Stop comparing safety and cybersecurity, they have very little in common

And it’s time to put the seatbelts analogy to rest

Nearly a year ago, we hosted Dug Song, the legendary founder of Duo Security, on Inside the Network. During that conversation, Dug shared a powerful analogy that has stuck with me. He explained that in aviation, a plane crashes the same way only once, or maybe twice. Whenever it happens, we get to the bottom of the failure by analyzing black boxes, and then the entire systems and plane designs change to prevent the same failure from ever happening again. In security, it’s a different story. Organizations get breached the same way over and over, and oftentimes the same company gets breached for the same reason many times. Dug described this as a “Groundhog Day in the worst possible sense”, a hamster wheel of pain where we’re not actually getting better, just reliving the same incidents again and again.

This issue is brought to you by… Prophet AI.

The Economic Fix for the SOC: AI-Driven Autonomy with Human Guidance

Security leaders know current SOC unit economics are unsustainable. Hiring more analysts cannot scale to meet the volume of modern alerts, and legacy automation tools are often too rigid to maintain. Prophet Security offers a different path: AI-driven autonomy that elevates the role of the SOC analyst.

Prophet AI functions as a virtual SOC analyst, autonomously investigating alerts with the same depth, quality, accuracy, and transparency as your best SOC analysts. By handling the high-volume investigative grunt work, Prophet AI allows you to transform your SOC operations from one where analysts are consumed by repetitive tasks to one where they can focus on high-impact, low-volume AI-validation, threat hunting, or detection engineering.

I think most of us feel Dug’s pain, and, unfortunately, we have to go through this Groundhog Day what feels like every single week. I most definitely agree with the sentiment Dug expressed, but I don’t agree with the analogy. It took me a while to realize why that is the case, so in this issue, I am talking about reasons why it doesn’t make any sense to draw parallels between safety and security.

The well-loved seatbelts analogy is sadly not relevant

People in security absolutely love to bring up the story of how seatbelts redefined road safety (if you’re not sure what I am talking about, here’s an example of how CISA compares its Secure by Design Pledge to the initiatives in the automotive and aviation industries).

The story goes like this. As the car adoption in the US increased in the 1950s-1960s, the number of road fatalities skyrocketed. It soon became clear that the mortality could be greatly reduced by adding safety features to cars, but making it happen wasn’t easy. First and foremost, car manufacturers, including GM and Ford, heavily lobbied against mandatory seatbelts and safety regulations, arguing they were expensive and unnecessary. Drivers, on their part, also weren’t excited about seatbelts because they made them feel uncomfortable. In the end, common sense prevailed, and in 1966-1968, a series of laws were passed that started requiring seatbelts to be installed in all new cars. It was, however, only in 1984 that New York enacted the first mandatory seatbelt usage law. By the end of the 1990s, almost all states made wearing seatbelts mandatory, and today we take seatbelts for granted, thinking that’s how things have always been.

The idea that we can do something similar with security, and have the government legislate everyone to become “cybersecure,” is appealing, as are all sorts of pledges. It would indeed be great if we didn’t have to reinvent the wheel in security, and instead we could borrow from other fields and learn from past successes. Unfortunately, this is quite unlikely to work, and the main reason is pretty simple: safety and security are two very different problems.

Safety and security are two very different problems

Safety addresses a stable, unchanging problem, but security doesn’t

First and foremost, safety controls address a stable, unchanging problem. Let’s take our favorite seatbelts as an example. Seatbelts were designed to address a very specific, very well-defined risk: injury or death during a car crash. There are a finite number of things that need to be considered and tested (things like speed, impact angle, where the passenger is sitting, how tall the car is, etc.). I am not suggesting that accounting for all these factors is easy, but the critical point here is that gravity doesn’t learn or change its methods. The physics are stable, we know pretty well how things are supposed to work, and if we recreate the same environment (which is easy because of the limited number of factors that need to be considered), we’ll get the same result.

