Securing critical infrastructure in the US is not a policy problem, it’s a market problem

Discussing the problems surrounding operational technology (OT) and industrial control systems (ICS) security, factors that make the OT/ICS security markets hard to compete in, and their future

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Also, over 1,600 copies of my best selling book “Cyber for Builders: The Essential Guide to Building a Cybersecurity Startup” have been delivered by Amazon so far. This book is unique as it talks about building cybersecurity startups. It is intended for current and aspiring cybersecurity startup founders, security practitioners, marketing and sales teams, product managers, investors, software developers, industry analysts, and others who are building the future of cybersecurity or interested in learning how to do it.

This week, over a thousand people are going to attend S4x24 in Miami South Beach to discuss the future of OT and ICS security. Although I won’t be making it to the conference, I would like to contribute to the discussion. This article, which dives into the challenges and opportunities around building OT security startups, is my attempt to do so. Big shoutout to Paulo Dutra for encouraging me to write it.

The need to secure both IT and OT technology in critical infrastructure sectors

Fundamentals of critical infrastructure

As the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency explains, “There are 16 critical infrastructure sectors whose assets, systems, and networks, whether physical or virtual, are considered so vital to the United States that their incapacitation or destruction would have a debilitating effect on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination thereof”. The list of these sectors is as follows:

Chemical Sector

Commercial Facilities Sector

Communications Sector

Critical Manufacturing Sector

Dams Sector

Defense Industrial Base Sector

Emergency Services Sector

Energy Sector

Financial Services Sector

Food and Agriculture Sector

Government Facilities Sector

Healthcare and Public Health Sector

Information Technology Sector

Nuclear Reactors, Materials, and Waste Sector

Transportation Systems Sector

Water and Wastewater Systems

One way to see how critical these segments are is to overlay them with the US GDP data. Over 50% of the US GDP sectors such as finance, manufacturing, healthcare, construction, transportation and warehousing, utilities, mining, and agriculture, to name some, are deemed to be critical to the nation’s existence. It can be argued that critical infrastructure sectors are the very means by which the United States is able to ensure its existence as a nation and maintain its leadership as a global economic power.

Source: U.S. GDP by Industry in 2021

Fundamentals of operational technology (OT)

Whenever we hear the word “cybersecurity”, it is usually assumed that what is being discussed is the security of information technology (IT), or computers used for processing and management of information. While that is a fair assumption, and the vast majority of security teams are indeed focused on safeguarding the IT infrastructure, there is another important problem area that needs our attention.

