The tough business of incubating cyber innovation: a deep look at the cybersecurity-focused incubator and accelerator models

Analyzing the accelerator and incubator business models, breaking down the challenges, and recommending viable alternatives

Welcome to Venture in Security! Before we begin, do me a favor and make sure you hit the “Subscribe” button. Subscriptions let me know that you care and keep me motivated to write more. Thanks folks!

Introduction

A big chunk of cybersecurity, whether we like it or not, falls under the umbrella of deep tech - the area of technology where innovation is based on significant scientific and engineering advances. Naturally, not everything in the industry is deep tech: there are plenty of examples where technology is secondary to what the company is trying to achieve, and the originality comes from a different go-to-market strategy, customer segment, or similar. However, as we go into the future, we will be seeing more and more innovation in cybersecurity driven particularly by deep tech: AI, machine learning, quantum computing, and other emerging technologies.

Deep tech is known for high levels of risk and a long investment horizon because we cannot confidently predict when (and often - if) a specific technology will become usable, and most importantly - can be commercialized. Today, for example, nobody can say when the quantum revolution will happen, but we do know that when it finally does - it will break the internet and the foundations of technology and society as we know them. To prepare for the Q-day, we need to start working now, and for that, we need capital. Forecasting is a big part of investing in cybersecurity as the field is heavily impacted by technological advancements, government regulations, and the actions of adversaries. We don’t know how long it will take for standardization to happen in the IoT space, and neither can we predict when the new privacy laws will be articulated in different regions and countries, but the products we are designing today need to be flexible enough to respond to rapidly changing rules of the game.

The traditional venture capital model relies on the ability of the fund to exit (liquidate) all of its investments within a decade (granted, it’s not unusual to see 12-13 years old funds these days). Because VCs are investing somebody else’s capital and have specific return objectives, to reduce risks they have traditionally wanted to see some metrics showing that a startup looking for funding has some traction. The question is - how would one get to that traction when they are so early that all they have is a great idea and a few people passionate about solving a real-life problem? This is where startup incubators come in.

At times, I will be using the words “incubator” and “accelerator” interchangeably, but it is important to note that they are not the same. Incubators can provide support and resources for startups at different stages, but most commonly they focus on early-stage, pre-seed, and seed companies. The objective of accelerators, on the other hand, is to accelerate or supercharge learnings and growth, so they often look for startups that have shipped an MVP (minimum viable product) and saw some signs of the product-market fit. However, that’s not a requirement, hence many of the teams accepted to accelerators are still very early in the game. Startup incubators and accelerators are important players in the cybersecurity ecosystem. If we were to plot the risk levels against stages and types of industries, we’ll see that early-stage cybersecurity investing is the riskiest, and therefore the hardest:

This simple chart illustrates an important point: accelerators and incubators that support cybersecurity startups essentially take on more risk compared to angels, and much more compared to traditional VCs.

There are several cybersecurity incubators and accelerators across the globe; this chart shows some of the players. Up until recently, there was another one - CyLon based in London, UK, but it has recently pivoted away from the accelerator model (I will be talking about different models later).

Note that there is one type of incubators and accelerators I won’t cover in depth: those run by educational institutions. This is primarily because their motivations are often different (creating an ecosystem for student-driven innovation), and there may be complexities, such as questions around intellectual property ownership, that are too large to be effectively covered in this piece.

