Using behavioral science to build stronger defenses

Discussing behavioral psychology and its role in cybersecurity

Cybersecurity is usually seen as a technical problem. There are security controls, detection logic, encryption, and other pretty technical concepts. However, at the core, it remains a human issue: users making quick decisions under pressure, analysts triaging endless alerts, and executives deciding on trade-offs. Most of the time when I hear security people discuss human behavior, the conversation is centered around how we need to train, educate, and test people, or even more fun, turn them into “human firewalls”. What gets lost is that the human mind is not purely rational, and a lot of how we see the world and how we behave is shaped by the patterns that psychology calls cognitive biases.

I have long been fascinated by how biases impact our decision-making. Many years ago, I went super deep into reading Daniel Kahneman, Dan Ariely, and Richard H. Thaler, among others. As a product leader whose job has been to work with different stakeholders and to build products people love, I found behavioral economics and decision science incredibly useful. Years later, when I moved into cybersecurity, I was (and still am) surprised by how little discussion there is about behavioral science and its role in cyber. This is going to be the focus of this week’s article. This piece is going to be different because it’ll refer to a lot of other sources (I am not a psychologist, only an enthusiast and someone passionate about this topic).

This issue is brought to you by… Permiso.

Permiso’s new ITDR playbook: turn identity blind spots into detection wins.

We’ve broken down the 5 categories of authentication anomalies that catch the vast majority of identity attacks and paired them with ready-to-use detection rules and thresholds. No guesswork, just practical implementation guidance.

Why it matters:

Detection rates for compromised identities have dropped from 90% to 60% in the past year.

Attackers don’t need to break in: 90% of successful breaches start with logging in.

Once inside, they can begin lateral movement in as little as 30 minutes.

This playbook shows how to close that gap with risk-based response procedures and investigation workflows that actually work in practice.

Start detecting what others miss, and grab your copy today.

Cognitive biases 101

Here’s how Wikipedia defines cognitive biases: “A cognitive bias is a systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment. Individuals create their own 'subjective reality' from their perception of the input. An individual's construction of reality, not the objective input, may dictate their behavior in the world. Thus, cognitive biases may sometimes lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, illogical interpretation, and irrationality.”

The main idea here is really simple. The human brain relies on shortcuts (often called heuristics) to quickly make sense of complex information. These shortcuts allow us to navigate the uncertainty and complexity of our surroundings without having to think hard about every single action we take. For example, when crossing the street, we don’t calculate the exact speed of the moving vehicles; instead, we look around, make a quick decision, and start crossing if it “feels” safe. When we go shopping, we usually think that the item that is more expensive is of higher quality. When someone repeats the idea we’ve already heard before, we are more likely to assume that it’s true compared to something we heard for the first time (even though we didn’t verify either of them). All these are biases and mental shortcuts.

