Nobody ever gets credit for fixing security problems that never happened

We in security aren’t unique in our challenges, but we sure know how to take the problems everyone else has and crank them up to eleven.

Over 20 years ago, Nelson Repenning and John Sterman published an article in the Engineering Management Review, IEEE titled “Nobody ever gets credit for fixing problems that never happened: creating and sustaining process improvement”. When you read this article, you’ll realize that security is not unique in facing the problems it does, but also that our industry amplifies a lot of the challenges common in other fields and makes them much harder to tackle.

In this piece, I am doing a deep dive into the aspects of that great article that are most relevant to security. First and foremost, there’s the fact that nobody ever gets credit for fixing security problems that never happened. This has serious consequences for security teams and startup founders alike, as it effectively defines what initiatives (or products) are likely to be doomed from the start. It also answers many other questions, like why we blame people and not processes, why people are conditioned to work harder instead of working smarter, and why we love shortcuts even if the long-term impact of taking them can be pretty bad.

This issue is brought to you by… Intruder.

30M Domains Later, Here’s What We Found Hiding In Shadow IT

How much Shadow IT can you uncover with only public data? We ran the experiment and the answer was: too much. From backups holding live credentials to admin panels with no authentication, these exposures stay invisible to you but wide open to attackers. Read the research to see what we found and how Intruder helps you find it first.

Working harder vs. working smarter

Nelson and John, authors of the IEEE article, explain in very simple terms why security teams, similar to other functions, get stuck in the endless cycle of firefighting.

The idea here is simple. Security teams spend all their time dealing with incidents, tickets, and alerts - all the stuff that causes the well-known fatigue. Everything is on fire, the amount of work is overwhelming, and it’s impossible to ever reach a point where the team has time to pursue more strategic initiatives. Because the teams are bogged down doing all this manual, repetitive, low-value work, they never get the time to prioritize investing in foundational hygiene, architecture changes, or resilience. This creates a vicious cycle: the more they firefight, the more fragile the system becomes, and the more fragile the system, the more they need to firefight to keep it from falling apart.