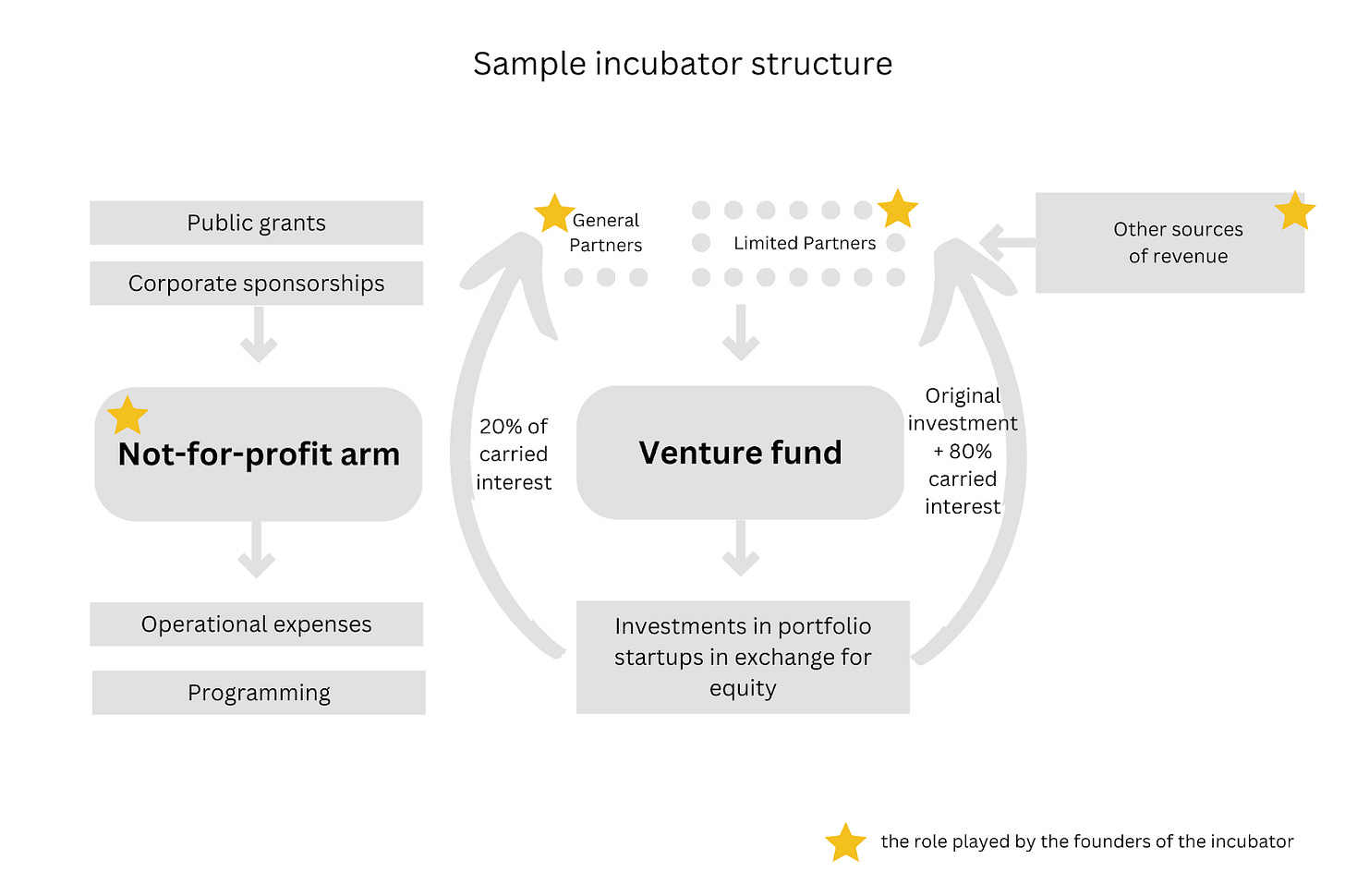

A disclaimer - graphs showing possible ways to structure an incubator are just illustrations and cannot be considered legal or tax advice. Different jurisdictions will have different views on a legal structure so consult with trusted professionals in your area if this is something you are interested in exploring.

Financial side of running a cybersecurity-focused accelerator: making the math work

If an accelerator or an incubator is run as an educational program with non-dilutive grants provided to select startups (essentially - free money), the math is relatively straightforward. It becomes much more complex when there is an investment component and an objective to generate profit. The discussion that follows assumes a more complex scenario.

