einstein visa” or “talent visa”, it is exclusively available to those who can prove that they have risen to the very top of their profession.

The EB1A visa has several advantages over other types of immigrant programs:

Although it is considered an employment-based visa, it does not require a company to sponsor the applicant. For instance, I applied on my own, without company sponsorship. The applicant does not need anyone to prove that the company couldn’t find a qualified American resident for the role (known as PERM certification) or even a pre-arranged job offer.

One of the conditions of the EB1A immigrant visa is that after moving to the United States, the applicant will work in their field of endeavor, or to put it simply - in the same field where they attained national or international acclaim. For example, if a person applies as the top chemical scientist, he or she must be coming to work in the field of chemical sciences. This does not, however, mean that they must work for the same employer (in fact, they can be coming to the US without having any employment pre-arranged).

There is no limit on the number of EB1A visas that may be issued during the year. Moreover, the priority date for EB1A visas is always current, which means that as soon as the immigrant petition is approved, the applicant can apply for a green card. This is especially critical for people born in countries with long wait times such as China and India. While it can take decades for Indian or Chinese nationals to immigrate under other programs, the EB1A category makes it possible for them to receive a green card in a year or two.

EB1A is one of the visa categories eligible for premium processing. This means that for an extra $2,500 an applicant can receive the response about their application within as little as 15 calendar days. Moreover, there is no limit to the number of times a person can apply for this visa. It is possible to re-apply at any time after receiving a rejection and strengthening the application package.

There are several potential outcomes when you apply: approval, request for evidence (RFE), and notice of intent to deny (NOID). Another one involves investigations of fraud but I am going to assume that this isn’t something you plan on doing (don’t). The RFE & NOID mean that even when immigration officers are unsure if you meet the requirements of the visa, or if they think you don’t, you will be given a chance to prove it to them before they make a final decision. This is a great opportunity to clarify and strengthen the application, instead of seeing it get denied without your chance to address the concerns USCIS may have. RFEs are very common for EB1A applications; about 50% may get an RFE. The good news is that you will get a detailed explanation of what is missing and a timeframe to submit your response to the RFE.

Requirements of the EB1A Extraordinary Ability category

Given all the advantages of the EB1A immigrant visa program, it may not come as a surprise that the bar for receiving the approval is high. The USCIS officials heavily scrutinize every application, making it notoriously hard to obtain approval.

As USCIS explains, the applicant “must meet at least 3 of the 10 criteria below, or provide evidence of a one-time achievement (i.e., Pulitzer, Oscar, Olympic Medal) as well as evidence showing that you will be continuing to work in the area of your expertise. No offer of employment or labor certification is required.

To demonstrate you have sustained national or international acclaim and that your achievements have been recognized in your field of expertise, you must either include evidence of a one-time achievement (major internationally-recognized award) or 3 of the 10 listed criteria below (or comparable evidence if any of the criteria do not readily apply):

Evidence of receipt of lesser nationally or internationally recognized prizes or awards for excellence

Evidence of your membership in associations in the field which demand outstanding achievement of their members

Evidence of published material about you in professional or major trade publications or other major media

Evidence that you have been asked to judge the work of others, either individually or on a panel

Evidence of your original scientific, scholarly, artistic, athletic, or business-related contributions of major significance to the field

Evidence of your authorship of scholarly articles in professional or major trade publications or other major media

Evidence that your work has been displayed at artistic exhibitions or showcases

Evidence of your performance of a leading or critical role in distinguished organizations

Evidence that you command a high salary or other significantly high remuneration compared to others in the field

Evidence of your commercial successes in the performing arts”

As it is most definitely obvious, not all the criteria will be relevant to people working in cybersecurity. The intent isn’t to check as many boxes as possible but to provide strong evidence for at least three relevant criteria.

The evaluation is done in a two-step process. First, the USCIS official must establish if the person has received a one-time lifetime achievement, or has met at least three out of ten criteria. If the first step is successful, the immigration officer will conduct what is known as “merits determination”.

Meeting several of the criteria successfully may or may not mean that the person has risen to the top of their field and sustained national or international acclaim while doing so. For example, a person may have been receiving a high salary, published several articles in recognized media, and had a few interviews about their work without necessarily being at the top of their industry. This is where the merits determination comes in. During this step, the immigration official takes into consideration all the evidence provided in the application to determine how likely it is that the applicant hasn't just met some of the listed criteria, but is one of the very few who have risen to the top 1-2% of their profession. Needless to say, this part is quite subjective.

Common misconceptions about the EB1A Extraordinary Ability visa category

The EB1A immigration category is regarded as one of the most exclusive and hard-to-reach programs globally. People who immigrate under this program include Nobel Prize, Olympic Gold Medals and Oscar winners, world-renowned scientists, and others. Because of the veil of mystery and exclusivity, the Extraordinary Ability immigration category is surrounded by many misconceptions. In this section, I would like to address some of them.

The EB1A Extraordinary Ability visa category is only available to PhD holders

Although many of the people applying for the EB1A immigrant visa are indeed scientists and researchers, this is by no means a requirement. This immigrant category is open to anyone who has risen to the very top of their field of endeavor, including founders, cybersecurity engineers, incident responders, project and product managers, sales engineers, and others.

