Why building security products is hard and why skilled security practitioners are the only way to achieve an advantage over the adversary

Looking at different types of attacks, why stacking tools on top of one another and using ChatGPT is not going to save us, and more

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Why technologies do not and cannot provide an advantage over the adversary

We have all recently been witnessing a lot of excitement in the cybersecurity space about the possibilities of AI, specifically - generative AI, large language models (LLM), and ChatGPT. Although only lazy people haven't written about how “AI is going to change cyber defense” (often - with the help of ChatGPT itself), the reality is a bit more complicated.

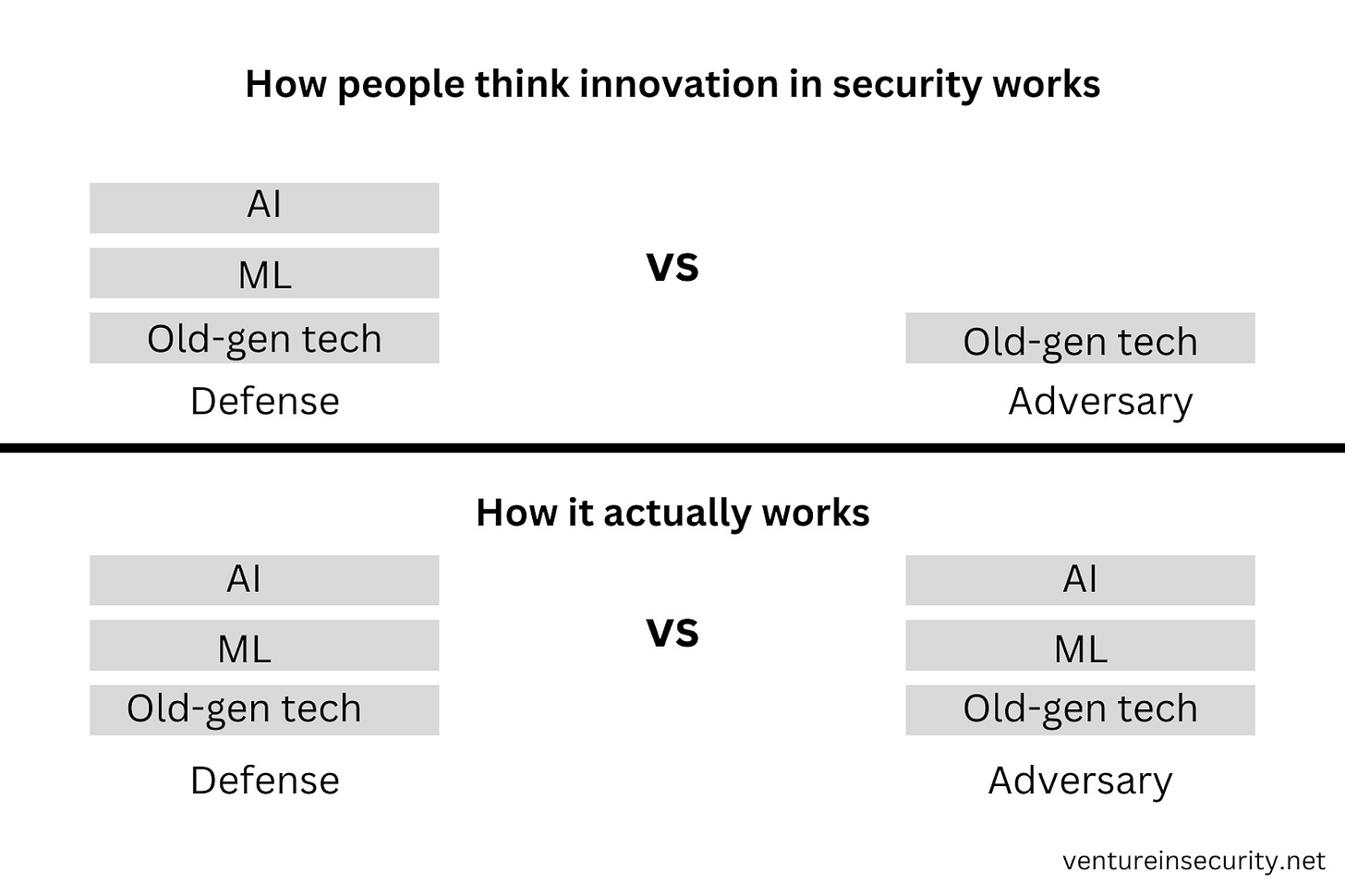

Any technological advancement - be it a cellular network, artificial intelligence, machine learning, cloud computing, 5G, or anything else - is an advancement achieved by collective intelligence. As such, it will always spread and gain adoption globally as soon as its existence becomes known. Technology is a form of knowledge, and it cannot be confined to the boundaries of countries, languages, or even patent protection. Any innovation keeps the playing field leveled as it is immediately available to good & bad actors.