Incubator and accelerator math

At first glance, it looks like it would make sense to have an accelerator be a part of an early-stage, pre-seed, or seed fund. However, when we look at the economics of accelerators closer, we realize that it’s hard to make the math work. To start, the traditional VC funding model does not work well for early-stage (pre-seed and seed) investing. It has become a standard in the industry for venture capital firms to adhere to the so-called “2 and 20” compensation structure: 2% of the fund size is the management fee the VC firm can use to cover its operational expenses (salaries, office, and so on), and 20% is the performance fee charged on the profits that the VC fund generates.

While there are some nuances in the way it’s calculated, what matters for our discussion is the 2% management fee a fund (or an incubator) could use for operations. Since pre-seed funds write small checks, the fund sizes tend to be small as well which has a direct impact on the amount of money that can be used to pay for day-to-day needs. A $10 million fund, as an example, would allow an incubator to use $200,000 per year (2%) for the first few years to cover its operational expenses - not a budget that would enable it to run active programming. This shows that the “2 and 20” funding model breaks pre-seed and seed investing unless the fund (on the accelerator) is much larger. Let’s look at a $100 million fund: at that size, assuming the same “2 and 20” structure, $2 million per year would likely be enough to cover operating expenses. However, with a $100 million fund, $50,000 or $200,000 checks are not possible - investors would need to make $4-5 million investments. Large ticket sizes are not suitable for pre-seed startups as it would be both too risky and a bad use of capital since investors would be providing much more money than a company at that stage can effectively use. Lastly, one cannot raise a $100 million fund without a solid track record, and can’t build that track record quickly by investing in pre-seed cyber (I will be talking about this catch-22 later).

The other problem with the accelerator model is that it's hard to design incentives that attract capital. Investors know that early-stage startups need money so they can attend a demo day or get introductions to the founder directly and find a way to invest. Startup accelerators can look for creative ways to incentivize investors to support their mission. For example, it could provide investors who become limited partners (LPs) in the accelerator with early access to companies in its portfolio, while also negotiating a more suitable accelerator compensation model (say, “10 and 20” instead of “2 and 20”). However, because the investors in venture funds have embraced the “2 and 20” compensation, the discussion may not go as smoothly, and the accelerator looking to run active programs would be forced to look for non-traditional funding sources.

Budgeting for enough “dry powder”

If an accelerator or an incubator is expected to generate financial returns, the math quickly becomes more complex as operational expenses are just a small part of the budget. The biggest part of the budget is the so-called “dry powder”, in other words - the amount of money an accelerator can invest in their startups. Since early-stage investing is risky, the accelerator would need enough capital to write small checks to a large number of startups. The more companies it invests in, the more likely it can achieve outsized returns (this principle is known in the venture world as the Power Law). What’s equally if not more important is having enough capital to double down on the small percentage of successes to prevent dilution and maintain the ownership as portfolio companies raise subsequent rounds. Since the valuation of the following rounds is typically higher, the fund would need to set aside enough capital.

Here is an example of how this math could work out assuming a $10 million fund.

Note that it assumes that the initial investment period resulting in 60 investments would be completed within four years (15 startups per year which is not easy but realistic). According to this example, after the first four years, the incubator would need to raise its second fund.

The unfortunate fact of incubator math is that no matter how much capital the firm has, it is typically unable to sustain pro-rata rights post-Series A as the valuations are significantly higher than when it initially invested.

Looking for funding sources

Whether an accelerator runs entirely as a not-for-profit, or if it has an investment component, it will need capital to operate. For those that do not have large (or any) funds under management, finding other funding sources is critical for survival. For those that do, the “2 and 20” model makes it hard (or impossible, depending on the market and other factors) to run programming, so finding other flows of capital becomes important as well. The two obvious sources are the government and the private sector.

Public funding

Public funding is an attractive source of capital as the government can provide money while asking for little in return: at best, it will want to see some basic KPIs about the performance of portfolio companies, but it is usually less than that.