Some of the criteria for EB1A immigrant visas may look like they are only applicable to researchers, but it’s important to look beyond the obvious, understand the intent, and think about how they could apply to industry professionals. If someone is applying as a top scientist, they would likely need to have a PhD, but a top artist, a top football player, a top cybersecurity practitioner, etc. will need to show proof that applies to their area of expertise, and in most cases, it has nothing to do with a graduate degree.

You need to be a Nobel Prize winner

Although the EB1A visa has a very high bar, the Nobel Prize, Olympic Gold Medal, and Oscar winners are not an accurate representation of the vast majority of people who get the visa each year. For example, the "Evidence that you have been asked to judge the work of others..." criterion is often fulfilled by FAANG engineers by judging a certain number of hackathons. Many judges at these hackathons are there specifically to fulfill this criterion.

You need to have deep legal expertise to apply for EB1A or hire an attorney

Although I have built the case, written all arguments, filled out the application, prepared all documentation, and received approval entirely on my own, based on the strength of my profile, I am not here to argue that anyone can do it without legal help. Most people are better off hiring an attorney instead of spending time reading hundreds of documents, trying to understand all the nuances of the process, and figuring out ways to put together a detailed legal argument.

Having said that, my conclusion is that putting together a successful EB1A application is not about constructing a legal argument and citing laws and regulations. It is about explaining in plain language how and why an applicant meets the criteria defined in regulations.

You can simply put together a strong case without any help at all

Although I did not hire an attorney, I did spend time and effort to carefully study hundreds of pages explaining how to successfully build the EB1A case.

At the end of this article, I will share a list of resources I studied that enabled me to submit the application and have it approved in under two weeks. In total, I paid under $120 to access all these materials and build an understanding of what I need to do. Needless to say, there is no way I would have been able to succeed without doing all this work. Regardless if you are looking to work on your own, or if you will be seeking help from a legal counsel, you will need someone to learn from.

Building a case for the EB1A Extraordinary Ability visa category for people working in cybersecurity

Determining the “field of endeavor”

The first step in preparing the application for an EB1A Extraordinary Ability immigrant visa is to define your area of endeavor, or in other words - the professional field you will be applying under. Since the goal of your application is to demonstrate that you possess exceptional talent and have risen to the very top of your specific field, you need to make sure to define it in a way that gives you an edge.

Typically, a well-defined field of endeavor consists of two parts - an occupation (product manager, sales engineer, business development professional, solutions engineer, incident response professional, etc.) and a field (such as cybersecurity). Examples include cybersecurity product managers, cybersecurity sales engineers, security engineers, cybersecurity detection engineers, security architects, and similar.

It is hard to overestimate the degree to which defining the most applicable field of endeavor can impact the success of the application. You want it to be:

Explainable - a person with no background in your field should be able to understand what you do. This does not mean that you have to dumb down your profession. Instead, you want to find a way to explain what you do and communicate the significance of your work without relying on technical jargon. For example, you can say that as a cybersecurity threat hunter, you work to proactively identify attackers that have not been caught through real-time detection tools organizations have purchased from security vendors.

Specific - it is nearly impossible to prove that you're the world's top engineer but it is much easier to explain what makes you a top Azure cloud security engineer. The more specific you can get without getting ridiculous, the better it is. One of the most common ways to narrow down your field of endeavor is to show your specialization. Note that the definition of specialization will vary depending on your role: for business roles, you can use industry domains (data security product manager vs product manager), while for technical roles, you can, for instance, use the technology (Node.js software developer vs software developer).

It’s worth noting that you should not be looking to make an argument that there is a talent shortage and that people with your expertise are hard to find. There are two reasons for this. First, it is not relevant to the application (remember, your goal is to show that you are on top of your field, not that you possess rare skills). Second, if you make an argument that your occupation is “rare”, immigration officers may suggest that you should apply under a different immigration category and go through a labor market assessment to validate that.

The criteria relevant to people working in cybersecurity

To my knowledge, there isn’t a cyber-focused award recognized globally at the level of Oscar, Nobel Prize, Emmy Award, Fields Medal, or Olympics medal. This means that most (if not all) people working in cybersecurity will need to provide evidence of at least 3 of the 10 criteria provided by the USCIS. Not all of the ten will be relevant either, realistically leaving the following eight:

Evidence of receipt of lesser nationally or internationally recognized prizes or awards for excellence

Evidence of your membership in associations in the field which demand outstanding achievement of their members

Evidence of published material about you in professional or major trade publications or other major media

Evidence that you have been asked to judge the work of others, either individually or on a panel

Evidence of your original scientific, scholarly, artistic, athletic, or business-related contributions of major significance to the field

Evidence of your authorship of scholarly articles in professional or major trade publications or other major media

Evidence of your performance of a leading or critical role in distinguished organizations

Evidence that you command a high salary or other significantly high remuneration in relation to others in the field

In the section that follows, I offer brief notes about evidence that could be used to satisfy these criteria. It’s worth noting that while the application only requires meeting three criteria, the immigration officer will need to be convinced that your application as a whole shows that you have risen to the very top of the field, and for that it can be very useful to meet more than three, assuming you have a strong evidence to provide. To remind you, this is my opinion only and not immigration advice. There is absolutely no guarantee that following these guidelines will get your application approved.

