20 years of cybersecurity consolidation: how 200 companies became 11

The most comprehensive illustration ever made of how our industry has consolidated over the past 20 years, showing how 200 companies turned into just 11.

I am attending Black Hat this week, and in many conversations I’ve had so far, one theme keeps coming up: consolidation. Obviously, this article was written before the conference, but the timing couldn’t be better. In this piece, I am going to apply a framework (developed years ago by people far smarter than me) to our industry and explore what consolidation means for us, how far along are we, and what we should expect for the next decade. Most importantly, I’ll share what I believe is the most comprehensive illustration ever made of how our industry has consolidated over the past 20 years. You’ll see in great detail how in just two decades, nearly 200 companies consolidated into just 11.

This issue is brought to you by… Vanta.

Level-up your security with confidence

As you scale your business, security needs to be more than a checkbox—it should be the foundation for customer trust and long-term growth.

Vanta’s Trust Maturity Report helps you benchmark your security program against your peers so you can level up your security with confidence.

Aligned to the NIST CSF maturity tiers, this report uses customer insights and aggregated, anonymized data from Vanta’s 11,000+ customers.

Vanta helps growing companies achieve compliance quickly and painlessly by automating 35+ frameworks—including SOC 2, ISO 27001, HIPAA, CMMC, and more. And with Vanta continuously monitoring your security posture, your team can focus on growth, stay ahead of evolving regulations, and close deals in a fraction of the time.

See what your security program may be missing by downloading the report.

