There are four ways to compete as a security platform

In this piece, I zoom in on security platforms and discuss four ways in which they can compete.

When we talk about cybersecurity platforms, it’s tempting to assume that there is only one way to compete, namely going head-to-head against everyone else in the same market. This is simply not the case.

In one of my previous posts, I explained that point product vs. platform is not the right way of looking at things, and instead, there are four buckets that come into play: best in class point products, best in class platforms, good enough point products, and good enough platforms. I have also explained that most successful point products are “best in class”, and most platforms are “good enough”.

In this piece, I zoom in on security platforms and discuss four ways in which they can compete. Needless to say, there are plenty of other equally valid ways to segment security platforms, and the idea presented in the article is just one of them.

This issue is brought to you by… Wiz.

2024 Gartner Market Guide for CNAPP

Why are leaders are increasingly adopting a CNAPP to transform their cloud security operations?

This guide reveals strategic recommendations and the growing need for a comprehensive platform with breadth and depth of functionality.

Read the report to learn:

The benefits of a CNAPP solution in your cloud security strategy

Key capabilities and characteristics to look for in a CNAPP

Recommendations for how you should approach a CNAPP evaluation and deployment

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

It’s too hard to wage wars on all fronts

In order for companies to succeed, they need to maintain focus. This doesn’t just apply to early-stage startups; large platform players also operate under the constraint of limited resources even if they have much more resources than someone at seed stage. No company can do it all, solve all problems, support all use cases, and make everyone happy. Those who try will inevitably spread themselves too thin and lose their competitive edge.

Smart security founders have clarity about who they compete with, and along which criteria. Broadly speaking, there are four ways platforms in our industry can compete:

Security platforms that consolidate existing point solutions.

Security platforms that compete based on a specific use case.

Security platforms that serve a specific type of buyer.

Security platforms that compete with other platforms head-to-head.

Four ways to compete as a security platform: a closer look

Security platforms that consolidate existing point solutions

A common way in which platforms compete is by consolidating the existing point solutions. This happens when there are many point products that are complementary to one another, but there is no single, all-in-one offering. Such inefficiency forces customers to assemble stacks of disjoint solutions and therefore creates an opportunity for innovation.

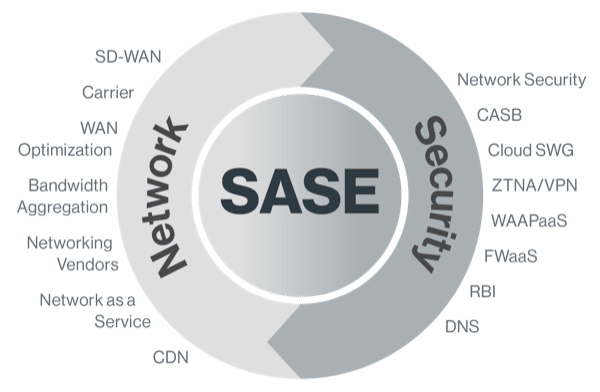

Once upon a time, this was exactly the story of Security Access Service Edge (SASE) but by 2024, the category has fully consolidated.

Source: Cato Networks

Today, as my friend Elad Erez insightfully notes, it is highly likely that we are seeing an emergence of a new consolidated category, Continuous Threat Exposure Management (CTEM). Breach and attack simulation (BAS), continuous pentesting, vulnerability management, asset management, and a long list of other solutions are all merging into one category. I am sure there are other examples of consolidation that are happening on the market (feel free to hit “reply” and share what you think these are), but this one seems pretty obvious.

Players attempting to consolidate existing point solutions have a list of challenges to overcome:

They need to pick an initial wedge that will allow them to get to market quickly, prove their hypotheses, and start growing.

After solving the initial problem, they need to expand into new areas. The timing for the expansion has to be flawless: not too late so that it can capture as much of the market as possible, but also not too early so that it can establish itself as a leader in some area first. If a startup spreads itself too thin too early, it will likely fail. If, however, it moves too slow, it will likely get outcompeted by rivals that move much faster. Timing is everything.