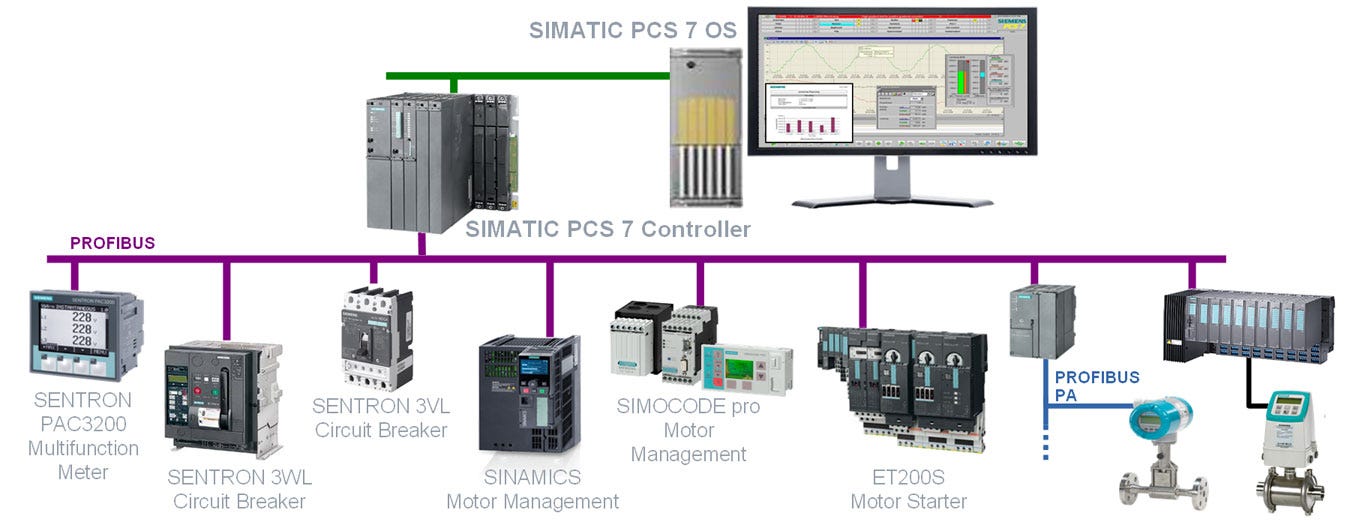

I am talking about OT, or operational technology, a term used to describe the hardware and machinery responsible for the management of industrial operations. Another abbreviation that is frequently used when we discuss OT is ICS or industrial control systems. Industrial control systems are a subset of OT used to describe a wide variety of systems, devices, networks, and controls used to operate industrial processes such as electrical plants, water plants, factories, and data centers. Here are some examples of industrial control systems.

Source: IvesEquipment

Critical infrastructure sectors heavily rely on operations technology (OT). From water pumps and sensors installed on nuclear reactors to automatic train supervision systems, UV detector machines, pacemakers, and medical lab equipment - all these technologies are critical to our lives and need to be secured.

In the past, IT networks and OT devices were not connected: each was managed by different teams, used to achieve different goals, and communicated via separate networks. Fast forward to today, and that has changed. OT devices are increasingly being connected to IT networks, software is being used to collect data from OT systems, monitor and improve their operations, and IT and OT teams are expected to work hand in hand to drive the necessary outcomes. The growing interconnectedness between IT and OT is referred to as IT/OT convergence, and it is one of the main reasons why securing critical infrastructure means securing both IT and OT technology in critical infrastructure sectors.

Critical infrastructure security and public awareness

Today, it is hard to find a person working in cybersecurity in the US who would not be talking about the importance of securing the nation’s critical infrastructure. However, this level of awareness is a fairly recent phenomenon.

After Stuxnet events became public in 2010, it was no longer a secret that supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems and various components of operational technology are incredibly vulnerable to cyber attacks. However, the threat felt too far away, and prior to 2015, most discussions about critical infrastructure security felt somewhat theoretical. On December 23, 2015, when the Ukrainian power grid was hacked by Russian state-sponsored actors, this changed, and the whole world learned the importance of securing the OT/ICS systems. Nearly 230,000 people in the western regions of Ukraine had to endure a power outage for up to six hours. Just a year later, on 17 December 2016, a cyber attack on the electrical substation just outside the Ukrainian capital Kyiv, cut one-fifth of the city's power consumption. The 2015-2016 attacks were then followed by the NotPetya ransomware attack of 2017, dubbed by the White House as the “most destructive and costly cyber-attack in history”. The total cost of the 2017 attack was estimated at nearly $10 billion globally.

While individual companies have been buying OT security solutions for many years, OT security as a market only started to emerge around 2018. This coincided with the rise of ransomware and attacks focused on causing damage and destruction which made asset owners and regulators tasked with keeping the critical infrastructure secure uneasy. Since the criminalized threat activity was no longer seen as something the government was expected to fix, plenty of founders and investors decided to seize the opportunity. It was around 2018 when the idea of intrusion detection came to OT security, and VCs got excited as it finally started to look like OT security could be similar to other SaaS with per-seat licenses, predictable growth, and the ability to scale. Venture capital fuelled the rise of OT security vendors, and allowed startups to pour money into marketing and start evangelizing the importance of securing operational technology.

While the scale and intensity of attacks by the state-affiliated actors on Ukrainian infrastructure are mind-blowing, it is understandable that an average American was not all that concerned with what was happening somewhere far away, on the other side of the ocean. The real wake-up call for the US was sounded on May 7, 2021, when Colonial Pipeline, an American oil pipeline that carries gasoline and jet fuel mainly to the Southeastern United States, suffered a security incident that forced it to halt all pipeline operations. The attack caused fuel shortages in the United States and forced US President Joe Biden to declare a state of emergency.