Four stages of industry consolidation

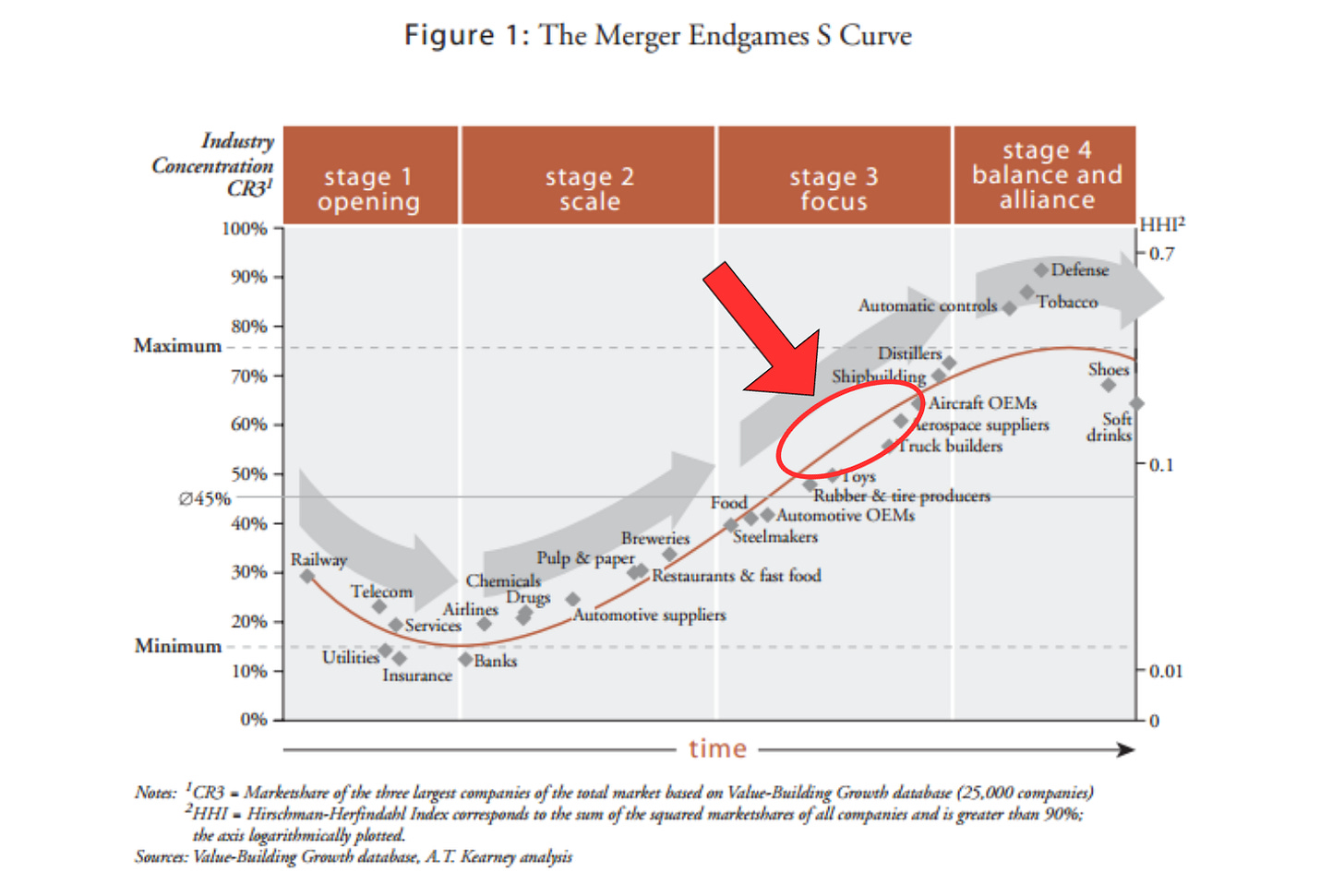

Twenty years ago, Harvard Business Review published a study that looked at more than 1,300 major mergers. The authors, Graeme K. Deans, Fritz Kroeger, and Stefan Zeisel, found that every industry, after it emerges or becomes deregulated, follows the same path which they called the four stages of consolidation: opening, scale, focus, and balance and alliance. They argued it typically takes about 25 years to run the full course, though future industries would move even faster.

Stage 1: Opening

This is when a new industry takes shape. First movers rush to gain an edge by building scale, expanding globally, and protecting their ideas. The goal is to establish barriers before competitors can catch up.

Stage 2: Scale

Next comes the race for growth. At this stage, the top three players usually control between 15% and 45% of the market. As the HBR authors explain, “Because of the large number of acquisitions occurring in this stage, companies must hone their merger-integration skills. These include learning how to carefully protect their core culture as they absorb new companies and focusing on retaining the best employees of acquired companies. Building a scalable IT platform is also crucial to the rapid integration of acquired firms. Companies jockeying to reach stage 3 must be among the first players in the industry to capture their major competitors in the most important markets and should expand their global reach”.

Stage 3: Focus

At the focus stage, competition heats up, and we start seeing mega‑deals as the strongest players fight for dominance. Typically, five to 12 major companies remain, and the top three control up to 70% of the market. Startups face a choice: to get acquired or crushed.

Stage 4: Balance and Alliance

Finally, consolidation slows. Once the fourth stage is reached, the top three companies can own as much as 70% to 90% of the market, and for the rest of the players, the game is basically over - they are either crushed or become absolutely insignificant and unable to achieve any meaningful scale. Industries like tobacco, soft drinks, and defense have been living in this phase for over 2 decades.

The HBR article ends with one critical learning: “Ultimately, a company’s long-term success depends on how well it rides up the consolidation curve. Speed is everything, and managers’ merger competence is paramount, particularly during the middle stages of consolidation. Companies that evaluate each strategic and operational move according to how it will advance them up through the stages. Those that capture critical ground early and move up the curve the fastest will be the most successful. Slower firms eventually become acquisition targets and will likely disappear. Most companies simply won't survive to the endgame by trying to stay out of the contest, or worse, by ignoring it”.

For anyone interested in how consolidations happen, I highly recommend reading the original article.