Security startups that compete by consolidating point solutions, usually align their value proposition with one or more of the following:

Simplifying the security stack and achieving increased efficiency. Security teams forced to cobble together multiple separate tools know that more products means more purchasing and vendor management complexity, more situations when products don’t talk to one another easily, more risk that some of the security building blocks will fail or get acquired, more complex architecture, and subsequently, an expanded attack surface. Buying a solution that brings multiple components together in a unified platform can address several problems at once.

Cost savings. Fewer vendors means that buyers can negotiate bundled pricing and volume discounts with platform players, thus reducing the cost of security tooling. This, combined with the reduction in overhead needed to keep multiple products up to date, can result in significant cost savings. It’s worth noting that consolidating multiple use cases with a single vendor can also lead to increased costs in the long term due to vendor lock-in.

Security platforms that compete based on a specific use case

Another way in which security platforms compete is based on a specific use case. This is most commonly seen in areas that already have a set of established platform players. A good example is the Secure Access Service Edge (SASE) market. What started as a collection of SD-WAN, CASB, SWG, [ …? ], has now evolved into a mature category referred to as SASE. In 2024, any vendor thinking about competing as a SASE is faced with a tough choice: drown in competition by positioning itself as yet another SASE, or pick a market segment that doesn’t need the bells and whistles of the full-fledged SASE, and identify a specific set of use cases where it could offer a valuable solution. Such a company would also need to:

Make sure that the market for this initial set of use cases is big enough to get started and capture some market share.

Identify what an initial winning bundle could look like.

Ensure that the entry point is defined in a way that provides a path for a larger vision and more innovation.

Instead of positioning itself as yet another SASE play, the company could pick a well-defined use case (access for third parties, access for remote employees, access for SaaS applications, etc.) and start by firmly establishing itself as a leader in that space.

A great example of security startups that compete based on a specific use case are enterprise browsers and browser security extensions. Companies in these segments understand that it’s easier to get their tooling adopted as a replacement for virtual desktop infrastructure (VDI) or as a great way to support bring your own device (BYOD) policy. Although deployment sizes for this specific use case may be small, startups are using the offshore workers and contractors use case as a Trojan horse to then hopefully expand their deployment company-wide.

Security platforms that serve a specific type of buyer

Another common way for security platforms to compete is to choose a specific type of buyer. There are four main dimensions:

Geography. A company may choose to position its platform for a certain region that is underserved by its competitors. For example, it could build a tool tailored to companies in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa (EMEA) instead of the US market where most security players focus their efforts.

Market segment. A company may decide to focus on a specific market segment. For example, it could build a platform for small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) instead of going after the large enterprises as everyone else is trying to. A good example of this strategy is Todyl - a security startup that offers a long list of capabilities delivered via a single agent, and targeting small and mid-sized businesses. Another company that embraces a similar mindset is Huntress.

Buyer persona. Most people assume that CISOs are the only buyers of security products. This isn’t the case. While many types of end users do indeed report to CISOs and rely on enterprise security budgets (application security teams, cloud security teams, network security teams, IT, and the like), we have seen that security solutions can also be sold to other personas such as virtual CISOs or even go-to-market teams (although I am not sure who teh buyer is in case of the latter).

Industry. In the past, industry-focused companies were generally only found in the services space. In the past several years, however, we have started to see a growing number of product startups built exclusively to serve specific industries. Most commonly we see this with highly regulated and compliance-heavy industries such as healthcare but I am confident we will start seeing these pop up in other parts of the market as well.

Security platforms that compete with other platforms head-to-head

Although going head-to-head against other platforms isn’t what we see very often, is it indeed one of the ways in which companies in cybersecurity can compete.

There are many factors that could create an entry point, for example:

A competitive platform is not yet viewed by the market as a leading or established player.

A competitive platform is struggling with execution.

A competitive platform is expensive and a path exists to offer a similar set of capabilities at a lower price which the rival cannot easily pursue due to technical, business, or other reasons.