The problem with initiatives funded by the government is the absence of clear goals as it is rarely driven by the desire to drive specific outcomes. Most publicly-funded initiatives do not last longer than the term of their sponsor. For a cybersecurity accelerator or an incubator at the pre-seed stage, this short-term approach is a death sentence: four or five years is not enough to make a lasting impact, and it is definitely not enough to prove the commercial viability of the model. Deep tech innovation takes years to commercialize, so even most successful companies typically won’t see an exit for 8-12 years. Unable to continue operating without public funding after the initial 4-5 years unless a new capital injection is secured, the vast majority of publicly-funded accelerators shut down or become ghosts - shadows of their former selves.

In the past decade, we have seen many accelerators and incubators emerge that rely exclusively on public funding, not just in the US, but in other countries as well. The government money can help to get the initiative off the ground, but it is not enough to grow it. Incubator founders seeing grants as the main funding source should continue looking for other investors as with public sources alone, they won’t be able to build an evergreen pre-seed fund. It’s worth noting that in some jurisdictions, the government may be less supportive of having the accelerator or incubator take equity in the companies it funds (although there are often ways to structure it in ways that make sense to them).

The irony of government-funded accelerators is that startups that come out of them will have as much struggle navigating the public procurement process as everybody else. While incubators and accelerators can often get companies in the private sector to look at their portfolio companies, public sector procurement is still based on RFPs (requests for proposals) and other bureaucratic processes. It would make sense that the government would be looking for ways to benefit from the innovation it helped to incubate, but that is not the case today.

Corporate sponsorships

For corporations, sponsoring startup incubators and accelerators can be a good way to top up their research and development (R&D) activities, learn about new innovations, and expand their networks by meeting other players of the ecosystem - thought leaders, companies, investors, and government officials.

A common value proposition startup accelerators sell to businesses is “brand awareness”. While that is certainly useful, the value typically diminishes after a year or two. Most importantly, many government-run accelerators and incubators offer the ability for companies to get their logo on the list of supporters at no cost, by sending a mentor or two, or by simply signing a letter of intent.

A decade ago, many companies were interested in getting exposure to innovative ideas and startups shaping the future of technology, and accelerators were seen as the place to find them. As time passed and corporations learned what they needed to learn, the incubator model has been largely demystified. Today, businesses that see value in working with early-stage startups tend to run their own accelerators or incubators; many are also establishing corporate venture funds (CVCs) to support companies within their area of interest. The CVCs typically invest in companies at series A and beyond, so they are not helpful for our discussion of early-stage innovation.

To get financial sponsorships from corporations, accelerators and incubators have to be creative in inventing and articulating their value proposition, and look for ways to make a long-lasting impact with the innovation coming from the accelerator. One example of such a value proposition could be around accelerating the community-led growth for companies pursuing it as a go-to-market strategy (often platforms and marketplaces).

Finding other sources of capital

Some startup accelerators might find ways to offer services enabling them to generate capital and fully fund their operations, or even to invest in their portfolio companies.

CyLon, for example, tried running an accelerator-as-a-service offering for governments and institutions all around the globe. Essentially, it productized the accelerator by creating educational modules, assembling them like lego blocks to fit customer requirements, and making partners a part of their process to find mentors, quickly establish connections across new ecosystems, etc. There is now a lot of competition in the accelerator-as-a-service space, but this illustrates the point that accelerators can find creative ways to generate additional operating and investment capital.

There are also examples of accelerators and incubators providing recruitment services, consulting, and looking for other ways to design business models aimed at offsetting some or all of the operating budget.

Having another source of investment capital could also enable the accelerator to become an LP in its own fund, meaning it can directly get equity in companies it supports. This would enable accelerator founders to potentially keep the whole investment return to themselves (not just the 20% carried interest or “carry”).