Another, most recent technical issue from just over a year ago showed what could happen when a critical system goes out of order. The 11 January 2023 was a challenging day for US aviation: more than 1,300 flights were canceled and nearly 10,000 more were delayed due to an FAA system outage. Although the outage was not, according to investigations, caused by a security compromise, the incident demonstrated how one system going down can halt transportation all over the country.

The attacks on the Ukrainian power grid demonstrated the scale of damage that can be inflicted when nation-states decide to attack another country’s critical infrastructure. On the other hand, the ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline showed that financially motivated actors can also cause severe damage to the economy and throw society into chaos and panic. Today, it is no longer a secret that the country is under constant threat. As recently as several weeks ago, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), National Security Agency (NSA), and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) assessed that Chinese state-sponsored cyber actors are “seeking to pre-position themselves on IT networks for disruptive or destructive cyberattacks against U.S. critical infrastructure in the event of a major crisis or conflict with the United States”. The public is now aware of these developments, and people are asking the government to do something about the risks.

Sobering reality of the OT security market

Securing critical infrastructure means securing both IT and OT technology in critical infrastructure sectors. For the past several decades, we have made good progress in the field of IT security. Although levels of security maturity at an average enterprise remain somewhere between low and moderate, and we are accustomed to reading about new security incidents daily, it is important to acknowledge the work that has been done and the milestones that have been met. For example,

Although having more startups does not automatically lead to better security, and the proliferation of tools causes people to beg for market consolidation, the fact remains that buyers have plenty of options to choose from when they are looking for security products. There are thousands of security vendors of all kinds willing and able to help solve different problems companies are struggling with.

Although having many security courses, certifications, conferences, events, and webinars doesn’t automatically mean that learning security is easy, the fact remains that security practitioners have plenty of options to choose from when they are looking for ways to uplevel their knowledge. There are hundreds of short courses and degree programs, online labs and in-person capture the flag (CTF) competitions, and more.

Although simply having more people joining the industry isn’t necessarily going to solve our problems, the fact remains that there are hundreds and thousands of aspiring security practitioners focused on developing their skills, improving their ability to design solid defensive measures, and growing their careers in the field.

Although simply funneling capital into security startups whether or not they solve important problems won’t necessarily make us more secure, the fact remains that we’ve got a lot of funding for research and development and building innovative security solutions.

In other words, although we may be still struggling to secure IT networks, we have to admit that we’ve got many people trying to move the industry forward.

The same cannot be said about OT security. In particular,

Very few companies have budgets allocated to OT security.

Very few security practitioners understand the nuances surrounding OT security.

Very few vendors focus on OT security.

Very few investors are willing to allocate capital to OT security.

Very few educational programs exist that provide students with an understanding of OT security.

While the US government continues to stress the importance of securing the nation's critical infrastructure, the reality on the ground is grim, and there is nothing that indicates that it is going to be changing anytime soon. The reason, in my view, is simple: securing OT and critical infrastructure is not a policy problem, it’s a market problem.

Securing OT and critical infrastructure is not a policy problem, it’s a market problem

Fragmented market

Operation technology is a highly fragmented market. There are a few reasons why that is the case:

Every critical infrastructure segment relies on operational technology unique to its needs. Sensors seen in public utilities will be vastly different from those in rail and transportation systems, and therefore defenses that need to be designed for them will also be unique.

Every critical infrastructure segment is subject to different regulatory and compliance requirements, frameworks, and certifications. Since all of them are heavily regulated but the regulations that apply to each are unique, it is very hard for a single company to be well-versed in different market segments at the same time. What makes the regulations even harder to deal with is the fact that some providers are regulated by the federal government while others by their state authorities. There's a large disparity between how they define prices, how they are able to talk about safety, reliability, and security, etc.

In different segments of critical infrastructure, regulators look at different metrics. In financial services, for instance, regulators care about factors like risk management controls and capital adequacy. Neither of these impede the companies’ ability to generate profits, and higher profits mean more money to protect, and more ability to invest in security. Companies in the utility space, on the other hand, are required to provide their services at what’s called a just and reasonable price. This puts a cap on their profits and subsequently limits what they can spend on security, making it inevitable that security will always be under-prioritized and under-invested.

