To solve security problems, you don’t have to build a security company

Security as a byproduct often leads to more lasting security impact than security as the product.

I have been thinking about this idea for a while, but only recently reached the point where I can clearly visualize how it actually works, so here it goes. If you were to ask security founders what they think are the best ways to make companies more secure, they would probably tell you different ideas about getting CISOs to buy new security tools. That’s not wrong per se - CISOs control security budgets, set strategy, and are responsible for the organization’s security posture. This thinking, however, is very limited for a simple reason: some of the biggest improvements in security have come from products that were never sold as “security” at all.

In this issue, I discuss the concepts of security as the product vs. security as a byproduct, and what they mean for founders.

This issue is brought to you by… Maze.

AI Agents That Triage Vulnerabilities for You

Vulnerability management is broken -bloated backlogs, endless false positives, and constant pressure. Maze changes that. Our AI agents autonomously triage and resolve cloud CVE findings, cutting out the noise so your team focuses on what truly matters.

Think of it as having expert security engineers on demand: contextual, precise, and always on. Faster fixes, fewer escalations, and finally, a backlog you can get ahead of.

Security as the product vs. security as a byproduct

There are two fundamental ways to deliver security: security as the product and security as the byproduct. When security is the product, security is the core thing the company sells. All the companies we know as security vendors fall under this category, from endpoint detection and response, cloud prevention, to vulnerability scanners and firewalls. Each of these products is marketed and sold more or less the same way: “Hey CISO, if you don’t buy what we are selling, you’ll get breached and/or fail a compliance audit”.

Security as a byproduct, on the other hand, means the customer buys your product for a different primary reason, be it productivity, user experience, cost savings, speed, etc., and security is simply a side effect of using it. The buyer probably doesn’t even think of the product as a “security tool,” but the security benefit is real, measurable, and in some cases far greater than what a traditional security product could deliver. In fact, some of the biggest security improvements came from companies that don’t even market themselves as security players.

Five case studies of security as a byproduct

Security as a byproduct of a simpler experience (Chromebooks)

Chromebooks are a great example of security being a side effect of simplifying the user experience. The core pitch of Chromebooks was never “buy this because it’s resistant to ransomware”, it was “buy this cheap, easy, low-maintenance laptop that has everything you need and that you can access with your Gmail account”. By stripping away local storage, restricting software installation, and isolating everything in the browser, Google removed a huge attack surface area that kills traditional PCs. With Chromebooks, malware protection isn’t the product, it is the inevitable outcome of the design.

Of course, there are plenty of challenges around user experience with Chromebooks, and most businesspeople need laptops that can natively support all the bells and whistles of the Microsoft Office stack. And yet, aside from implementing MFA, getting people to use Chromebooks is probably the single most impactful change companies can make that would lead to better security.

Security as a byproduct of a better communication channel (Slack)

There are many great email security vendors working hard to protect how companies communicate, such as Sublime, Material, Abnormal, and even some stealth teams. While their work is undoubtedly important, I would argue that Slack has done more to stop phishing than all the dedicated email security vendors combined. They did it not by building a more sophisticated AI to filter out bad emails, but by getting rid of internal email as a primary communication channel altogether. By doing that, they significantly reduced the biggest attack surface for phishing.

Nobody needed a security awareness training session to understand why Slack was better than Outlook. People wanted faster, searchable conversations, fewer reply-all chains, and real-time collaboration. The security benefit was invisible but powerful: fewer malicious links are reaching employees, fewer spoofed messages are getting through spam filters, and most sensitive internal discussions have moved away from the heavily targeted system. Sure, security practitioners can argue that Slack itself isn’t bulletproof, but I think that argument here is irrelevant because of how little of a problem Slack security is compared to email security.

Security as a byproduct of sales enablement (Vanta, Drata, Secureframe, Scrut, etc.)

