Immigrant background is a perfect crucible that forged many successful cybersecurity founders

Nir Zuk of Palo Alto Networks, Ken Xie of Fortinet, Jay Chaudhry of Zscaler, Dmitri Alperovitch of CrowdStrike, Ashar Aziz of FireEye, and Tomer Weingarten of SentinelOne are some of the examples

Over the years I’ve observed that many accomplished people had a crucible - something that forged their character, forced them to do more, gave them the energy to keep going, and eventually led to their success. Some grew up poor and had to work incredibly hard to build themselves up and escape poverty. Others were raised in rough neighborhoods and were literally forced to fight for their own survival. There are also those who had to battle an illness or a disability, and who had to work exponentially harder to succeed in life.

People who had to overcome adversity and rise despite the odds often achieved success and rose to the top of their area, be it by becoming military generals, academics, inventors, or entrepreneurs. Being a serial founder is another kind of crucible that is known to breed success. Suffering makes character. It helps people focus and pursue their aspirations with everything they’ve got.

In this piece, I am looking at one particular type of crucible that forged a large number of successful cybersecurity startup founders, - immigrant background. The vast majority of successful companies were started in the US by US-born founders. And yet, immigrants have played an outsized role in shaping the present and the future of the industry.

Immigration is always a controversial topic. I’m not looking at the merits of immigration, the ways it impacts countries and economies, and other complex matters. I’m not qualified to make any big assertions - I’ll leave that to people much smarter than me. Instead, I am talking about the fact that an immigrant background is a perfect crucible that forges strong successful cybersecurity founders.

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Over 2,100 copies of my best selling book “Cyber for Builders: The Essential Guide to Building a Cybersecurity Startup” have been delivered by Amazon so far. This book is unique as it talks about building cybersecurity startups. It is intended for current and aspiring cybersecurity startup founders, security practitioners, marketing and sales teams, product managers, investors, software developers, industry analysts, and others who are building the future of cybersecurity or interested in learning how to do it.

Israeli founders: IDF and a continuous supply of entrepreneurial talent

Before we dive into our main topic, I would like to have a brief look at Israel and recap what made it so successful in launching many successful cybersecurity startups. Let me start by saying that there is no one reason; as discussed in my piece on Israel, this includes:

Government support which enabled the rapid growth of Israel as a startup nation.

Large amounts of capital available to support Israeli entrepreneurs and their ideas.

Support systems and resource hubs built by the country’s leading VC firms.

Strong angel network fuelled by the desire to support one’s networks and pay it forward.

However, none of this would be possible without a continuous supply of entrepreneurial talent, and the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) which plays a key role in its formation.

Israel has a steady pipeline of entrepreneurs which looks like the following:

From a young age, kids are raised in a culture of self-confidence, audacity, or daring (in Hebrew, it's called ḥuṣpāh).

In schools, there are programs that incentivize risk-taking and entrepreneurship.

Since Israel has mandatory military service, the IDF gets to pick the best and the brightest from the whole country and assign them to different military units, many of which focus on developing leadership skills, critical thinking, and calculated risk-taking.

The United States possesses much more superior cyber warfare capabilities than Israel but that should not be a surprise: the US spends close to $2 trillion on the Department of Defense (DOD) alone, while Israel, being a much smaller economy, invests in its military about 7 times less. In both countries, the military offers an incredible ability for service members to build their character and develop technical proficiency in cybersecurity. No private sector company is ever going to tackle the technical challenges so advanced as the NSA in the US or Units 8200 or Matzov in Israel, and no service provider will give its employees as much freedom as these agencies.

The focus on entrepreneurship and the idea that military service is something temporary are some of the core factors that distinguish the elite IDF units from US agencies such as the National Security Agency (NSA). The top US cybersecurity practitioners who join the NSA tend to stay there for decades; if they leave, it is typically to retire into cybersecurity consulting, and sometimes - to become CISOs at large organizations. There are exceptions to this rule, but they aren’t as common. The Unit 8200 alumni, unlike their US counterparts, usually leave in their late 20s to join their friends in a successful startup or seek to build a path-defining product company on their own.

Just under 10 million people live in Israel (four times less than in California). The population of Tel Aviv, the country’s capital where most of the startup activity is concentrated, is under 500,000 (half of that of San Francisco). Such concentration of people and talent in one place means that everyone in the country is connected - if not directly, then through one or two introductions. This proximity and connectedness mean that most people in tech know someone who started and successfully exited a tech startup.

