In security, not every industry problem is a business problem

Looking at the difference between industry problems and business problems and what this means for cybersecurity founders

Nobody can deny that there are many problems in our field. Just attend an industry conference or speak with five security professionals, and it’ll quickly become clear that we have a lot on our to-do list. However, I’ve observed that not all problems are equal, and that of all issues, only a few are business problems. Startups that choose to tackle broad industry problems instead of focusing on specific business problems often struggle. But, there are ways to solve industry problems as well, and I am going to discuss those.

This week, I am trying something different. Instead of a long deep dive, I’m sharing a shorter take on the topic.

This issue is brought to you by… Chainguard.

How much do CVEs cost your business?

Managing CVEs are costly in a variety of different areas. To measure this cost, and the return on investment organizations can expect when utilizing outsourced solutions for CVE management, Chainguard interviewed several industry leaders and quantified the amount of money these organizations unlock in areas like cost savings, increased revenue, faster innovation, and decreased risk.

Two types of security problems

There are two types of security problems: industry problems and business problems. People often treat them as if they are similar, but they aren’t.

Industry problems in cybersecurity

Industry problems are serious technical, philosophical, and operational challenges that security practitioners, university researchers, and standards bodies care about. When you hear things like “as an industry, we should do X”, that’s likely an industry problem. Here are some examples:

Memory corruption vulnerabilities in different protocols

Side-channel attacks in cryptographic algorithms

Lack of DNSSEC adoption

Insecure Bluetooth pairing

Implementing TLS in IoT devices

Formal verification of code

Most discussions about protocols, standards, and making the internet a safer place are great examples of industry problems.

Industry problems tend to sound exciting, meaningful, and impactful. Security professionals who want to make a difference are drawn to these problems because they have a real scale and lead to lasting results. For example, it must feel good to be the architect of the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) 3.0/Transport Layer Security (TLS) 1.0 protocol like Paul C. Kocher or to be an inventor of Secure Shell (SSH) protocol like Tatu Ylönen. These were truly path-defining (no pun intended) innovations. Not all inventors end up reshaping how the internet connects and exchanges information, but all innovations are equally important because they push technology and society as a whole forward.

Business problems in cybersecurity

Business problems are problems that affect a business by impacting its top line (i.e., prevent it from making money), or impacting its bottom line (i.e., cause it to lose money). These are issues that align closely with organizational priorities, regulatory requirements, customer expectations, or profitability, and problems that someone in the organization is incentivized to solve. Business problems have to tie to the goals an executive, such as CEO, CISO, CTO, CIO, CFO, or CPO, cares about and is willing to spend money to achieve. Here are some examples of business problems:

Prevent ransomware so that it doesn’t stop the company from making money

Achieve and maintain PCI or HIPAA compliance to avoid fines and preserve customer trust

Achieve SOC2 to sell to enterprises

Enable secure access for remote employees

These problems are directly connected to money in some form (prevent downtime, prevent fines, acquire and retain customers, etc.). The problems feel niche since scale isn’t quite there, and even the most successful companies may only impact the lives of 500-1,000 corporations, and rarely all of the internet. Moreover, most of these problems are pretty boring from a technical standpoint since they don’t require as much novelty or pushing the boundaries of what’s possible. On the contrary, oftentimes it’s about taking what was already invented and adapting it in such a way that the customer can easily adopt it.