A competitive platform is significantly inferior in some way that matters as a buying criteria (user experience, implementation complexity, total cost of ownership, etc.) and it doesn’t have a way to easily close the gap.

A competitive platform isn’t great at solving problems for a specific market segment, thus creating opportunities competitors can take advantage of.

There is a better way to solve the problem but the competitive platform is too deep into pursuing their old way.

Right now, we are seeing this play happen in the AI security space where several solutions are going head-to-head against one another as platforms.

An interesting case where an opportunity could exist to compete with an established security platform is when there is a fundamental change in technology (think of companies moving to the cloud or adopting AI) or when an old way of doing things is leaving a security gap that must be closed to avoid potentially catastrophic consequences. A good example of the latter was the need for behavioral detection which enabled CrowdStrike to create an endpoint detection & response category. Since established platforms the startup would be going up against usually have the advantage of credibility, trust, economies of scale, and distribution channels, in order to stand the chance to even be evaluated during the proof of concept (POC), a new company has to be much better along some criteria that matters.

I have observed that most commonly, platforms that compete with other platforms head-to-head are seen in highly commoditized markets. It’s hard to say if it’s a correlation or causation since it also makes sense that any market where there are several players offering the same undifferentiated solutions, would turn into a commodity.

Becoming a security platform isn’t always as great as some people assume

There is a common assumption in our industry that becoming a platform is the ultimate Holy Grail for any company. Sadly, it’s not quite the case, and the reality of the market is much more nuanced and complex.

Security platforms have a hard time positioning and differentiating against competition

First and foremost, platforms have a hard time positioning and differentiating against competition. The broader the platform, the harder it is to explain what makes it unique, and what problems it can solve better than its rivals. The more features the platform offers, the more watered down its marketing message becomes. Moreover, lack of focus results in complicated, hard-to-understand, configure and maintain products. This results in low customer satisfaction and has the potential to increase churn.

Security platforms have a hard time getting to an exit

Anyone who has been observing the security startup space long enough to see at least one generation of companies get to an exit knows that point solutions are much more likely to get acquired than their platform counterparts. This is the case for several reasons:

Acquirers are often looking to add best of breed complementary products to their portfolios. When point products start adding adjacent capabilities, the quality of these new areas is likely to be lower compared to the initial product.

Companies building point products are usually earlier on their journey (pre-Series B or C) so they would have raised less capital and therefore their valuation (and subsequently their potential acquisition price) is much lower.

Integrating a point solution with a security platform is much easier than marrying two large and complex platforms. In the case of the former, it is much harder to achieve a unified experience and do it in a way that scales.

All this is also why, as I have stated before, most security startups are better off getting acquired before Series B. When a company crosses that milestone, the market starts to evaluate it as a business (revenue, growth rate, etc.), and not as a feature that could be complementary to an established platform and therefore a good acquisition target.

Not every security platform becomes a platform by choice

If most security startups are better off getting acquired before Series B, why are so many chasing the dream of becoming a platform? There is no one answer. Some legitimately have solid growth potential, and a large market, and their founders have what it takes to go all the way to IPO. Others may be overly optimistic and assume that simply having a feature-rich product will be enough for them to go public. That said, I think the majority of security startups turn into platforms without much thought and almost on autopilot. This happens because they don’t have a choice.

Some companies building point solutions are indeed lucky to get lucrative acquisition offers. Sadly, that doesn’t happen to everyone, and most startups are forced by the market (and their investors) to keep growing, adding new capabilities, and expanding into adjacent areas which slowly turns them into a platform. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but the longer they operate and the more capital they raise, the less choice they have about becoming a platform.

Point solutions that get to later stages without expanding into larger platforms usually exhaust their total addressable market and get outcompeted by their rivals. Since the market is always in the process of consolidation, remaining focused on a single use case as the company progresses can easily become a death sentence. Too many startups get stuck in this predicament, without any ability to exit, and without any vision (or hope) to ever grow into their valuation as a platform.