Three aspects of the cyber ecosystem I was wrong about not too long ago

An honest reflection on where my thinking has evolved

Over the past several years, I’ve learned a lot about our industry. A ton was learned by doing (though many readers of my blog know me through writing, I have always been and continue to be a builder and an operator before anything else), and an equal amount was learned by getting exposed to and seeing how things evolve outside of my immediate area of influence. This blog has kind of documented the evolution of my perspectives, and I will be the first to say that on some topics, this evolution has been pretty dramatic, and that much of my thinking today is very different from what it was a few years ago. To put it bluntly, I was completely wrong about way too many things. In today’s blog, I am going to discuss several of these things.

The CyberCEO Summit, held Dec 10 in Austin, TX, is where cybersecurity founders, CEOs, and investors come together to learn, connect, and shape the future of our industry. Hear directly from me and your fellow security innovators on scaling, funding, and navigating today’s market and GTM challenges. Meet 1x1 with security industry analysts, investors, influencers, and experts. This event is your chance to network with peers, gain actionable insights & feedback, and build relationships that can accelerate your company’s growth. Don’t miss the conversations that could define your next move or your company’s next big opportunity. CyberCEO Summit culminates in a VIP Founder, CEO, and Investor Dinner.

Cyber innovation doesn’t generally start in the Bay Area and then spread to other companies.