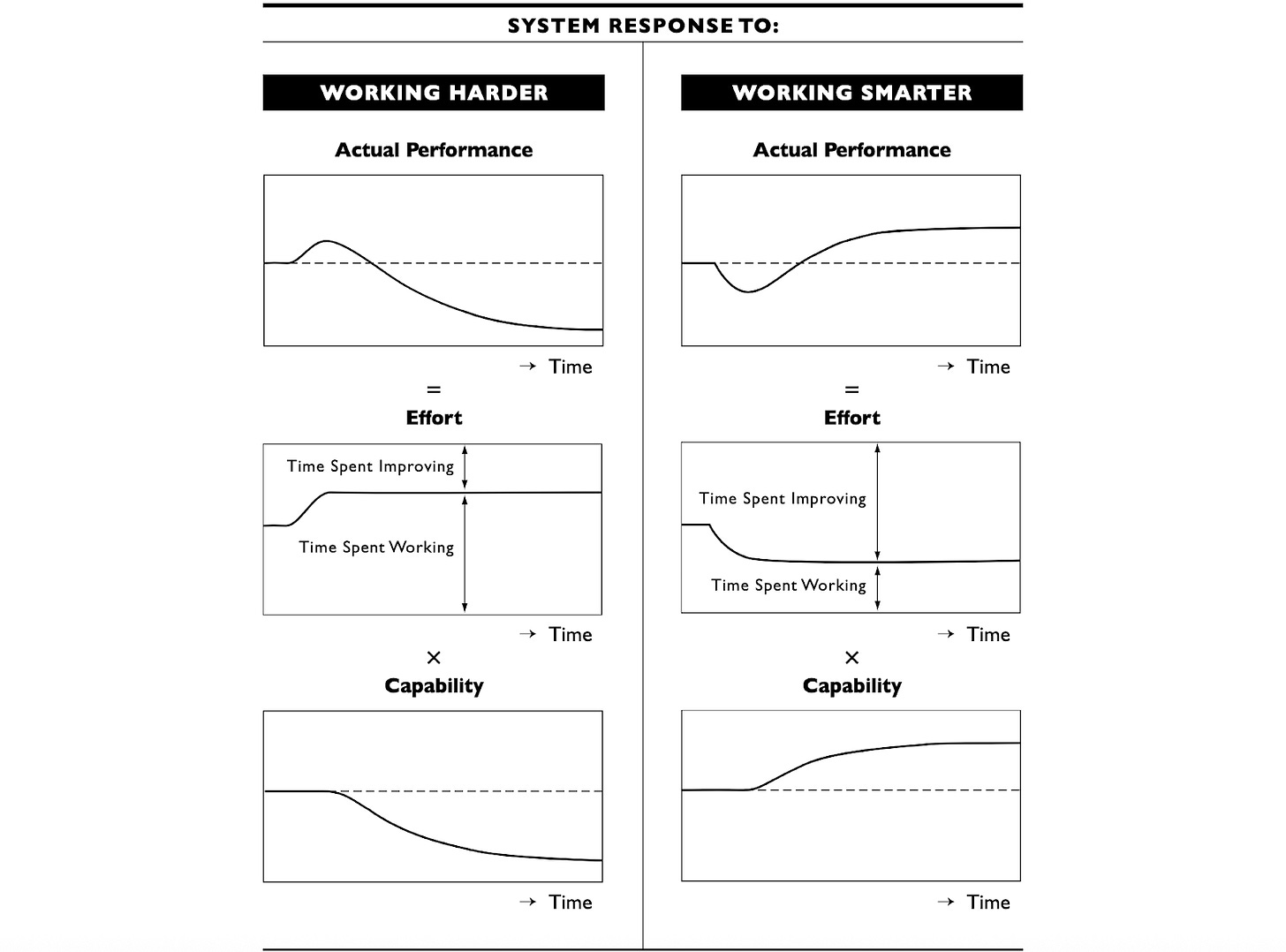

Nelson and John explain that the core reason for this is that working harder leads to immediate performance improvements. The more time and effort people dedicate to work, the better the results. Moreover, the improvement is immediate, and it’s easy to measure. The problem is that the benefits of working harder are pretty short-lived. As less time is spent improving processes, the capabilities slowly worsen, and eventually hit the point when simply working more won’t achieve much. This is why the authors describe working harder as “better before worse”: at first, working harder leads to immediate improvements, but over time, things get worse.

The so-called working smarter approach is the opposite. When the company decides to prioritize some larger-scale improvement initiatives, in the short term, things slow down because people are distracted by all the improvements and can’t work as hard on their day-to-day operational tasks. Eventually, however, the capabilities & the level of maturity increase more than enough to compensate for the initial productivity losses, and security teams become much more effective long-term. The article authors describe this as a “worse-before-better” dynamic.

We see how these things play out in the real world all the time. Foundational work like inventorying all assets, refactoring IAM, redesigning network segments, documenting architectures, and implementing zero trust initially slows everything down, and it can be hard to see how it can immediately reduce incidents. Over time, however, it is these operational improvements that give security teams superpowers and make them more effective, efficient, and productive in the long run. Since most people aren’t comfortable with the initial productivity dip that comes with working smarter, they prefer to focus on initiatives that lead to an immediate visible bump in productivity, even if, long-term, they’re actually less effective.

Image Source: California Management Review

Good security is destroyed by shortcuts

It can be said that good security is destroyed by shortcuts, not just those of people across the organization, but also shortcuts that security teams themselves are taking.

When security teams are pressured to do more with less time, they have to cut corners, and what naturally suffers are things that feel less urgent, like improvement initiatives, documentation, maintenance, and root-cause analysis. On one hand, this is understandable because in the short-term, taking this path can enable security teams to accomplish more in other areas and go heads-down on some operational day-to-day tasks. In the long term, they end up paying for these luxuries. Skipping threat modeling, not patching fully, ignoring IaC misconfigurations, not cleaning up IAM exceptions, and postponing other foundational work creates invisible long-term risk that adds up and eventually blows up in somebody’s face.

Here’s how authors of the article explain this phenomenon: “Shortcuts are tempting because there is often a substantial delay between cutting corners and the consequent decline in capability. For example, supervisors who defer preventive maintenance often experience a “grace period” in which they reap the benefits of increased output (by avoiding scheduled downtime) and save on maintenance costs. Only later, as equipment ages and wears do they begin to experience lower yields and lower uptimes.[...] Similarly, a software engineer who forgoes documentation in favor of completing a project on time incurs few immediate costs; only later, when she returns to fix bugs discovered in testing does she feel the full impact of a decision made weeks or months earlier.”

Power of the attribution error

Our industry is a prime example of what psychologists call the “fundamental attribution error”. Here is how the authors of the article explain this phenomenon.

“Suppose you are a manager faced with inadequate performance. Your operation is not meeting its objectives and you have to do something about it. [...] You have two basic choices: get people to work harder or get them to work smarter. To decide, you have to make a judgment about the cause of the low performance. If you believe the system is underperforming due to low capability, then you should focus on working smarter. If, on the other hand, you think that your workers or engineers are a little lazy, undisciplined, or just shirking, you need to get them to work harder.

