The real dilemmas of cybersecurity startup ideation, discovery, and validation

Sharing some lessons learned about startup ideation

Over the past several months, as I was working to flesh out the problem space my co-founder and I are going after, and the specific problem we are looking to solve, I spent a lot of time going through the startup ideation, discovery, and validation. On this journey, I learned several things that I think will be helpful for other founders. In this piece, I am going to share some of these learnings.

Specifically, I am discussing dilemmas with cybersecurity startup ideation, discovery, and validation.

This issue is brought to you by… Vanta

Virtual Event: AI-Powered Risk Management with Vanta

Risk isn’t just growing—it’s spreading across more systems and vendors than ever before. Security gaps, compliance demands, and vendor dependencies can put your customers, reputation, and revenue at risk. For GRC teams relying on traditional tools and manual processes, the workload is quickly becoming unsustainable.

This Vanta Delivers session introduces new AI workflows to centralize risk management, cut manual work, and strengthen security—all while enabling faster collaboration. Join the virtual event and learn from leaders at Anthropic, Arcadia, and Vanta about:

Automating policy drafts, bulk updates, and evidence gap detection

Saving time with continuous monitoring and Slack integrations

Proactively managing compliance and vendor risks with AI

First, some background

In December last year, I wrote an article titled “Let’s have an honest conversation about the state of cybersecurity”. In that piece, I explained several fundamental truths of our industry. Before we dive into the dilemmas with startup ideation, it’s very helpful to discuss a few ideas I covered in that article because they are foundational for what we’re going to be talking about here.

We like to repeat a blanket statement that security should be top priority for every organization, but the reality is that it’s objectively not equally important for all kinds of companies. For example,

For companies in highly regulated industries such as insurance and financial services, being able to meet compliance requirements is quite literally an existential problem. If they cannot prove to the auditors that they are compliant, they might not be allowed to stay in business. This is a huge deal.

For companies in the technology sector, security and compliance are critical sales enablement instruments. This makes sense since tech companies need to make sure customers are comfortable sharing their data or embedding the companies’ software into their organizations. To them, cybersecurity is a core attribute of the product they are selling. Without SOC 2 attestation, multi-factor authentication, and a variety of other attributes, a technology company literally can’t sell to the most lucrative types of customers (large enterprises). This is also a very big deal.

For companies in most other industries, security is a way to prevent losses and stay operational. Most businesses aren’t highly regulated, and their customers have no reason to treat security as one of the top 10 things they care about. When a customer is ordering a new coffee machine, a sofa, or a container of coal, they have no real reason to care about the security posture of the supplier (as long as they can contractually guarantee the delivery of the products, that is). This is why most companies out there have much less incentive to invest in security than we’d like.

These ideas aren’t groundbreaking, but it's important to start here because it makes it easier to understand what I call “the great cybersecurity echo chamber”. When you think about who is active on social media, who writes blogs (such as this one), who records security podcasts, who gives talks at security events, who launches security startups, who security vendors are most excited to talk to, who VCs want to spend time with, etc., they are all the same people. They either work at organizations where security is a revenue enabler (tech companies, large banks, etc.), build or work at security startups, are aspiring founders, or investors. There are surely a handful of outliers, but by and large, it is all the same group of people.

As I explained in my December article, “I am calling it an echo chamber in the kindest possible way (after all, I am very much a part of that echo chamber whether I like it or not). The fact that most perspectives people read online seem to only be relevant to a small percentage of the engineering-centered companies isn’t a problem. The problem is in thinking that these perspectives represent the industry as a whole. The reality is that they don’t, and that a lot of what we are discussing simply isn’t relevant to a large percentage of the security teams out there”.

“The great cybersecurity echo chamber” and startup ideation

When aspiring founders are thinking of building a new security product, many want to do the right thing and validate if what they’re thinking of building is going to solve real-world problems customers care about and will pay for solving. The problem is that this is exactly where the echo chamber effect kicks in. Let me explain.