Every critical infrastructure segment has different ways in which organizations obtain approvals for security budgets. In financial services, for instance, OT security is very similar to IT, both in terms of technologies that need to be protected, budget owners (in both cases, it would typically be a CISO), and the way products are bought. In manufacturing companies, even when they have a full-time CISO, OT security is frequently the responsibility of someone on the factory floor, and as such, there may not even be a separate security budget.

Lack of clear security budget and budget owner

Any startup operating in a green field market or working to establish a new category will inevitably run into a wide variety of challenges. The number one task of any company that wants to solve an impactful problem is to find a person who experiences that problem and has the budget to solve it. When enterprise-focused security startups design their go-to-market, they know that they need to target Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs), Director-level security leaders, and in some cases, Chief Information Officers (CIOs). The OT security startups, on the other hand, do not have such clarity.

When ICS OT companies go to market, they try talking to CISO to see if they own industrial cybersecurity risk only to realize that most of them are exclusively focused on IT security. For instance, in manufacturing, there are cases when a CISO is solely focused on IT, and OT security is supposed to be owned by a VP of Operations, or a Chief Operating Officer (COO) who might be well-versed in the nuances of the plant environment but know nothing about security. There are also cases when a CISO is expected to own the OT side, but the budget resides with the plant leadership owned by the VP of Operations, who may not understand security and who may assume that it’s already handled because they have a full-time CISO.

The problem is compounded by the fact that there is no clearly defined security budget across water treatment facilities, electrical utility providers, oil and gas firms, factory floors, and other market segments heavily reliant on OT. And as there is no budget, there is naturally no clear budget owner startups can talk to. Navigating the complexity of procurement at scale and trying to grow the company in these conditions is very hard.

Challenges finding early adopters and later crossing the chasm

Buyers of OT security are some of the most conservative technology buyers on the planet. The level of risk aversion is real because there are no do-overs when things go offline or a critical function breaks down. If electrons, water, or trains stop moving from point A to point B, it will have real-world ramifications, and thousands or even millions of people could have their lives affected in an instant. Some risks can have catastrophic impacts: if a pump responsible for supplying water to the nuclear reactor goes down, hundreds of thousands of people could lose their lives.

Because of how critical all the operational technology systems are, it is no surprise that finding early adopters for OT security startups is incredibly hard. The S4 conference is one of the places that bring together early adopters - people seeking knowledge, networking, and new ideas from the industries where innovation is seen first and foremost as a potential risk, and only then as an opportunity. The S4 conference, however exciting and innovative, is not a representation of where the industry is today. The vast majority of technology leaders from organizations that fall under the definition of critical infrastructure are not regular attendees of S4 or similar events. Moreover, since power plants, utilities, and oil and gas facilities, to name some, are usually located far from large metropolitan areas, they don’t get to benefit from the ecosystems and networks offered by urban centers.

While finding early adopters for OT startups is hard, crossing the chasm and reaching the early and late majority is exponentially harder. For instance, millions of power lines that run through the country are managed by people who live far away from large metropolitan centers and don’t go to leading industry conferences to hear about innovation. Any OT security startup looking to achieve impact will have to find a way to market to the long tail of prospects scattered all over the country.

Challenges of dealing with the legacy infrastructure

It is often said that OT is a new field, but when it comes to the level of maturity, it lags behind its IT counterpart by about two decades. Although the OT space is new, the challenges are old. Remote access, devices with default passwords, and other issues that IT has mostly solved in the 1990s and early 2000s, within the ICS space these are still problems that are being tackled today. This is because in OT, asset life cycles are measured in decades, not years, and many new technologies are entirely off-limits. For example, in industrial control systems, the adoption of cloud technologies has been and will continue to be quite limited. Some more innovative and technologically-inclined industries such as pharmaceuticals have started to use cloud in their lab environments. In more conservative fields such as electricity, mining, and oil and gas, the data may be sent to the cloud for computational analysis, but nothing is allowed to go in.

What makes dealing with legacy infrastructure in ICS especially hard is the fact that these systems were architected in such a way that redundancy is prioritized over efficiency. Having multiple redundant systems running in parallel greatly increases the complexity that founders and the products they are building are expected to handle.