The combination of the culture, the bonding and leadership experience from the military, and the exposure to success stories of ordinary people create a steady pipeline of new entrepreneurs. While Israeli founders are known to run into challenges when looking to scale their companies into large global corporations, the art of starting and growing successful startups has been truly mastered here.

US cybersecurity founder pipeline problem

Evolving state of the cybersecurity ecosystem

The United States does not have a similar pipeline of cybersecurity startup founders. Here, security founders typically come from diverse backgrounds which tend to be linked to the kinds of problems they are looking to solve.

Historically, founders of cybersecurity services often came from hacking, and later, penetration testing backgrounds. As the regulations caught up, slowly people with experience handling compliance also started establishing their own businesses, although admittedly they were more focused on governance, risk, and compliance (GRC) and not hands-on security. Cybersecurity product founders, on the other hand, frequently had strong backgrounds in information technology (IT) and networking. These two fields were where most security practitioners started their careers before cybersecurity emerged as an independent discipline. Regardless of their training or area of expertise, what united many of the product builders was their love for open source. Not just because security knowledge was shared in communities of people which overlapped with open source contributors, but also because the very act of building security solutions was usually a community initiative. Only after some time, did a selection of these projects “productize” and become private companies.

It wasn’t product or service founders, but technologists with a passion for security who built a lot of the tools and infrastructure we are relying on today, and established concepts and knowledge areas that comprise the security body of knowledge.

Fast forward to today, and a lot has changed. First and foremost, we are talking about security as an industry, as a discipline, and as a profession. As an industry, security has an evolving ecosystem of players such as vendors, investors, distributors, analyst firms, and regulators that influence the behavior of different market participants, enable value creation, and allow companies to access the solutions they need. As a discipline, security is without any doubt maturing and becoming better accepted and better understood. A growing number of professional conferences, events, and communities, supercharged by the power of the internet and social media, are making security more accessible and facilitating the distribution of knowledge globally. As a profession, security is becoming more and more complex, and with that, more specialized. One can no longer hope to cover all the possible areas of security. Moreover, security is formalized as a profession, with training programs, professional designations, trade groups, and other attributes.

What has also changed is what it means to solve security problems. In the past, if one wanted to tackle an important problem area, they would either look to start offering services (full-time security roles were scarce) or build an open source project on the side while keeping their main job in networking, IT, or adjacent areas. Fast forward to today, and there are many more options for security practitioners to make a difference. They can join a security team and work on the Security Operations Center (SOC) side of the house, they can become engineers and focus on application security, start their own product or services firm, and so on. It has become both easier and harder to find a path in security. It’s easier because the knowledge one needs to get started is out there and most of it is available freely for those who know where to look, the need for security is broadly understood, and a large number of companies are hiring security practitioners. Moreover, knowledge about starting companies has also been democratized, to a large degree thanks to business programs, experienced entrepreneurs willing to pay it forward as mentors and advisors, and the role of investors. However, it has also become increasingly harder to compete and achieve meaningful differentiation, for both companies and security practitioners looking for new roles.

New bar for cybersecurity startup founders

In today’s world, building security products is much harder than before. There are many reasons why that is the case:

Gone are the times when there were less than ten companies competing in the same market. Before, demand for security solutions wasn’t there, so every founder had to invest resources into educating the market. Fast forward to today, and there is so much information that it has become nearly impossible for buyers, investors, analysts, and industry insiders to separate the signal from the noise.

Speed of execution has become critical. Because of the number of competitors, it is no longer possible to move slowly and to take a long time to learn one’s surroundings before starting to build and sell.

Differentiation is very hard to achieve. Due to the number of homogenous, poorly differentiated products on the market, founders have to be confident that they will be able to stand out from the crowd.

To build a security product in 2024, founders need to a) have experience doing security, b) have experience building products, and c) be interested in doing the work needed to build a business. Unlike in Israel, where the IDF and the local startup ecosystem create a supply of tech entrepreneurs with all three components in place, in the US the overlap between these three areas critical to success is rare. This is why the US has a cybersecurity founder pipeline problem.

Cybersecurity founder pipeline problem in the US

There are two main dimensions for discussing the cybersecurity founder pipeline problem in the US: skills and mindset.

On the skills side, the challenge is that the overlap on the builder-practitioner Venn Diagram is quite rare. Most security practitioners are not builders, and most software engineers don’t know much about security. Being a practitioner without the ability to build makes it harder to start a new company, and slows the speed of shipping code. On the other hand, companies started by software engineers without a good understanding of security rarely solve the right problems, and equally rarely solve them the way security buyers are looking for.

