Redefining “critical infrastructure” for the modern age

Why it’s not just power grid and water, but also tools like Stripe and Twilio that should be defined as critical infrastructure

If there is one thing regular readers of my blog have probably realized, it is that I rarely talk about the “hot” events. It is not that I don’t care what’s happening in the world (quite the opposite), or that I don’t think the news matters (they do). Instead, I prefer to discuss topics that are evergreen, meaning they remain relevant beyond the news cycle. A part of that is just me not having the time to keep up with everything and be up to speed on everything that would make me feel that I have an informed perspective. Another reason is that it’s pretty hard to offer something of value when your voice has to fight a lot of noise to be heard. However, equally importantly, I want Venture in Security to be relevant weeks and months following the newest, the hottest story, and a way to do it is to talk about problems that endure the booms and busts of social media excitement.

I am saying all this as a preface to the fact that this article is going to be different. Today, I am diving headfirst into the topic of the day, namely the AWS outage. Yet, even here, I’ll be doing it mostly my way.

This issue is brought to you by… Dropzone AI.

Most AI SOC Tools Are Still Unproven. This Study Actually Measured Them.

Your board wants proof that AI delivers on security operations, not vendor promises. The Cloud Security Alliance independently tested 148 real SOC analysts investigating actual alerts with and without AI assistance. No sales pitch, no cherry-picked results.

The findings? AI-assisted teams completed investigations 45-61% faster with 22-29% higher accuracy. Even skeptical analysts became advocates after hands-on use. More importantly, CSA maintained complete control over methodology and results, making this the independent validation your stakeholders actually trust.

If you’re evaluating AI for your SOC or need data that survives board scrutiny, get the full CSA benchmark study here.

The news about the AWS outage is not really about the AWS outage

Now I need to clarify something here: I am not actually going to be talking about the AWS outage. There are so many people talking about the ins and outs and reasons and outcomes and whatnot that having one more voice would not add any value. Instead of talking about AWS, I think it’s worth talking about the problem at hand in the broadest possible way.

It doesn’t take long to draw parallels between the AWS outage and the CrowdStrike outage some year and a half ago, and that is a fair comparison. I am sure there will be zealots saying “they are different events because…” (and many will be right), but as far as the outcomes go, these two events look pretty similar to me. In both cases, an important platform went down, which has led to the platforms that depend on it going down.

This brings me to the main point of today’s piece. In our discussions about supply chain risk, we have forgotten that there is something else at play here, which is that our digital world is powered by many components that are critical and virtually irreplaceable. I believe this is exactly the definition of critical infrastructure.

Redefining “critical infrastructure” for the modern age

The outdated definition of critical infrastructure

In most countries, the term “critical infrastructure” is defined by the government policy frameworks that go back many years and often even decades. CISA, a part of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, explains that “There are 16 critical infrastructure sectors whose assets, systems, and networks, whether physical or virtual, are considered so vital to the United States that their incapacitation or destruction would have a debilitating effect on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination thereof.” If you look at the list of these sectors, it will make a lot of sense: energy, water, transportation, communications, healthcare, financial services, manufacturing, and other areas are indeed all critical.

The US isn’t the only country that has compiled this kind of list. There’s the EU’s NIS2 Directive, Canada’s National Strategy for Critical Infrastructure, and I am sure if you ask ChatGPT, you’ll get examples of something similar for most countries (hopefully, all real).

All these frameworks originated at a time when national stability was closely connected to the physical world: electricity generation, oil pipelines, airports, and emergency response systems. The idea was that we need to protect infrastructure and systems that, if disrupted, can harm a lot of people or interrupt critical public services. This approach gave governments a consistent way to prioritize what matters most and allocate resources where they can make the most difference. Agencies can assign responsibilities to sector-specific regulators, figure out resilience requirements, and set up things like public-private partnerships to protect critical functions. These frameworks have proven very valuable to protect traditional infrastructure and coordinate emergency response during events like earthquakes. But, over time they also proved to be insufficient.

As time went by, people realized that the digital world matters, and we now see IT systems that support many critical functions also on the list. On paper, everything seems to suggest that we’ve learned that the digital world does matter. Certainly, the fact that AWS, Microsoft, Accenture, Oracle, and many other organizations are now a part of CISA’s Information Technology Sector Coordination Council is great news. What worries me is something else.

What modern critical infrastructure actually is

Transparently, I don’t know what this Information Technology Sector Coordination Council does (maybe I would if I had enough patience to read through its charter). To me, that’s not even the most important part. It all starts with who is on that council.

