You don’t start a platform, you earn the right to become one

Together with Shashwat Sehgal, we are looking at four stages of building a platform and what this means for founders and investors

In cybersecurity, “platform” is the most abused word, used by every startup with two engineers and a feature flag. We can’t blame founders, marketers, and VCs since that’s the expectation, and everyone has to do what’s expected. In this piece, Shashwat and I are arguing that no company starts as a platform; instead, startups earn the right to become a platform. Founders need to know which direction they’re headed because not all growth paths are equally likely to succeed. We are going to dive deep into different stages of building a platform, explain what are the “big rocks” of cyber, and what are some of the pitfalls founders should avoid.

Shashwat Sehgal is the CEO and co-founder of P0 Security, the first unified PAM/IGA platform for modern production environments, that governs, orchestrates, and secures all forms of access for all identities, without impeding the productivity of development teams. With previous stints and leadership roles in multiple tech enterprises such as Splunk and Cisco, Shashwat brings a depth of expertise in cloud security and enterprise software development.

Community announcement - BSidesNYC call for papers is still open.

In addition to amazing technical talks, BSidesNYC has a special 'Entrepreneur' track - a space for founders to share real stories and lessons from building security companies. If you're a founder, this is your chance. It’s rare to find a conference that mixes security/tech with honest startup experiences.

Three tracks are now accepting proposals:

> Technical Talks - Core conference content: red/blue team, privacy, policy, and more.

> Technical Workshops - Longer session of hands-on exercises.

> Entrepreneur Talks - Share what it's really like to build and scale a security company.

Four stages of building a platform

Every successful platform started as a point solution. This is true for Palo Alto, Okta, CrowdStrike, and any other large security player from the past, present, and the future.

Generally speaking, there are four stages of building a platform.

Stage 1: The one-trick pony that opens doors (Seed to Series A)

At the earliest stage, a startup earns attention by doing one thing extremely well - solving a specific problem for a specific persona. At this stage, two things happen: buyers who resonate with the problem are happy that there is a small, specific solution, while those that don’t, complain that the company is building another “one-trick pony”. Either way, it’s by being this one-trick pony that startups are able to get in the door. A just-in-time access control tool for developers, a fast vulnerability scanner for Kubernetes, or a solution to check firewall policies for PCI compliance, - all these have one thing in common: they are focused on one persona, one pain point, one job.

Stage 2: Expanding to adjacent use cases (Series B to Series E / growth stage)

Once the company reaches early growth, it starts to expand into adjacent use cases. They’re still solving problems for the same persona, but now they’re expanding horizontally, covering many adjacent problems. Think of Vanta going from SOC 2 to ISO to HIPAA, or Okta going from SSO to supporting basic identity workflows. The platform narrative starts to make sense because the customers have more than one problem, and the startup is solving a few of them well.

Stage 3: Becoming a platform by IPO (late stage / pre-IPO)

At the early IPO stage, the company is no longer building a platform, it has to already be one. The company is tackling a big category (think cloud, identity, network, endpoint, or SOC), and building multiple platforms for the same buyer. This is where platforms become “super platforms.” CrowdStrike is not just doing endpoint protection, it’s building a full threat detection and response ecosystem for the SOC.

Stage 4: The $100B+ mega platform (post-IPO / public scale)

At $100B+ market cap, a company is playing a different game, fighting for the opportunity to become a mega-platform. Here, it is expected to have multiple “big rocks” (core cybersecurity domains), each with its own product family, and to serve multiple buyer personas. The scope of the buyer expands, often going from the head of security to the CISO to the CIO. Palo Alto, for example, has something for everyone - teams in charge of SOC, cloud, network, application security, and more.

“Big rocks” in cyber

The areas we call “big rocks” of cybersecurity aren’t arbitrary. They reflect core, enduring categories of enterprise security that map closely to the Cyber Defense Matrix: users (identity), devices (endpoint), networks, cloud, application (appsec), and data. On top of that, there is the people, process, and technology that spans all of the asset types of the Cyber Defense Matrix, and that itself maps to security operations (detection and response across all areas). These are the gravitational centers of security spend, and every mega platform ends up owning more than one.

Early on, a company only needs to own one big rock: Okta had identity, CrowdStrike had endpoint, and Palo Alto and Zscaler had network. To become a mega platform, companies have to expand, and that’s exactly what we are seeing today:

Palo Alto isn’t just network anymore; they’ve pulled in cloud, data, and parts of SOC, to name some.

CrowdStrike is working hard to catch up, adding areas like cloud, identity, data, and more.