In the US, people who have both skill sets usually work as security engineers or software engineers. Because they are rare, they also get compensated pretty well, especially if they join a FAANG company, or a hot venture-backed, cloud-native security startup. People who work in the Bay Area making $250,000-$750,000 or more somewhere at Google or Meta, have little reason to take risks, give up their lifestyle, and start worrying about paying their mortgage while increasing their stress level 20X plus.

Security engineers and software engineers with a passion for security are best positioned to reshape the industry, bring new thinking to security, and build the future of cyber defense. What is lacking is the entrepreneurial mindset. Security & software engineers in the US can have great compensation and great financial and career outcomes without signing up for the crazy roller coaster building a startup is. Unlike their Israeli counterparts who see their classmates, friends, and colleagues build companies left and right, they tend to not be as restless and hungry. In order for security engineers to take risks and give up their successful and well-paying careers, they need to be hungry. The challenge is that the more experienced they are, the more likely they are to be comfortable, the more likely they are to have a mortgage and other obligations, and the less likely they would be willing to go back to eating ramen and struggling to pay their rent. The overlap between experienced and hungry security and software engineers is quite small but that’s exactly where the magic happens.

Then, there’s the business side. Most engineers aren’t interested in the business of security, go-to-market, sales, marketing, etc. Those that are, are either a) so deeply entrenched into playbooks & how things have “always been done” that they struggle to think differently, or b) so much against all the practices they've seen that they lose connection with reality and insist on pushing forward approaches that don’t bring results.

All this creates a paradox: while the number of security practitioners in the US is estimated to be over 10 times higher than in Israel, it is Israeli security startups that are making the noise in the industry almost daily. If the US wants to continue being the leading cybersecurity startup ecosystem, it needs to find a way to encourage more people in the country to take risks and build security companies. In other words, it needs to re-establish the cybersecurity founder pipeline.

Solving the US cybersecurity founder pipeline problem

The need to stay hungry

Steve Jobs once said, “Stay hungry. Stay foolish. Never let go of your appetite to go after new ideas, new experiences, and new adventures”. This quote remains as relevant as ever in the world of cybersecurity.

The truth is that people who have the highest chance to reshape the way security works and solve the toughest problems in the industry aren’t the most gifted, the most talented, or even the best security engineers. They are those who are driven by a sense of purpose, a sense of mission, and a sense of achievement. They are hungry. This doesn’t mean being hungry for money (although people who make an impact at scale should certainly be fairly compensated for their work). What it means is being hungry for impact, scale, growth, achieving new horizons, and making a dent in the industry.

This brings us to a question - who in cybersecurity is hungry? Not just hungry for knowledge, or professional growth, but so hungry for large-scale impact that they are willing to sacrifice the comfort and push a boulder up the hill, for many years?

Immigrants eager to build better lives for themselves and their kids are hungry. Israeli founders seeking scale of impact are hungry. People new to the Bay Area determined to make a dent in the world are hungry. Young students who leave high-paying jobs to join Y Combinator are hungry. Aspiring security practitioners are hungry. People volunteering their time to organize events, speak, teach others security, and contribute to open source projects are hungry.

Immigrants to the US have had an outsized impact on cybersecurity

Of all the categories of people based in the United States, one stands out the most to me. I am talking about immigrants, people who moved to the US from other countries. This rarely mentioned category of people has had an outsized impact on cybersecurity. Although few people these days like to talk about immigration, the fact of the matter is that for centuries, the US has been able to attract the best and brightest from all over the world.

Here is a fact that may surprise many people: although the US is the largest market for cybersecurity companies, many of the most successful US-based and US-focused security companies were built by people born or living outside of the US.

Nearly half of public cybersecurity companies listed on the US stock exchange were co-founded or founded by people born outside of the US. This list includes Check Point, CyberArk, CrowdStrike, Fortinet, Palo Alto Networks, Qualys, SentinelOne, Trend Micro, Zscaler, BlackBerry, Cloudflare, and Sumo Logic. One of the three private security companies valued at over $10B, Wiz, is founded outside of the US (the other two are Proofpoint and Kaseya). 8 out of 12 companies valued at over $5B were co-founded or founded by people born outside of the US (Tanium, StarkWare, Snyk, Netskope, Lacework, Fireblocks, 1Password, and Mimecast).

This list can go on and on. Granted, not all of the foreign nationals who ended up building path-defining companies with a large presence in the US did so while living here, and not all ended up moving. But, many did. Israelis, Indians, British, Canadians, Taiwanese, Chinese, Iraqis, Pakistani, Russians, Ukrainians, Romanians, and people born in other countries built a huge chunk of what we think of as cybersecurity in the United States.