Cybersecurity, on the other hand, is nothing like that. Attackers try different methods until something finally works, adapt their tactics, and purposefully look for gaps in security controls. My friend Luigi Lenguito, founder of BforeAI, puts it really well in one of his LinkedIn comments: “Many keep equating security and safety, but they are two very different problems. Safety is finding the root cause, fixing it, and having a safer environment with a tendency toward zero accidents. Security is putting controls and remediation, but meanwhile, new risks arise, so it does not tend to zero because the adversary is motivated to increase the harm and impact. It’s a non-controlled environment.” Basically, wearing a seatbelt won’t trigger a new kind of crash, but a security control often does trigger a new attack path.

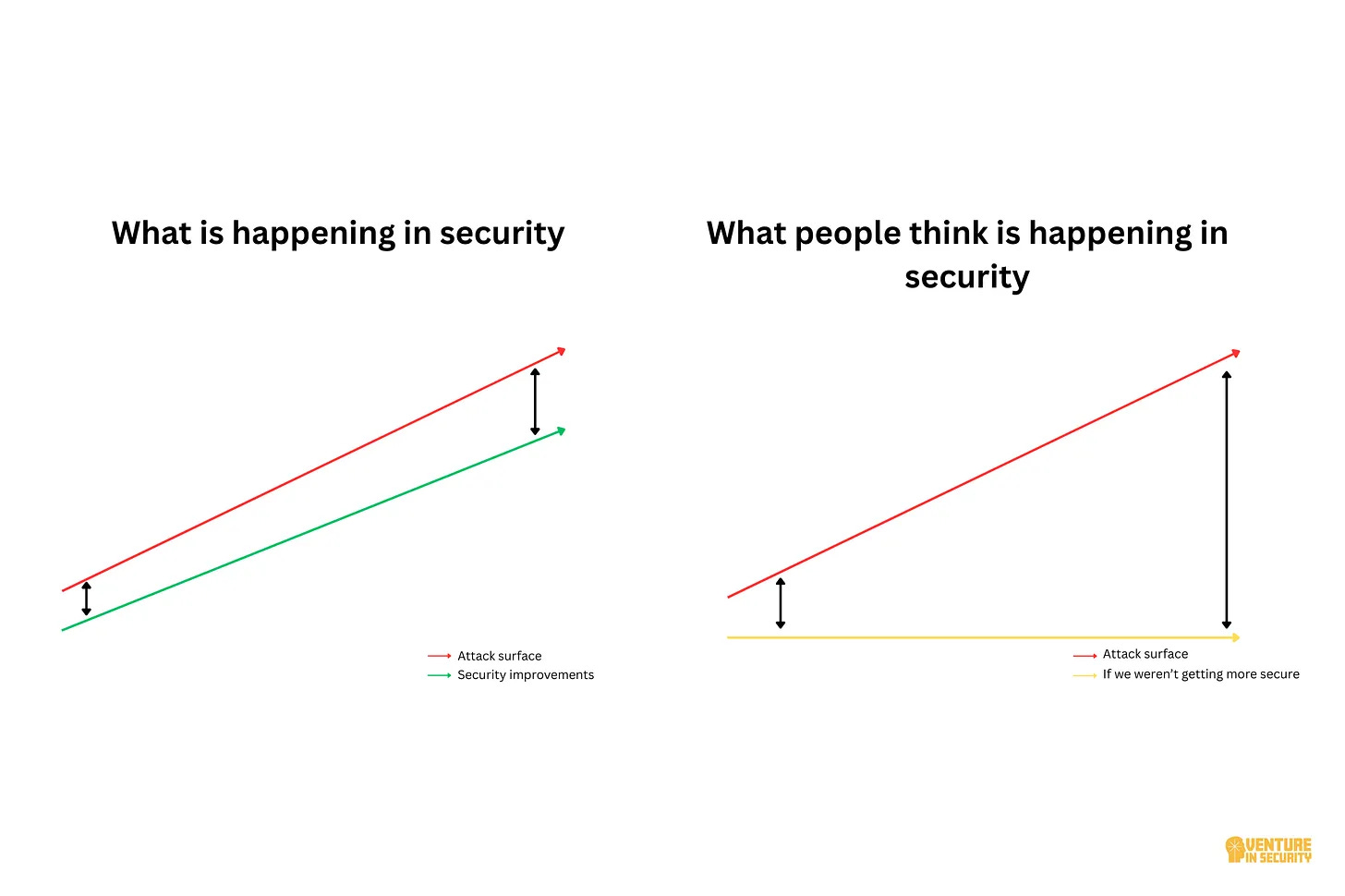

I published a relevant deep dive a few weeks ago about how we are actually improving our security maturity, but it’s hard to see that because attackers are also improving their methods: If you ask these two questions, you’re asking the wrong thing. This is precisely the problem as attackers continue to adapt to the controls we put in place.

Image Source: If you ask these two questions, you’re asking the wrong thing

Safety prevents loss of human life and injuries, but most cybersecurity controls don’t

An equally important distinction between safety and cybersecurity is what’s at stake.

When it comes to safety, the concerns usually have to do with human life, or at least well-being. The reason why we spend so much time getting to the root causes of a plane crash is because of how catastrophic and devastating it usually is. We care about car safety, food safety, building codes, etc., for the same reason - because there is a long track record of people getting physically harmed or losing what we as a society can (mostly) agree is the most precious gift we all have, our lives.

Cybersecurity is thankfully not usually a matter of life and death. Despite all the bleak predictions and despite the fact that attackers could very well cause massive loss of human lives, the majority of cyber attacks have been financially motivated. There have, sadly, also been cases when people would get harmed because of ransomware attacks on hospitals, but (again, thankfully) it has not yet become as widespread as some predicted. Not only have most people not heard of the major security breaches, but the vast majority of the population haven’t felt any pain when their own data gets leaked. Here are some of the ways in which an average individual gets affected by security- and privacy-related concerns:

Someone gains access to their email address and uses it to send spam. While this definitely creates inconvenience, it doesn’t usually lead to irreparable harm to the victims.

Clicking on some link installs adware on the victim’s computer. In practical terms, this means that once in a while, a person will see some annoying message pop up in the bottom right corner that they will need to close. It’s inconvenient but not deadly.