Ways to make the accelerator & incubator model work

VC-run incubators

If an established VC fund were to run a cybersecurity startup accelerator, it would likely be able to make the model work. By “established”, I mean both the size of the fund (as discussed above, it’s hard to make the accelerator math make sense with a $5-10 million fund), and the experience of the partners. Some of the factors increasing the likelihood of success are:

An established VC firm would typically already have someone responsible for supporting their portfolio companies, providing resources, making introductions, and so on (typically called platform). Running an accelerator could become a part of the platform function.

VCs would already have the real estate and salaries covered, making it easier to leverage their existing resources.

Venture capital firms have well-established expertise to select companies, active investor networks, and access to customers. Running an accelerator would give them a constant early-stage deal flow, something many larger investment firms often struggle with as with the growth of their funds, their focus shifts to writing large checks to later-stage ventures.

A VC firm considering running an accelerator would need to ensure it won’t harm its portfolio construction. An established VC would have likely made investments in startups across different segments, making it increasingly harder for them to find new companies that would not compete with the ones they’ve already invested in. This is even harder for pre-seed and seed investing as companies at this stage often pivot their ideas and business models, making yesterday's partners tomorrow’s competitors.

Lastly, it’s worth noting that a likely reason why we rarely see accelerators and incubators “attached” to a large VC is that the stage of investment is different (accelerators are often focused on pre-seed).

Venture studio

The venture studio model is much more hands-on and is different from an accelerator or an incubator in that it focuses on building a few companies instead of making bets on many. In this model, people running the venture studio find and validate ideas, size the opportunity and assess what it will take to succeed. If the business model, the risks, and the economics make sense, they hire founders - people who will be working on turning the idea into reality. Founders get paid a salary that is sufficient to cover their basic expenses and receive a meaningful portion of equity so that they are well motivated to make the startup a success.

To make the economics of this model work, the venture studio needs to take a bigger chunk of the cap table early in the company’s lifecycle. The higher portion of equity comes at the expense of cash flow, which in practical terms means that entrepreneurs running a venture studio need access to capital.

In the venture studio model, those running the studio act like co-founders rather than passive investors, especially at the early stages, providing hands-on support around product development, sales, roadmapping, recruitment, and so on. For a first-time founder capable of taking an idea and running with it this can be a great way to get started.

Not all venture studios are created equal, and some that take unreasonably large amounts of equity can cause problems for their own company’s future and its ability to raise capital. When the startup is going for a seed round, and founders already only own 20-30% of the company, it is clear that their motivation for making it a success is not going to be as high.

Venture studios are appropriate for mature, sophisticated ecosystems with well-developed talent such as Washington, DC in the US and Tel Aviv in Israel. In an immature ecosystem, building a venture studio focused on cybersecurity would not be a good idea.

A combination of the two (the DataTribe & Team8 model)

DataTribe, a foundry based in Maryland, is a rather unique example of a cybersecurity-focused accelerator that combines the elements of both models. DataTribe was founded by Bob Ackerman and Mike Janke, and backed by AllegisCyber, a VC firm also run by Bob. As a venture studio, DataTribe starts about three startups per year, and to date, it has incubated 18 cybersecurity companies.

Here is an excerpt from DataTribe’s website that communicates what they offer:

“DataTribe provides up to $2M at seed and follow-on investment capital at A to IPO rounds — significantly more than traditional investors, incubators, or accelerator programs. Our co-build model provides the runway and human resources you need to focus on launching a world-class company.

DataTribe works to educate each incoming startup team on the basics of getting a company up-and-running. From term sheet 101, to making the first sale.

DataTribe companies are provided with free office space for the entire team. Working with us gives you perks and discounts on high-tech services like AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud.

DataTribe companies get free or discounted access to essential business support services like legal and compliance, accounting, HR support, marketing, branding, and design.

DataTribe company founders work side-by-side with your team, and are co-located in our Fulton, MD headquarters for 12-18 months, until they raise a Series A.

A great product is more than great technology. Companies have unrestricted access to in-house product management and marketing experts to help shape the technology into a marketable product with lasting impact in the commercial world.

We co-build and launch a handful of companies a year, so if you succeed, we succeed. Our team works with you to design a company roadmap outlining key milestones and a path to get there.