Adversaries have access to the same tools as defense teams, be it AI, ML, cloud, or anything else. Not only that, but their access to data that can be fed into these tools is impressive as there is no privacy, GDPR, or any ethical considerations; anything will do.

The realities and natural shortcomings of security products

What it means to buy a “security product” and how it works

Fundamentally, when we say “a product X is securing my company”, what we mean is “another company, the technology it builds, and the people it employs are securing my company”. This explanation is better than simply saying “product”, but it still lacks deeper context. To illustrate how it actually works, let’s look at a specific example.

When a customer pays for an endpoint detection and response (EDR) tool, it typically expects the vendor to provide comprehensive security coverage. That coverage doesn’t come out of anywhere or is generated by AI alone. The EDR provider, to develop detection and response logic, hires large teams of security practitioners - threat intelligence professionals and researchers to stay on top of the new threats and prioritize what coverage the company should build, detection engineers who build and test individual rules and detection logic, and the like. This simple explanation should make it clear that security practitioners are at the core of how security is done even if they are shielded from direct contact with the customers behind the “product”.

Many factors distinguish one product vendor in the industry from another, but the quality of security talent the company can attract - vulnerability researchers & exploit developers, threat hunters, malware analysts, media exploitation analysts, OSINT investigators, detection engineers, architects, and others - is definitely one of the top five.

The business model of security product vendors

Knowing that paying for a security product is akin to hiring an outsourced security team is an oversimplification because there is another nuance worth explaining, and it has to do with the business model of security product companies. Let’s continue with our EDR example.

To successfully provide comprehensive security coverage, the EDR vendor needs to develop detection and response logic that both:

Catches all the bad stuff (does not generate false negatives)

Does not alert on the good stuff (does not generate false positives)

Since every customer’s environment is different, the EDR vendor is faced with an impossible task: developing detection and response logic that would apply to all of its customers, with no false positives and no false negatives.

Although meeting these criteria 100% is impossible, one could get pretty close by assigning a dedicated security professional (or better yet - a team of dedicated security professionals) to every customer. This would potentially enable the company to build generic logic in-house, and then fine-tune it to the needs of the individual companies they serve. This model isn’t possible as it would be prohibitively expensive for product companies to implement at scale and on a budget. There are other ways to achieve a similar outcome, but we will get to that later.

So, what do EDR providers do? Their goal is to create rules that apply to as many of their customers as possible without generating too many false positives. It’s a tough problem to solve as every rule that can be critical to 5% of the companies, can generate false positive alerts for the other 95% and vice versa. This is akin to sending all people in your company a t-shirt of medium size: for some, it will be too big, for others - too small, but statistically, it will fit and make the majority of the employees happy. Unlike in the t-shirt example, if a detection logic misses an adversary (as it often naturally will), the results can be catastrophic.

The business model of the security product vendors demands that they provide uniform, one size fits all coverage to all or most of their customers, leaving it to the customer to further customize the tool and make sure it reflects the organization’s reality. This is why relying on security tools alone is a bad idea, no matter what brand they were purchased from and what promises the vendor made.

Why assembling tools isn’t a solution

If each security product the company buys, be it endpoint detection and response (EDR), cloud security posture management (CSPM), network detection and response (NDR), data loss prevention (DLP), container security, or any other, isn’t tailored to its unique environment, then adding all of them together won’t lead to strong cyber defense. This should sound fairly obvious. There is, however, another reason why assembling tools isn’t a solution, and it has to do with the way technology works.

For security companies to develop solid in-house expertise, craft solid go-to-market strategy, and focus product development efforts on solving a specific problem, they have to pick an area to specialize in - think endpoint, cloud, data, code, and so on. Startups that have the ambition to cover a broad range of these segments at once and build a security platform, typically still need to start with one use case, and expand from there.