Zscaler just acquired Red Canary, signaling a strong desire to expand into security operations.

All these expansion attempts are deliberate, and the path companies take to get there matters a lot. Let us explain.

Imagine each big rock as a node in a three-dimensional space. Some are close to one another, but others are miles apart. Identity and data are close, as are cloud and network. Cloud and endpoint aren’t very close, but also not as far as, say, identity and application security. Companies looking to become mega-platforms by expanding into new areas can’t jump randomly - they need to expand to the nearest neighboring rock. Endpoint to operations makes sense, which is why CrowdStrike went from EDR to XDR to Falcon Complete. However, CrowdStrike didn’t end up going deep into the network, and that’s because of the proximity of the “big rocks”.

Zscaler, on the other hand, started with secure connectivity, and now they’re pushing toward SOC with the Red Canary acquisition. Whether they succeed depends on whether those rocks are truly close, or just look that way from a distance. So far, it doesn't look like Zscaler has been successful expanding from network into the cloud although to be fair, Cisco stumbled as well trying to make the same transition.

Palo Alto has aggressively executed on the proximity thesis. They turned the firewall into network security, then used that to expand into cloud and detection. Unlike Zscaler, they’ve been successful in getting into the cloud. Few people recognize that but it was Palo Alto who coined the term “platformization”, because it helps justify why a firewall company is suddenly doing CNAPP, SIEM, and even application security (think of Palo Alto acquisition of Bridgecrew).

Other expansions are different. Okta’s expansion into CIAM was ambitious and well-resourced. While the move made strategic sense from a portfolio perspective, it skipped over nearer adjacencies like IGA and PAM - large and relevant markets that aligned closely with Okta’s core. That sequencing created space for others like SailPoint and CyberArk to lead. CIAM remains a significant opportunity, but the move underscores how difficult non-linear expansion can be.

The “distance” between rocks isn't just about product, it’s a function of too many factors like talent, sales motion, architecture, and culture, which is why it’s so easy to make judgments in hindsight and so hard to make the right decisions when they matter.