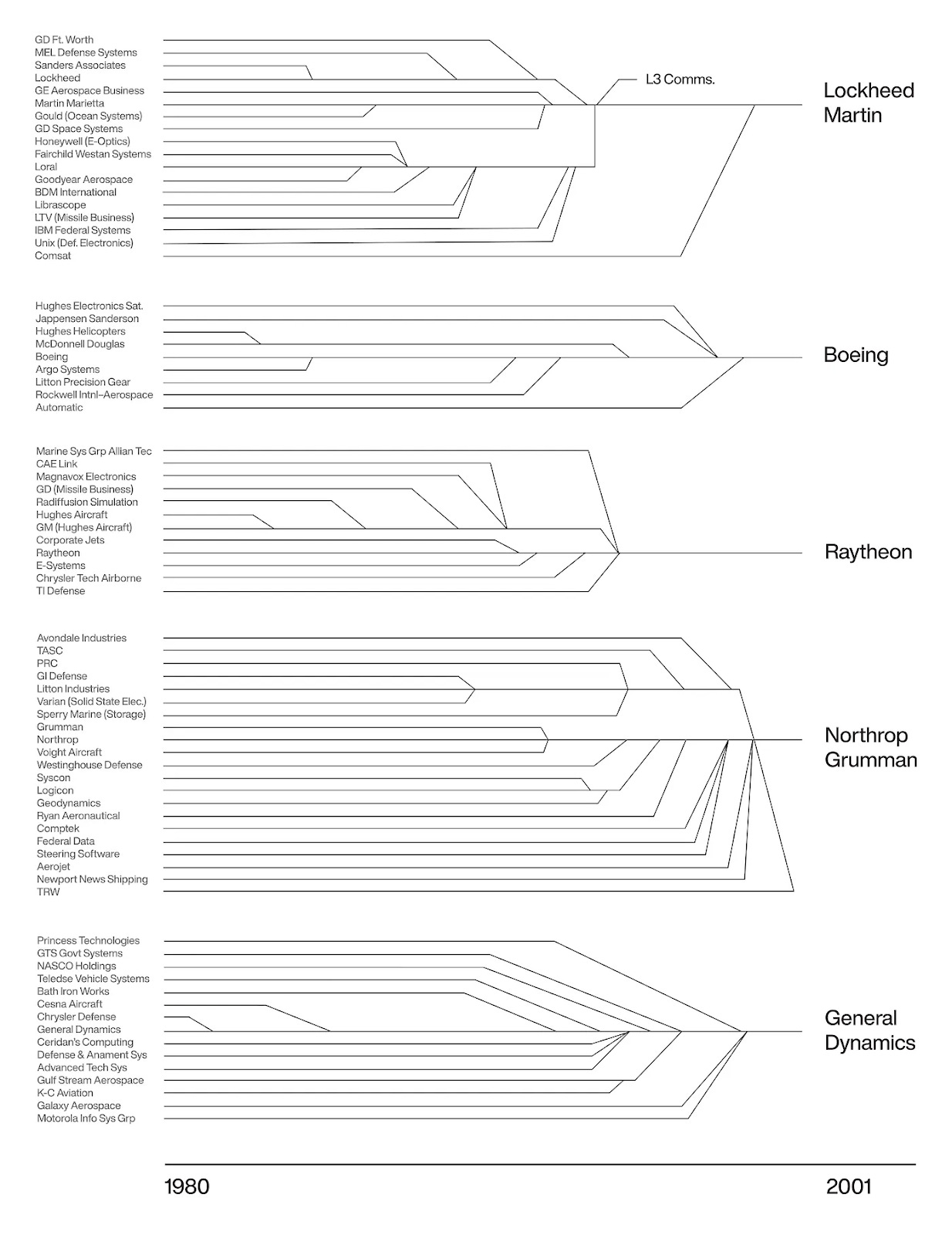

Defense industry consolidation

A prime case study of how industry consolidation can unfold is the defense industry.

Back in 1993, then U.S. Defense Secretary Les Aspin hosted a dinner with senior leaders of America’s largest defense contractors, which went down in history as the Last Supper. The message was blunt: Cold War budgets were gone, and the Pentagon could no longer support the sprawling network of primes and subcontractors that had grown during the arms race. With fewer contracts and tighter budgets, the DoD made it clear to industry that widespread consolidation was not only expected but necessary for survival.

Those who attended the dinner got the message. In the decade that followed, the defense sector saw one of the largest waves of mergers in modern U.S. industrial history. Lockheed merged with Martin Marietta to form Lockheed Martin. Northrop acquired Grumman to become Northrop Grumman. Boeing absorbed McDonnell Douglas, while Raytheon consolidated with Hughes’ defense units. Hundreds of mid‑tier and specialty suppliers were folded into larger conglomerates, creating a smaller number of dominant prime contractors with the scale to sustain advanced R&D programs and handle massive, complex procurement projects.

This consolidation reshaped the U.S. defense industrial base. On one hand, it created more stable and financially secure primes capable of investing in next‑generation technologies and competing for multi‑billion‑dollar programs. On the other hand, it reduced competition, leaving the Pentagon with fewer options and increasing dependency on a handful of “too‑big‑to‑fail” firms. The long‑term effect was a defense sector that became more concentrated, less dynamic, and more reliant on an ecosystem of specialized subcontractors feeding into a small core of giants, a structure that continues to shape U.S. defense procurement today.

Many of you have probably seen this picture, and if you haven’t, I am sure you’ll find it interesting.

Image source: Defense Industry Consolidation, Anduril

If you want a deeper dive into the evolution of defense tech, check out this article by Packy McCormick.

Cybersecurity is long past its “Last Supper” moment

The cybersecurity industry is undergoing a consolidation wave that is moving far faster than many realize. This isn’t at all about CISOs wanting fewer tools as much as some would like to think - the changes are happening at the macro level.