It is not uncommon for people to have their credit card data compromised, which typically leads to fraudulent charges on their bank accounts. I had that happen several times to me as well; in each of those cases, the bank will typically issue a new card and refund the lost amount.

I am not trying to underestimate the impact of security incidents on people’s lives. There are indeed cases when families lose all the savings it took them decades to accumulate, and private details of one’s life get leaked, causing irreparable harm and even a loss of life. However, most people think of these stories as anomalies, not something that can affect them personally. It is hard to blame people for this lack of awareness. Although our data is sold for pennies on the dark web, most people never feel the impact of the Uber or Equifax hacks beyond getting a breach notification email and some free identity monitoring solutions that most don’t understand the value of.

Basically, to most individuals cybersecurity breaches are a nuisance, and to most businesses they are, well… the cost of doing business. This can’t be compared to plane crashes or car accidents that often (almost always?) lead to real tragedies and lost lives.

Safety controls are designed to reduce the need for decision-making, but security controls can’t

A seatbelt is a seatbelt, and all people need to do to protect themselves is to wear it. A seatbelt doesn’t have any configurations, doesn’t depend on context, and it works (or fails) the same way every time. The same is largely true for other safety features like airbags, guardrails, or child safety locks. All of them are designed to be passive, predictable, and effective without needing ongoing mental effort from the user. Once safety features are installed, they tend to do their job the same way across millions of identical scenarios. This simplicity and predictability are exactly what made such a huge difference when it comes to physical safety, whether we’re talking about seatbelts, sprinklers, balcony railings, or whatnot. These things just work, and we don’t have to think about them much.

Cybersecurity, on the other hand, is all about context. Every control depends on the nuances of the customer environment, configuration, business processes, data flows, and so on. Not only that, but security controls actively interact with one another, oftentimes in ways people didn’t predict, and a single tiny gap can lead to cascading failures. Implementing a security tool the wrong way can (and does) itself lead to a breach, making it easier for attackers to get in (imagine if wearing a seatbelt increased the likelihood of a car crash). Because security controls are so contextual, whether they end up being helpful all comes down to humans needing to make decisions, find time, and implement 1,000 knobs well that are all interdependent. To be successful in security requires a lot more than following safety protocols. People have to think about tradeoffs, what makes sense in a specific context; they have to follow up, convince others, and maintain ongoing operational discipline, all of which are much harder to get right than wearing a seatbelt.