Satisfying each of the relevant EB1A criteria: notes and ideas

Evidence of receipt of lesser nationally or internationally recognized prizes or awards for excellence

There are multiple ways to define an “award”. First and foremost, these include the actual awards, for instance:

And many others

However, startup founders for instance may argue that receiving VC funding or getting accepted into a prestigious accelerator also constitutes an award.

To craft a compelling story, the cover letter may include the following:

Explanation of the nature of the award and its criteria which, ideally, should include some degree of high achievement

Information that shows exclusivity and significance - what percentage of the people who are nominated get the award, what are some of the examples of the people who received it in the past

Information about the judges, their qualifications, and what makes them qualified to evaluate excellence in their field

The perception of the award in the industry (articles about the prestige, press releases people and companies issue when the award is received which shows its importance, and similar)

Here are a few things to keep in mind about awards:

The recipient has to be the applicant, not their company or any other organization they are affiliated with

You cannot use the pay-to-play recognition we see in the industry where 100% of the people who apply, get the award (how does getting an “award” anyone can get for $1,000 show any degree of impressive achievement?)

The type of evidence and arguments will be highly contextual and dependent on each case. A cybersecurity startup founder who raised a seed round for his startup from Sequoia, for example, may show the evidence that they were pitching to the VC, that the VC did active due diligence, evidence that they received funding, a letter from Sequoia explaining how many companies they evaluate and what percentage of them get investments, articles showing that Sequoia is a prestigious VC and being funded by it is perceived highly favorably, information about VC’s portfolio companies that made a dent in the tech industry, etc. In short, you will want to explain what it is about being funded by Sequoia that constitutes an achievement, and back all of your statements with hard evidence.

Evidence of your membership in associations in the field which demand outstanding achievement of their members

This criterion intends to show that you were invited to join a highly selective membership organization that only admits people who have attained the very top of their field. For a membership to meet the high bar established by the USCIS,

The standard for admission to the organization must be highly selective

The membership must be in an association that requires outstanding achievements as an essential condition to become a member

The organization must be related to the applicant’s field of endeavor

The applicant must have been admitted to the association based on their outstanding achievements as judged by recognized national or international experts in their disciplines

The membership cannot be based solely on a level of education or years of experience in a particular field

The membership requirements cannot be based on employment or activity in an area (think professional designations), based on test scores, based on GPA, or based on payment of dues

For anyone working in the cybersecurity field, this criterion is probably one of the hardest to meet because there aren’t any organizations focused on cyber that clearly meet these requirements (at least, none I know of). There are, however, some other organizations which, if argued well, may or may not be accepted by the USCIS, including:

Y Combinator (potentially relevant to cybersecurity startup founders)

Techstars (potentially relevant to cybersecurity startup founders)

Entrepreneur First (potentially relevant to cybersecurity startup founders)

Antler (potentially relevant to cybersecurity startup founders)

Forbes Councils (potentially relevant to cybersecurity startup founders and executives)

I am sure there are more, but since I am not a security practitioner, I don’t know which organizations in the field (except those offering certifications that as we’ve established, do not qualify) would meet the criteria. I would imagine some Fellowships by think tanks and universities, cyber defense advisory council roles by the governments, and the like would work, but not sure what beyond that.

As a part of the evidence, you will want to provide:

Proof that you are a member (acceptance email, a letter from the association, etc.)

Proof that the association is highly exclusive and that you were able to join because of your extraordinary contributions (a letter from the association, a printout of the membership criteria from the website or the by-laws, etc.)

Proof that your acceptance was judged by recognized national or international experts in your discipline (letters from the organization stating who was on the selection committee, information about the people and their professional profiles which establishes them as well-regarded experts, etc.)

Evidence that other members of the organization are highly established, nationally or internationally recognized experts in their field, which establishes that since you’re also a part of it, you must be an extraordinary individual in your professional area

It’s important to keep in mind the intent of this criterion: to show that you are a member of a highly selective group you were invited to join because of your extraordinary achievements. It must either be an invite-only association, or something where many people apply but very few can get in - an accelerator, a community, an advisory board to a large government organization, a selective fellowship relevant to your field of endeavor, etc. For instance, if you are a member of the selection committee of a prestigious conference such as RSAC or Black Hat, and you can prove that many people applied and/or were considered for that role, but only 1-5% of them got it, this could very well be argued to be a “membership in an association in the field which demands outstanding achievement of its members”.

Evidence of published material about you in professional or major trade publications or other major media

This criterion intends to show that your work is highly regarded in your field, and therefore authoritative media relevant to your industry are willing to talk about it. This means a few things:

Immigration officers are looking for media coverage, not social media posts and the like. This means that if Dark Reading wrote an article about you building a startup to solve an important problem in the industry, that’s awesome, but if someone tweeted about it, or if you were invited to speak about it on a podcast run by someone in the community, it probably won’t work.

The media coverage has to specifically talk about you & your contributions. This means that an article about you discovering a zero-day vulnerability can be a great fit to satisfy this criterion, but an interview about your company that mentions your name in passing won’t be seen as strong evidence of your contribution.

The definition of “professional or major trade publications” basically means that the media that highlights your work can either be generic but with a large following (think Forbes, Wired, etc.) or smaller but well-known and authoritative in your domain (think The Hacker News, CSO Online, or IT Security Guru).