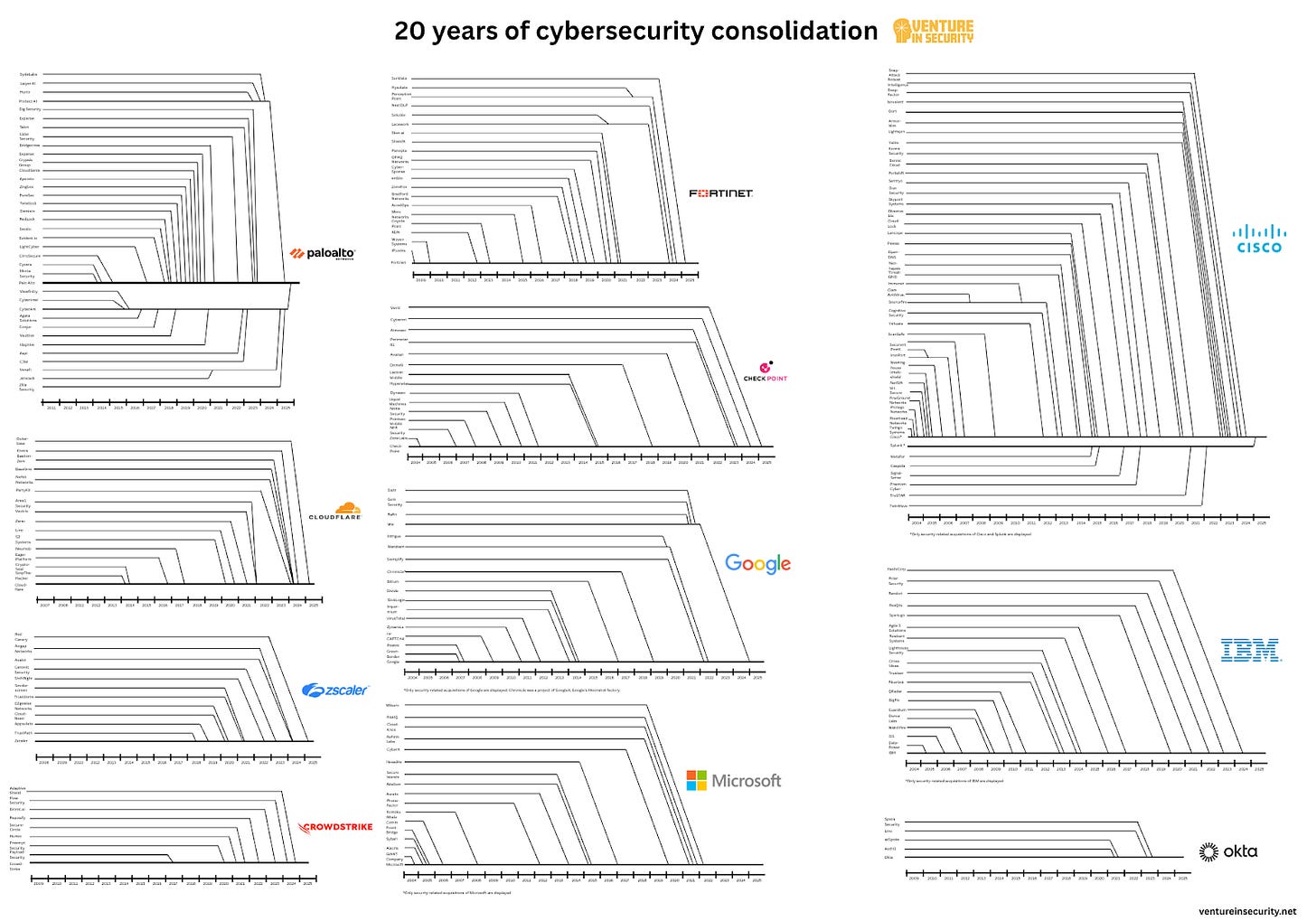

Over the past two decades, we’ve seen thousands of well‑funded startups enter the market, driven by the rising number of breaches, growing customer demand, regulatory mandates, and a seemingly endless flow of venture capital. Fast forward to today, and it’s clear that the vendor landscape is increasingly dominated by a dozen of giants like Palo Alto Networks, CrowdStrike, Fortinet, Zscaler, Cisco, Microsoft, Google, IBM, Cloudflare, Check Point and Okta. These companies aren’t just building internally; they have turned acquisitions into a continuous R&D pipeline, absorbing two hundred startups to accelerate innovation and lock in market share.

To understand what’s happening, it helps to apply the four stages of consolidation framework to cybersecurity.

Stage One: Emergence

Pinpointing the true beginning of cybersecurity as an industry is tricky because it doesn’t quite coincide with the birth of cyber as a practice. Some people might trace the beginnings of the cyber market back to early firewall vendors, Check Point (1993), McAfee (1987), or even Sophos (1985) founding, and others to the rise of the commercial internet and the first major attacks. I think each of these arguments is valid. The very beginnings of our cyber market date all the way back to the mid-1980s. This was the formative time, and it happened at the same time as the birth of the CISO role (the first person to hold the title of Chief Information Security Officer was Steve Katz, who was appointed to the role at Citicorp in 1995).

All that said, what we know as “modern cybersecurity” was born in the 2000 to 2010 decade. This was when companies like Palo Alto Networks (2005), Fortinet (2000), Zscaler (2007), Cloudflare (2009), Okta (2009), Proofpoint (2002), Mimecast (2003), Tenable (2002), Qualys (1999), CrowdStrike (2011), KnowBe4 (2010), and many others were started. These firms did exactly what Harvard Business Review researchers suggested: built for scale, expanded globally, and amassed strength fast enough to become too big to fail. Everything before this era laid the groundwork, but it was this cohort that truly transformed cybersecurity from a niche concern into a global market.

