Not getting incentives right can kill a security initiative or a security startup

And it can make the lives of security teams really hard

I have been thinking about this topic for a while, and I am glad I have finally found the time to gather my thoughts into an article. I feel like it’s pretty rare to see people discuss incentives in cybersecurity (except for my friend Chris Hughes, who emphasizes this topic frequently in his blog and on LinkedIn). This is quite surprising given that everything in our industry centers around incentives. In this piece, I share some thoughts about this problem, discuss what I think are its most important aspects, and why more people should care.

This issue is brought to you by… Intruder.

As AI Enables Bad Actors, How Are 3,000+ Teams Responding?

Shadow IT, supply chains, and cloud sprawl are expanding attack surfaces - and AI is helping attackers exploit weaknesses faster. Built on insights from 3,000+ organizations, Intruder’s 2025 Exposure Management Index reveals how defenders are adapting.

High-severity vulns are up nearly 20% since 2024.

Small teams fix faster than larger ones - but the gap’s closing.

Software companies lead, fixing criticals in just 13 days.

Get the full analysis and see where defenders stand in 2025.

Incentives define how different departments prioritize security

If you read Verizon DBIR, CrowdStrike report, or any of the other credible, regularly produced reports about the root causes of breaches, or even if you simply follow the news, you’ll notice a consistent pattern:

Most breaches aren’t caused by some novel technology like AI or blockchain, nor are they the result of mysterious, never seen before zero-days.

The vast majority of security problems are not really security problems; they are problems that originate in other types of organizations and introduce security risks.

To put it differently, the vast majority of all the breaches happen because of some basic and boring problems. Someone forgot to change the password. Someone wasn’t able to track all the assets in a centralized system. Someone decided to grant a contractor more permissions than they needed, but forgot to revoke access when the contractor left. This list can go on and on, but the fact that matters here is that most of the time, what gets companies breached is something the security team can’t fix on their own. It is what my friend Yaron Levi calls “lack of operational discipline”.

None of this is rocket science, and anyone who has worked in security for over a year gets this. And yet, it still amazes me how often security professionals insist that things should be different, i.e., that engineers should care more about secure coding, that IT should prioritize access hygiene, that teams should think about security by default. The question that usually gets lost is Why should they? Why should any of this be true if nobody in the organization is appropriately incentivized to think about security? There’s the adage saying that “What gets measured, gets done”. To put it more bluntly, people will do what they’re incentivized to do.

A simple way to understand incentives is by looking at 2 things: what gets people promoted, and what gets them fired. At the highest level, the answer to both these questions is tied to organizational goals and key performance indicators (KPIs). Software engineers and product teams are incentivized to ship fast. Anything that hurts their ability to achieve this objective (extra design reviews, extended testing, and yes, lengthy security reviews) - all of that becomes an obstacle to be avoided. IT teams live in ticketing systems and are incentivized to close as many tickets as possible as quickly as possible without making people annoyed. Every IT support request (grant access to X, enable Y, open a connection to Z) means that there is a person in an organization who is looking for something, and they want it to happen yesterday. Everything is urgent, everything is on fire, everything has been requested by the manager, and everything needs to happen without any delays. Unsurprisingly, IT is incentivized to close the ticket as soon as possible and to immediately move to another (also urgent) request.

Every department has its own KPIs, and guess what, there’s only one team that gets measured on risk reduction, so it’s no wonder that, within most organizations, the only executive truly incentivized to care about security is the CISO. Until secure behavior becomes a part of everyone’s performance reviews, alongside execution, teamwork, and communication skills, this is not going to change.

Incentives define how different companies and industries prioritize security

The problem of incentives is even more apparent once we look outside of individual security teams and at the industry at large.

Every now and then, the whole industry gets excited about some new grand idea. Several years ago, it was about SBOMs, and as recently as a few months ago, it was about signing the Secure by Design Pledge by CISA (there are now 328 companies that have signed it). Obviously, I think Secure by Design Pledge is a good initiative; after all, it raises awareness that it’s important to think about security ahead of time, or as they say, designing security instead of bolting on security later. At the same time, thinking that an initiative like this is going to lead to any real consequences means not understanding how incentives work. To be clear, this has nothing to do with CISA or any of its programming; the problem is, once again, incentives.

I’ve talked about this before. When a company is just starting, it’s generally a few people in a garage, so all focus is on figuring out what to build and what direction to pursue. Obviously, thinking about security at this stage would be ridiculous: when the chances are 90-99% or higher that the whole venture will fail within a few months, the biggest risk isn’t a security breach, it’s not finding the right entry point. Let’s say the founders got this right and they were able to survive. From this point onward, the pressure only increases. The next challenge is getting to product-market fit (most startups never get there, so prioritizing it is paramount to company success). When the company has a product and zero customers, the number one priority isn’t to make the product secure; it is to get that first customer. Then the second, then the third, and on and on until the few lucky startups that get to survive and get to the growth stage are fully focused on growth. At no point in the company journey is security the number one priority.

Secure by design sounds great because, in theory, every company should indeed be making sure that its products are secure by design. In practice, security often slows business down, and in a world that prioritizes speed and execution over anything else, putting security first is never going to be easy. This is how, once again, incentives kill security, not just on the company level but also on the industry level.

Not getting incentives right can kill a security startup

For security leaders and practitioners, understanding how incentives work in our industry can help increase the success of security initiatives. After all, when security initiatives fail, it’s rarely because the tech isn’t there or because CISOs haven’t tried hard enough. Most security initiatives that fail fail because of misaligned incentives. A good example is the “shift left” movement, which failed because developers were never incentivized to own security. No security champions program can make developers prioritize security over velocity when they get promoted for the latter, not the former.