Every DataTribe company has a personalized support team. DataTribe staff can embed with your team to fill key management and technical roles, attend pitches, sales meetings, and events, and tap into established professional networks on your behalf”.

Essentially, instead of giving capital and access to mentors to 10-30 companies with the hope that “something will happen”, DataTribe picks a few teams with high potential and provides them with all the support and hands-on help they need to grow. Since DataTribe is closely connected to AllegicCyber, the VC firm has the ability to invest in the startups from the cohort if it chooses to. DataTribe, therefore, combines the best of two worlds - a VC-run accelerator and a venture studio.

Another example of a cybersecurity venture studio that uses a similar model is Team8 based in Israel. Both studios illustrate the point that a mature cybersecurity ecosystem with access to talent, combined with great networks (Team8 and DataTribe have established phenomenal connections in the industry), can result in successful businesses.

Clarifying the value proposition

With the number of startup accelerators continuously increasing, and the competition for the best founders going up, ecosystem players looking to survive will need to be clear about their value proposition. New startup incubators and accelerators might be able to differentiate based on their programming - if they don’t have a track record supporting winners yet, they can invest in developing very comprehensive, relevant programs.

If the founders of the accelerator have a great industry network, they could try helping startups to build connections with early adopter customers. If they choose to double down on customer expansion as the main value-add, they will need to focus on continuously cultivating the list of CISO supporters. A CISO has a limited number of projects he or she can do in a given year as they are busy and underfunded. The accelerator would need to have tens of security leaders in their network willing to hopefully try a new tool every second or third year. Additionally, the accelerator would have to be located in a place with the highest concentration of CISOs - say, New York or Washington, DC. This model could work, but it would need to be heavily focused on business development.

Many accelerators and incubators make a strategic decision to embrace a “spray and pray” approach, bringing founders and mentors together and hoping that simply because of the number of interactions, something will come out of it. While that is certainly one of many ways to do it, it is too reliant on serendipity and therefore isn’t an ideal strategy for an accelerator.

A note on using accelerators and incubators to build a track record before raising a fund

It’s common to see entrepreneurs starting an accelerator to build a track record so that they can later raise a VC fund. While in theory, it is possible, several critical challenges can potentially inhibit the success of this idea.

At the core, it’s a catch-22 problem: it’s nearly impossible to raise the first fund without a track record, and it’s equally hard to quickly build a track record on pre-seed investing. It can take 8-12 years to get the first material exit, and few institutional LPs will put in the money after seeing early KPIs. Essentially, one needs to have enough capital to keep the incubator programs running for nearly a decade with no solid proof that it works.

Additionally, if the accelerator writes checks that are too small, and invests without a solid process, as a typical angel would, the track record it builds might not satisfy what limited partners, particularly institutional LPs such as endowments and funds of funds, are looking to see. Most accelerators do not have capital reserved for follow-on investments; this is one of the key differences to the VC model, and also a reason why their investment typically dilutes significantly by the later rounds. This prevents accelerators from being able to double down on winners, thus also significantly reducing their potential return multiples.

Cyber-focused accelerators: founder angle

Value-add of domain-focused accelerators

Startup accelerators and incubators are shortcuts that help founders learn and move much quicker than they would on their own. This is not to say that founders should always be looking to join one: if they are confident and experienced operators with all the necessary skills to build a company, or if they have just left a unicorn startup where they played an active role in growing it from the ground up - they can likely build a business on their own. Additionally, good VC funds have platform teams capable of providing support to their portfolio companies. That is to say that if you are a founder with an impressive pedigree in a hot space or a serial entrepreneur, you are likely better off just getting started on your own.