Not only that, but their contributions have shaped what we think of as security as a discipline. One of the countless examples is Ashar Aziz and FireEye, the company he founded. As Sid Trivedi of Foundation Capital rightfully pointed out in comments to my LinkedIn post on this topic, “Ashar changed the way we think in cyber. He was the first to really push and ask the question “What about post breach? How do we detect and respond if a bad actor gets through the firewall?”.

Over the years, the importance of foreign-born talent to US security has only grown. Nir Zuk of Palo Alto Networks, Ken Xie of Fortinet, Jay Chaudhry of Zscaler, Dmitri Alperovitch of CrowdStrike, Ashar Aziz of FireEye, and Tomer Weingarten of SentinelOne are some of the examples of immigrants who had a tremendous impact on security in the US and globally.

More broadly, a large number of security startups based in Silicon Valley were founded by immigrants from India, and a good number of security companies in New York and Boston were founded by Israelis.

Factors that make immigrants great entrepreneurs

There are many factors that make immigrants great entrepreneurs.

Immigrants have experience building 0 to 1

It takes a certain kind of person to leave their family and friends from their home country and try and make it in one of the biggest economies in the world. Immigration equips people with experience building 0 to 1 and everything this journey brings including setbacks, failures, doubts, mistakes, endless pivots, and continued learning. They are building their lives, not just products.

Immigrants know how to handle failure and rejection

Immigrants are adept at handling rejection. It is nearly impossible to find an immigrant who didn’t struggle to re-establish themselves in the new society - because of their backgrounds, accents, cultural differences, or any other reasons. It’s hard to judge people as we always prefer what’s familiar and what we know. The important part is that failure and rejection build character. Immigrants just wouldn't survive if they didn't try, fail and try again.

Immigrants are focused and used to making sacrifices

Immigrants know that achieving big goals is impossible without making great sacrifices. It also requires focus - the kind of focus that is only possible when one learns to recognize and say no to distractions, 24 hours per day, 7 days a week.

Immigrants don’t know how to stop

Immigrants are always on the move. They simply don’t know how to stop, how to accept what they have, and how to sit back and rest. They are always thinking, planning, and executing. They are always pursuing some passions, personal projects, new learnings, and ambitious goals. At first, this starts as a necessity, as a drive to succeed, and over time it becomes who they are.

Immigrants are scrappy and resourceful

Immigrants know how to do a lot with little. They know how to survive on $500 per month, they know how to ask for help, and how to make the most of any resource they have access to.

Immigrants are risk-takers

It takes a special kind of mindset to leave the country where you were born and move to another side of the planet, with no friends, no support systems, no jobs, and barely any money in your pockets. Immigrants are not afraid of taking risks. They take calculated risks and know when to bet big and when to be patient.

Immigrants have enormous patience

It takes decades for new immigrants to establish themselves in the new society, and it can take many years before they can reach the same level of income and social status they had in their countries. But, because they know they are playing a long-term, strategic game, they have a lot of patience and are able to weather as many storms as needed on their way to the destination.

Immigrants know they are in it alone

Immigrants know that they cannot count on their friends and family for help. They know that success depends fully on themselves, on their ability to plan and execute, on their ability to develop a prepared mind and do what it takes to succeed.