You will need to explain and provide evidence that:

Your work has been covered by the media (online or offline). This one is straightforward - think printouts and screenshots of the coverage with your name and discussion of your work highlighted.

The media is authoritative in your field and has a strong following. This may include printouts of visitor stats from SimilarWeb, relevant pages from the media “Advertise with Us” page or similar which provide information about its readership (think of this Dark Reading example), mentions of the media as one of the recognized sources to learn about your area of cybersecurity, etc.

Other evidence that shows that this is an impressive achievement. Did the same journalist previously interview a Head of Security from a large company? You can provide evidence of it and argue that they view your contributions as they do the work of this other significant person. Did 50,000 people read this article about your work? Did a famous industry leader comment on it or write a response to your interview? These are just some examples - look at your profile, think about what can act as proof that your work is being regarded as innovative and important, and bring attention to these areas.

You will want to have a few instances of media coverage, ideally in authoritative journals and magazines that people in your field read. This will, as always, be different depending on your particular situation: if you are a threat researcher, The Hacker News will be more relevant than TechCrunch, but if you are a startup founder, it’s likely (but not necessarily!) vice versa.

Evidence that you have been asked to judge the work of others, either individually or on a panel

As with all other criteria, this requirement is self-explanatory, and therefore the ways it can be met will highly depend on the context. The idea is that you have risen to the top of your field, and your contributions have been recognized by others so much that they ask you to judge the quality of work of your peers.

Some of the ways in which this criterion could be met include:

Reviewing CFPs (calls for papers) for security conferences. If you sit on the panel to review CFPs for, say, RSAC, Blue Team Con, Black Hat, or even for your local BSides, you can use this to show how you judged the work of others. You will want to provide the evidence that it actually happened (think email correspondence, scoring sheets, etc. which show that you evaluated the proposed submission and provided your expert judgment), pictures, and letters from the organizers explaining that it’s because of your extraordinary work in the industry that you were invited to review CFPs, information about the conference which shows its significance (number of attendees, famous people who presented or did a keynote before, prominent sponsors, etc). As always, keep in mind the intent: show that you did the work, and provide material evidence that proves that it matters. Because it has to be the work of your peers, student-focused events won’t qualify (it’s smart to include evidence showing what the typical attendees are).

Judging tech and cybersecurity-focused hackathons, capture the flag (CTF) competitions, and the like. Similar to the situation with conferences, you will want to provide the evidence that it actually happened (think email correspondence, scoring sheets, etc. which show that you evaluated the teams and provided your expert judgment), pictures, letters from the organizers explaining that it’s because of your extraordinary work in the industry that you were invited to review the CTFs, information about the CTF which shows its significance (number of attendees, famous people who participated or participated as judges before, prominent sponsors, etc). As always, keep in mind the intent: show that you did the work, and provide material evidence that proves that it matters. Because you need to judge the work of your peers, student-focused events won’t qualify.

Providing expert judgment about startups and what cybersecurity founders are building. This is one of the more creative ways to potentially meet the “judging” criteria - by showing that you have attained industry-wide recognition of your expertise, and therefore you have VC firms reaching out to you and asking to provide your assessment of other startups and help them decide if they should invest. Many cybersecurity startup founders and leaders of large companies have well-established relationships with venture capital firms and routinely do this as a favor. You will want to provide the evidence that it actually happened (think email correspondence with the VC that shows that you were asked to evaluate a company and you completed this evaluation), letters of support from VCs explaining that it’s because of your extraordinary work in the industry and expertise that you were invited to review their potential investments, information about the VC firm, its work, partners, and portfolio companies, and an explanation of the significance of your assessment (based on your judgment, a VC firm may or may not allocate millions of dollars to the company - what can be more significant than that?). As always, keep in mind the intent: show that you did the work, and provide material evidence that proves that it matters.

Evidence of your original scientific, scholarly, artistic, athletic, or business-related contributions of major significance to the field

This is one of the most mystic EB1A criteria, especially for those working in the cybersecurity space, and yet it is also one that many people can meet if they are truly on top of their field. Here are some examples:

If you are a security engineer who started or maintains a popular open source project used by security teams in different countries, you could potentially meet this criterion. You will want to provide evidence of your work along with the proof of impact your project achieved. This could be stats about usage, the list of companies who leverage your tool, and letters from these companies explaining how your open source project helps them to secure their infrastructure, cut costs, etc.

If you are a detection engineer who contributes to open source detections used by security teams in different countries, you could potentially meet this criterion. You will want to provide evidence of your work along with the proof of impact your detections achieved. This could be stats about usage, the list of companies that leverage your detection content, letters from these companies explaining how your detections helped them prevent or discover cyber incidents, testimonials from experts in the industry talking about the significance of your work for cyber defense, etc.

If you are a security researcher who discovered a new way to identify a threat, did several talks at security conferences, published a research paper, etc., you could potentially meet this criterion. You will want to provide evidence of your work along with the proof of impact your research achieved. This could be information about the significance of the threat you discovered, the types of companies that would have been affected by your discovery, letters from vendors, security experts, and conference organizers explaining how your work helped them detect, prevent, or remediate cyber incidents, testimonials from experts in the industry talking about the significance of your work for cyber defense, etc.