We can have all kinds of debates and say that “compliance is not the same as security” or that “companies should focus on real security and that will make them compliant by default”, but the reality of life is that it is not how things are. Security is most definitely not on the list of the top 20 concerns of any early-stage startup; their number one concern is getting customers, so anything that helps startups close more deals will get their attention. This is where compliance comes in: startups want to sell to enterprises, and those enterprises require SOC 2, ISO 27001, or similar certifications.

Companies like Vanta, Drata, Secureframe, Scrut, and others are essentially providing startups with sales enablement tools in the form of compliance (“get SOC2 so that you can start selling to large companies”). The side effect is that, in meeting the requirements, startups also implement real security controls like access reviews, encryption, and monitoring, that they would probably never have prioritized otherwise. Compliance isn’t a perfect proxy for security, but without the sales incentive, many companies wouldn’t even do the bare minimum. SOC2, on the other hand, often drives above-minimum controls and an improvement to security posture.

Security as a byproduct of easier access (Okta)

Although Okta is now definitely in the “security company” category, its origin was all about convenience, not cyber. The early pitch was simple: one login for everything, a single password to remember, and no need to deal with dozens of credentials. This was about productivity and reducing helpdesk tickets for password resets, not about “identity security” in a traditional sense.

However, the architecture that enabled this convenience (centralized authentication, single sign-on, and granular access control) also eliminated many of the security weaknesses in traditional credential sprawl. It meant fewer reused passwords, faster deprovisioning when employees left, and easier enforcement of multi-factor authentication. Users and IT teams adopted Okta to make life easier, but in doing so, they really raised the organization’s security without ever thinking of it as a “security project.” Today, Okta is as much a security company as, say, CrowdStrike.

Security as a byproduct of productivity (Chainguard)

Another example of a productivity improvement company that helps achieve security outcomes is Chainguard. CISOs have all the reasons to love products like Chainguard, but it is not in a traditional sense a “security tool”. Chainguard doesn’t go directly after the problem of security teams needing secure container images. Instead, it solves the problems of developers who are forced to waste time patching and maintaining container images. Chainguard’s pitch to developers is not “Be more secure”, it is “Your security team keeps asking you to patch containers. Imagine never having to deal with that again.” By offering continuously updated, verified container images, they remove a repetitive chore and restore trust in the build pipeline. Security here isn’t the top-line feature; it’s the natural outcome of solving a workflow problem that engineers actually want fixed.

To solve security problems, you don’t have to build a security company

The main point of talking through these examples is that people in security need a mental shift. Most founders assume that if they want to solve a security problem, they need to build a security product, market it to CISOs, and go after the security budget. In reality, if the goal is to achieve a security outcome, this can very well be the hardest, slowest, and least successful route. The alternative is to embed security into a product that already has demand for other reasons, where adoption is driven by clear, non-security value. In many cases, the approach of treating security as a byproduct, not as a product, delivers faster adoption, broader reach, and ultimately, a bigger impact on real-world security outcomes than any standalone tool could achieve. Think about it:

Chromebooks did more to reduce the risk of ransomware than most EDRs. People adopt Chromebooks because they are cheap and easy to set up and get better security “for free”.

Slack did more to reduce phishing than most email security tools. Companies adopt Slack because it offers a much better collaboration experience than email and get security “for free”.

Vanta did more to improve the security posture of tech startups than most consultancies. Startups would get Vanta so that they can start selling to enterprises and get security as a byproduct of that, “for free”.

Okta did more to improve identity security than many dedicated security vendors. IT teams would get Okta to make it easy to provision access and get security “for free”.

Chainguard did more to improve the state of container images than any vendor that does vulnerability scanning and generates tickets that need to be fixed. Developers buy Chainguard so that they don’t have to deal with security requests to constantly patch container images and get security “for free”.

Needless to say, this list of examples is not exhaustive, and all of them illustrate the same point: that to achieve a security outcome, founders don’t necessarily have to build a security company.