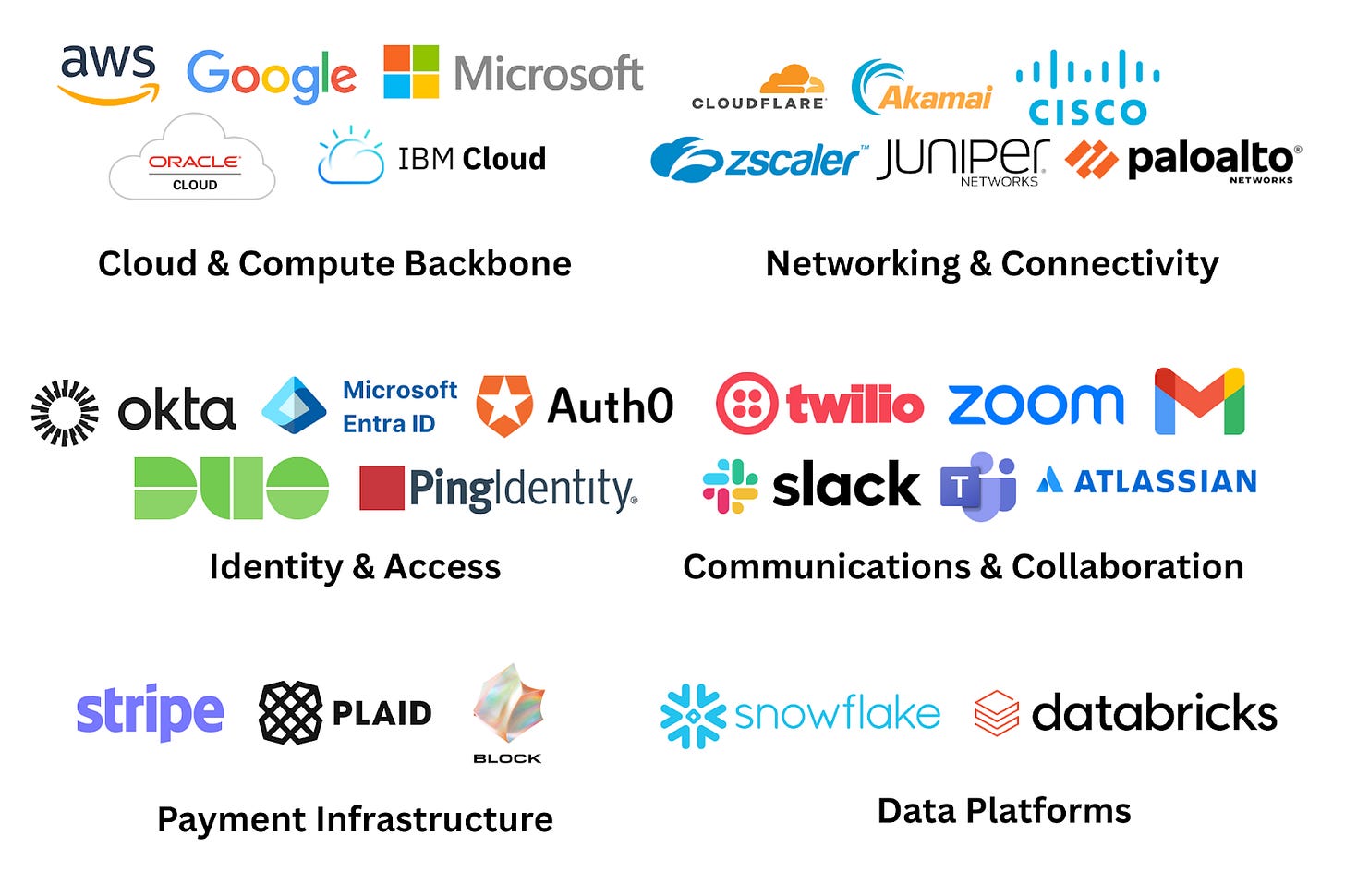

If you look closer, you’ll see that a large percentage of the organizations on that list are tech giants like Oracle, HP, IBM, Dell, AWS, and Microsoft, and cyber companies. This makes sense because these companies support the computing, storage, and network environments that government agencies, healthcare providers, and enterprises rely on every day. They provide the foundational technologies that power data centers and enterprise software, the modern equivalents of the roads and power lines that keep the digital economy functioning.

What’s less obvious is that the new generation of companies that I’d argue should be considered “critical” is not on the list. Take Twilio, for instance: it provides messaging and communications infrastructure embedded in everything from hospital appointment systems to two-factor authentication flows used by banks and government portals. If Twilio goes down, the entire authentication and notification systems can fail across thousands of organizations simultaneously. Similarly, Stripe processes payments for millions of businesses around the world, making it a critical layer of the global financial system. When Stripe’s services go down, the impact cascades across every single business that processes transactions online, like e-commerce, subscription platforms, and a large number of enterprises.

Then there are companies like Snowflake and Databricks, which have become central to how modern organizations store, process, and analyze data. These platforms host sensitive data for enterprises across healthcare, finance, manufacturing, and the public sector. Their availability directly influences an organization’s ability to operate, make decisions, and respond to incidents. Add to this list platforms such as Atlassian (which powers engineering collaboration), Okta (identity and access), Cloudflare (web and network security), and GitHub (software development infrastructure). An even better example is GoDaddy, a platform that manages a huge chunk of the world’s domain addresses. Each of these tools supports core business operations at scale, across companies of all sizes, and if any were to experience a prolonged disruption, the number of companies and whole sectors that would be impacted would be incredibly high.