If you are a startup founder building a cybersecurity company, you could potentially meet this criterion. You will want to provide evidence of your work along with the proof of impact your company achieved. This could be information about significance of the problem your company is solving, media coverage, proof that you received recognition from the government, VC funding, analyst mentions, etc., information about the types of companies that find your company’s offerings valuable, list of customers, customer testimonials about the impact your company’s solutions had on their business, talks you did on security conferences, letters from conference organizers, testimonials from experts in the industry talking about significance of your work for cyber defense, etc. Another cybersecurity product manager I know, for example, used four US patents she wrote and submitted proofs of 2 of them implemented in security products that are being used now by Fortune 500 companies. She brought the US patent number (and the PDFs), with letters from CEOs/C-level who also mentioned it, and articles stating the company is now using the product.

The bottom line is this: to provide evidence of your original contribution to the field, you need to show in very practical terms how you made the industry better. What constitutes an original contribution is highly contextual and dependent on your role, the work you do, and so on. I think people who are driven, active in their industry, visible, and proactive in doing some projects on the side related to their work, often accumulate more than enough evidence to show their impact on the field.

Evidence of your authorship of scholarly articles in professional or major trade publications or other major media

Although the requirement states “scholarly articles”, in the context of industry professionals, this means articles that showcase one’s expertise in their field. To satisfy this criterion, you will need to provide a proof that:

In your field, publishing articles is not something everyone does but a sign that your expertise is highly valued

Your expert contributions, thought leadership, and analysis related to your field of endeavor were published in the media

The media they were published in can be considered “major” as evidenced by their readership, reputation in the field, and international distribution

First of all, you will need to explain that unlike in fields such as academic research, in your area of endeavor, it is rare for someone to publish articles and become a thought leader in the industry. This should establish that people in your profession who do get their insights featured in leading media are evidently in the very small percentage, which demonstrates both the extraordinary ability and the recognition of this ability globally.

To prove the second part, you will need to provide printouts/copies of your publications (the first two pages are enough). It’s important that your name is listed as the author (co-author), and so are the title and the date the article was published.

You will then need to provide evidence that the media is authoritative in your field and has a strong following. This should explain the nature of the media and may include printouts of visitor stats from SimilarWeb, relevant pages from the media “Advertise with Us” page or similar which provide information about its readership (think of this Dark Reading example), mentions of the media as one of the recognized sources to learn about your area of cybersecurity, etc. SimilarWeb is a fantastic source to show what countries readers come from, which will enable you to argue that your work receives international recognition. Explaining the criteria to get published in the media (ideally, it should be a highly selective media such as TechCrunch) and showing what other experts have had their thought leadership showcased on the same media can further help to build a convincing picture. For printed media, it’s equally important to show the information about distribution and readership.

All the statements made in the cover letter should be illustrated by the material evidence provided in the exhibits.

Many people working in cybersecurity, especially startup founders and executives, are likely to have already accumulated a long list of publications in industry media establishing them as experts. Those who haven’t, as long as they truly have unique perspectives and great insight, can always do it. Many media have unpaid contributor programs allowing industry experts to publish their insights, including:

None of these will accept vendor-focused pitches, ChatGPT-generated trash, listicles, and other low-quality content. But, if you have something of value to offer, I am confident you can get them to publish your insights. Keep in mind it can take a few weeks, and in some cases, over a month, to hear back after you reach out to these media.

Evidence of your performance of a leading or critical role in distinguished organizations

To satisfy this criterion, you will need to prove two things:

That you have played a leading or critical role in an organization, and

That the organization where you played a leading or critical role meets the criteria of being “distinguished”

Let’s start with the second part. There is a misconception that only people who work for Google, Meta, CrowdStrike, Harvard, or some other prominent institution, can meet this criterion because “distinguished” means “instantly recognizable”. That is entirely untrue because what defines an organization as distinguished is highly contextual. In practical terms, here are the examples of the evidence that can help establish the company you work for as distinguished:

Your organization serves large or recognizable customers. If public companies, government institutions, organizations with large numbers of employees and global presence, organizations with critical impact on the infrastructure, or organizations valued as “unicorns” after raising large amounts of venture funding choose to use your product, this can be a great argument that you work at a reputable institution. Evidence could include screenshots of customer testimonials, printouts of the marketing materials, letters from the customers themselves, as well as media coverage and other information that shows that your product is being used.

The products your organization builds are used by large numbers of customers, or if it’s open source - receive a large number of stars and have many contributors.

Your organization received venture funding from prominent VC firms. By showing the media coverage, explaining the criteria, and highlighting the strong sides of the VC firm that invested in your company, you can also make an argument that your organization is reputable.

Provide evidence that your organization received media coverage in reputable newspapers, has an active presence at important industry events such as RSAC, Black Hat, Gartner Summits, BSides, etc., was featured in books, analyst reports, received awards and recognition, etc.

Keep the intent in mind: since your situation is likely to be unique, think about what can prove that your organization is reputable, and use that as an argument backed by material evidence.

After providing and explaining the evidence that the organization you work at meets the criteria of being “distinguished”, you will need to argue that the role you played can be considered leading or critical. In a nutshell, you should tell a story explaining what you did, what impact it had on the organization, and how your contributions made an extraordinary difference. The intent of this criterion isn’t to show that you have a leadership title but to validate that you have made an incredible impact.