Applying this mindset towards solving emerging problems

The idea that security outcomes can be achieved by companies that aren’t specifically targeting CISOs can also be successfully applied to forward-looking, emerging problems. Let’s take a brief look at two areas that are becoming more and more relevant with AI, secure code and security for hiring.

There is a lot of discussion about the fact that AI-generated code is not inherently secure. When I think about this problem, I wonder what the solution is going to look like. One way to solve this is to do what was done before: build a “next-gen” code-scanning tool and sell it to security teams. Another way to do it is for developer platforms to embed AI-assisted vulnerability detection directly into the coding process. This way, developers would adopt it for productivity, and security would come along “for free”.

The same can be said about another huge issue, namely, the rise of deepfakes and the breakdown of online trust. One of the most urgent manifestations is the problem of hiring North Korean developers. There are plenty of great deep dives about what’s happening, so I will spare you from re-explaining the basics. The question is, what can be done about it? Here, I think, we also have two paths. One is to build a security solution that would ingest signals from different systems and attempt to detect deepfakes. This LinkedIn discussion gives a pretty good idea of what it could look like:

One of the challenges is that security around hiring, background checks, etc., is usually an HR concern and not a CISO concern, but putting that aside, it’s clear that the technology can be built that reduces the problem of deepfakes. To me, the question is if that’s indeed the best way to solve the problem.

What if someone could reinvent the whole hiring experience, so that it’s simpler, better, more streamlined, more automated, and by default more secure? The buyer wouldn’t be a CISO but whoever owns the hiring process itself. I am sure someone is working on this, and I am not familiar enough with HR tech tools to say anything useful on this topic, but if someone is going to solve this emerging problem at its core, it’s likely not going to be a founder who builds “security for hiring”. It is more likely going to be a founder who builds a modern hiring experience that just happens to also be secure. The same can be said about deepfakes on Zoom, etc.

Failure mode: what makes companies that try to implement this approach fail

This story would not be complete if I didn’t briefly discuss one specific mistake that makes companies that try to implement this approach fail. I am talking about missing or misunderstanding incentives and trying to sell the solution to the wrong buyer.

To illustrate this point, let’s look at Chainguard. Here is their pitch: “Spend less time patching vulnerabilities and more time building software that innovates. Secure, CVE-free OSS that empowers teams to build the future instead of patch the past.”

The reason it works is that it talks to developers about the problems they care about: spending less time patching. Now imagine what would happen if Chainguard tried selling to developers a product that is supposed to make their container images more secure. I think I can guess the outcome pretty accurately - they would have failed because of misaligned incentives. Developers don’t care about security, so a product aimed at developers can’t pitch better security; it has to pitch what they care about (in this case, it’s not having to deal with security).

If, on the other hand, Chainguard tried to market to CISOs, they would probably also struggle since security teams aren’t the ones who feel the pain of having to patch container images (developers do). CISOs and security leaders can surely be champions of Chainguard, but it’s the CTO/Engineering organization that would be the buyer.

Getting the incentives right is very important because when selling something to other departments (IT, HR, operations, engineering, etc.), the value proposition cannot be about security, it has to be something they care about. We all wish everyone in the organization were incentivized to put security first, but the reality is that’s just not how it works. Developers want to develop, IT people want to deal with fewer issues, HR people want everyone to be happy, so anyone who tries to sell security to them instead of tools that make them successful in what they are measured on is not going to be met with much enthusiasm. Security has to be the inevitable side effect of solving some other, primary pain. As a side note, “shift left” is the most famous example of misaligned incentives, since forcing developers to run security scans in their workflow when their primary incentive is speed, not compliance, hasn’t gone too well.