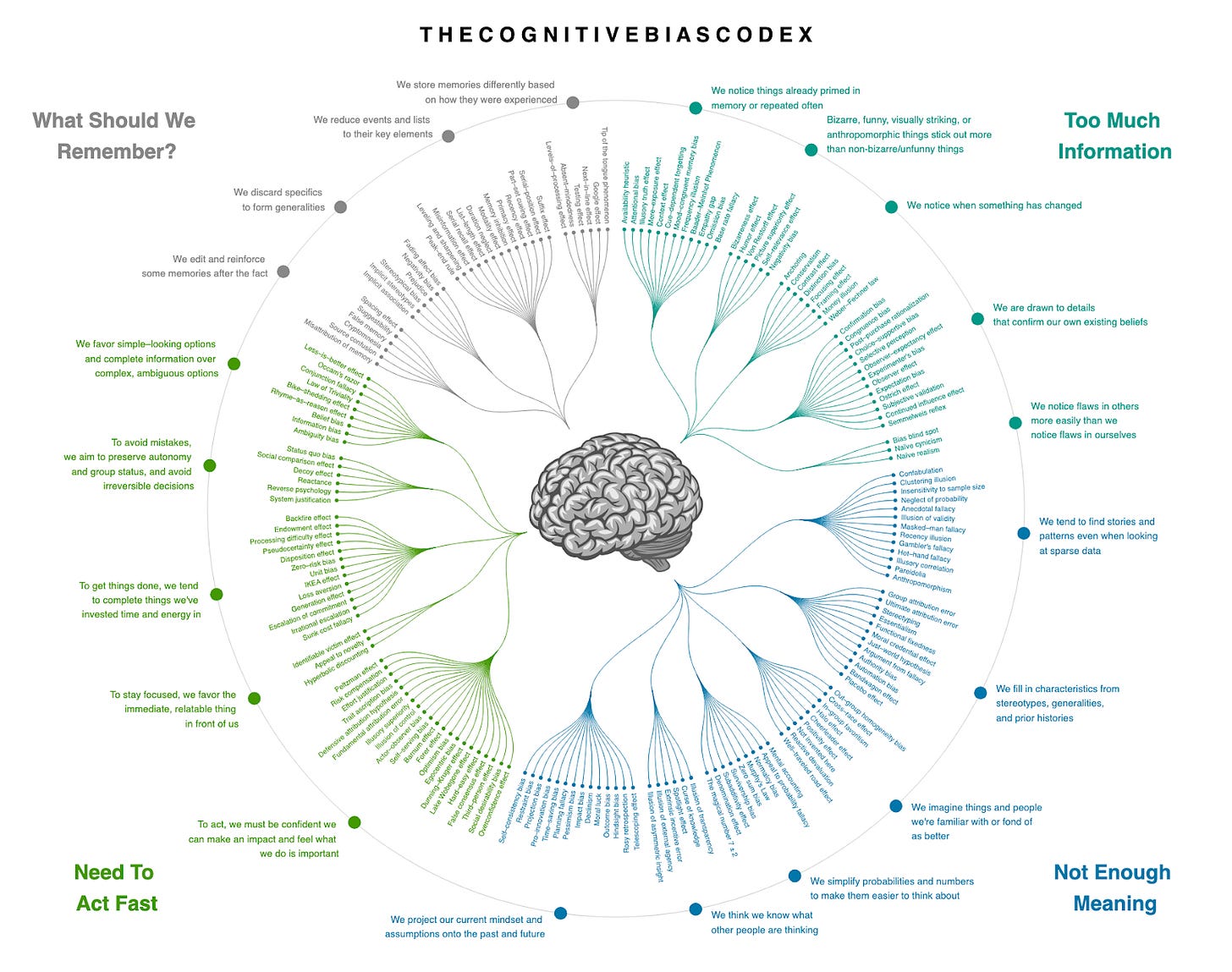

Image source: Wikipedia

These biases impact how we see the world, form opinions, make decisions, and remember past events. In everyday life, they explain why we are willing to pay more for things that look exclusive, or why two people will often remember the same event differently. In cybersecurity, these biases are critical because they get exploited by attackers, impact how cyber defense teams do their jobs, and can be used to make people behave more securely.

How attackers exploit human biases

In a way, social engineering is a form of applied psychology: the success of the attackers depends on their ability to exploit predictable deviations in human judgment. Let’s briefly touch on some of the most common biases attackers exploit and what security teams can do to protect people.

Authority and halo bias

Authority bias is our natural tendency to trust and comply with instructions from people with authority. A good example is the fact that we use people’s uniforms as a shortcut to legitimacy. Think of police attire, military dress, or even a doctor's white coat: wearing a white doctor’s coat increases people’s perceived authority, even if what they are saying is completely bogus. The halo effect is when a single positive characteristic of a person, like professionalism or the ability to speak convincingly, makes people assume that they can be trusted in other areas. We see this very often in our day-to-day lives: people assume that a successful tech executive will be good at politics, that a famous TV star should be good at running businesses, and so on.