If there are articles, reports, or other information you can share that provides context and explains how you meet this criterion, that’s great; reference letters written by senior leaders from your organization could work as well. By references, I mean in-depth, 3-5 pages-long letters that establish the context about the person providing the reference, the organization, and your role in it, and describe in great detail the work you did that made you play a leading and/or critical role, the impact of this work, and what separates it from the ordinary performance of responsibilities of a job.

Ideally, you want to find a way to quantify your impact and make it possible for someone who isn’t an expert in your domain to understand what you did and how your contributions impacted the trajectory of the organization. You should be looking for at least two to three impactful initiatives, preferably from several organizations you’ve been a part of.

Evidence that you command a high salary or other significantly high remuneration in relation to others in the field

The high salary criterion is the most straightforward to prove: your total compensation should be significantly higher compared to that of your peers with the same level of experience in the same region and the same occupation. To meet this requirement, you need to establish a few things:

What is your total compensation

What is the compensation of others in your professional field with the same tenure in your area

How your compensation compares to that of others

First, you need to provide proof of your compensation. The following are some of the documents you may want to include:

Pay stubs

Tax assessments from previous years

Bank statements showing the money deposited in your account

A letter from your employer showing your total compensation

Note that benefits such as healthcare insurance etc. are not included in this calculation. If you are a startup founder or an employee in an early-stage company and a large part of your compensation consists of equity, you may need to provide evidence that this equity is worth something. For example, you could show:

Documents that establish the number of shares you own

Documents that establish the total number of shares issued by the company, and subsequently - the percentage of your equity ownership

Information that establishes the value of the company (media coverage showing the company valuation from the previous priced rounds, etc.)

Calculation of the value of your compensation (equity % x company valuation, etc.)

References from the Department of Labor website such as this or this

Explanation that it is common for tech startups to compensate their employees by offering equity in place of cash

Here is what USCIS says about equity in the context of another visa category, O1: “If the petitioner demonstrates that receipt of a high salary is not readily applicable to the beneficiary’s position as an entrepreneur, the petitioner might present evidence that the beneficiary’s highly valued equity holdings in the startup are of comparable significance to the high salary criterion”.

To establish what salary is common for people in your role, you will want to look for salary surveys from recruiting firms, market data, government sources (Department of Labor website), as well as sites (or their equivalents in your region) such as Glassdoor, Payscale, and Indeed. Your goal is to find reports showing the compensation for people in your role:

In your geographical area

With the same years of experience

In the same domain

Ideally - with the same educational and professional backgrounds

As with all other evidence, when summarizing it in your cover letter, you will want to provide a clear articulation of why you chose specific reports as a baseline, what makes them credible and accurate, and so on. Think of it as writing a university paper: when you are making a statement, you need to reference the source and provide a copy of this source in exhibits.

Lastly, you will need to explain how your total compensation compares to that of others. To succeed, your compensation should be in the top 90th-95th percentile in your field in your specific area. I cannot stress enough how critical it is to focus on your geographic region. If, say, you are a top earner in Ho Chi Minh City, your compensation will likely be lower compared to someone working in New York but that doesn’t matter: you just need to prove that you are making more than 95% of others in your field in Ho Chi Minh City.

Merits determination

There is a legal explanation of this but since I am not a lawyer, I will offer a simple and human-readable version.

USCIS takes a two-step approach to evaluating the EB1 Extraordinary Ability visa petition. First, it will analyze the application and count the number of criteria the applicant meets. This part is not all that controversial. If the petitioner submits evidence that meets at least three of the criteria, the immigration official will then review the application in its totality. This step is called “merits determination” and it is designed to determine if the applicant is one of the very small percentage of people who have risen to the very top of their field of endeavor, and whose extraordinary achievements were recognized by others in their field of expertise both nationally and internationally.

The merits determination step is where many applications fail. Think of it as security vs compliance I’ve talked about before: you can check the boxes and prove that you meet the required criteria (or get the auditor to say that you are “complaint”), but then you need to pass a real test where each of your arguments is being evaluated and scrutinized to see how altogether this shows that you meet the requirements of the EB1A visa (or that your organization is actually secure). And, similar to the security vs compliance debate,

If you do indeed have a strong profile that can be seen as extraordinary in your field, you should have little issues meeting individual criteria (think “secure is most likely compliant”)

The same isn’t true the other way around: just because you can check three of ten boxes, this doesn’t at all mean that you’ve risen to the top of your field (think “compliance does not mean security”).

You will want to address the merits determination step in your cover letter and explain how all the evidence provided, when evaluated together, proves that you are one of the very small percentage of people who have risen to the very top of their field of endeavor, and whose extraordinary achievements were recognized by others in their field of expertise both nationally and internationally. This is also a great place to provide the bits and pieces that aren’t strong enough to satisfy the individual criteria but are useful to strengthen the profile overall. For example, if you have one interview in Dark Reading, it may not be enough to strongly say that your work has been covered in major media, but it’s a great bonus to mention in the merits determination section.

Evidence that the applicant intends to work in the area of their extraordinary ability after moving to the United States

If you are sponsored by your employer, having a pre-arranged employment contract or a letter from your employer will help to check this box. You can, however, apply entirely on your own; you do not need to have a US employer sponsor, provide a job offer, or otherwise endorse your application, and you don’t even need to have a specific company in mind. It should be sufficient to state in the application that after moving to the United States, you intend to work in the area of your extraordinary ability.