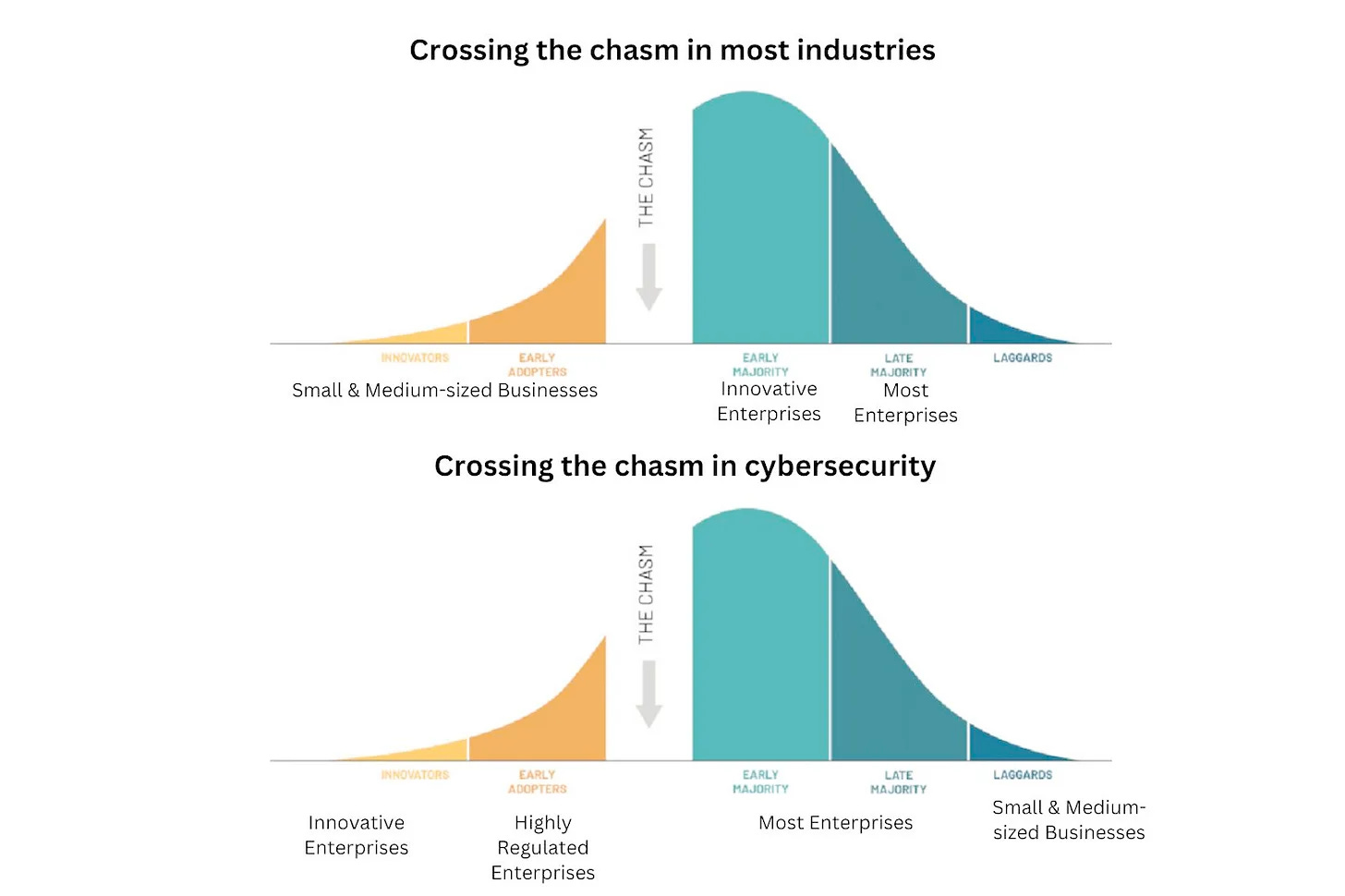

Many people assume innovation in cybersecurity follows a familiar pattern: new ideas start in the most tech-forward companies in the Bay Area and, over time, spread to the rest of the industry. The idea here is that engineering-driven, early-adopter organizations are the proving ground for security solutions, and everyone else eventually matures and follows (this is essentially the crossing the chasm model adapted to cyber). Others in security believe in the opposite path of starting with SMBs, proving the concept, and then moving up-market. That’s basically the whole idea of the innovator’s dilemma, meaning that large incumbents overlook emerging segments, and innovative startups win those markets, which over time allows them to disrupt the legacy players at the top.

Both concepts sound great in theory, and a few years ago, I thought they made sense, until I saw that in practice, neither really worked in cybersecurity.

I’ve previously shared the idea that in security, startups are faced with the inverted crossing the chasm problem. The way the story goes is that while in other industries SMBs are the first and large enterprises are the last to adopt new solutions, when it comes to security, the opposite is true. “In security,

Startups often first sell to the most sophisticated in terms of their security maturity enterprises (unless they choose to build their own solutions instead)

Then they reach out to enterprises in regulated industries (think of the challenges in tackling the hardest part of the market first!)

For most startups, this is where their market ends since most other companies are neither highly mature when it comes to their security, nor highly regulated, and hence they are fine with just buying well-understood solutions from incumbents. This is precisely the meaning of ‘crossing the chasm’ in cybersecurity.

The lucky few companies that reach the mass market become billion-dollar players.” - Source: Inverted crossing the chasm problem in cybersecurity: what founders and investors need to keep in mind.

I still believe, at a high level, what I wrote in that article with one important caveat: it really only applies to enterprises. Midmarket companies (and especially small organizations) have very different needs. In fact, the needs of businesses vary widely, and there are very few commonalities. The only security problem I can think of that’s truly universal is endpoint protection: no matter the size of the company, everyone uses similar laptops and desktops, and malware doesn’t discriminate based on the business size. Everything else varies dramatically.

A security product that’s a perfect fit for a tech startup in Utah would likely fail in a factory in Ohio, not because the factory is “less mature,” but because its problems are fundamentally different. The startup worries about SOC 2, data loss, and developer productivity; the factory’s top concern is keeping its machinery operational at all times. Some companies assume employees work remotely and believe the browser is the best place to enforce controls, while others operate in a world where that assumption makes no sense. Some treat their offices like “coffee shops,” with little emphasis on the network; others rely on their networks as critical infrastructure. Some treat workstations as disposable; others see them as the core of their operations and where security must live.

Every company is different, and these differences require different approaches to security and different security tools. The idea that somehow tech companies are “more mature” because they have broader needs is simply wrong. Startups that succeed in cyber are those that find a problem that a specific customer segment cares about, learn everything they can about that segment, and build a solution that works for them.

There are many ways to succeed. For example, Zscaler, Okta, and CrowdStrike all started by targeting enterprises, and it worked incredibly well for them. Okta had to eventually go downmarket because Microsoft owns the top of the market (check out Maya’s great deep dive), but solutions like Zscaler aren’t and will never be a fit for very small organizations. On the other hand, Vanta and Drata solved the problem of enabling startups to sell into enterprises, and there are plenty of organizations that won’t find them relevant for their custom compliance needs. That’s okay, too.

Pattern-matching in cyber is pretty hard because every company is different.

Pattern-matching in cybersecurity is really, really hard, and making sense of any trends is even harder. It’s tempting to think that we can spot trends and extrapolate them into the future to say with confidence that “the future of GRC is GRC engineering,” “every company is going multi-cloud,” or “cloud security will dominate budgets.” In practice, most of these generalizations about security are wrong, or at least wrong for the majority of companies.

One reason is that change in security isn’t just about technology; it’s about people and organizations. Technology can move quickly, but companies rarely adapt at the same pace, and so many predictions fail because they assume adoption will happen as fast as innovation. Take Zero Trust as an example: the concept has been around for more than a decade, there’s at least one talk about it at every conference, but many organizations still rely on VPNs and flat networks. If you want a more recent example, consider software supply chain security: after SolarWinds, it was declared “urgent and inevitable”, but years later, many companies still haven’t implemented code signing or SBOMs because process change is slow and painful.