Stage Two: Scale

The 2010s unleashed a massive expansion. The number of cybersecurity startups exploded, with more than 5,000 companies competing for CISO attention today. This decade was marked by an impressive pace of acquisitions. The already established players like Palo Alto, CrowdStrike, Cloudflare, and others honed the craft of M&A integration (though not without missteps and some did it better than others). The industry of the past 5-7 years has been defined by aggressive growth, fueled by both capital and consolidation. The pandemic as well as the increase in ransomware helped supercharge this growth as well.

Stage Three: Focus

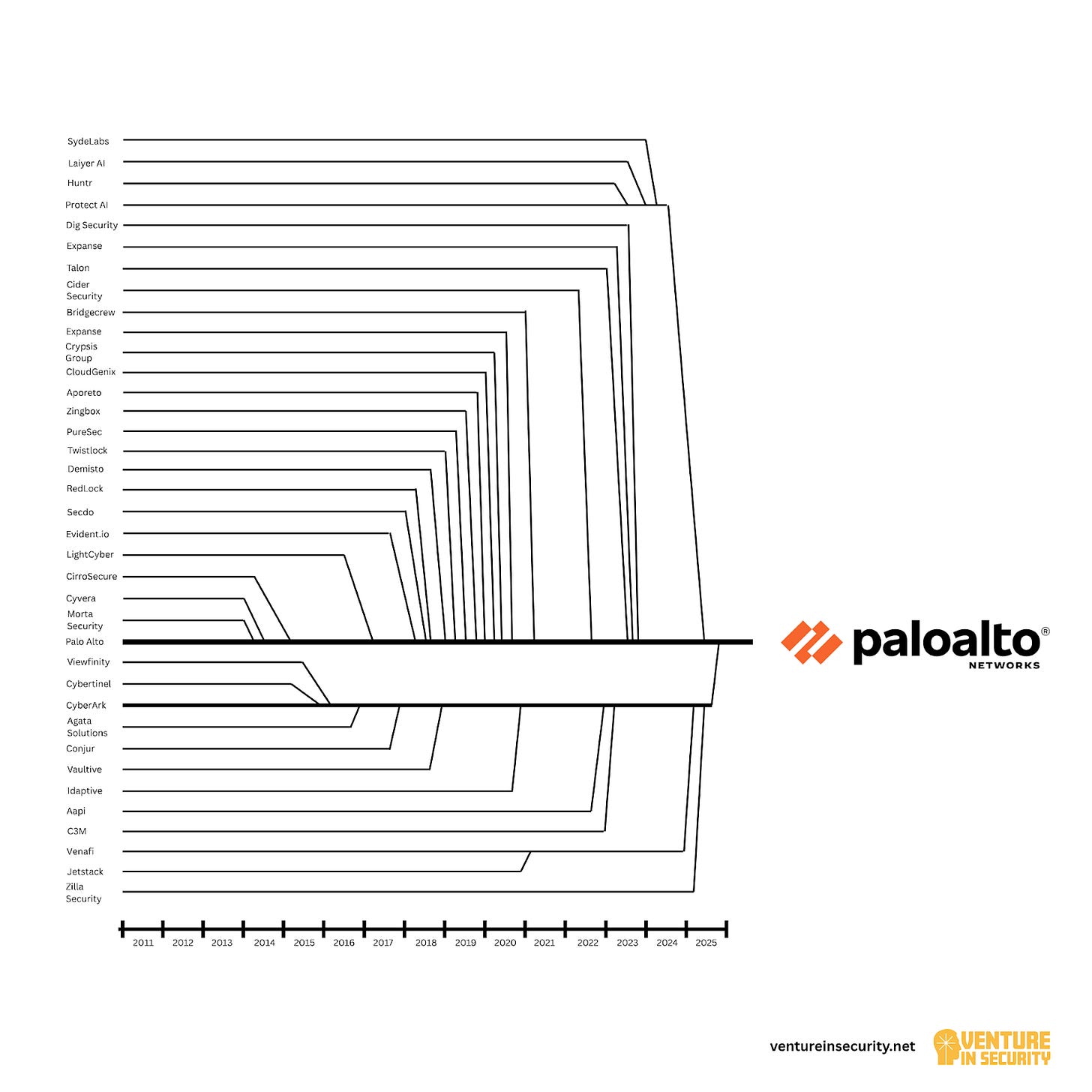

Today, I believe we have crossed from scale to focus. The signs are impossible to ignore. The list of top players has crystallized: Palo Alto, Cisco, CrowdStrike, Zscaler, Cloudflare, Okta, Fortinet, Microsoft, Sophos, Google, IBM, and Check Point. Mega‑deals are increasingly common: Google’s acquisition of Wiz, Cisco’s purchase of Splunk, and the recently announced Palo Alto’s acquisition of CyberArk are just a few examples. What looks like uncharted territory is actually very much what’s expected at the focus stage. For startups, the dream of building a standalone giant is fading; the most realistic outcome is acquisition, and this reality is fueling the very M&A cycle that accelerates consolidation. Even the industry’s best-funded scaleups, like Wiz, Cyera, etc., are all, in my opinion, built as acquisition targets from day one.