How the applicant’s immigration can benefit the United States

Given the state of the industry, the ever-growing number of cyber breaches, the geopolitical situation, rising insurance premiums, and the frequency of large-scale data losses, I won’t spend time explaining how people with expertise in cybersecurity can benefit the United States. Without threat hunters, red, blue, and purple teamers, digital forensics and malware analysts, CISOs, OSINT investigators, detection engineers, and other security practitioners we cannot defend our digital world. Without security engineers and architects, it cannot be designed securely from the ground up. Without product managers, engineers, designers, and customer researchers it’s not possible to build the next generation of security tools. Without sales, business development, and partnerships professionals it’s impossible to get people to use the next generation of security products. This list can go on and on, and as someone who works in cybersecurity, you should have no issue satisfying this criterion.

Notes and lessons learned: building a successful EB1A application

A note about references

Here is an excerpt from the USCIS policy manual which talks about reference letters: “Many petitions to classify a person with extraordinary ability contain letters of endorsement. Letters of endorsement, while not without weight, should not form the cornerstone of a successful claim for this classification. Rather, the statements made by the witnesses should be corroborated by documentary evidence in the record. The letters should explain in specific terms why the witnesses believe the beneficiary to be of the caliber of a person with extraordinary ability. Letters that merely reiterate USCIS’ definitions relating to this classification or make general and expansive statements regarding the beneficiary and his or her accomplishments are generally not persuasive.

The relationship or affiliation between the beneficiary and the witness is also a factor the officer should consider when evaluating the significance of the witnesses’ statements. It is generally expected that one whose accomplishments have garnered sustained national or international acclaim would have received recognition for his or her accomplishments well beyond the circle of his or her personal and professional acquaintances.

In some cases, letters from others in the beneficiary’s field may merely make general assertions about the beneficiary, and at most, indicate that the beneficiary is a competent, respected figure within the field of endeavor, but the record lacks sufficient, concrete evidence supporting such statements. These letters should be considered, but do not necessarily show the beneficiary’s claimed extraordinary ability.”

Do not assume you can rely on reference letters alone to put together a successful EB1A application. They are most certainly useful, and any person who has genuinely done a lot to advance security space should be able to easily obtain endorsements from the industry. However, letters of reference won’t magically turn a weak application into a strong one.

When you do provide reference letters, keep in mind that many of them should be from experts and leaders in your field who have learned about you through the impact of your work on the industry, not those who have worked with you directly. Each letter should provide a brief overview of the background of the person providing the reference, explain how they got to know you and offer tangible, material evidence that your contributions made a solid impact on your field. This means that ideally, you want to see statements with numbers, stats, and other quantitative metrics showing the magnitude of your influence, and specific examples of your impact. It’s a good idea to also provide a resume or a printout of the LinkedIn page/biography of the person signing the recommendation that clearly establishes them as an expert in their field. The EB1A DIY package by Green Card Apply listed in Resources at the end of the article, provides some fantastic examples of reference letters for EB1A.

A note about the cover letter

A cover letter is the most important part of your application, and it is often the only part of the application that gets read (or so I heard). The cover letter needs to tell your story. It has to establish your background, what criteria you’re trying to tackle, explain how you meet them, provide information for merits determination, explain that you intend to work in the area of your extraordinary ability after moving to the United States, and convince the immigration officer that the US and its economy will benefit from your presence in the country. All the arguments of how you meet the criteria of the visa, references to the well-organized evidence, and the appendix of exhibits will go here. This is why the length of the cover letter for the EB1A application typically ranges from 10 to 25 pages (mine was 28 pages).

One kind of evidence can satisfy multiple criteria (and they should all tell a story)

Let’s say you were selected to be on the board of a very exclusive organization for people in your field, and as a part of that organization you are evaluating the work of others. Then, a prominent media person chooses to interview you about your contributions to the industry. This is an example of how membership, judging the work of others, and being featured in the major media can all work together.

One kind of evidence can satisfy multiple criteria (such as judging and membership), and all the evidence together has to tell a story. Remember that USCIS officers are people, and they only have 20-30 minutes to spend on your application. In this time, they need to understand your story - how what you have done puts you at the top of the industry, and how your work will greatly benefit the United States.

When I say that your application needs to tell a story, what I also mean is that all criteria you are tackling, and all the evidence provided for each, should all be in alignment, and tell the same story.

Build a strong application

Although you only need to meet 3 of 10 criteria, it’s a good idea to provide evidence and attempt to meet all criteria you are strong on. The chances that the officer will be satisfied that you met 3 of 6 criteria you provided the evidence for are higher than you meeting 3 of 3.

At the same time, remember that the bar is very high, so if you have some evidence for one of the criteria but you feel like it’s weak, it’s best to not try to meet that requirement. Instead, you can present that evidence for the merits part to strengthen your overall application.

Although theoretically, all criteria are equal and there is a regulation that prevents immigration officers from discriminating based on what criteria the evidence was provided for, remember that those evaluating your application are people. They are good logical thinkers, and as such they have their own assumptions and ideas you need to deal with. For example, while talking about “original contribution” and “media coverage” is optional, as are reference letters from the industry experts you haven’t worked with directly, it can be hard to argue that you’re on top of your field when you don’t have any evidence of either.