Adjacency map: how cybersecurity domains connect

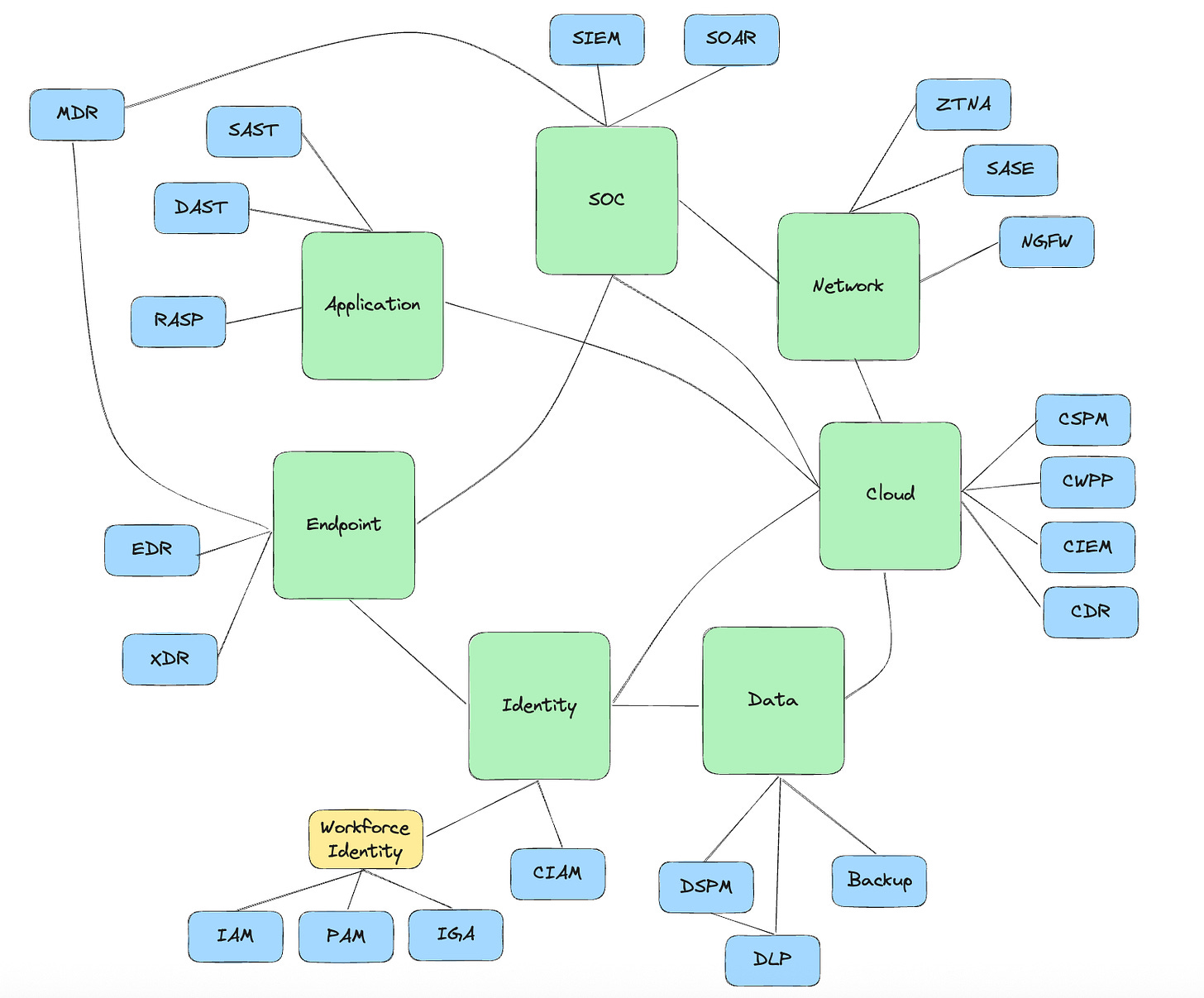

The visual below shows the major cybersecurity domains (“big rocks”) and their subdomains (e.g., PAM, SIEM, CSPM, etc.). In this representation:

Green boxes are big rocks like identity, network, endpoint, etc.

Blue nodes represent subdomains (e.g., SSO, SOAR, DSPM)

This map reflects how buyers think about cybersecurity domains, and how platform companies expand across them over time. The arrows between various nodes would show likely adjacency paths. A few points to note:

Closer rocks = easier expansion

Farther rocks = greater platform risk

Sequencing depends on buyer overlap, architecture, talent, and motion fit

This map is not meant to be exhaustive, and thanks to Gartner, we are sure we are missing numerous three-letter acronyms and categories! But the general idea stands - as companies grow, successful outcomes tend to be those that grow sequentially from one domain to adjacent domains.

Failure modes for different types of companies

One of the most critical questions to answer is what makes companies fail at different stages. Here’s our thinking about failure modes for different types of companies.

Most early-stage companies don’t fail because they picked the wrong rock, they fail because they couldn’t find a specific buyer with a need for their small single use case. Another critical aspect is figuring out where to focus and how to prioritize: although it is true that a startup must solve a specific use case, saying that it needs to be focused on that one single use case would be an oversimplification. Growth demands surface area, and eventually, they will need to do more than one thing. There’s never the “right time” to expand, so founders have to find a way to allocate 15-25% of time to building for expansion from day one.

When it comes to growth companies, their most common failure modes are not being able to earn the right to expand beyond the first use case, as well as trying to move too quickly without the trust of their core users. The latter is very important because too often growth-stage companies start churning out low-quality features in a chase of covering as many use cases as possible, but doing that tends to erode trust, not deepen it.

Mega platforms fail not because they can’t execute (they’ve proven they can), but because they reach too far, chasing rocks that are too distant. There aren’t many true mega platforms in cyber yet, so we don’t have a long history of mistakes, but the early signals are there.

Zscaler tried to get into cloud security and even made some acquisitions in that space, but the integrations never clicked. They’ve since quietly deprioritized those areas and are now refocusing new adjacencies like SOC. Cisco also tried to jump from networking into cloud by doing an acquisition, but ultimately it couldn’t become a big success there.

Palo Alto, for now, is the exception - not because all of their acquisitions ended up becoming big successes (many didn’t), but because they were able to execute them well, create the right incentives for the teams they brought in, and pulled off some real integration. Today, even they are at a point where every new move carries platform risk, so instead of going for some mega-mergers, they’ve been pretty smart about acquiring leaders in different segments when they are still early.

Closing thoughts

In all the discussions about building platforms, it’s too easy to lose sight of the core truths. One, that no company starts as a platform (regardless what founders put on their websites). The ability to expand is earned, one adjacency at a time. Second, that building a platform is a matter of sequential expansion and solid execution, not convincing Gartner to call you a platform. Don’t take us wrong - there are plenty of founders who understand all these things, and they will be the ones building the next generation of platform companies.