The vast majority of CISOs have never been to RSAC or Black Hat, and of those who did, many haven’t been back for a while. Moreover, most CISOs have never been on a podcast, never been an advisor to a cyber startup, and probably never been a part of a VC CISO network. Furthermore, most CISOs aren’t actively sharing their insights on social media or in their personal blogs. The CISOs that don’t do these things (which I’d say are 98-99% of all CISOs), aren’t simply ignoring the cyber community. On the contrary, they may be pretty active on a peer-to-peer basis, but they are just not as visible. Not for any particular reason except for the lack of time, interest, or too many other commitments. Some are raising three kids, others are caring for their relatives, and some may even have other career aspirations. After all, CISOs are just regular humans.

Because these 98-99% of CISOs are pretty hard to reach, founders naturally gravitate towards the 1-2% who are visible in the community - as social media influencers, startup and VC advisors, angel investors, frequent podcast guests, conference organizers, and so on. In other words, founders reach out to VCs who are “plugged in” into the cyber ecosystem because they are, well, a part of the same community. This precisely is the dilemma. There are many reasons why talking to CISOs who are exposed to the startup community is a great thing. First, they see a lot of startups, so they are pretty attuned to the market, what innovations are being built, etc. Second, as innovators and startup enthusiasts, they are the most open to trying new ideas, becoming design partners to startups, and helping companies shape their go-to-market efforts. They usually have a great perspective to offer, and founders looking to validate their ideas should most definitely be reaching out to them.

At the same time, it’s too easy to forget that 1% of something is still just 1%. When everyone is asking the same people the same questions, they get the same answers, and they all end up building the same products. When you see that this is what’s happening in cyber, you can’t unsee it.

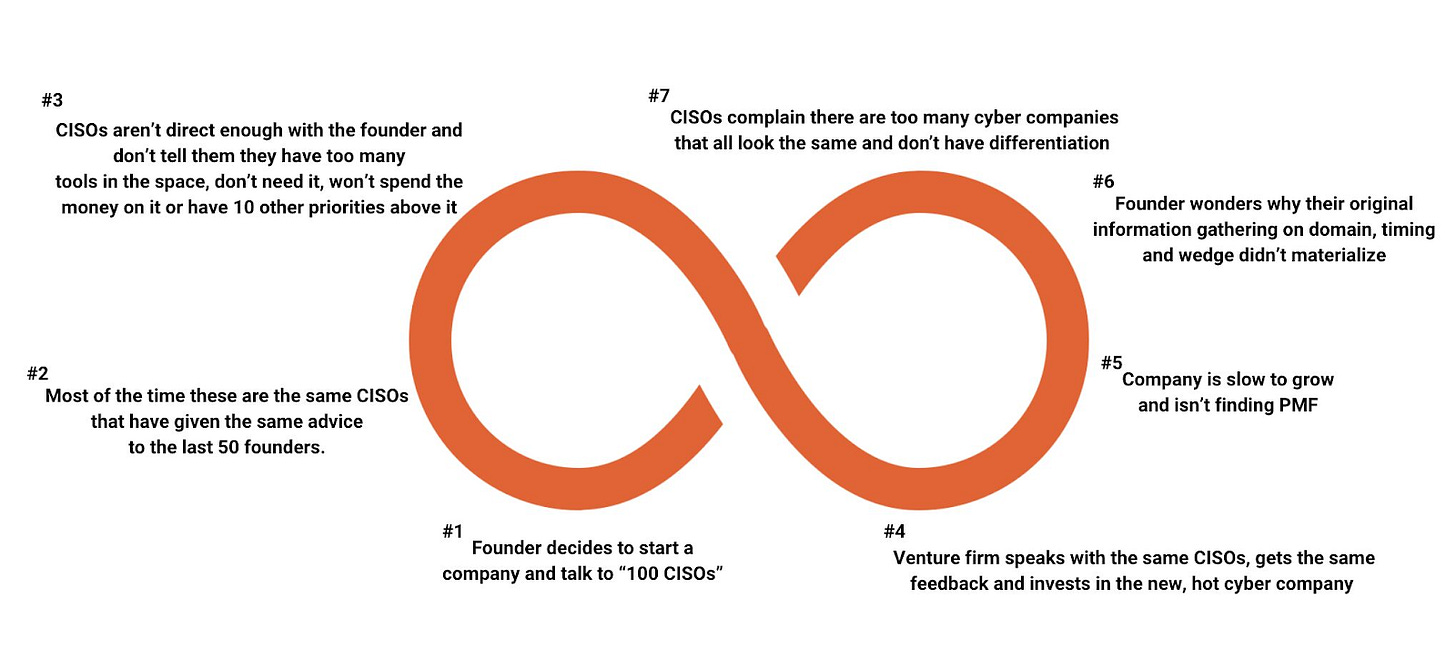

A week ago, when I was doing the research to see if someone else had written something about this problem, I came across a post from Stephen Ward. Not only he had articulated the problem better than I ever could, but he also shared a picture that illustrates this better than anything else I had in mind.