The problem is that, unlike security vendors, technology doesn’t neatly fit into segmented buckets. Everything is interconnected - the code, open source libraries, containers, cloud, identity, endpoints, and the like. While vendors have to define the boundaries of their coverage, sophisticated attackers targeting specific companies are looking for gaps all around, including on the edges of separate security areas.

Buying deeply specialized security tools and connecting them together resembles a tale about blind men and the elephant. The tale goes like this: “A group of blind people approach a strange animal, called an elephant. None of them are aware of its shape and form. So they decide to understand it by touch. The first person, whose hand touches the trunk, says “This creature is like a thick snake”. For the second person, whose hand finds an ear, it seems like a type of fan. The third person, whose hand is on a leg, says the elephant is a pillar like a tree trunk. The fourth blind man who places his hand on the side says, “an elephant is a wall”. The fifth, who feels its tail, describes it as a rope. The last touches its tusk, stating the elephant is something that is hard and smooth – like a spear.” - Source: an excerpt from the book, The Great Mental Models: General Thinking Concepts.

Image source: Farnam Street

Although identifying the shape of ears, legs, tusk, and tail is important, it is even more important to have the ability to piece all this together and figure out if what we are dealing with is an elephant, mammoth, or a cat carrying the walrus tusk.

Understanding the types of cyber attacks and how to defend against them

Battles of technology

There are many different types of cyber adversaries, different motivators that drive them, and different ways in which they accomplish their goals. However, if we were to simplify everything to the basics, I think that fundamentally, we are looking at two types of attacks:

Battles of technology (“spray and pray”)

Battles of people (targeted and hands-on)

Battles of technology are what I call mass attacks that typically use the “spray and pray” mentality. Adversaries know that many people and organizations lack the most basic security hygiene and defensive measures, and look for ways to exploit it at scale. The vast majority of the common attacks, including malware and ransomware, fall under this category. Adversaries do not know what are the exact companies that will become victims, but they know that a predictably large number will, so bad actors will get paid regardless.

With battles of technology, there are no people on the keyboard actively trying to break into the organization’s environment. Because of that, most of these types of attacks can be prevented with security toolings such as antivirus, endpoint detection and response (EDR), and others, especially if the tools are configured and fine-tuned to the organization’s needs. Furthermore, sound IT practices such as regularly executed and tested backups can bring the impact of these attacks to a minimum.

Battles of people

The second type of cyber attack - what I call “battles of people” - is targeted directly toward specific organizations.

When sophisticated attackers are actively working to find a way to break through the organization's defenses, technology alone is unlikely to stop them. Advanced threat actors have deep experience with the same security tools used by defense, and know how they work, where their gaps are, what can be exploited, and their take-out mechanisms. They attend defense conferences & spend time on forums where new ideas, tools, technologies, frameworks, maturity models, and the rest are discussed, so they know exactly what people on the defense are paying attention to, and what they ignore. They are talented, technologically fluent, and most importantly - highly motivated to achieve their goals.

The only way to win against the adversary is to have people - equally well-trained, talented, and motivated to stop the attack.

By adding security practitioners, either directly or via a technical security consultancy or a managed detection and response (MDR) provider, companies can solidify their security coverage:

Mature organizations cannot wait for detection to happen. They have to be proactive in monitoring new threats attackers, researchers, and red teamers expose, and checking if evidence of breach can be found in their organization's environment.

Mature organizations cannot hope that their vendor has them covered. They have to continuously assess what types of attackers constitute a threat to their type of business, what their methods are, and how they can be detected. They have to take into account the organization's unique environment and build logic to detect and respond to threats that are unlikely to be covered by a generic vendor solution.

People are not a replacement for technology, but a layer on top of it. For example, most mature organizations have an antivirus (AV) to cover their basic needs, and an EDR or XDR (extended detection and response) on top of it to alert on what is outside of the AV’s realm. They do, however, also recognize that an XDR is not a magic solution - it is a generic tool that is not specifically tailored to their unique environment and needs. In the past few years, we have learned to think of antivirus as a basic solution, and started seeing XDR as an advanced option. Now, it’s time to recognize that they are both foundational layers of security, but without security expertise on top of tools, no organization can hope to future-proof its security posture.