Another reason why most predictions are wrong is that they are usually shaped by a very subjective context. Most reports we see are somehow associated with companies, and vendors base their worldview on the slice of the market they know best (their customers). A vendor selling to Fortune 100 banks will say “we talked to 100 CISOs and everyone is multi-cloud because of M&A,” but if your market is 50-500 employee SaaS companies that never do acquisitions, that “insight” is meaningless. Another example is when a developer-first tech firm warns that “securing the work of developers is the biggest gap,” but many retailers and manufacturers have other huge problems before they need to start caring about developers. Security leaders from Bay Area unicorns can say that “browser-native security is the future” because they live in a world of remote engineers, but a factory running air-gapped machines doesn’t care about Chrome extensions. These statements aren’t wrong, they’re just deeply context-specific, but too often presented as universal industry-level truth.

Maturity levels in cyber also vary wildly, even among organizations that look similar on paper. When you speak with twenty companies of the same size, in the same industry, with similar reporting structures, at least one will inevitably be experimenting with some advanced capabilities like AI security, while another is going to be rolling out multi-factor authentication. Security posture depends on leadership mindset, regulatory pressure, past incidents, and risk appetite as much as on industry or headcount. This makes broad trend-spotting super hard: the sample set for most reports can be wildly unrepresentative of where the market actually is.

All of this is to say that any kind of general statements about security are usually unreliable unless they’re anchored in a very specific context. Saying “everyone is doing X” often just means “everyone I know is doing X.” Founders should be skeptical of industry trends that don’t map to their actual customers’ reality, and they should build their thesis on lived experience and concrete customer archetypes rather than on abstract “market analysis”.

The only “good” segment to innovate in is the one where you have a meaningful advantage.

There was a time when I thought you could identify strong opportunities by simply understanding customer problems, doing deep user interviews, getting close to pain points, or staying ahead of market trends. I have since evolved my opinion about this. Now, don’t take me wrong: founders should still very much do all these things because they all result in learnings that can be incredibly helpful in avoiding obvious mistakes and improving the quality of their decisions. However, there’s no Holy Grail. These days, when someone asks me: “Is SIEM a good space to build in? What about third-party risk? Data backups?”, my answer is usually the same: “Go where you have a meaningful advantage.” Almost every corner of security can be reinvented. Everything in security is up for reinvention, and every problem can be solved better, differently, or more effectively, not simply with AI, but by approaching it from new angles. Whether it makes sense to build in a particular area depends on the experiences, insights, and unfair advantages the founders bring to the table.

Security in 2025 is really, really competitive. There isn’t a “great market” just waiting to be entered. No matter where you look, there are already plenty of players, and in a year, there will be more. The only great market is one where the founders have deep intuition and perspective. Data loss prevention? Great opportunity, if the founders know the space inside out. SIEM? Definitely lots of room to innovate, if the founders have real experience there. Application security? Same story. You can go from one segment to another, but the same thing applies everywhere: you can’t “user-interview” your way into a winning enterprise product. Customer discovery matters, but it’s not enough on its own. Founders need a solid footing to stand on, good intuition, lived experience, unique insight, distribution advantages, or a perspective others don’t have. In markets that aren’t as competitive (not sure what those are), founders can in theory come with little domain knowledge and be able to take time and learn before others catch up. In security, there is no such thing: the moment one person has an idea, there are 10 companies trying to do the same. Advantages translate into speed of execution so those that have more of them, often win.

In the end, regardless of which market you pick to build in, it’s either going to already be crowded or it will become crowded the moment someone finds an angle that ends up working. I think founders should bet on themselves, their expertise, and their ability to figure things out because that’s generally achievable. What is much more rare is the ability to predict the future or to be smarter than everyone else, so I think it’s better not to bet on that.

Closing thoughts

I started this post by saying that there’s a lot I have been wrong about, and I know for a fact that the list of topics where I’ve evolved my thinking goes far beyond what’s in this article. Venture in Security has been my way to share my thoughts and to learn in public, fully knowing that a lot of my thoughts will evolve. I treat that as a constant evolution. As Winston Churchill said, “Those who never change their minds, never change anything”.

Innovation isn’t about spotting the next hot label. It’s about standing where no one else bothers to look, and moving before they realize it’s ground worth fighting for.

By the time the market names the “trend”, the game is already finished.

And the reminder security keeps teaching: attackers don’t read your job descriptions.

Really interesting read.