Safety can be solved through standardization, but cybersecurity can’t

One of the main reasons why safety measures have been so effective is that safety can be solved through standardization. Seatbelts work because the environment is standardized. Each of the 100,000 models of the same car is designed to work the same, roads are designed to work the same, and physics works the same way in Florida as it does in California, or China, for that matter. In a standardized environment, we can be pretty successful in implementing standardized safety measures. Once we know that something works, we can just mandate that this measure be enforced for all similar situations moving forward.

This is not true for cybersecurity. First of all, company environments are deeply heterogeneous; they are always in a state of change, and everything is heavily customized per organization, per application, per workflow, and so on. This is why standardization simply doesn’t work for cybersecurity. Worse yet, standardization itself can become the source of vulnerability. Nothing shows it better than the issues we’ve been seeing with network devices, such as VPNs, when thousands of companies that standardized on the same tool all get breached at the same time when the exploit is discovered in that tool. Getting breached because your firewall has a critical issue is like having 1,000 cars crash on the same day because of the seatbelt design. You can see how the seatbelt analogy just doesn’t work again.

Closing thoughts

I can keep going with the list of reasons why safety and security aren’t comparable. Others seem to be chiming in as well. In the same LinkedIn thread I referenced above, Ivano Bongiovanni made another great comment: “My favorite distinction between safety and security is the one that calls out human intent behind adverse events. Safety: no malicious intent; security: malicious intent. So you can have a safe system that is not secure and vice versa.” Another great point. There are plenty of examples that all lead to the same conclusion: it doesn’t make sense to draw parallels between safety and security, and it’s time to put the seatbelts analogy to rest.

This is both bad news and good news. It’s bad because we might not be able to easily repurpose the model that worked so well for safety to solve cybersecurity problems. But, it is also good because we can avoid the trap of trying to borrow paradigms from slow-moving industrial car manufacturing and airplane production to the iterative and fast-paced world of technology. I think it’s just about time to accept that the best we can do is to continue maturing our defenses so that we can consistently make it harder and harder for the adversaries to achieve their goals. There is no other magic answer.

Oh, and please do check out the episode of Inside the Network with Dug Song - it’s a great one!

I admit I started reading this expecting to disagree, as I work in medical devices where safety and cybersecurity are often linked. But as I read further, it started to make sense, and simultaneously raised my blood pressure. What you describe here is exactly why I’m so passionate about cybersecurity. The game will never end; it will only change in scope or complexity.

Ross, this is a masterclass in why analogies matter. The 'seatbelt' comparison is comforting because it implies we can 'solve' security with a one-time engineering fix and some regulation. But as you pointed out, gravity doesn't have an exploit kit.

I’ve spent the last few months researching how this distinction applies to the AI agent space, and your point about standardization becoming a source of vulnerability is particularly resonant. Much of the industry is currently stuck in the 'Safety' mindset—which is essentially the seatbelt approach. They are trying to 'align' models and add toxicity filters, assuming a stable environment where the 'mind' of the AI just needs to be 'trained' to be good.

The real shift happening now—the one that actually mirrors your 'Security' definition—is moving the defense away from 'hope and alignment' and toward hardened infrastructure.

IMO, Instead of trying to make the AI 'safe,' we have to move toward:

- Architectural Isolation: Containing the blast radius so the environment isn't 'uncontrolled.'

- Identity Delegation: Managing what an agent is allowed to do, regardless of its 'intent.'

- Egress Controls: Treating AI agents as untrusted software workloads rather than misbehaving 'minds.'

Agree with you, it’s time to put the seatbelt analogy to rest. We need to stop treating these systems like people to be educated and start treating them like the heterogeneous, adaptive risks they are.

Really appreciated the clarity you brought with this article!