How do you decide? Research suggests that people generally assume that cause and effect are closely related in time and space: To explain a puzzling event, we look for another recent, nearby event that might have triggered it. People also tend to assume each event has a single cause, underestimate time delays, and fail to account for feedback processes. How do these causal attributions play out in a work setting? Consider a manager observing a machine operator who is producing an unusually high number of defects. The manager is likely to assume that the worker is at fault: The worker is close in space and time to the production of defects, and other operators have lower defect rates. The true cause, however, may be distant in space and time from the defects it creates. Perhaps the defect is actually the result of an inadequate maintenance procedure or the poor quality of the training program. In this case, the delay between the true cause and the defective output is long, variable, and often unobservable. As a result, managers are likely to conclude that the cause of low throughput is inadequate worker effort or insufficient discipline, rather than features of the process.”

We see this in security all the time. Security teams say that breaches happen due to user errors because users “are dumb, not security-conscious, ignore policies, and can’t stop clicking on links,” instead of the system (overload, bad processes, etc.). On their part, company executives blame breaches on “bad security teams” instead of on systemic issues like chronic underinvestment, technical debt, complexity, and lack of automation.

The cycle of firefighting creates a hero culture

The fact that security teams are stuck in firefighting mode, and only relatively few are able to buy themselves time and space to prioritize strategic initiatives focused on working smarter, not harder, leads to serious consequences. Here’s what Nelson Repenning and John Sterman saw in their experience:

“As organizations grow more dependent on firefighting and working harder to solve problems caused by low process capability, they reward and promote those who, through heroic efforts, manage to save troubled projects or keep the line running. Consequently, most organizations reward last-minute problem solving over the learning, training, and improvement activities that prevent such crises in the first place. As an engineer at an auto company told us, “Nobody ever gets credit for fixing problems that never happened.” Over time, senior management will increasingly consist of these war heroes, who are likely to groom and favor other can-do people like themselves. As described by a project leader we interviewed, “Our [company] culture rewards the heroes. Frankly, that’s how I got where I’ve gotten. I’ve delivered programs under duress and difficult situations and the reward that comes with that is that you are recognized as someone that can deliver. Those are the opportunities for advancement.”

Reading this makes it clear that while security is certainly not the only place where people struggle to buy themselves time and space to work smarter, not just harder, it is surely a good example of this phenomenon.

Generally speaking, it is pretty rare to see security teams that are given enough power in their organization to implement preventative controls and prevent problems from happening. Prevention means friction, so it’s not only that “Nobody ever gets credit for fixing problems that never happened”, but it’s also that nobody can afford to introduce more friction.

Stuck in circumstances when they don’t have enough control, enough resources, and enough support, it’s no wonder that security professionals often fall victim to the so-called hero culture. It’s honestly hard to blame them: after all, most security people are trying to do their very best with the little support and resources they’ve got. If you are interested in learning more about hero culture and how it manifests itself in security, I recommend reading a piece Kymberlee Price and I published nearly 2 years ago, titled Hero culture in cybersecurity: origins, impact, and why we need to break the toxic cycle. (Spoiler alert - it’s as relevant today as it was two years ago).

Putting all this together

One of Venture in Security’s readers, Michael A. Davis, once left a comment under one of my other articles where he explained the consequences of the topics I am discussing here better than I ever could. He said: “What if this isn’t unique to cyber but is how ALL organizations handle prevent vs. react? I think the same dynamics appear in manufacturing (specifically quality control), healthcare (preventive medicine), and construction/infrastructure (the maintenance vs. repair cycle).

The pattern seems to be:

1. Organizations get trapped in firefighting mode because that’s what’s visible and rewarded.

2. First movers try to sell the organization that they should “work on tomorrow’s problems” to teams drowning in today’s crises and issues.