Image source: Stephen Ward

The closed loop of cyber ideation

Stephen’s diagram hits the nail on the head. In cyber, most startup journeys begin in a similar way: a founder decides to “talk to 100 CISOs” before building. In practice, most of those conversations are with the same group of CISOs - industry veterans who have already given nearly identical feedback to dozens of other founders. Nobody can blame CISOs for doing it because, at the end of the day, they are being asked the same questions over and over, so most of the time (unless founders get them on a bad day), they’ll give the same answers.

Because CISOs rarely want to shut down an eager founder directly, the feedback tends to stay polite: “This could be useful” or “I’d want to see it integrated with what we already use.” What doesn’t get said is often more important - that budgets are already locked up, that similar tools are gathering dust, or that solving the problem isn’t anywhere near the top of the priority list. Founders hear encouragement where there should have been disqualification.

Investors step into the same trap. They go back to those same CISOs for validation, hear the same cautiously positive signals, and assume there’s real demand. The result is that we see another round of funding for yet another startup that looks and feels like the last ten. Growth slows, PMF never arrives, and everyone wonders why the “CISO validation” didn’t translate into traction. If you think that somehow the AI wave is different, it’s not.

This cycle has created an industry crowded with nearly indistinguishable products. This is not happening because founders lack creativity, or because CISOs aren’t being truthful. The validation loop itself is broken, and I genuinely hope that more founders look at Stephen’s image and look for ways to break that loop. As long as founders keep chasing consensus from the same sources, they’ll keep building companies that blend together. Breaking out of the loop requires contrarian insight, sharper disqualification, and the courage to listen for the “no’s” that don’t get spoken. More importantly, this requires not being afraid to do the hard work and to try doing different things differently.

Breaking away from the default pattern

I’ve been through this ideation and validation journey not too long ago, and I’ll be the first one to say that breaking away from the default pattern is anything but easy.

First, we can’t forget about the reasons why we run into these problems to begin with. The majority of the CISOs aren’t a part of the startup ecosystem; they are hard to reach for most founders, and most wouldn’t be able to convince their company to work with a startup.

All that said, startup founders do need to do things differently if they want to get different results. In his post, Stephen gives founders five steps to follow:

“1. Talk to folks deeper in the org. Head of security engineer or ops. Head of IAM, etc.

2. Dig for priorities, not just problems. What will actually get budget over the next few years?

3. Don’t confuse politeness with purchase intent.

4. Challenge your wedge and timing assumptions every quarter.

5. And please — differentiate with something that is deeper tech.”

I agree with every bit of this. I’d even go deeper and say that it’s very helpful to understand the problems of the end users, not just directors. Not every end-user pain will translate into solutions the company will buy, but without understanding what the end users are going through in their day-to-day, any product will be at best a leadership-level tool. The company may buy and implement it top-down, but when the time comes to renew, if nobody is using it, it’ll not go well for the startup. CISO is an economical buyer, not a product feedback center. To get ideas and product feedback, founders need to go to practitioners.

At the same time, there is a cautionary tale about talking to customers that we just released today - a podcast with the founder of Zscaler, Jay Chaudhry. Jay shared his story of talking to customers in the early days and concluded that while it’s important, founders shouldn’t rely on customer feedback too much when they are building something disruptive. Talking about incremental improvements is very helpful, but most customers won’t be excited about disruptive tech, as was the case for Zscaler.