For first-time founders and those who haven’t yet had the chance to scale a company from a few people to millions in ARR, startup accelerators and incubators can make a huge difference. This is especially the case in cybersecurity. In many industries, a winning team looks as follows: someone who knows how to build the business working with someone who can build a technical product. In cyber, you need a third component - deep domain expertise, and it is not often that an early-stage startup would have all three. Security professionals, with rare exceptions, are not software developers, so the winning team for a cybersecurity startup is often a security expert plus a software engineer. That leaves a gap in business knowledge.

Even when all the ideal ingredients are in place, cybersecurity-focused accelerators and incubators can still make an impact. Cybersecurity is a nuanced space, and those without a deep understanding of these nuances typically find it hard to navigate the industry. Building products in security requires founders and product teams to design their solutions while considering the new threats that may emerge six months from the time they release an MVP. Recruitment requires one to remember the talent shortage and the need to grow the talent internally while recognizing that the threat landscape is going to evolve, and with that - the skills people need to develop to be successful. Marketing in cybersecurity has a unique flavor as purchasing decisions are based on trust which takes a long time to build, and stakeholder groups that hold power in security (such as industry analysts) are not nearly as impactful in other fields. Even the way storytelling works in security is different from other industries, as there is always a big educational component to it: you can’t sell security without educating your customer about the need to buy your product. Cybersecurity needs are still not market knowledge the way it works in most other industries. The list can go on and on, but the point I am trying to make is simple: generic startup accelerators and incubators lack an understanding of the nuances of cybersecurity.

Startup accelerators and incubators help founders expand their networks in a short period of time, meeting potential customers, security leaders, technical partners, and other founders. For an early-stage venture, being able to get an introduction to tens of CISOs can be a game changer: a conversation that starts from the angle of “a founder looking to learn” is typically much more productive compared to those that have an angle of “a founder looking to sell”.

On the flip side, accelerators and incubators not focused on specific domains tend to view the world in simpler and broader ways, and the fact that they don’t know all the nuances of cybersecurity can open new perspectives and bring new ideas to the table.

Reasons against participating in accelerators and incubators

There are two reasons one might decide to not join an accelerator or an incubator, and both have to do with the investment component of accelerator and incubator programs.

First, some VCs don’t like seeing accelerators on the cap table. While for most VCs, so long as the accelerator takes a fair amount of equity for their investment, having it as one of the early supporters is fine, others feel differently. This is because as the company grows, ideally any early-stage investor such as an angel or an incubator would either scale up with the company (continue providing capital & adding value) or cash out (exit). Accelerators tend to stay on the cap table on a perpetual basis, without putting in more money, or helping the company grow. If an accelerator is linked to the university network, it can become even more complicated as a part of the company’s intellectual property may be linked to the university - a situation no VC wants to find themselves in.

The other potential challenge is the so-called signaling risk which happens when a startup cannot raise capital at the demo day - typically the last event of the program where incubators invite investors from their network - angels, VCs, and solo GPs, to get early access to their portfolio companies. Demo days give founders the opportunity to create FOMO (fear of missing out). Not raising money 2-3 months after the demo day is considered a red flag, and if a company doesn’t get funding 5-6 months after graduation, it is very unlikely to pull it off at all.

The problem of “serial accelerator participation”

In the past decade, as we have seen the popularization of startups, it became common for founders to jump from one accelerator to another. On one hand, this behavior is easy to understand: each program can provide them with some small funding, a mentorship network, introductions to potential customers, and so on. The challenge is that most programs look similar, so the incremental value of joining yet another program is often minimal.

While joining a startup incubator or accelerator can give founders valuable resources and support, the perceived safety net is not real: to succeed, they still need to hustle, find customers, and do the leg work. Learning and networking are useful, but they alone will not help the business grow. Moving from one accelerator to another can feel like progress, but all it is doing is taking away the time and attention from pursuing the goals that matter.

Closing thoughts

Startup accelerators and incubators play an important role in the ecosystem. At their core, they pursue two distinct goals: building companies for success, and building founders for success. Even when companies they support do not become unicorns, it’s common to see founders take the experiences and learnings they’ve accumulated to try again, starting something else. The best accelerators help companies to grow faster and fail faster than they otherwise would.