Here is what many people don’t realize: two decades after the rise of the modern cyber industry, we are not in “just another cycle” of consolidation. I used to believe that as well, but having learned more about the space, I am convinced that we are in the middle of a once‑in‑a‑generation shift, the third stage of consolidation, that will only be fully understood in hindsight a decade from now. Startups are no longer primarily category creators; they’ve become the de-facto R&D arms of the giants (and nobody has executed on this better than Israel). The power centers of the industry are set, the acquisition playbooks are refined, and the battle ahead is not about who will emerge, it’s about who will survive.

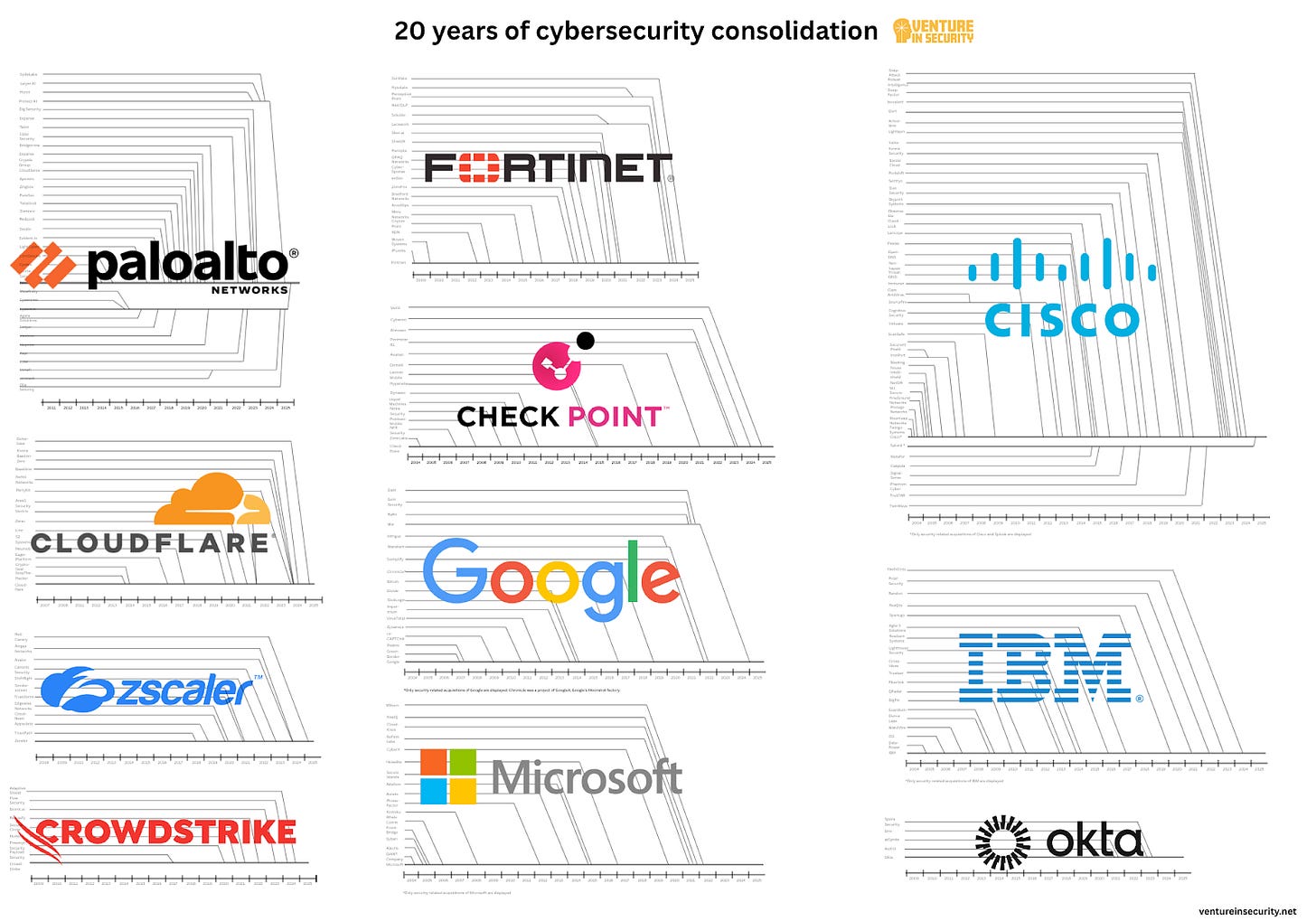

Cybersecurity consolidation in a single chart

Here is a chart I put together to show how we arrived at this moment. If you compare it with the picture showing the consolidation of the defense industry at the top of this article, you will see what I see. Cybersecurity is repeating the same destiny, not because of coincidence, but because it is following a natural cycle of industry maturation and consolidation.