In OT security, moving fast and breaking things is not acceptable. Building security solutions and getting them adopted by prospects afraid of anything new is hard and takes a long time. Customers are not going to install an agent on a water pump that has the potential to affect its work or accidentally interfere with a critical system. Instead, those building OT security solutions have to be deeply familiar with the broad range of controls, understand the protocols, and rely on passive detection. The ability to invest time and effort in learning how the infrastructure works is critical. If you go into any facility built in the 1980s and 1990s, you will find assets installed many decades ago. It’s highly unlikely that the startup will be able to find any documentation or people who know what their facility’s protocol coverage is. Founders will have to invest time and effort to reverse engineer technologies created 30-40 years ago, understand what normal looks like, and what detecting threats looks like as a result. It takes time, money, and effort to do this well.

Complexity designing a scalable go-to-market strategy

The previously discussed market fragmentation, the lack of clear security budget owners, the absence of early adopters, and the challenges of having to deal with legacy infrastructure make designing a scalable go-to-market strategy in the OT security space incredibly hard.

Often the first adopters are friends and family, but this doesn’t scale when the company is expected to develop a repeatable go-to-market motion and grow past the initial set of five to ten customers. Among all the challenges, the hardest one to overcome is the absence of a clear budget owner with the mandate of keeping the operational technology safe and secure.

Since places such as power plants and gas pipelines don’t have staging environments, startups cannot get away with offering buggy minimum viable products (MVPs). Instead, they have to invest in building robust, comprehensive solutions upfront, before they can get their first customer, or even do a single proof of concept (POC) trial. This, along with the highly fragmented and heavily regulated total addressable market (TAM) means that companies in the OT security space require a lot of capital to get going.

Long sales cycles and the need to capitalize expenses

In OT security, growth takes time, and it is rarely incremental. It’s common for a prospective customer to deploy a few sensors on a critical asset, or do a short-term service engagement, and then five years later initiate a few-million contract with the vendor. Sales cycles in the segment are long, especially for products: while it may take two to three months to get a service engagement vetted and approved, it could take two years or more to procure a product. Getting in on the buying cycles in OT is hard because decisions to build a new plant or a new reactor are made once a decade, and once everything is finalized, there are no changes that would make it possible for a startup to come in in the middle of the implementation stage.

The revenue of OT security companies is lumpy: big, multi-million dollar purchases are followed by periods of no revenue. The reason why this is the case has to do with the economic incentives on the buyer's side to capitalize as many of its expenses as possible. The way that these companies can account for earnings comes through being able to make their operations and maintenance expenses as low as possible, and their capital expenses as high as they can. This enables them to go back to regulators and say “It turns out that it's very expensive to secure the power delivery so we need to renegotiate our rates”. In practical terms, this means that solutions that can be treated as capital expenses are much more likely to get bought compared to solutions that can only be treated as operating expenses. Or, to put it simply, a 5-year contract with an upfront payment for an on-prem tool is more likely than the subscription contract for a SaaS solution billed monthly. In markets where the government limits profitability (electricity, utilities, etc.), there is a natural aversion to buying anything that can’t be capitalized. This approach does bring some upsides for startups. First, companies can get the money upfront, and invest it in research and development, growth, and product innovation. Second, while it takes a long time to sign a new deal, it also makes it much less likely that the customer will churn. Lastly, long-term contracts enable smart founders to plan their expansion years ahead.

Despite all the positive sides of the way OT products are bought, in my view, the negatives still outweigh the positives. One of the most critical downsides is the inability of OT security startups to attract venture funding. Any traditional investors experienced in supporting B2B SaaS, are looking for predictability of growth, recurring revenue, and an easy-to-understand pricing model (per seat, per amount of data ingested, etc.). The big upfront payments followed by months with no revenue make it very hard for investors to understand and forecast how the company is doing, and subsequently greatly increase the risks of investing in OT.

A small pool of potential founders

The pipeline of potential founders who could build a startup in OT security is incredibly small. One needs to have experience in the sector and have a good understanding of technology, architecture, change management, regulation, and policy, to name a few. The community of asset owners wants to see empathetic founders who know what’s at stake and understand that if that pump goes offline, the facility won’t be able to put water into the reactor and everyone will die. It’s hard to have this level of empathy and intuition when a person doesn’t come from that community.