3. Only external forces like breaches or regulatory mandates create enough pain to break the cycle.

4. Second movers arrive just as the market tips from “theoretical risk” to “urgent need”.

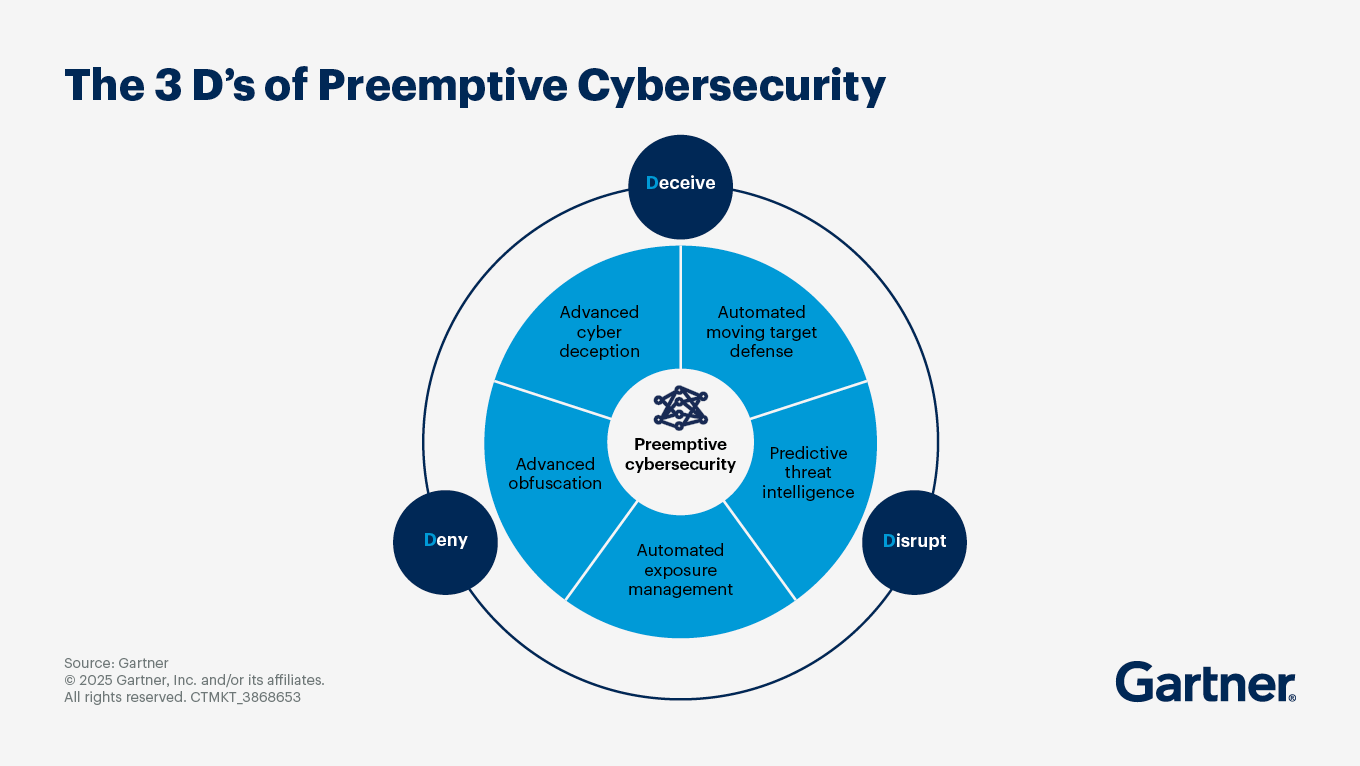

This is a pretty good summary of what’s happening. The only thing that I would add is that while historically, preventative security products have had a harder time than those that are more detection and response (aka firefighting)-focused, in recent years, prevention is starting to get a good amount of traction. Not only are we seeing a new generation of companies emerge, including startups like BforeAI, Aryon, and R6 Security, but even Gartner seems to be putting forward the idea of “preemptive cybersecurity”. Time will tell if we’ll be able to overcome the organizational inertia traditionally associated with preventative and preemptive security measures, but I think when many smart and stubborn people take a shot at something, it’s generally a good sign.

Source: Gartner

This isn’t all about getting a new Gartner category for preemptive security. I think it’s much more about giving security teams permission to prioritize working smarter, getting ahead of the issues, planning for the future, and finding time to pursue the large-scale initiatives every security team I know would like to find time and resources for. It’s about hygiene and a mindset of preventing issues from happening, much more than specific products or product categories.

Looking into the future

It’s been over 20 years since Nelson Repenning and John Sterman published their article, where they explained that nobody ever gets credit for fixing problems that never happened. They were talking about how businesses in general approach decision-making. While none of this was about security, our industry only amplifies the problems seen in other areas of business.

In the coming years, I hope that more security leaders will get the trust credit and political capital to advocate for prioritizing working smarter in their organizations. I see so many CISOs trying to do the right thing but running into internal obstacles that I have no choice but to be optimistic that things will get better. I am also hopeful that we will be seeing more startups coming up with ideas that reinvent old problems and find modern solutions, not merely automating and codifying the old, ineffective ways we have always been doing things. This is the same problem that Tomer Weingarten described as thinking incrementally in our recent episode of Inside the Network. We can all do better as an industry, and I do not doubt that we will.