Presentation matters

Presentation of the application matters. First of all, only include the relevant evidence. Less is more, as your case will be judged on the quality of the arguments and the evidence provided, not quantity.

There is no need to include printouts of full articles you’ve written - the first two pages that show your name, date, and the title of the article should be more than enough. Since you will be submitting hundreds of pages, make sure to organize, label, and categorize all the evidence to make it easy to navigate (the USCIS provides some great instructions, and so does the EB1A DIY package by Green Card Apply I reference in the Resources section at the end). Highlight your names in the evidence documentation, as well as the things you want the officer to read/notice.

You will probably want to get help

Although I did all the work on my own - researching the nuances and understanding the EB1A requirements, collecting evidence, asking for reference letters, putting together legal arguments (28-page long cover letter), and filling out the application, I do not necessarily recommend doing it without legal counsel.

Talking to a qualified legal expert can save you a lot of time, money, and effort - from helping to understand if you can qualify for this type of visa, to strengthening your profile and preparing a successful application. Unfortunately, I do not have any lawyer recommendations (for obvious reasons), but you can find them in the Slack & Discord communities I provided in the Resources section at the end of this article.

Closing words: do honest work and do not look for shortcuts

Here are some of the things people interested in applying should keep in mind:

Immigration officers are smart people, and they see thousands of applications every year which means that even though they are not cybersecurity experts, they do have the necessary skills and experience to evaluate your candidacy. However, for them to do it effectively you will want to use terminology that explains to a non-domain expert what is it that you do, what is the significance of this work, and how your achievements put you in the top 1% in your field.

The EB1A application is not the time to be humble. The whole idea is that you are trying to convince someone that you are extraordinary, and the only way to do it is to own and be proud of your accomplishments.

Many of the applicants are scientists and researchers, and therefore immigration officials are used to seeing documents that list PhD from renowned universities, research papers, and citations. And yet, as an industry practitioner, you do not need to have any of this - your goal is to provide evidence relevant to your field.

Remember that the immigration officers reviewing your application are humans - humans who are emotional, subjective, and inquisitive. When preparing your application, try to look at it from the assessor’s lenses, think about how each statement you make can be perceived by someone who sees tens of similar documents daily, and how the person may feel after going through your paperwork. You want them to feel good about saying “yes” to you, and you want them to have confidence that they are doing good for the country (because they are).

However tempting this may be, do not think that ChatGPT can help you get together a strong application, and don’t try to game the system. If you choose to work on your application without any help from lawyers (I do not recommend doing this even though this is exactly the path I took myself), you will have to spend many hours and put in a lot of effort to make it successful. Do not try to look for shortcuts such as ChatGPT - not only it won’t help you, but it can also jeopardize your future immigration.

Good luck with your immigration journey! If you do end up moving to the US after reading this article, please get me a cup of peppermint tea when we meet at one of the security conferences (or somewhere else).

Resources

The following are some of the resources I found useful when working on my application. I am not affiliated with either, so please do your own research and consult with your attorney before using any of these or relying on them for advice.

EB1A DIY package by Green Card Apply

It would not be an overstatement to say that this affordable (just over $100) package was the most critical guide that enabled me to prepare my application and get it approved after the first attempt. I am not affiliated with Green Card Apply in any way, but I do highly recommend their work for anyone considering to self-file the EB1A application.

AAO Non-Precedent Decisions is a database of select applications denied by the USCIS. To understand what doesn’t work for the immigration officers, set the filters to “I-140 - Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker (Extraordinary Ability)” and use dates/terms to narrow down the search.

USCIS Tips for Filing Forms by Mail

Exactly what it says - tips for filing forms and organizing the application.

Brian Lisonbee, immigration lawyer, explained each of the ten EB1A criteria on his blog. I highly recommend this for anyone interested in self-filing the EB1A application.

A Slack community moderated by Aditi Paul where ~2,000 members collaborate, answer questions and help one another with preparing applications for EB1A. Please reach out to Aditi for an invitation directly.

A systematic guide to successfully apply for an O1 visa

Although the EB1A visa has a substantially higher bar than O1, many of the criteria and approaches are still relevant. I found this article by Sahar quite useful.

A Discord community started by Sahar, author of the article above, to demystify the application process and make it easier for eligible petitioners to gain their visa faster and cheaper.

O-1 Visa for Startup Founders Webinar

A webinar recording by LegalPad, an immigration law firm, about O1 Visa for startup founders.

O-1A Criteria for Startup Founders

Another article by LegalPad (remember the criteria for O1 visa are similar to that of EB1A)

How to Strengthen Your Employment-Based Green Card Profile

Some useful and practical advice for those trying to proactively work on fulfilling the EB1A criteria before attempting to apply for the visa.

US Immigration Law Offices of Chris M. Ingram EB1A Materials

This website offers several practical instructions for putting together the EB1A application which I found useful when working on my own case.

Although not a resource I needed to leverage personally, I would like to give a shoutout to Unshackled Ventures - a venture firm that sponsors visas, provides full immigration support, and a community of resources to their founders. Unshackled supports immigrant founders and helps them launch a company no matter their current work authorization - from student visas to being a new US citizen.

Great post I also used the AAO decisions alot. Might be good to checkout Immibadger https://www.immibadger.com it was quite helpful to go through the analysis and get feedback on the evidence before submitting my petition