While understanding IT is important, there is a lot that doesn’t translate well in the OT space. Coming to the operations leader of a large utility and showcasing a portfolio of product implementations from financial institutions won’t work. Neither will an attempt of a team of product managers and software engineers from Silicon Valley with no prior experience with ICS to quickly reverse engineer the needs, understand requirements, and build an MVP.

Successful founders in the OT space need to have a deep knowledge of operational technology. Ideally, they would have accumulated many different perspectives - as ICS SCADA engineers, sysadmins in corporate IT, leaders of large-scale projects within the IT department at a utility, security leaders in the OT space, and the like. In practical terms, finding an entrepreneur who has accumulated so many perspectives and experiences and has an in-depth understanding of the nuances within the industry while remaining passionate enough to build a company is very hard.

Working for asset owners is not a hard requirement for starting a successful OT security company. Another path is having experience in the military or a special agency where people can get exposed to what nation-state attacks look like. At Dragos, one of the leading OT security companies, 7 of the first 11 people came out of NSA. The founders of Claroty, another leading OT security company, bring experience from the Israel Defense Forces. The supply of people who understand operational technology environments is small; fewer come from asset owners than intelligence agencies and special forces.

The inability of companies to design incentives that attract the best talent into OT

Markets where profits are higher are known to invest more in their security compared to those where profits are capped or lower such as commodities, and utilities. Lower investment in security, legacy infrastructure, and unclear ownership do not usually make companies in critical infrastructure highly desirable workplaces for security practitioners.

The very best security engineers and SOC analysts are driven to places where they can get higher remuneration and better growth opportunities. We are witnessing a brain drain away from areas of OT security, and while politicians are continuing to state how important OT is for national security, people who are expected to defend critical infrastructure have all the reasons to seek better pay and working conditions.

VCs losing money on OT security

Another factor that makes OT security a tough market to compete in is the lack of investors willing to bet on the future of this area.

The VC's excitement about the OT security which started around 2018, didn’t last too long. In the early 2020s, many of their portfolio companies started to collapse. The OT security market has proven to be a complex one to crack, and many investors lost their money. The reasons why this happened are all the same - market fragmentation, the absence of clearly-defined buyers, the need for large amounts of capital, and all the other discussed above challenges.

Generalist VCs which constitute the majority of the market have no real reasons to consider OT security as an investment area. Their investment mandates are quite broad, so they aren’t in the business of finding the best security company - they are looking for the most promising startups regardless of the market. When they want to allocate money to companies in security, they have no reason to choose high-risk areas like OT, with hard-to-decipher TAM, low Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR), and all the challenges we just discussed. Instead, they choose higher-growth categories like cloud security or identity.

Cyber-focused VCs, on the other hand, have fewer companies to choose from and eventually end up investing in OT security. However, since a good number of investors lost money in OT, they are not too eager to allocate more capital to this segment. This behavior is both understandable and incredibly common as the same has happened in sectors such as cleantech.

The two types of investors that remain loyal to OT security today are corporate venture funds such as NextEra Energy Investments and Siemens, and VC firms where the adopters of these technologies act as limited partners (LPs) such as Energy Impact Partners. Outside of these two, there is a clear lack of investors willing to bet on the OT security market.

Other reasons why OT security remains unattractive for VCs include:

It’s unclear if the market segment can produce public companies with $100M annual recurring revenue and more. While many argue that the total addressable market in OT is large, so far there is little evidence that a company can successfully IPO in this segment. VCs aren’t afraid of slow-moving, complex markets; companies like Palantir and Anduril are clear examples of that. What they are, however, afraid of is small markets that are slow-moving and complex, and that don’t have established budgets.

It’s hard to build a product-only OT security company, and foregoing an opportunity to develop relationships and a track record by offering services is often a poor choice. VCs don’t love seeing product companies that have a large subset of their revenue come from services. Service companies are not attractive enough from the margins and revenue multiples standpoints, and it's hard to see examples of companies that started in services and were able to successfully pivot into products.

An average VC isn’t familiar with capital-intensive companies and doesn’t understand OT security buyers. Compounded by the fact that there have been no large exits, it’s hard for investors to think that something is going to change and these trends will magically reverse.

There’s a mismatch between the recurring revenue model VCs would like to see, and the way the OT security is bought. OT security buyers purchase tools as a one-time acquisition of equipment to make the economics work for their business. That makes it very hard for VCs to understand if the company is growing, or if this one-time purchase is an anomaly.