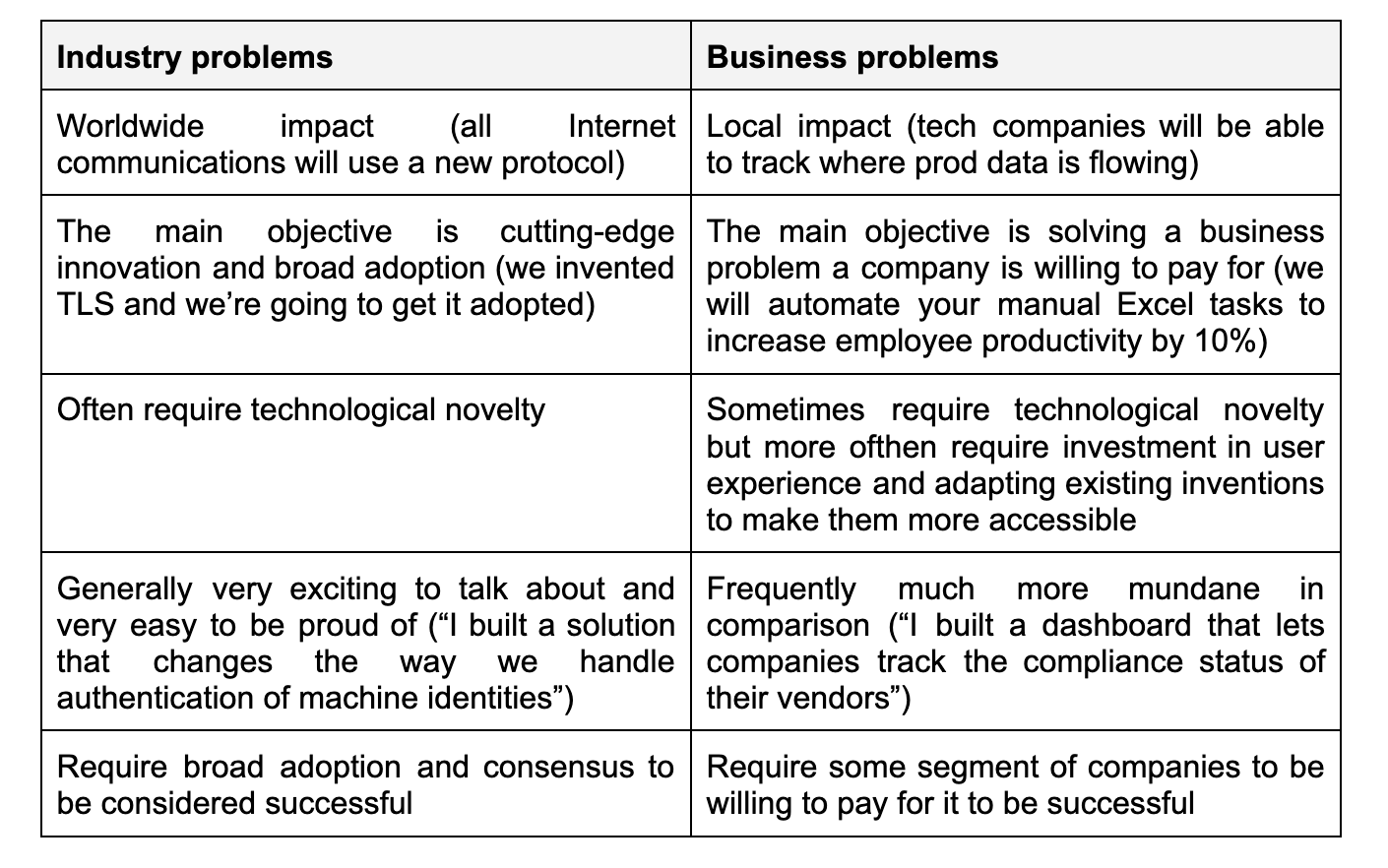

Here’s a quick comparison.

Why this matters

Not every idea that has the potential to improve our industry is a good fit for building a security company around. Many people with great ideas about how to improve security would be way happier championing a new standard, building a non-profit initiative, or an open source project. Security practitioners deeply passionate about advancing security as a discipline can find plenty of ways to spread the word about architectural best practices without having to build a company.

Trying to force an idea into a commercial structure when it doesn't align with a business problem can be pretty frustrating. I’ve met a bunch of founders who were deeply upset that the world doesn’t get their vision, when the reality was that CISOs didn’t have the time to visualize a better future for the industry. Most simply wanted to make sure their company doesn’t get breached on their watch and go spend time with their family after work. On the flip side, some of the most respected people in security never started companies, but they changed the field in ways that no product ever could.

The counterargument to this is the idea that in 2025, the way to achieve lasting impact is to build a company. Taking this path can indeed provide the necessary capital and accelerate the adoption curve, but it comes at the cost that many people don’t understand when they embark on this journey.

On the flip side, many of the ideas that have the potential to make money and become good businesses aren’t going to reshape the industry. Oftentimes, they are about saving the company money by automating manual tasks and making people more productive, or checking the right compliance boxes so that the company can sell products and make more money.

Technical founders sometimes dismiss ideas that don’t seem to have much technological depth as “boring” to pursue innovative tech, only to then look around and realize that others make more money by selling what looks like pretty basic tools. Such is the nature of business: people don’t buy what’s cool, they buy what solves their problems, and most problems are actually pretty basic.

There are always going to be exceptions (kind of)

For every rule, there are always exceptions, so there will always be players who are so obsessed with solving an industry problem that they dare to reimagine the problem space entirely. At least, that’s how we like to think. The idea is that some companies and founders reshape markets, challenge assumptions, introduce new mental models, and educate the business on why a problem they see is worth caring about. They are the ones that create new categories or significantly expand old ones.

There is no denying that this is possible, but for it to happen, there still needs to be a reason why businesses should care. There may not have been an EDR category before CrowdStrike and Cylance, but CrowdStrike and Cylance didn’t invent the problem; they just made it visible for businesses that didn’t know it existed. In other words, they had to explain to CISOs why their specific company is going to suffer a big way if they don’t act, not why the whole industry should do something differently.

There are times when something that starts by solving an industry problem turns into a solution to a business problem. I usually see it happen in 2 ways:

A new technology appears to solve an industry problem which enables the creation of a solution to a business problem. For example, all the applications of WireGuard and eBFP.

An open source project starts to solve something that looks like an industry problem but in the process it reveals and solves a business problem.

It all comes down to incentives

It all comes down to incentives. Always. Adrian Sanabria put it really well in his comment to one of my LinkedIn posts: “Definitely one of the biggest challenges in our industry - figuring out incentives for the critical stuff that aren’t business problems. Another challenge: some of these industry problems can’t be solved by a vendor, because there’s no clear way to monetize it, or the monetization strategy would compromise the goal. So we have to hope that MITRE, CISA, or some volunteer effort tackles it.” That is indeed a problem because security as an industry problem is essentially a public good. As with everything that has to do with public goods, unless there are activists who care about the cause, very little is going to happen. Hence why, for the time being, I think we’ll have to do what Adrian said - “hope that MITRE, CISA, or some volunteer effort tackles it”.

Well said and this is a key point for aspiring and existing founders to take heed of.