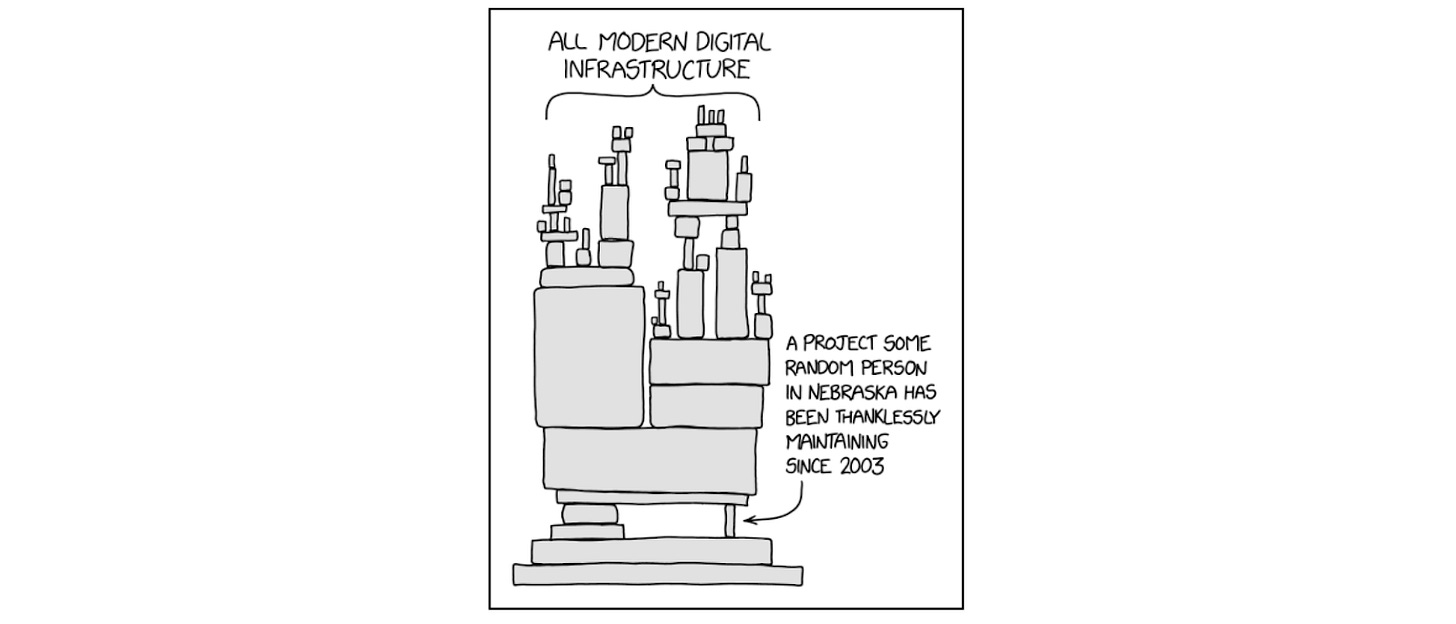

All this is to say that the present-day definition of “critical infrastructure” is completely outdated. Nearly everything in the digital world is interdependent, and a failure of one part of the system can lead to a cascading effect in ways we cannot even predict. If you want proof, think back to the CrowdStrike outage. In theory, an outage of the endpoint security platform should not have caused airports to crumble, but guess what, it did. I surely hope that we won’t see a growing number of outages, but we all know that our digital world is starting to look more and more like this famous meme from ages ago.

Looking into the future: this isn’t about words

When we think about the problem of protecting critical infrastructure, it’s definitely important to prioritize things that can impact the safety and well-being of people. Water, electricity, financial systems, and other areas are certainly the right things to think about first. And yet it’s important not to forget that the digital world relies on its own digital infrastructure that is all interconnected and, as we’re learning every year, incredibly fragile.

I don’t know what the future of this problem will look like, but I do know that this isn’t about playing with words. Recognizing what truly constitutes critical infrastructure has real, tangible consequences. How we define “critical” determines what gets regulated, what resilience standards are enforced, and what kinds of incident response and redundancy planning will be put in place. If we continue to treat cloud platforms, SaaS ecosystems, and digital intermediaries as ordinary vendors rather than as essential systems, we risk underestimating the scale of disruption a single outage can cause. A modern economy that runs on APIs, cloud workloads, and distributed services depends on a different kind of backbone, one that is global, digital, and deeply interconnected. We live in a world where an outage of Microsoft Entra ID can disrupt planes, an outage of Duo can disrupt hospitals, and an outage of Webex and Microsoft Teams can disrupt emergency response. We have to be able to at least acknowledge this reality and admit that many of the startups are now as critical to our functioning as a society as large tech giants. That, in my opinion, is the first step toward building resilience for the world we actually live in, not the one we used to.

Wow, it's interesting how you decided to jump into the AWS outage directly; could you perhaps elaborate on how this specific incident informs your broder vision of redefining critical infrastructure in the context of emerging AI-driven security solutions?