Attackers know this is how our minds work, and they have learned how to take advantage of it. Emails “from the CEO” or “from the CFO”, fake IT helpdesk calls, or well-designed login pages rely on these instincts to put us at ease. It’s ineffective to assume that we can simply train people to be vigilant. The most effective way to design around these biases is to disrupt the default flow. One example would be to build flows that require out-of-band verification for sensitive actions, which would break the default behavioral pattern of simply doing what a person with authority says.

Present bias and urgency

Another interesting heuristic is what’s called present bias: when making decisions, people tend to focus more on the present situation instead of the future consequences of their actions. This is why 60% or more talk submissions for every CFP are sent hours before the deadline, why people procrastinate, and so on. Attackers know that this is how our minds work, but to make it even more likely that we will fall into their traps, they combine presence bias with another strong factor, urgency. When we see signals that something is urgent, we feel forced to act fast, thinking that there’s no time to think. Phishing emails with countdown timers, ransomware demands victims have to pay “within 24 hours,” and “approve this request now” calls to action are all examples of these biases in action.

The same methods that work for dealing with authority and halo biases are useful here: introducing deliberate, useful friction on high-risk actions. This may be a 60-second hold-to-confirm prompt, or a short verification delay, anything that buys a person time for reflection and breaks the illusion of urgency. Adding steps that involve out-of-band confirmation or involving other people are even stronger, because when more people are involved in some process, the chances that at least one of them will realize something is off increase.

Framing, fluency, and illusory truth

Humans don’t just respond to facts, we respond to how they’re presented. This is known as the framing effect: the same information can feel different depending on wording or context. Fluency is another shortcut - when something is easy to read or process, we instinctively trust it more. With illusory truth, the more something is repeated, the more familiar it feels and therefore the more trustworthy we think it is. This is exactly why we believe misinformation more easily when it’s repeated many times, by the way.

These biases, especially when combined, directly impact how we process information. Attackers know this, so they design their messages to be smooth, simple, and repetitive. This has been a problem before, but now with AI, it’s getting even worse because language is no longer a barrier, and attackers can use LLMs to tailor messages to individuals more accurately than ever before. We see this urgency at play in most social engineering attacks: “Your account is at risk” (usual phishing pattern) is a much scarier and more urgent framing than “We noticed unusual login activity”. Attackers use familiar patterns, such as suspicious activity emails, and essentially weaponize them against us.

The best way to reduce the chances that attackers will be successful when taking advantage of framing, fluency, and illusory truth biases is consistency. The problem is that most tech companies are very inconsistent with their messages, and many send emails that look like phishing attempts even though they aren’t. This lack of consistency is an issue. Security warnings should be written in plain language, and alerts like account notifications should frame issues around facts people can verify, not emotional hooks that drive urgency.

Loss aversion and scarcity

People feel the pain of losing something much more strongly than the pleasure of gaining something of the same value. This is called loss aversion. If we lose, say, $100, we will be much sadder than we would be happy if we found $100. Scarcity works in a similar way: when something looks rare or more exclusive, like memberships in executive clubs or “limited edition” products, we immediately treat it as more valuable. These are natural instincts, and they get triggered very easily. Attackers are really good at creating fear of loss or urgency around scarcity. This is why they send messages like “Your account will be suspended unless you act now” (loss aversion) and “Only the first 100 people can claim this reward” (scarcity) to create pressure so that people don’t stop to think.

Tech products should be designed around people’s biases. There is no reason why we can’t warn people that something is suspicious and that they should be extra careful by simply understanding the tone of the message. We should get better at recognizing intent and warning users when it looks like someone is trying to take advantage of these tactics. At the same time, security teams should still prioritize building guardrails to protect people against themselves, so even if someone feels the pressure, the system would prevent them from doing something bad without proper checks.