The other aspect I’d emphasize is the importance of trying to reach people who aren’t deeply immersed in the startup ecosystem. Several VCs are fortunate to have built strong networks, but if you aren’t a founder who raised from such a VC, you still have options. What has worked for us is reaching out to friends and friends of friends and asking for many, many, many favors. It always takes time to figure out the ideal customer profile, the right language, etc., but if you keep going at it, eventually you’ll succeed. I know because that’s what I did not that long ago. There are a few reasons why you want to reach out to people who aren’t deeply immersed in the startup ecosystem. First, they have a different perspective, and you need that variety to actually understand the market, the customers you are going after, etc. Second, you may be surprised to learn that they have a very different take on the problem you want to solve, and what resonates with startup-connected CISOs doesn’t resonate with them, or vice versa.

Taking contrarian bets gets easier if you find a way to talk to people others aren’t talking to

This is something I’ve learned in my own experience: taking contrarian bets gets easier if you find a way to talk to people others aren’t talking to. I think when you look around yourself and see where all the attention is going, you can take one of the two stances. One is to say, “because everyone is building an AI SOC, an identity graph, AI pentesting, [ insert your favorite idea here ], I should also do one of these”. Or, you can say, “because everyone is building an AI SOC, an identity graph, AI pentesting, [ insert your favorite idea here ], I am not going to be building one of these”. Both are valid decisions, both have their pros and cons, and both can lead to good and bad outcomes.

History will be the judge over which path is going to yield better results. What I can say now with certainty is that it’s much, much easier to do different things if you find a way to talk to people who care about (and are willing to pay for) solving different problems. Oftentimes, the only way to do that is to get outside of what I call the “great cybersecurity echo chamber” (of which I am most definitely a part). To take a contrarian bet, you have to know what others don’t, and the only way to do that is to either ask totally new questions (it’s hard to be this creative) or to talk to different people (this is harder but also easier).

The importance of building in the space where you have the right to win

One last note I wanted to share on the topic of picking an idea is simple: go where there is an intersection of what you’re great at and what the world needs. There are plenty of stories of cyber founders who ended up becoming very successful in the space they knew nothing about when they started. That will not change since there will always be these cases when people just figure things out. All that said, given how competitive security is today, and given how much easier AI has made it to learn the basics of new domains, I believe there are only three real moats left: domain expertise, technical complexity, and speed of execution.

In the world of AI, domain expertise is probably your last defensible edge (Michelle Moon has a great article on this topic, and I highly suggest reading it). It is really hard to “user interview” your way into a solid insight. To build something differentiated, something of real value, founders need to have a perspective, an intuition, and some depth, and all that only comes with real experience.

Today, most products sound the same - it’s a variation of “give us your data and we’ll build a graph”, or “we’ll integrate with these 10 APIs and automate your workflows”. When everyone is building with cloud APIs, there is no real differentiation - it just comes down to execution. To achieve real differentiation and to build a lasting company, it helps to go where complexity is and embrace that complexity. As I explained recently, the best tech moats come from solving the hard problems. Some challenges are so brutal to execute that very few teams even attempt them, and those who succeed gain a durable advantage. For example:

Being in the path of the network is hard. Building a global proxy infrastructure with distributed points of presence is expensive, complex, and latency-sensitive, yet Zscaler pulled it off and dominates.

Living on the endpoint is hard. OS fragmentation, constant kernel changes, and finicky update chains make agents a nightmare to maintain, yet CrowdStrike and SentinelOne turned this into an enduring moat.

Building a browser is hard. Chromium alone is 32M+ lines of code, with relentless update cycles and web compatibility headaches, yet Island, Talon, and Surf are doing great.

Tracking data lineage is hard. Data moves in countless ways, across hundreds of storage and compute environments, yet Cyberhaven made it a defensible business.

When a problem is painful enough that most founding teams avoid it, that pain becomes the barrier. If you can push through, the moat is built into the difficulty. All this is only possible when you have domain expertise. Neither Zscaler nor CrowdStrike agent, for example, would have easily been built by generalist full-stack devs and a founder who interviewed a few CISOs and heard about a problem.

Lastly, speed of execution is also a factor of domain expertise. CrowdStrike founders had experience in endpoint, Zscaler founder in network, Island founders in browser, and so on. People these days love to bring up Wiz as an example of literally everything, so it’s fitting to remember that the Wiz founders have spent over 8 (!) years in cloud security before they started Wiz. During these eight years, they started Adallom, exited it to Microsoft, and then spent years at Microsoft running cloud security.

Domain expertise, technical complexity, and speed of execution are the last three moats left, and the latter two are derivative of domain expertise.