Solving the OT security market problem

Having taken a close look at the ICS and OT security space, I am convinced that there is a complete misunderstanding of what we need to secure the US critical infrastructure. Today, most discussions about ICS and OT security happen in the circles of policymakers, special agencies, and the military. This makes many people assume that critical infrastructure security, and subsequently, OT security, can be solved by issuing executive orders, drafting directives, and passing new legislation. While all this work is without any doubt important, we must recognize that in any market economy, complex ecosystem-level problems cannot be solved without market participation. In other words, securing OT and critical infrastructure is not a policy problem, it’s a market problem. To solve it, we need to look for ways to design systems that create the right economic incentives and address the systemic issues that OT, ICS, and critical infrastructure are known for.

Training the next generation of OT security practitioners

To start, we need to prepare the next generation of OT security practitioners. While there are a good number of educational programs, bootcamps, and training providers, the vast majority of them are focused on IT, not OT security. If securing critical infrastructure is indeed key to the nation's survival, we need to see more educational programs focused specifically on OT. It would also make sense for the government to subsidize training for OT security practitioners.

Another important part is making working in OT more attractive than it is today. Without redesigning the very way security budgets are allocated, it will be hard to change the compensation levels of the few OT security practitioners we do have and retain those who will end up joining the field.

Developing support systems for OT entrepreneurs

To get more security practitioners willing and able to take risks and start OT security companies, we need to do what it takes to build a pipeline of OT startup founders. A lot of this is going to happen organically, especially as people who accumulated experience in successful OT security product companies such as Dragos, Nozomi, and Claroty, will go on to launch their own startups. Dragos alumni, for instance, founded SynSaber and Insane Cyber.

Although the incubator and accelerator model hasn’t proven to be as effective for security companies as we had hoped, there could be a case for designing these kinds of programs focused on OT. Many people working for asset owners and in agencies such as the NSA, CIA, and FBI, have a great technical understanding of what it takes to secure critical infrastructure but lack experience in building products and taking them to the market. This is where OT-focused accelerators and incubators can step up to fill the gap and provide the resources founders need to succeed. The good news is that we have started to see some effort in this direction. In 2023, the Clean Energy Cybersecurity Accelerator (CECA), the initiative managed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and sponsored by the US Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response, Duke Energy, Xcel Energy, and Berkshire Hathaway Energy graduated its first cohort of companies. Its remains to be seen what results will be produced by CECA’s work but it's great that we are seeing some movement in this area.

Providing capital to OT security startups

We need to bring more capital into OT security. Over the past decade, many VCs got burned many times over investing in companies that go to market to service the risks of the critical infrastructure providers. Now, while the US is growing weak and helpless in the critical infrastructure security arena, investors are shying away from investing in OT security.

There are legitimate reasons why investors stay away from OT. After all, they are in the business of generating returns to their limited partners, and not in the business of solving national security problems (for that, there are other entities). We should continue putting efforts into changing the state of ICS and OT markets. The challenge is that ecosystem-level changes take time and we don’t have as much time; we need solutions today.

The good news is that we have a very successful model for what the government could do to address this problem. I am talking about In-Q-Tel (IQT), an American not-for-profit venture capital firm that invests in companies that provide the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and other intelligence agencies with the tools they need to achieve their objectives.

The In-Q-Tel model can be replicated in the field of OT security. I am not sure what it would look like, and what would the basis for it be. Could it be a collaboration between NSA, CISA, and private sector organizations? Maybe. A public-private partnership between government agencies and organizations from different critical infrastructure sectors? Maybe. Something like Energy Impact Partners where utilities, energy providers, and other kinds of critical infrastructure players act as limited partners? Perhaps. A combination of all these? Possibly. What matters more than the format is the fact that we need an investor who would be willing to put national interests over profitability. We need investors looking to build strong portfolios that keep adversaries off the US grid, and away from the American banks, medical devices, car charging infrastructure, and so on. And, since they don’t currently exist, I think they must be established. If the government continues to repeat that OT security is important, it must be willing to fund it or create incentives for someone to do it.