Default effect

There are many more biases than we can cover in a single article, but one that I do want to briefly touch on is the default effect. When faced with a choice, people tend to accept default, pre-selected options. This is why the most popular coffee size is medium, and also why the vast majority of people always end up with the default health insurance plan. Default options are the safest and the simplest to accept. It is this same bias (and not that people don’t care about security) that makes people stick with weak default passwords or not opt into stronger authentication. The best way to deal with this bias is to ship secure defaults and remove weak options entirely. This may mean disabling the SMS MFA, but it can also mean limiting the ways in which people can make changes to the cloud, and so on.

Biases that impact security teams

While security teams like to preach security awareness as the best solution to all the problems, they themselves are not immune to the same psychological shortcuts that attackers exploit in people they are hired to protect. Here are just a few of the psychological biases that impact the quality of work of security teams.

Detection and triage

Some of the most common pitfalls in detection work are availability and recency biases. When analysts and detection engineers prioritize what to focus on, they will first pay attention to the threats they’ve read about in the news or on social media. This leads to skewed prioritization, where threats of the day that happen to make headlines get more attention than the issues that are much more likely to get the company breached. The solution here would be prioritization and discipline around focusing on what’s important over what’s in the news.

Another recurring challenge is confirmation bias. Once an analyst develops an initial hypothesis (say, “this is an insider threat”), the natural instinct is to look for evidence that proves this hypothesis and ignore anything that disproves it. This tunnel vision can lead to chasing the wrong problem for far too long. It’s very easy to suggest that people should be open-minded, but the reality is that we’re all susceptible to the impact of these biases, so it’s easier said than done.

Security analysts have to deal with the never-ending stream of alerts, each of which can be a sign of a compromise. It’s very easy to get impacted by what’s known as attentional bias, when a single alert or anomaly consumes all the attention, and other important things get ignored. While the very nature of the security work makes attentional bias a feature, not a bug, it’s important to intentionally plan small pauses that create breathing room and widen the lens when people are deep into their work.

I think that some of the most dangerous biases are those that make security people overconfident, or even make them develop an exaggerated sense of their own ability to protect their companies from being breached. The three phenomena worth calling out are the overconfidence effect, illusion of validity, and Dunning-Kruger effect. Each of these is slightly different (Wikipedia does a great job of explaining them, so I am not going to do that), but all three lead to the same result: making people overestimate their skills and abilities and become overconfident in their beliefs. Some fall into this trap when they see data that fits neatly into a coherent story, and others simply don’t know enough to see their own limitations. In theory, there should be ways to deal with these, like assigning likelihood to different judgments, etc. However, as the saying goes, in theory, there is no difference between theory and practice, but in practice, there is. In practice, the best we can do is to maintain awareness that we are all subject to biases that can distort our view of the world and impact our decisions.

More biases impact our ability to detect and triage issues than what we can cover here, but the one that I simply have to include is automation bias. Humans tend to assume that machines are correct and trust the output even if it’s questionable. AI and the rise of AI agents take this problem to an entirely new level since companies are agentifying more and more workflows, and with that, we are seeing more and more automated reasoning. Security teams should demand transparency from their vendors and make sure that machine recommendations always include an accompanying explanation that can be verified.

Risk assessment

If you think security teams are able to rationally analyze their risks, think twice. Humans are always impacted by different biases, and it’s well-known that we are pretty bad at making sense of risk. Let’s briefly talk about some of these biases and ways in which they impact risk assessment.

Base-rate fallacy is what happens when high-profile threats like APTs and zero-days get all the attention, while more common causes of breaches, such as misconfigurations or weak credentials, get ignored. Proportionality bias, according to Wikipedia, is “the tendency to assume that big events have big causes”. We see this all the time in cyber: when a big breach happens, there is often an assumption that the reason must have been very sophisticated, even though in practice, many catastrophic incidents come from the simplest of errors, like an unpatched system or a default password.