What makes this especially interesting is that the acquirers themselves are very different in character and strategy. For example,

Palo Alto Networks has built a reputation for acquiring market leaders and is willing to pay premium prices to get them. Their strategy is bold, aggressive, and focused on commanding entire categories.

Fortinet, in contrast, has learned how to expand its capabilities without overpaying. The company often acquires companies that struggled to break through on their own.

Cloudflare takes yet another approach: they prioritize buying brilliant, driven, and hungry teams, often alongside great technology, even if the businesses themselves weren’t commercially successful. In many ways, they are buying talent and innovation capacity as much as product.

All this is to say that while the trajectory of cyber consolidation is no different than what happened in other industries, the playbooks of today’s giants are pretty distinct, and everyone is approaching things in a different way, seeing value in different assets.

This finally brings us to the main point of this post: the illustration of the 20 years of cybersecurity consolidation. Here it is.

Here’s the higher-quality PDF for anyone interested in taking a closer look: 20 years of cybersecurity consolidation.

There’s a lot that could be said about each of these consolidation clusters, so much, in fact, that each company’s chart could easily be its own article. For now, I’ll leave it to you to draw your own conclusions, because this image is worth a thousand words. What’s undeniable is this: in just two decades, more than 200 companies have effectively consolidated into 11 dominant players.

The “200” figure is conservative because it only includes the companies I found, and counting the full number is impossible. Most of the companies you see represent full company acquisitions, but there are plenty of other deals that never made headlines. Most of the 11 giants have done at least one acquisition that never made the news, be it buying IP assets from a failed startup, adding talent through quiet acqui-hires, etc.

Palo Alto Networks: the most visible force in the security industry consolidation

Palo Alto Networks under CEO Nikesh Arora will go down in history as the company that has most certainly played a critical role in accelerating cybersecurity’s great consolidation. Today’s Palo Alto is an amalgamation of 37 (!) different companies, and that doesn’t even count the quiet deals. Beyond the headline acquisitions, Palo Alto has scooped up intellectual property, customer bases, and engineering teams in transactions that never made it into press releases. Some of these were “acqui‑hires” or IP transfers from startups that couldn’t make it on their own, and others, like its acquisition of assets from IBM, were big enough to become public. What makes Palo Alto play especially interesting is that the company has mastered the playbook of buying, absorbing & integrating security solutions into their core offerings.