The accelerator and incubator landscape is rapidly evolving. In the past decade, more and more people started to learn about entrepreneurship early in their lives, at school and in college business clubs. Large companies have realized the need for innovation as well, which resulted in the emergence of innovation labs, increased investment in R&D, and startup acquisitions.

VC funds are going in earlier: while initially accelerators and incubators emerged to close the funding gap created because established VCs would only invest at later stages, now big funds like Sequoia and Accel are growing their scout programs, and many others are raising seed and pre-seed funds or partnering up with solo GPs. Add to the mix a growing number of angel syndicates democratized by AngelList and alike, and it is no surprise that finding promising startups is becoming harder. Founders also have more options - there are industry-focused incubators, programs such as Hyper and Pyoneer, as well as new models like Entrepreneur First and Antler which bring aspiring entrepreneurs together, help them come up with an idea, and start a business from the ground zero.

In the next decade, as more and more data is moving online and every device becomes connected to the internet, cybersecurity will be even more critical to our ability to function as a society. Accelerators and incubators supporting security innovation have an important role to play. Those looking to stay long-term will have to reinvent their positioning, value proposition, and most critically - their business models. Incubators will need to have access to capital, or otherwise, they won’t be able to leverage their sole advantage - coming early and looking at a large pool of companies.

When run well, cybersecurity accelerators can be game-changers. Take the US-based MACH37 as an example. Funded in the first four years of its existence by Economic Development and the Commonwealth of Virginia, it made a lasting impact on the cybersecurity ecosystem in DC and the US at large. When MACH37 started, the investor community in DC was at the early stages of formation, and funding technology products wasn’t yet seen as a path to sizable returns. Local investors knew how to invest in services businesses such as government contractors, but there were not enough angels with the capital intensity for building software products. MACH37 not only needed to mobilize technical talent and find entrepreneurial founders, but it also had to bring together the investor community. Rick Gordon, at the time the Managing Partner of MACH37, was reaching out to investors from and outside of his network based all over the US - New York, Boston, Baltimore, and even Palo Alto. Around the same time, a local angel community emerged in DC with players such as Blu Venture Investors.

The challenge of proving that the accelerator model in cybersecurity works is real. MACH37 went through many changes over the years. It is still around, although it has undergone a number of changes, including the change in ownership and the leadership team, and has greatly reduced its programming. In the past, MACH37 has been incredibly successful, having incubated multiple companies that are now leaders in their segments, such as Huntress, but it remains to be seen where it will go from here. CyLon, formerly the leading UK-based cybersecurity accelerator with a pan-European focus, has now pivoted away from the incubator model into what appears to be a professionalized angel syndicate. Instead of trying to raise a fund and focusing on providing support to many startups, CyLon now invests its own capital and writes larger checks to a smaller pool of companies. They add value by bringing connections, customer and investor introductions, and a wealth of industry and ecosystem experience to the table, but they are no longer an accelerator. In general, making the accelerator business model work is not an easy task; while some models are better than others (a case in point is venture studios), there are factors beyond the accelerator’s control such as the presence of talent in the ecosystem which also heavily affect their success rates.

Resilience within cyberspace is a matter of national security so the government has to see it as a priority, and with that - change its approach to funding innovation. We have seen that it can do it, and In-Q-Tel is a prime example. To support cybersecurity startups, the government could provide funding commitment to accelerators and incubators for 10 years or more as that’s how long it takes to prove the commercial viability of the model. Once successful (and I am confident it will be successful if run well), we will see private investors flowing into the space as well.

Acknowledgments

This article would not have been possible without the fantastic conversations I was able to have with Joanna Wlazlak, Head of Platform at Element Ventures, Rick Gordon, CEO of Tidal Cyber, founder and former Managing Partner of MACH37, Scott Handsaker, CEO of CyRise, and Sumit Bhatia, Director of Innovation and Policy at Rogers Cybersecure Catalyst. All opinions and conclusions are my own.