Discussions about risk are clouded by normalcy bias and optimism bias. Normalcy bias leads people to underestimate the possibility of disasters such as ransomware attacks simply because they have not yet happened. Optimism bias convinces companies that they are less likely to be hit than others. Together, these biases lead to under-investment in security and under-preparation for rare but really devastating events. These two biases are the exact reason why people believe that they are “too small to be attacked” or that “they don’t need cyber insurance because nothing bad is going to happen”. The only way to get around these biases is to force people to experience the unthinkable events through tools like simulations and tabletop exercises that get them to imagine that bad things have already happened, and think about what they’d be doing to deal with the consequences.

Hindsight and outcome bias distort how organizations, as well as an industry, learn from incidents. Once a breach happens, it is tempting to see it as obvious in retrospect. Decisions that seemed reasonable at the time are judged negatively because the outcome was negative. In security, these two biases are largely responsible for what I can only describe as victim shaming. After a big incident happens, you’ll see all sorts of cyber influencers taking to social media to say how it was “obvious” that not fixing some vulnerability or not having some latest tool or whatever will eventually backfire. In practice, we all know that most companies are a mess, most CISOs are trying their best, and that in security, it is often helpful to separate the process from the outcome. Oftentimes, when we look back, it becomes clear that most of the decisions that led to breaches were actually good decisions, given the context and the information available when they were made. For anyone who is interested in learning more about these specific biases and the concept of resulting, I’d highly recommend “Thinking in Bets”.

Security management

When I say that all humans are affected by psychological biases, I don’t just mean employees who “don’t follow what they learn were told at the awareness training”, security analysts who give in to biases when trying to detect and respond to threats, or different stakeholders outside of security who cannot imagine that their company can get breached. CISOs and security executives are very much under the influence of the same biases.

One bias that is known to quietly drain resources is sunk cost, or escalation of commitment. Once time and money have been invested in a tool or project, it becomes psychologically difficult to abandon it, even when it is clear that it is failing. Oftentimes, security teams keep pushing because “we’ve already spent too much to stop now”, and execs feel like they cannot abandon the project without damaging their reputation. This is why companies tend to keep going forward with initiatives that are not going anywhere, and why they stick with poor security tooling even after there are already better alternatives. This is also why big platform vendors like to give away their products for free just to get companies to deploy them: once a company implements a proxy or an enterprise browser, status quo bias and sunk cost bias will make executives keep them even if there are better alternatives (“we’ve already implemented it, so why would we change if it’s working”).

Technology choices are also defined by the law of the instrument: when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Security teams and security leaders alike tend to stick to tools they know, even if those tools aren’t the best fit for the problem. This leads to over-reliance on familiar technologies and under-exploration of better alternatives. This is exactly why a CISO who is an ex-GRC leader will often over-optimize for compliance, a CISO who is an ex-security engineer will often over-invest in building tools in-house, a CISO who is an ex-law enforcement will prioritize insider threat, a CISO who was a head of IAM will often over-invest in identity at the expense of other areas, and so on. This can get pretty fun to watch because oftentimes, you can guess who the CISO was in their past life by asking about their priorities for the team. To be clear: there’s absolutely nothing wrong with doing what works, or sticking with what the person knows based on their experience, as long as that’s not done to the detriment of equally important areas, but that may not get as much attention simply because the security leader isn’t as well-versed there.

Lastly, organizational decision-making in security and beyond is heavily influenced by groupthink and shared information bias. Teams naturally gravitate toward consensus and spend too much time discussing information everyone already knows, while spending less time on information that only some people know. This creates blind spots in the very areas that need to be discussed more often. To prevent this from happening, it’s helpful to have a person in the room whose role is to argue against consensus and collect pre-read inputs individually so that unique information gets surfaced before group discussion dilutes it.

Using biases to ethically promote secure behavior

While it is true that human biases play a very important role in cybersecurity, I am not suggesting that they always work against us. Security professionals can lean into biases intentionally and use them to make secure behavior easier, more natural, and more likely to stick. The same mental shortcuts that attackers manipulate to get people to do something they shouldn’t be doing can be turned into design tools for defenders.