Looking outside of security

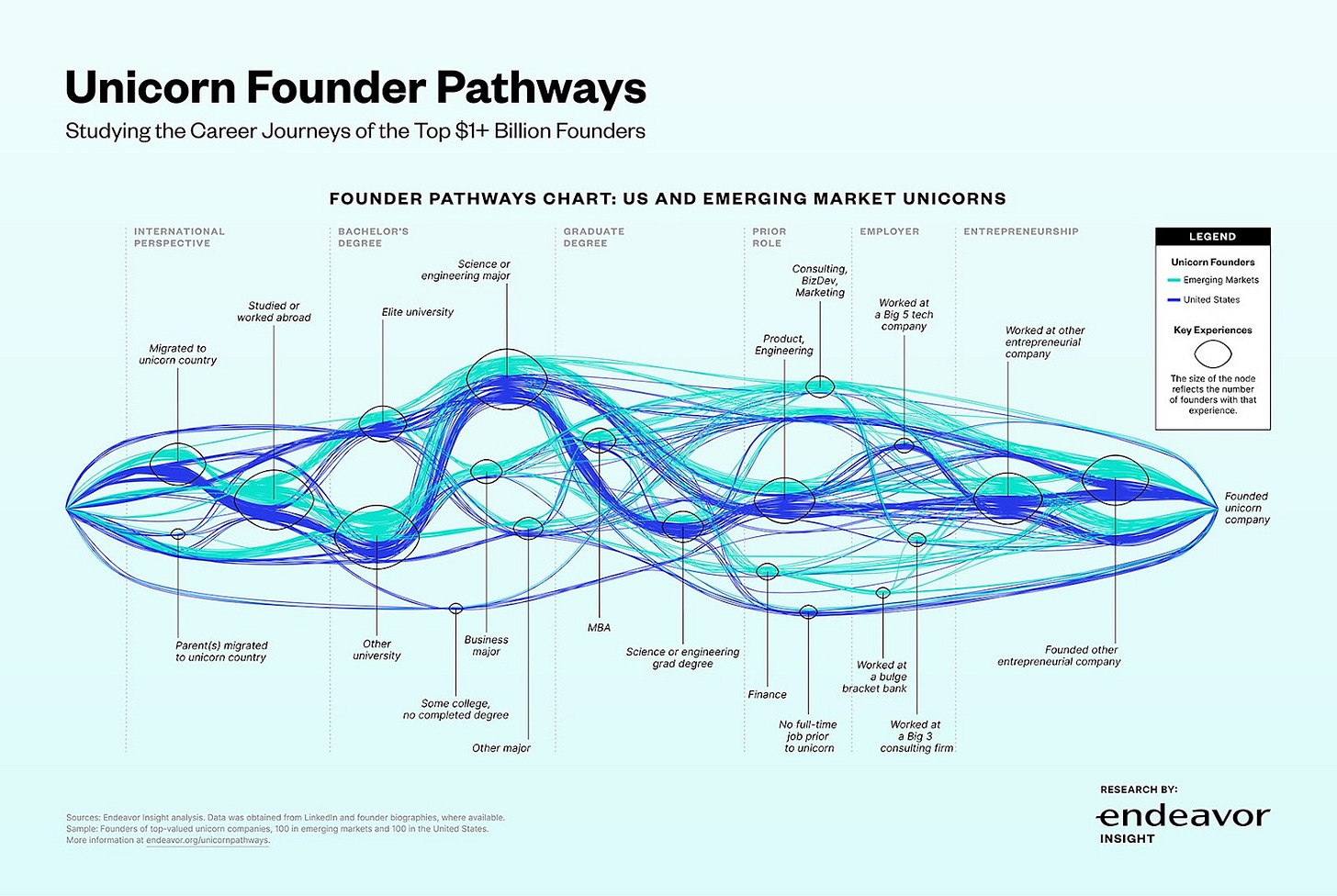

The data outside of security shows similar patterns as well. Endeavor Insight research team compared the pathways between 100 of the top unicorn founders in the United States and 100 more in key emerging markets. Here is one of their most important conclusions:

This is not surprising. For anyone looking to get a better understanding of where unicorn founders come from, I highly recommend digging into Endeavor's research findings.

Source: Endeavor Insight

Source: Endeavor Insight

Closing thoughts: technical security practitioners & software engineers with immigrant backgrounds are well-positioned to reshape the industry

Not all brilliant security practitioners are, will be, or should be starting security companies. We need people who can work on security teams, teach others what they know, and do the work that allows them to fulfill their potential. However, security engineers, architects, and technical security practitioners who choose to build their own companies will have the advantage over those who do not fundamentally understand the industry and the problems that matter.

Similarly, not all immigrants working in cybersecurity are, will be, or should be starting security companies. However, those that do, are well positioned to succeed because the skills they had to build while trying to establish themselves in a new country have given them the kind of MBA of hard knocks that is invaluable for any entrepreneur. Immigrants, in their majority, are people who have something to prove and cannot rest, settle, or sit still. Who had to strategize their life and then execute. Who start with nothing and make something of themselves. Successful founders go through a crucible of a kind, and immigration for many reasons is a perfect school of life. They had to learn how to sell themselves, how to outwork, outsmart, and outpersist others. They overcame adversity, and that’s how the character is built.

All this combined makes it easy to conclude that the percentage of people born outside the US who will have an outsized impact on the nation’s security will continue to grow. And, that technical security practitioners who immigrated are likely to continue reshaping the industry, both in the US and globally. For obvious reasons, immigration is not the only way to build the skills one needs to succeed as a founder, but it’s a very effective one.

Yes. We immigrants are always live by hunger. Rejections and failures are part of the journey.

You had me at "Suffering makes character"