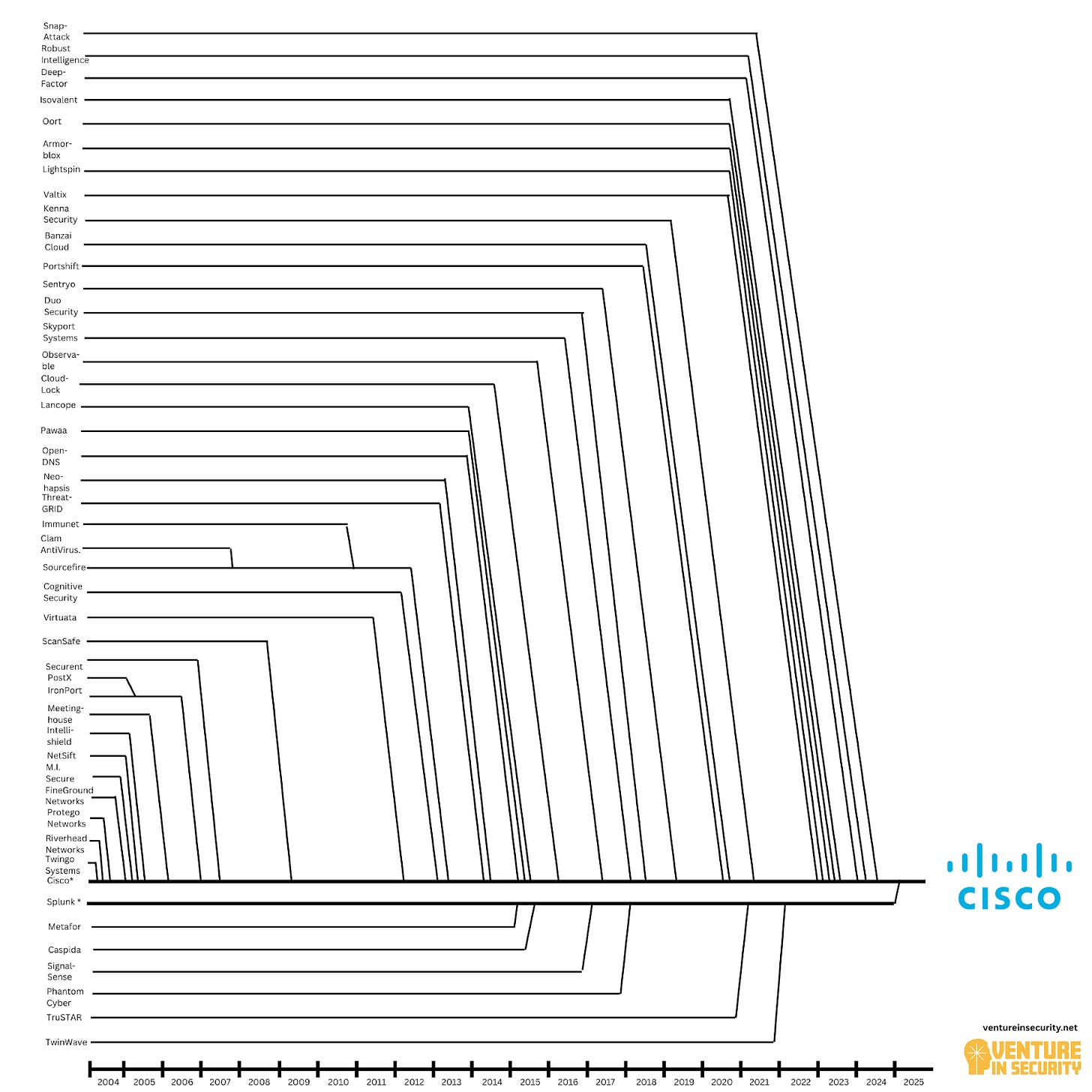

Cisco: the most impactful force in the security industry consolidation

If you asked most people in security who the biggest acquirer of cybersecurity companies is, the answer would almost certainly be Palo Alto Networks. That makes sense since the company has been pushing the consolidation narrative (or, as they call it, “platformization”) harder than anyone else, and we’ve seen they have brought together over 30 players. However, while Palo Alto may be the most visible acquirer, it’s not the biggest. That title belongs to Cisco, which has absorbed more than 40 (!) security companies over the past two decades. Cisco’s playbook differs from Palo Alto’s: instead of integrating acquisitions into a single platform, Cisco often allows them to continue as standalone business units.

Closing thoughts

If you were expecting that this article would end with some game‑changing conclusion or advice, I’m here to disappoint you: I don’t have either. What I’ve laid out is simply an outline of how I see we have gotten where we are, and how things will develop moving forward.

I often say that predictions about the future age poorly, but I’m confident this one won’t. Cyber isn’t all that unique, so like every industry, it goes through phases. The HBR research may be more than twenty years old, but it is as relevant today as it was when it was originally published. If you want proof, I suggest going over this chart from the original research and thinking about how it has changed over the past two decades (spoiler alert, all the industries have advanced at least one stage, and many more than one). I think cyber today fits somewhere between where Rubber & Tire Producers and Aircraft OEMs were two decades ago.

Cybersecurity has entered a decade of consolidation and messiness before it ultimately lands in the hands of a few giants. Companies like Palo Alto, CrowdStrike, Fortinet, Microsoft, Cisco, and Google know this. That’s why they’re spending billions to acquire the best technology and talent available, racing to secure their place at the top.

As with any seismic shift, there will be winners and losers. On one hand, it’s fair that CISOs want fewer tools (when you’re juggling 50 to 100 or more fragmented point products, the appeal of consolidation is undeniable). On the other hand, the freedom of choice they have today is unlikely to last. As the industry contracts to a small handful of dominant players, competition will shrink, and with it, so will the pressure to truly innovate. Most security people don’t fully grasp how fast this is happening, but then again, neither do most founders and VCs. The difference is that founders and VCs may stand to gain from the consolidation, at least in the short term. It’s also worth being clear that consolidation is a process independent of what people on LinkedIn or Reddit complain about. In this way, the future is predetermined.

The good news for startup founders and investors is that when the industry consolidates, the opportunity isn’t going to disappear. What will happen is that it’ll change shape. As cyber giants grow larger, and as founders depart (5 of 11 companies displayed here are still ran by their founders), they will naturally lose their ability to innovate, and they will have to keep buying new players. What will, however, change is the amounts they are willing to pay (that will decrease) and the number of acquisitions they’ll be making (that will also decrease). Think of it like a game of musical chairs: the music is still playing, but nobody knows when it will stop, or how many seats will be left when it does.