Fostering a cohort of early adopters

Lastly, we need to do what it takes to expand the cohort of early adopters in the OT space. Events such as S4 are great, but we cannot hope that they will solve the problem without additional support. One idea that has circulated for a while is the formation of public-private OT security buyer consortiums that attempt to consolidate the buy-side of the market. A buyer's consortium made up of large OT asset owners like the DoD and publicly-traded companies subject to regulatory oversight makes sense given that these buyers are often trying to secure the same OEM products and services that may, by their very nature, be considered "dual-use."

One way to foster a cohort of early adopters would be to design innovation sandboxes - public-private partnerships between the government, a select cohort of companies representing different sectors of critical infrastructure, and private sector startups that can build and test their solutions in a safe, low-risk environment. We have also started seeing early efforts in this direction led by the US Department of Energy (DOE). Several days ago, the DOE announced $45 million to 16 projects across six states to protect the nation’s energy sector from cyber attacks. According to the announcement, these “projects will help develop new cybersecurity tools and technologies designed to reduce cyber risks and strengthen the resilience of America’s energy systems, which include the power grid, electric utilities, pipelines, and renewable energy generation sources like wind or solar”. It is still early to talk about the results of this program, but I am optimistic, and I think that we need even more of them, in other sectors of critical infrastructure.

A new hope: evolving markets and the maturation of OT security

Although it may sound like everything is doom and gloom, the reality is quite different. The market has evolved, it is no longer where it used to be. There is now The Forrester Wave™: ICS Security Solutions and the actual market focus that did not exist just a few decades ago. The growing number of companies focused on critical infrastructure security shows that things are slowly moving forward.

Source: Energy Impact Partners

Aside from the evolution of the OT and ICS markets, what is also changing is the dynamics within the critical infrastructure industries themselves. Take energy as an example. The energy economy is shifting, and this shift is creating new risk and opportunity landscapes. The energy economy is slowly moving away from central planning and on-demand power being generated at centralized facilities, to decentralized systems where each individual resident can generate their own power by leveraging solar panels and other sources of renewables. This shift requires new infrastructure, such as power generation and metering systems. Moreover, with everything getting digitized, it is no longer just the centralized power grid that might get attacked, but also the residential delivery and individual buildings.

What will the world look like when every home and every commercial office space is producing and consuming its own power? It will certainly look a lot different than it does today. Every commercial office will have to think about what a power backup looks like in a post-diesel economy. Every homeowner will need to think about securing the electricity their solar panels produce. While today’s power stations and utility providers can resist the cloud (and probably for the best), the infrastructure of the future is going to be built using software. In that world, there will be more opportunities for founders to have a staging environment with lower levels of risk to design, test, and rapidly iterate on innovative OT solutions. Breaking one residential power delivery system is not going to have the same impact as leaving the whole city without power. Changes like this may make it possible for startups to overcome friction from selling to large, centralized monopolies.

That, however, is going to be in the future. Today, we are dealing with problems that are much harder to solve, in an environment where few people understand the potential consequences of leaving them unsolved. For example, we are investing $7.5 billion to build a charging network for electric vehicles across the US, but it's unclear how it’s going to be secured, and what happens when vehicles imported from countries not friendly to the United States will be plugged into this network for charging.

Closing thoughts

Today, everyone is talking about critical infrastructure, industrial control systems, and operational technology security. Although public awareness of these problems is without any doubt important, it’s equally important to acknowledge that no solution will be able to work at scale without pirate sector involvement. The OT space is struggling with market fundamentals, and there are structural reasons why it’s hard to allocate money to security, build startups, and generate investment returns in this segment. We need policies that don't simply proclaim the importance of securing the critical infrastructure, but help address the challenges we discussed, attracting capital for startups, providing support for founders, and preparing the next generation of OT security professionals.

Gratitude

I am incredibly grateful to Paulo Dutra, Venture Investor at NextEra Energy, Dan Gunter, Founder and CEO of Insane Cyber, Tansel Ismail, Vice President at Energy Impact Partners, Jason Christopher, Vice President of Cybersecurity and Digital Transformation at Energy Impact Partners, Lior Frenkel, Co-Founder and CEO Waterfall Security Solutions, and Andrew McClure, Managing Director at Forgepoint Capital, for generously sharing their understanding of the OT, ICS, and critical infrastructure security space. Needless to say, all opinions and conclusions are my own.