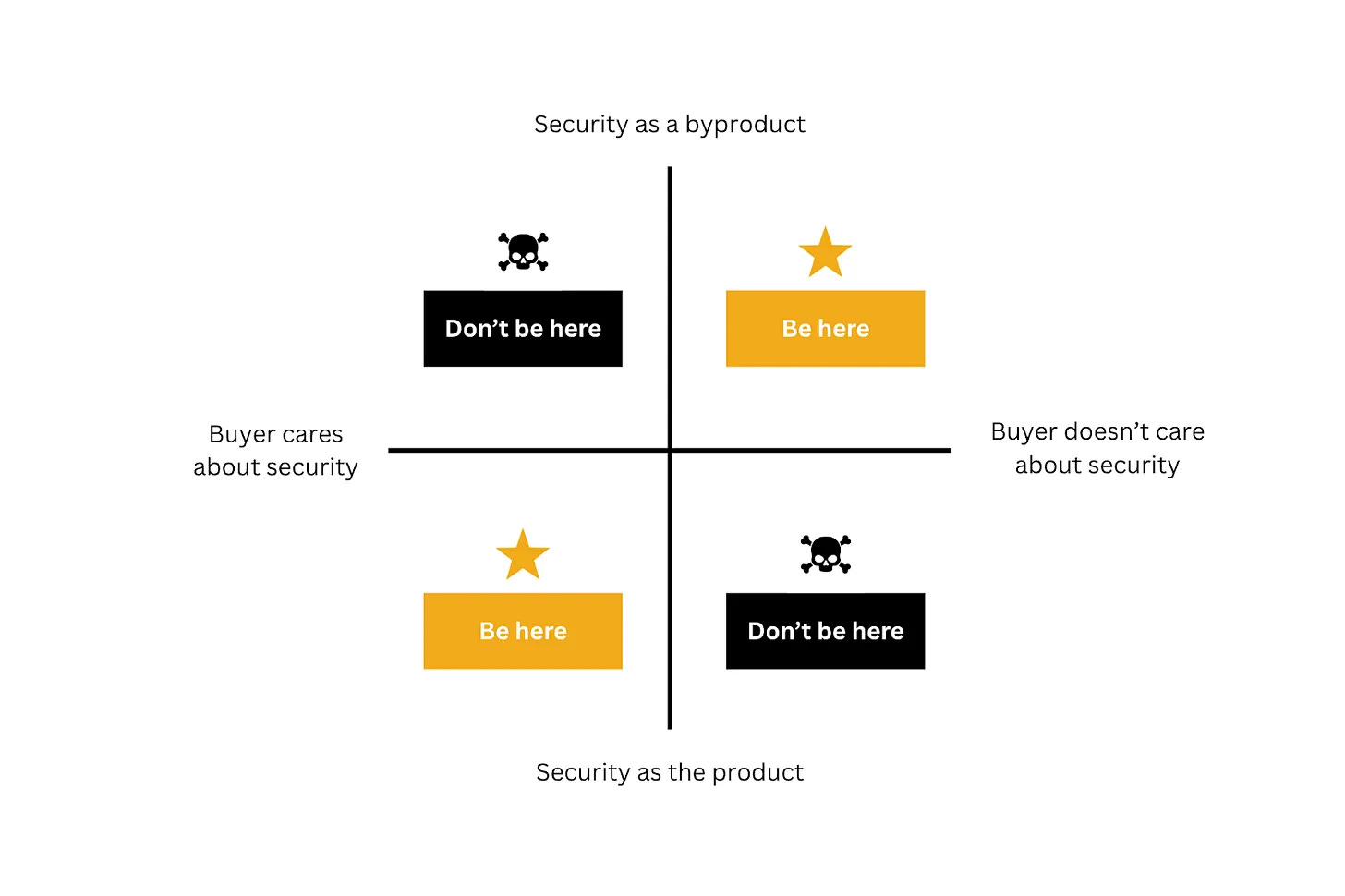

For cybersecurity startup founders, misunderstanding incentives can be the difference between building a successful company and a company that fails to get adoption. Many startups fail because they assume that different departments inside the company will care more about security than they actually do. This is especially the case for large enterprises that most security startups go after to begin with. The larger the company, the less likely it is that IT, infrastructure, or engineering will ever pay for, or be excited to implement a product, the primary value proposition of which is security. I have previously explained that to solve security problems, you don’t have to build a security company, and that the only way IT and engineering teams will buy a security product is if that product offers security as a byproduct of a different value prop they do actually care about.

Image source: Venture in Security

It’s not enough to understand organizational incentives and how different teams fit into the picture. I’ve also met founders trying to pursue large, ecosystem-level initiatives that also run into challenges with incentives. Every once in a while, someone with a great vision puts forward an idea of sharing threat intel or collaborating on detection data, only to learn that there are misaligned legal incentives (companies don’t want to expose breaches, spend time sharing data, or are afraid of accidentally sharing something that can be traced back to them). Many visionary ideas were killed by the realities of how legal liability, insurance, and other concerns make companies behave. What sounds like an obvious idea at a BSides talk oftentimes is simply not possible because of how the incentives work.

Looking into the future

Those who know me on a personal level can tell you that I am an optimist (and it’s not just because I wrote a manifesto of a security optimist). And yet, even I am struggling to see how, without radically shifting incentives, we can change the way security works. A lot needs to be done there, both on the organizational and industry levels. Some things generally evolve on their own, but incentives rarely do until something major happens.

I don’t think I have a good perspective on what can be done to change the way companies and society as a whole treat security. All I can hope is that the work we do as startups will make a small dent and help companies that care to improve their security.