Importance of moving from promise-based to evidence-based security

Mature organizations have to take control of their security posture. Threat hunting is one way to do it; building custom detection logic to cover the gaps vendors could not foresee is another. To get to that level, security teams need full control over their security infrastructure that enables them to access all of their telemetry, build high-fidelity detection logic, send their data to any external destination, and so on. Security vendors have to recognize that they cannot lock their customers into their own ecosystem - not only is vendor lock-in a bad practice, but it also prevents companies from being able to improve their security.

I often talk about the move from promise-based to evidence-based security. It is where I am convinced the industry is moving.

“Mature security professionals know that security is a process, not a feature. The best way to build a security posture is to build it on top of controls and infrastructure that can be observed, tested, and enhanced. It is not built on promises from vendors that must be taken at face value. This means that the exact set of malicious activity and behavior you’re protected from should be known and you should be able to test and prove this. It also means that if you can describe something you want to detect and prevent, you should be able to apply it unilaterally without vendor intervention. For example, if a security engineer has read about WannaCry, they should have the ability to create their own detection logic without waiting a day or two until their vendor does a new release. - Source: Venture in Security

For those curious about the shift from promise-based to evidence-based security, I’d recommend the following articles:

Future of cyber defense and move from promise-based to evidence-based security

The rise of security engineering and how it is changing the cybersecurity of tomorrow

Managed security service providers: present state, trends, and future outlook of the space

We cannot continue to build security based on marketing promises and assurances from vendors that they will “keep us safe”, because we know that it is not how it works. We know that when a security provider claims “100% MITRE ATT&CK coverage”, it means nothing: there are tens of different ways to detect any specific behavior, and many are highly dependent on the customer environment. This is akin to saying that “our pills cure 100% of all cancer cases” while ignoring the fact that not only we aren’t currently able to do that, and that the causes, context, and pre-existing conditions for each case are different, necessitating a different treatment.

For us to move from promise-based to evidence-based security, we need to stop relying on vendors to identify the bad stuff. Whatever detections and alerts are provided by security companies are simply a foundational layer devoid of the organizational context. To move above this basic layer, companies need to hire and develop security talent - threat hunters, detection engineers, researchers, intel practitioners, and the like. Triaging and investigating alerts triggered by vendors is not even remotely enough to protect the organization.

Achieving the advantage against the adversary

Building security products is hard. Vendors are faced with a challenging and I dare to say fundamentally unsolvable problem: how to build a generic tool that can apply to anyone on the market even though each customer is different. I am not suggesting that security vendors are doing a bad job, but trying to make it clear that relying on products alone to achieve security is not the right way to do it.

We have to push vendors to do better when it comes to their capabilities, the way they market their products, and the way people can access them. However, it is critical to recognize that no tool, however powerful, transparent, vendor-agnostic, and AI-enabled it may be, cannot help companies achieve an advantage against sophisticated adversaries. The only way to do it is to rely on people - security practitioners that are talented, highly proficient in understanding different layers of technology, and as motivated to achieve their goal as the attackers.

Companies hoping to outsmart and outpersist attackers have to invest in people over tools. This means:

Hiring for practical skills and abilities

Recognizing talent and looking beyond work experience and credentials

Being willing to give a chance to hungry yet junior security enthusiasts

Investing in developing people and helping them grow to realize their true potential

Unfortunately, it does appear that hiring practices haven’t been keeping up with real-world threats, and there is still a lot of bureaucracy and gatekeeping. Adversaries, on the other hand, do not require a decade of experience, and an alphabet soup of certifications. They are evaluating the drive, technical proficiency, and ability to achieve real goals. It is this simple fact that can enable them to stay ahead of the defense unless we change how we identify, recruit, compensate, build, and treat security talent.

Tools are just that - tools; while ChatGPT can be used to enable bad actors to craft phishing emails, it can also help defenders like the GPT-4 Assisted Detection Engineering article by Brendan Chamberlain shows. Security vendors themselves know that by investing in their marketing and positioning the company as the #1 place for top talent, and by building solid products, they can attract the best security practitioners. That, in turn, makes their products even better, further supercharging this talent flywheel, attracting top security talent from the frontlines, and so on. No matter what corner of the industry we look at, it is apparent that people, not tools, technologies, approaches, or matrices, are the key ingredients needed for the defense to win.

This is a great article, Ross, and it's aging like good wine.

Ross, Spot on! Unfortunately, the people challenge is not going to get solved soon, due to the sheer size of the skill gap today. In my view, one potential path forward is to have AI tools that can work across vendor products and assist the security teams to focus on right priorities.