Take the default effect and status quo bias. People tend to stick with what’s given to them, leave things as they are, and resist unnecessary change. Instead of treating that as a bug, security teams can lean into it by shipping secure defaults. If some security feature is enabled out of the box, most people will simply accept it instead of going through the trouble of figuring out where and how to bypass it. The trick is that it has to be simple, and it cannot introduce a lot of friction (people will do anything to get rid of friction). Combine that with a mere exposure effect, which makes people prefer what feels familiar and easy to process, and it becomes clear that security should also look and feel consistent. It’s easier for people to get used to some security controls if they are consistent, if they come with the same UI, icons, and language.

The framing effect offers another opportunity. People interpret the same facts differently depending on how they are presented. If SSO were described as “an extra step,” it would feel like friction, but because it’s sold as “fewer logins after setup,” it feels like a convenience. Patching can be sold not just as “better security” but also as “faster performance” or “improved stability.” Framing the benefit in terms of what people care about day to day makes adoption more likely. Take Chainguard, for example - they frame their product as a way for developers to not have to deal with security requests, which works better than if they were to try and convince developers to care about security (we’ve seen how that works with shift left).

Even the effort justification effect, sometimes called the IKEA effect, can be used positively. When people put effort into something, they value it more (I previously explained how this exact bias makes some product categories in security very successful). Security teams can get buy-in by involving engineers in co-creating guardrails or policies. When people feel like they were a part of creating some process, they will be much more bought-in, and they won’t feel like security pushed something onto them. That sense of ownership makes it easier to get people on board to follow the new process (after all, they helped to create it).

Finally, memory biases like the salience bias and peak-end rule remind us that people are pretty bad at accurately remembering the whole experience; instead, they remember what stands out and how it ends. Security teams can design flows and ask their vendors to build products in ways that make risky actions visually distinct. At the same time, security tasks and interactions with security teams should end on a positive note. If the last touchpoint is positive, the overall memory of the task will be too, increasing the chance people will do it willingly again. And, if the highlights of interactions with security teams are positive, people may actually start coming to them with questions and treating security more as advisors vs. a policing function.

Closing thoughts

This article ended up being very different from my usual articles, and for a good reason. There are well over 180 cognitive biases that impact the way we see the world, think, and do things. These biases are a huge part of how we all act, and not quirks that we can just train away by getting people to complete mandatory training. I have always been a huge fan of psychology, but I still learned a lot while working on this article.

I think behavioral psychology and decision science should be mandatory for anyone getting into security. As of right now, CISSP and other respected programs and degrees do a great job teaching security practitioners and leaders about technology, but I think it’s fair to say that they do a pretty bad job helping security practitioners understand how humans operate and how their brains are wired. The good news is that over the past several years, I’ve been seeing a growing recognition of the importance of soft skills and communication in cyber. The bad news is that I am still not seeing much emphasis on human psychology.

I strongly believe that security of the future will be much less about technical controls (although technology will only continue to be more and more complicated), and much more about behavioral design and embedding behavioral engineering into technology. The path forward simply cannot be endless awareness training. We need bias-aware design: defaults that are secure, processes that account for biases and how humans actually operate, and systems that guide people toward the right choice even under pressure. We won’t get much by expecting that we can turn people into robots trained to recognize signs of badness; instead, we need to work with what we’ve got, and adapt security tooling to people, not people to security tooling.

Lastly, if you are interested in learning more about behavioral economics, decision science, and how human brains operate, I suggest checking out these few books to start:

Really enjoyed this read

Could not agree more that behavioural science is not being thought about enough in general in the world of cyber security. But companies like Redflags (previously ThinkCyber) have been talking about this since 2017!!!

Even a basic understanding of learning science and behavioural theory will tell you that annual ELearning and phishing sims are NOT the right solutions to this problem. And have no measurable long term impact.

Taking the understanding of bias further, all decisions take place in context. So that is where we have to help people. Delivering interventions in real time, shaping choice architecture and measurably impacting behaviours.

We are seeing change. Forward thinking organisations get this and are seeing incredible measurable reductions in behavioural risk.