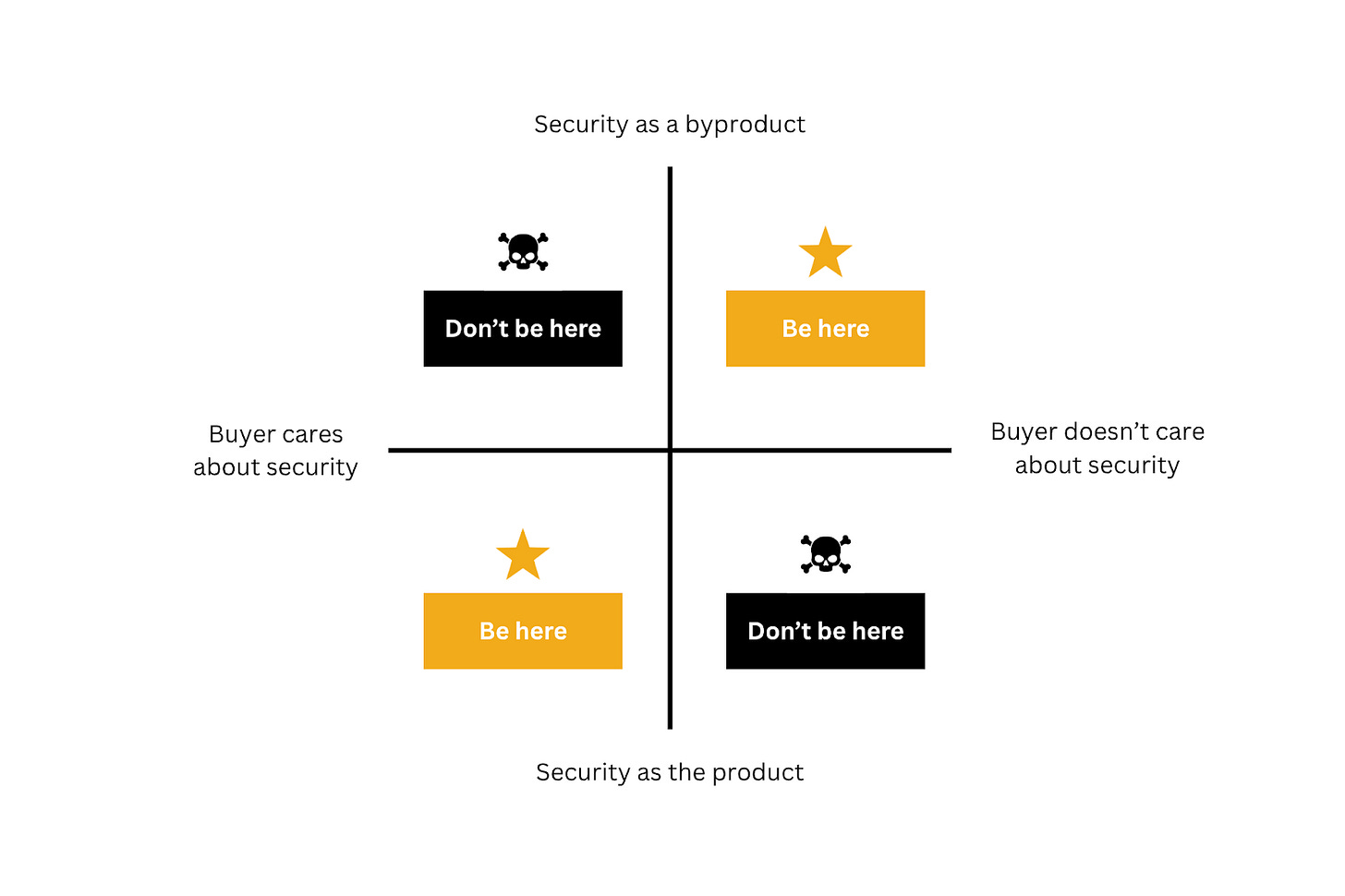

Here is a simplified way to summarize this: you want to either sell security as the product to the security buyer, or security as a byproduct to the non-security buyer. What you don’t want to do is to pitch security to people who aren’t incentivized to care about it, or to pitch non-security products to people whose job is to do security.